How Netflix defined a brand that helped it to build a great product, and vice-versa

Today, Netflix is recognized by the simple letter “N.”

Twenty

years ago, no one recognized the Netflix logo. But today, with more

than 100 million members, customers instantly identify the logo and

trust Netflix in a way that counts — with their credit cards. But it

wasn’t always that way. Remember when Netflix announced its plan to

split its streaming and DVD service with the launch of “Qwikster” in

2011? 800,000 customers cancelled Netflix that quarter.

I grew up

in marketing, switched over to product, and became interested in

branding after success building Sesame Street, Schoolhouse Rock, and

Madeline software. I signed well-established brands to long-term

relationships, then brought the brands to life within children’s

educational software.

When I joined Netflix as VP of Product in

2005, I wanted to do more. My goal was to help a young company establish

a world-class product and brand. As a product leader, my job was to

delight customers in hard-to-copy, margin-enhancing ways. Based on

experience, I viewed building a brand as one of the most important of

these “hard-to-copy” tactics.

By the time I joined Netflix, I had

a somewhat nuanced view of how marketing and product should work

together: marketing defines the brand and product brings the brand to

life by building a great product. Together, the two teams hope to create

a world-class brand and product.

Here’s my definition of a brand:

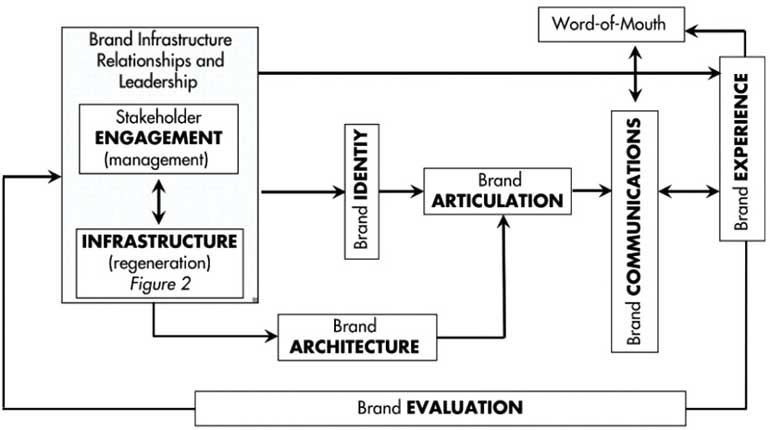

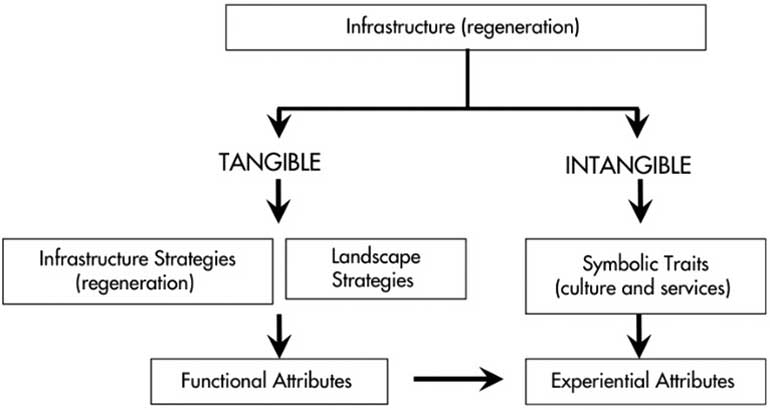

Below,

I outline two models to apply to your product or company, then show how

these models provided direction for the Netflix marketing and product

teams as the brand and product evolved:

1.) The positioning model

describes the first three components of the brand definition:

positioning, customer benefit, and personality.

2.) The brand pyramid adds the two remaining elements: aspiration and emotion.

3.)

The evolution of Netflix shows how the non-member homepage — the “store

window” of the site— evolved in tandem with the brand over twenty

years.

You’re

already an expert in positioning and don’t know it yet. Want proof?

What’s the first word that pops into your head when I mention the car

brand, “Volvo?” For most, the response is “safety.” This example

demonstrates Volvo’s ability to place an idea in your head, relative to

competitors, and that’s the definition of positioning.

To apply the first model, ask yourself three questions:

1.) In simple terms, how do you describe your product or company?

2.) How does it benefit customers?

3.) How do you define its personality? (The question behind the question: how do you want your product to relate to customers?)

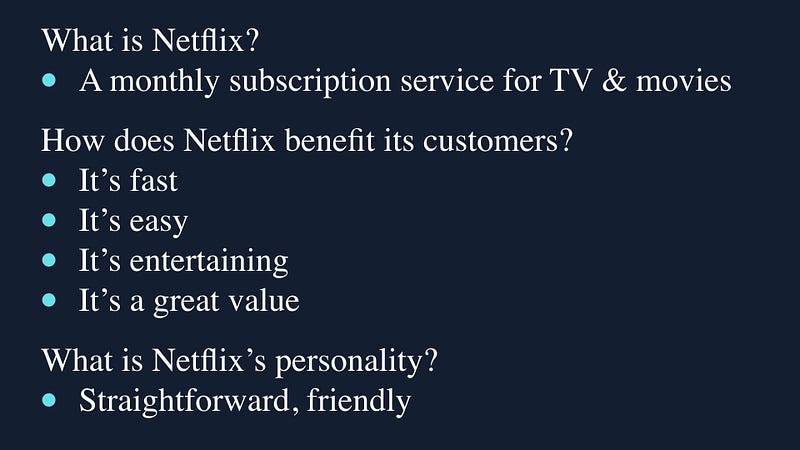

Here’s the model applied to Netflix:

Netflix Positioning Model

If you try this positioning model on your own, here are some tips:

Use clear, precise sixth-grade language. Consumers are busy and don’t have time to parse complicated ideas.

Be brief. Most teams begin with lots of complicated ideas. The key is to simplify and focus on a few, easy-to-communicate ideas.

In

answering the “personality” question, ask yourself, “If someone met my

company or product at a cocktail party, how would I like folks to

describe him or her?” Defining the personality of your product describes

how you want your brand to relate to customers.

Volvo is a

ninety-year-old company. They have spent billions of dollars on

advertising and have consistently invented new safety features to own

the word “safety.” Netflix is only twenty-years-old, but my guess is

decades from now the one word they will own is “entertainment.”

In the long-term, what’s the one word you’d like to own for your product or company?

This

framework builds on the positioning model and “ladders up” to define

emotional benefits for customers as well as the “something bigger” that

inspires your team. For this exercise, think long-term.

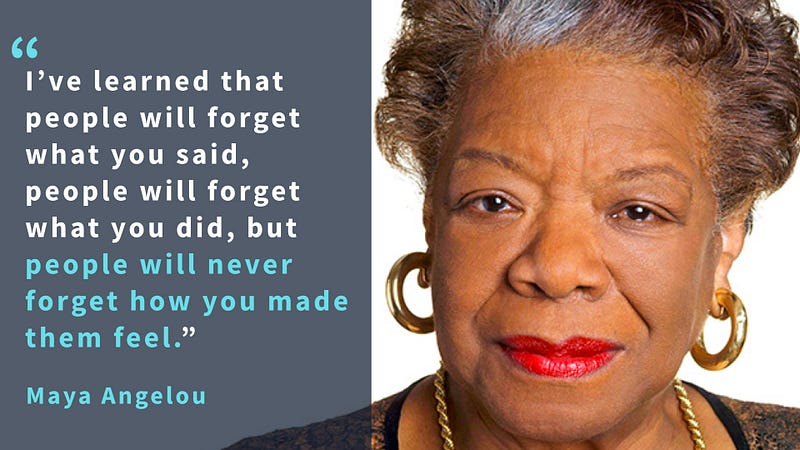

Why does

the brand model incorporate emotion? The simple answer: it makes things

memorable. Think for a moment about your childhood memories. My guess is

they all have emotional elements. The joy of a surprise birthday party?

The sorrow of losing a grandparent? Maya Angelou describes this

phenomenon best:

Acknowledging emotion in the brand framework helps make products memorable.

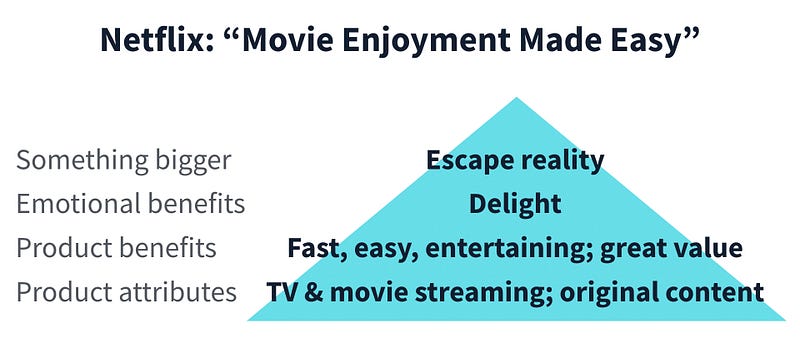

The

brand pyramid has four levels, and the intent is to read it from bottom

to top. The base contains product attributes or features and the other

elements ladder up from this foundation.

The Brand Pyramid

Below,

I explain each level of the pyramid along with advice on how to

approach the exercise on your own. Again, start at the bottom, with the

product attributes as the foundation.

Product attributes:

What are the product features that deliver benefits to customers?

Product benefits:

As

in the previous positioning model, how does your product improve

customers’ lives? (You can cut and paste your description of customer

benefits from the first positioning model.)

Emotional benefits:

How does your product make customers feel?

Something bigger:

In

the long-term, if you fully deliver the product and its emotional

benefits to your customers, how might your product dent the universe?

Think twenty years into the future.

Headline:

The headline

provides an executive summary of the model. In cases where you develop

an advertising campaign, it is the title of an ad campaign.

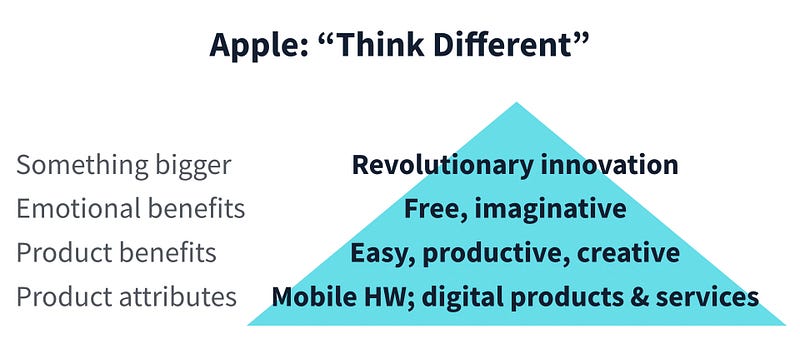

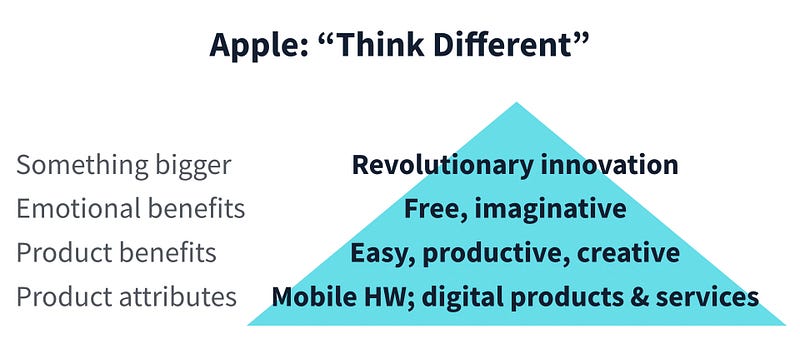

I’ll

illustrate the model first using Apple as I think it’s helpful to see

the pyramid in the context of a well-established brand:

Apple Brand Pyramid

For

Apple today, the product attributes — the “bits and bytes” of what they

deliver to us— are mobile hardware devices, along with the digital

products and services they provide on these devices.

The benefits

to customers are the ease of use of Apple’s human-centered design that

makes customers more productive and creative.

How does Apple make customers feel? We feel imaginative. We feel free.

Freedom and creative expression brought to life in Apple’s iPod ad

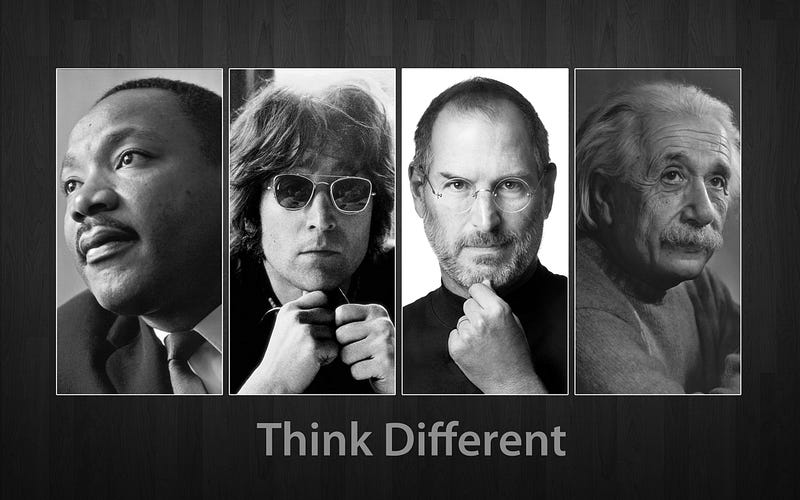

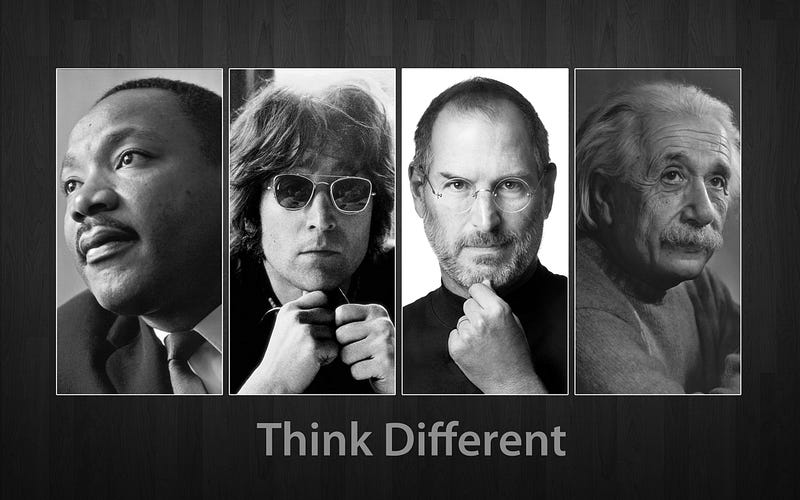

The

“something bigger” of Apple products? Think for a moment about the

Apple “Think Different” ad campaign, featuring Martin Luther King Jr,

John Lennon, Steve Jobs, and Albert Einstein. All four are

revolutionaries of their time. What is Apple’s “something bigger?”

It’s “Revolutionary Innovation.”

The Apple “Think Different” campaign, featuring four revolutionary leaders.

Consider

the power of the Apple brand. Would you pay a few hundred dollars more

for an electronic device that promises “revolutionary innovation?” Each

year, hundreds of millions of customers do. This premium illustrates the

economic power of a brand.

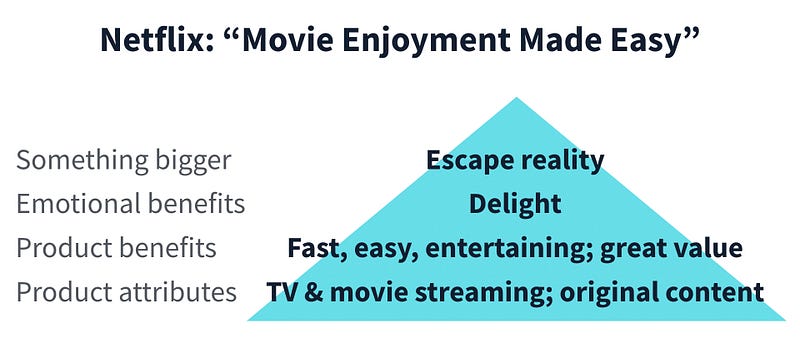

Here is the brand pyramid applied to Netflix:

Netflix Brand Pyramid

At

Netflix, Neve Savage was one of my marketing partners. I joke that he

tattooed, “Movie Enjoyment Made Easy” to my forearm so I wouldn’t forget

the phrase.

If you think back to the early days of Netflix, we

were a startup competing with Blockbuster, a retailer with 8,000 stores

and $8 billion in revenue.

But the Blockbuster experience sucked.

I

can remember walking to our neighborhood Blockbuster, wandering the

aisles, waiting in line to pay, then bringing a movie home to discover

that none of my family wanted to watch the movie. Even worse, I had to

pay late fees when I forgot to return the film.

Netflix’s early

DVD-by-mail service had an unlimited monthly subscription. The goal was

to delight our customers with lots of great movie choices, which arrived

the next day in the mail, and later, instantly via streaming.

The

“something bigger” was to deliver an entertainment experience that

transported you to the magical place movies can take you — to escape

reality. The intent was that the service would be so simple that the

technology and interface would fade into the background so customers

could immerse themselves in the movie.

Here are the tips I give to product and marketing teams as they apply the brand pyramid model:

Product

attributes. What are the features or components of your product that

consumers buy or use to enjoy the benefit of your product? In the early

days of Netflix, it was 100,000 movies on DVD, with one-day delivery, no

late fees, and a website where you built your queue. Today, it’s tens

of thousands of streaming movies & TV shows and, increasingly,

original content. Product attributes can and will change over time —

that’s where the innovation happens. The other levels of the pyramid,

however, stay relatively constant.

Product benefits. These are the

same benefits from the first positioning model. Just make sure that the

product attributes enable the product benefits.

Emotional benefits.

If you built a world-class product that delivers the benefits you

describe, but ultimately exceeds customers’ expectations, how would

customers feel? Make sure the words describe feelings.

Something

bigger. Many teams struggle with this part of the exercise. My coaching:

Think Big. Apple delivers revolutionary innovation, Nike enables

customers to fulfill their full human potential, and SpaceX is working

to save the human race by colonizing Mars. The “something bigger” is

meant to inspire your team to build a great product and company over

fifty years.

The headline. It took Apple tens of millions of dollars

to create their “Think Different” campaign. So don’t expect a few hours

of work to be as impactful. In the case of Netflix, “Movie Enjoyment

Made Easy” was not intended to be seen by customers, but the headline

summarized the brand pyramid in a way that I can still remember.

The

important thing is to take your best shot at defining the model, then

explore the various ideas with consumers via focus groups, surveys, but

most importantly, A/B tests.

For

years, Netflix marketing and product teams experimented with various

product features and how to best present them. As much as I have

described the positioning and branding models as static, this was not

the case. The positioning model was updated continuously. The upper

levels of the brand pyramid stayed more constant, however, providing

consistent direction for the product team.

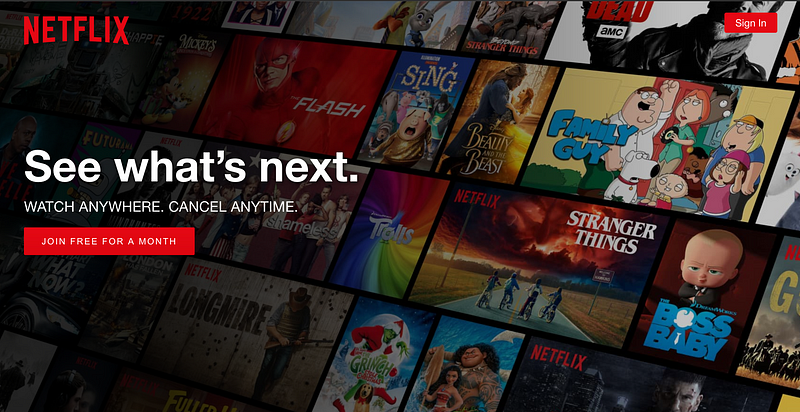

Netflix steadily

evolved the product — from DVDs by mail, to streaming, to original

content — and also tested the best ways to present the service to

customers. In some cases, we evaluated new ideas through exploration of

mock-ups and concept summaries. In other instances, we experimented with

how to present new features we had already developed. The product and

marketing teams worked together to continually innovate on both the

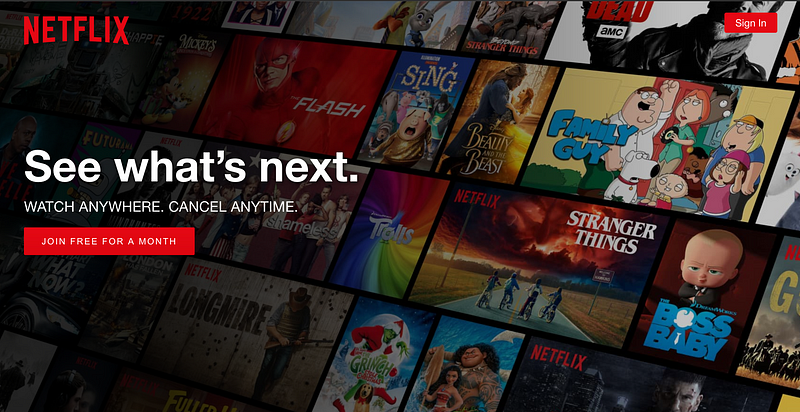

product and its presentation.

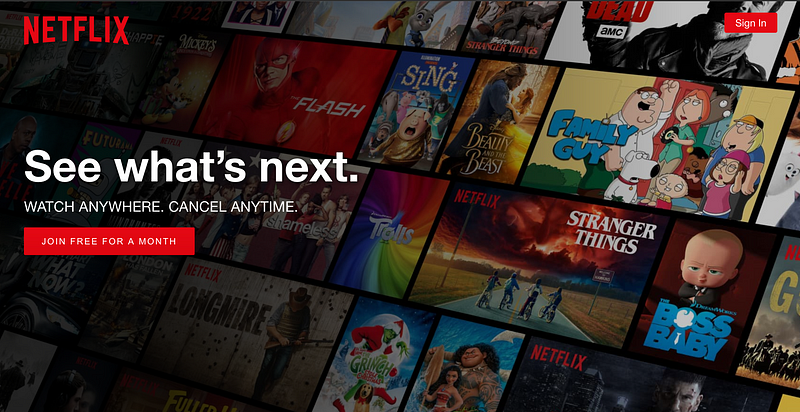

The Netflix non-member page today. Its job is to convert non-members who visit the site into a free trial.

While

many regard brand as amorphous and hard to measure, Netflix did its

best to measure its impact. We continually A/B tested different

positioning and branding approaches on the non-member homepage. We

focused on two key metrics:

1.) Trials/Visitors. Historically, 2% of visitors to the non-member site started a free trial.

2.) Conversion from free to paid membership. At the end of a free trial, about 90% of customers converted to paid membership.

A/B

testing enabled us to measure the efficacy of both our positioning and

brand. We tested new approaches every two weeks, and almost everything

you see on the non-member homepage is a proven winner.

Looking

back on my time at Netflix, I consider the work in this area to be the

result of a dance between marketing and product, judged by customers via

ongoing qualitative and quantitative research. Below I share nearly

twenty years of non-member page iteration. I think you’ll be surprised

by how much the positioning, brand, and product evolved.

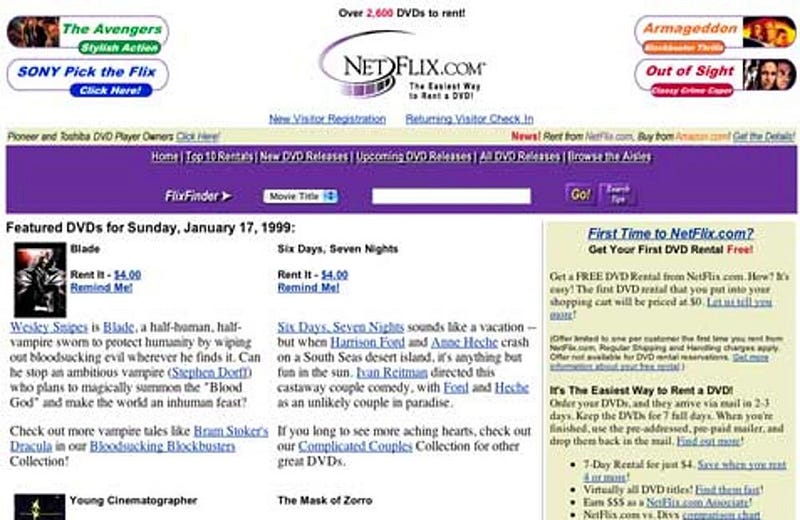

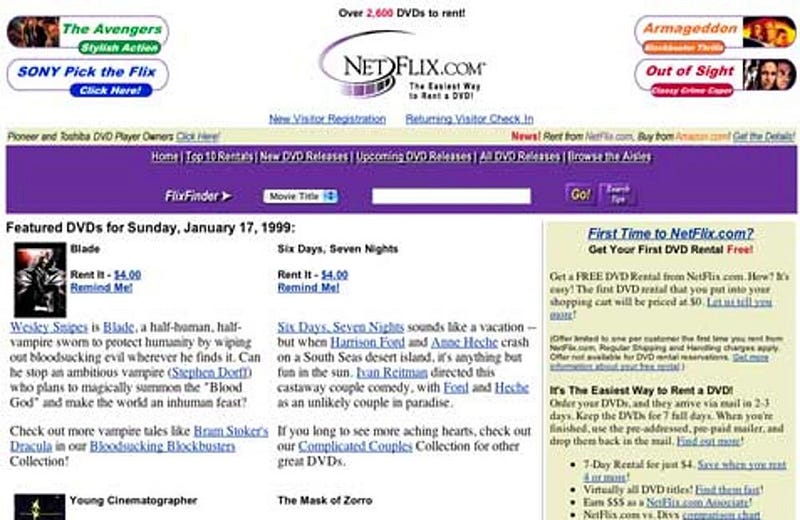

Netflix in 1999

In

1999, Netflix was an e-commerce site, focused on selling DVDs — only 1%

of its transactions were rentals. There were just 2,600 titles, and the

DVDs arrived 3–5 days after you ordered them. I like this page as it

reminds me that all startups suck in the beginning. It’s fun to look

back to see how far you’ve come.

At this point, Netflix made a

“bet the company” pivot to focus exclusively on DVD rental. The team

added the Queue and eliminated both due dates and late fees for their

fledgling DVD-by-mail rental program. They made this decision based on a

few focus groups and the correct assumption that Amazon would

eventually dominate DVD sales.

2004

In

2004, Netflix was an “all you can eat” DVD-by-mail subscription

service. With no due dates or late fees, the service was well-positioned

against Blockbuster, and the DVD library had grown to 35,000 titles.

The couple on the couch hint at the emotional benefit of “movie

enjoyment made easy.”

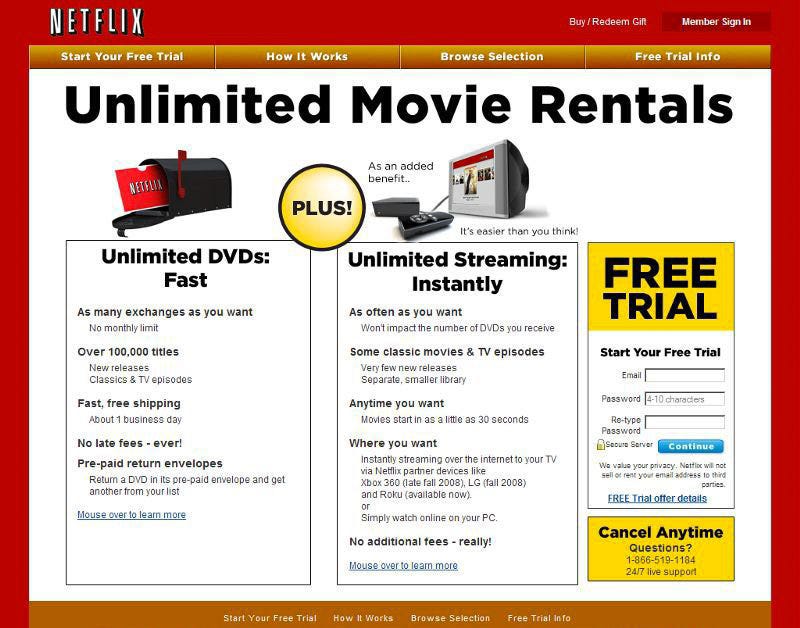

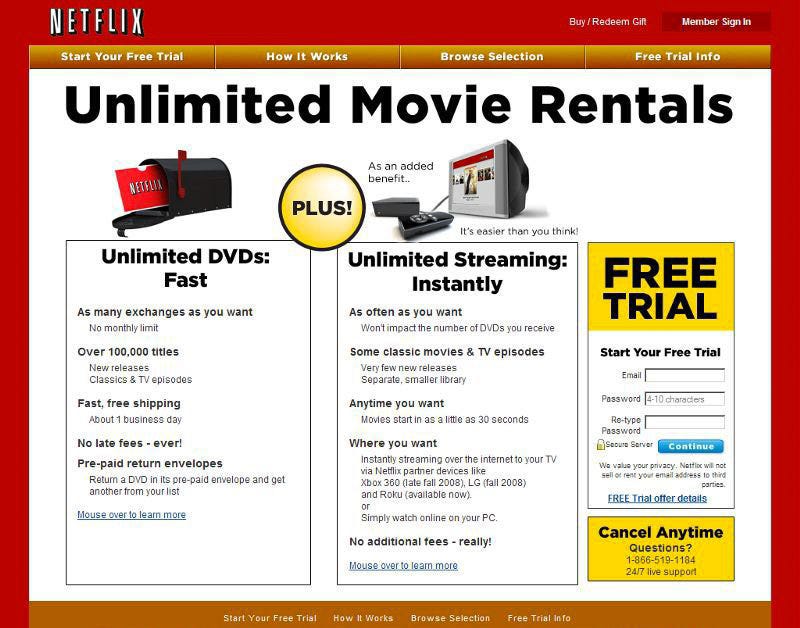

2008

By

2008, there’s constant testing on the non-member page as Netflix

explores how to combine its growing DVD-by-mail library with its nascent

streaming service.

The Roku launch in 2008 was the first step in

Netflix’s long-term strategy to create a hard-to-copy network effect by

giving all TV manufacturers the tools they needed to make their TVs

“Netflix Ready.” But in 2008, Roku was the only device that enabled

Netflix members to watch movies on their TV.

2009

In

2009, there was a clear, family-friendly positioning and the non-member

site is now simpler. But the homepage still positions streaming as a

minor “bonus” to its DVD-by-mail service.

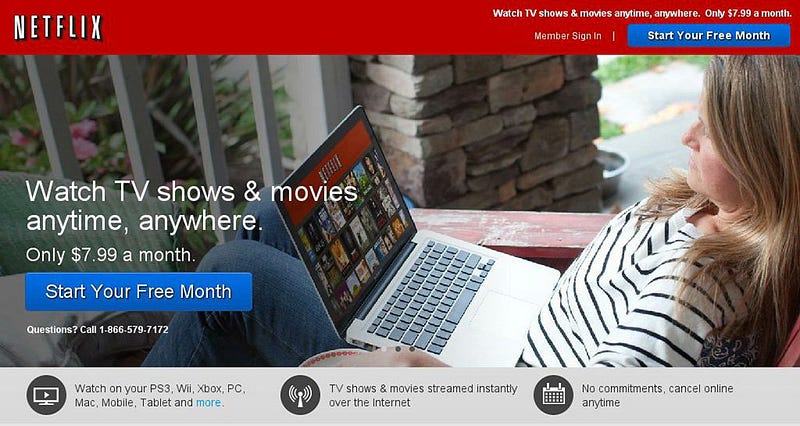

2010

By

2010, Netflix commits itself more fully to streaming, recognizing that

its huge DVD-by-mail library will have a diminishing competitive

advantage as the industry shifts from DVD to streaming. Netflix is now

“streaming first.”

2011

By

2011, Netflix presents its DVD-by-mail service as an “add-on” to its

streaming service — it has come full circle since 2007. The company is

now aggressive about promoting the ability to watch on TV, given the

service is now on all three major tv-based gaming platforms.

In

2011, Netflix was also experimenting with Facebook Connect as a means to

sign-up and get movie recommendations from friends. This social

approach eventually failed — twice. Customers weren’t interested in

sharing their movie tastes with friends, and when they did, their

friends thought they had terrible taste!

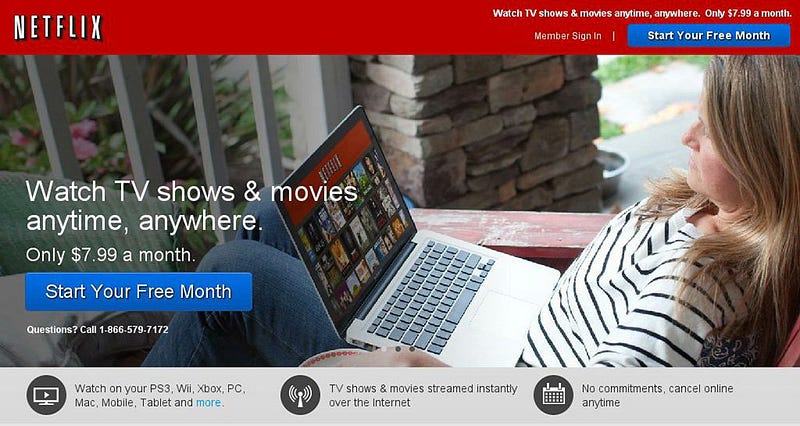

2012

Finally,

in 2012, the site gets simpler. Netflix now has more than 30M members,

and the brand now communicates real meaning to consumers. The site no

longer commits as much space to describing what it is and how it works.

The DVD-by-mail service still exists as an add-on, but there’s no

reference to it on the non-member homepage. Netflix is now a streaming

service.

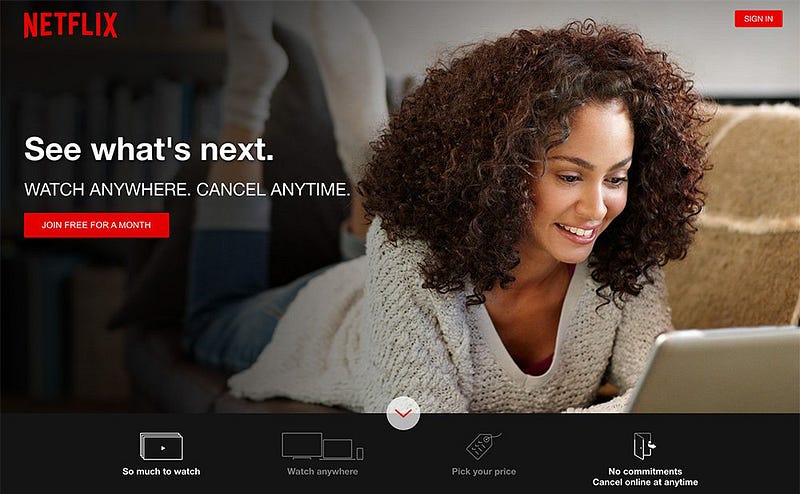

2013

The

non-member site is now substantially simpler. Simpler versions of the

site had been A/B tested for years, but more complicated versions

consistently won. It’s counterintuitive that the earlier, simpler

designs failed — simple typically trumps complete. But more “stuff” on

the screen was an efficient way to communicate value at the time. In

2013, the Netflix brand finally provided this value instead.

A

last note: 2013 is the year that Netflix launched its first original

series, “House of Cards,” so original content is now an attribute of the

company’s offering. At this point, Netflix began to invest its

marketing dollars in its original content — something they didn’t do

when they were an aggregator of other studios’ content.

2013

By

late 2013, there’s increasing focus on the ability to “watch anywhere”

as you can now watch on tablets, mobile devices, and hundreds of

“Netflix-Ready” TV-connected devices. There’s also a continued trend

towards a simpler, non-member experience.

2014

What

says “Movie Enjoyment Made Easy” more than a happy family on a couch?

Note that there’s no hardware or interface on the page. Netflix now lets

you fade into your couch with no technology or complexity to distract

you from your movie-watching experience.

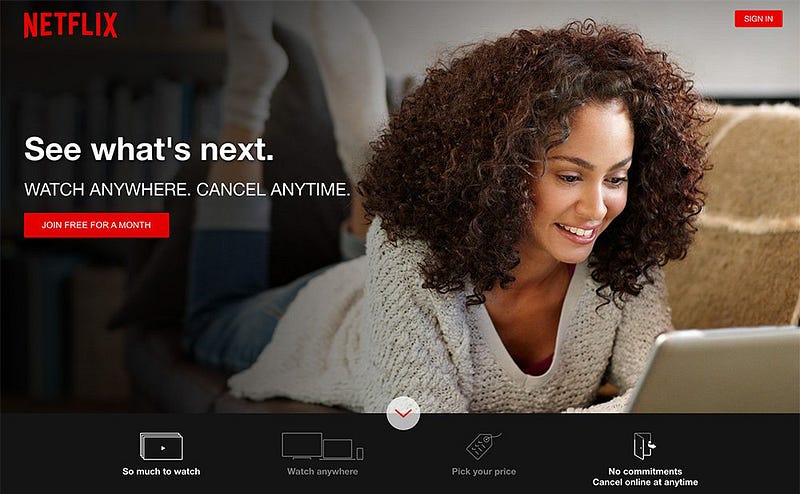

2016

She

looks delighted, right? Netflix is both well-known and trusted, so

there’s no real estate required to explain what the product is and the

free trial continues to be the best way to enable folks to enjoy the

experience. And for the reluctant “fence-sitters,” the ability to

“cancel anytime” reduces their perceived risk.

2017

Today,

the site focuses on movies with a hint of Netflix’s growing original

content library. (Note Season Two of “Stranger Things” at the center of

the screen.)

What will Netflix experiment with next? I’m sure

there are lots of hypotheses being tested right now. As in the past,

Netflix will continually experiment on its non-member site, both to

identify which potential ideas resonate with customers and to determine

how to position new features they have already built.

Conclusion

Over

the last twenty years, Netflix has evolved from a DVD e-commerce site

to a worldwide Internet TV company. The dance between product, marketing

and consumers continues as teams work to define and deliver both a

brand and a product that delight customers in hard-to-copy,

margin-enhancing ways. Today, Netflix is a world-class company with a

distinct advantage in its hard-to-copy brand.

I’ll leave you with

one final thought, highlighting the importance of teamwork between

marketing and product to enable product and brand innovation:

“Today,

brands are not the preserve of a marketing department. Brands are too

important to be left to the marketing department — or any other

‘department,’ come to that. Organizational ghettoes do not create

vibrant world-changing brands.” — Thomas Gad

|

| Rubén Weinsteiner |

Fewer

cite other considerations as major reasons why they identify with their

party. About half of Democrats (51%) and 45% of Republicans cite having

a lot in common with other members of their party as a major reason.

Fewer

cite other considerations as major reasons why they identify with their

party. About half of Democrats (51%) and 45% of Republicans cite having

a lot in common with other members of their party as a major reason.  For

independents who lean toward a party, the belief that the other party’s

policies are harmful is the most frequently cited reason for their

partisan leaning. Nearly six-in-ten Republican-leaning independents

(58%) and Democratic leaners (57%) say a major reason for leaning to the

Republican and Democratic parties, respectively, is a feeling that the

other party’s policies are harmful for the country.

For

independents who lean toward a party, the belief that the other party’s

policies are harmful is the most frequently cited reason for their

partisan leaning. Nearly six-in-ten Republican-leaning independents

(58%) and Democratic leaners (57%) say a major reason for leaning to the

Republican and Democratic parties, respectively, is a feeling that the

other party’s policies are harmful for the country.

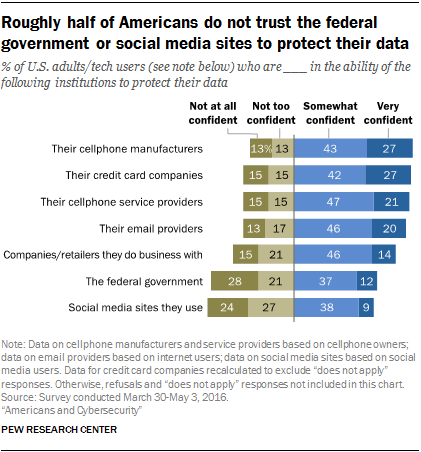

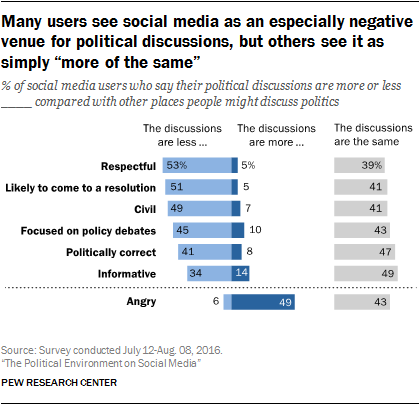

Another survey last year found that just 9% of social media users were “very confident” that social media companies would

Another survey last year found that just 9% of social media users were “very confident” that social media companies would  Moreover,

social media users can be turned off by what happens on social media.

For instance, social media sites are frequently cited as places where

Moreover,

social media users can be turned off by what happens on social media.

For instance, social media sites are frequently cited as places where

Today, Netflix is recognized by the simple letter “N.”

Today, Netflix is recognized by the simple letter “N.”

Netflix Positioning Model

Netflix Positioning Model

The Brand Pyramid

The Brand Pyramid Apple Brand Pyramid

Apple Brand Pyramid Freedom and creative expression brought to life in Apple’s iPod ad

Freedom and creative expression brought to life in Apple’s iPod ad The Apple “Think Different” campaign, featuring four revolutionary leaders.

The Apple “Think Different” campaign, featuring four revolutionary leaders. Netflix Brand Pyramid

Netflix Brand Pyramid

The Netflix non-member page today. Its job is to convert non-members who visit the site into a free trial.

The Netflix non-member page today. Its job is to convert non-members who visit the site into a free trial. Netflix in 1999

Netflix in 1999 2004

2004 2008

2008 2009

2009 2010

2010 2011

2011 2012

2012 2013

2013 2013

2013 2014

2014 2016

2016