Rubén Weinsteiner

Protesters

rally as part of a wave of worldwide protests against racism and police

brutality on Place de la Republique in Paris in June 2020. (Mehdi

Taamallah/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Protesters

rally as part of a wave of worldwide protests against racism and police

brutality on Place de la Republique in Paris in June 2020. (Mehdi

Taamallah/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

How we did this

This

MARCA POLITICA analysis focuses on attitudes toward diversity and

conflict around the world. For this report, we conducted nationally

representative surveys of 16,254 adults from March 12 to May 26, 2021,

in 16 advanced economies. All surveys were conducted over the phone with

adults in Canada, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the

Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Australia, Japan, New

Zealand, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan.

In the United

States, we surveyed 2,596 U.S. adults from Feb. 1 to 7, 2021. Everyone

who took part in the U.S. survey is a member of the Center’s American

Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through

national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all

adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be

representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity,

partisan affiliation, education and other categories.This study was

conducted in places where nationally representative telephone surveys

are feasible. Due to the coronavirus outbreak, face-to-face interviewing is not currently possible in many parts of the world.

To

account for the fact that some publics refer to the coronavirus

differently, in South Korea, the survey asked about the “Corona19

outbreak.” In Japan, the survey asked about the “novel coronavirus

outbreak.” In Greece, the survey asked about the “coronavirus pandemic.”

In Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Taiwan, the survey asked about

the “COVID-19 outbreak.” All other surveys used the term “coronavirus

outbreak.” Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses. See our methodology database for more information about the survey methods outside the U.S. For respondents in the U.S., read more about the ATP’s methodology.

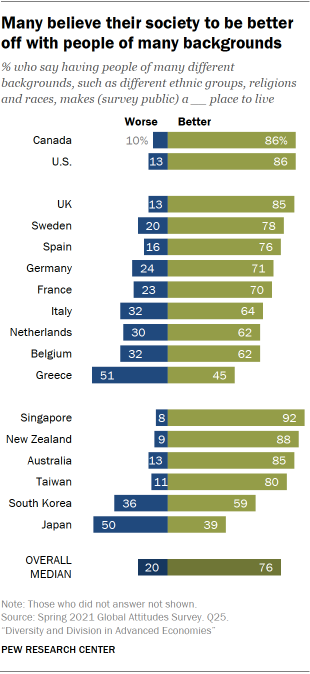

Wide

majorities in most of the 17 advanced economies surveyed by Pew

Research Center say having people of many different backgrounds improves

their society. Outside of Japan and Greece, around six-in-ten or more

hold this view, and in many places – including Singapore, New Zealand,

the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia and Taiwan – at

least eight-in-ten describe where they live as benefiting from people

of different ethnic groups, religions and races.

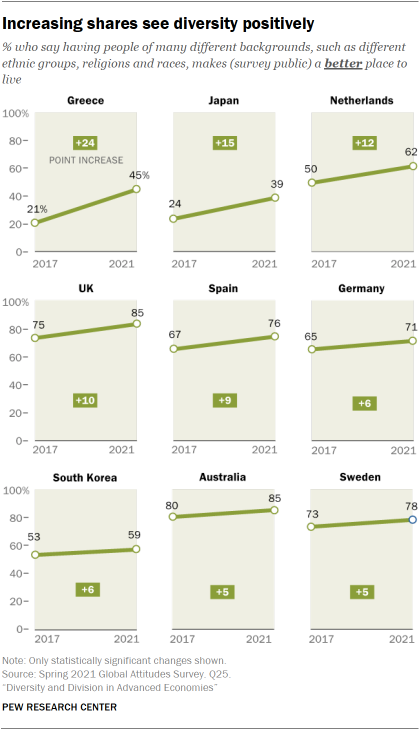

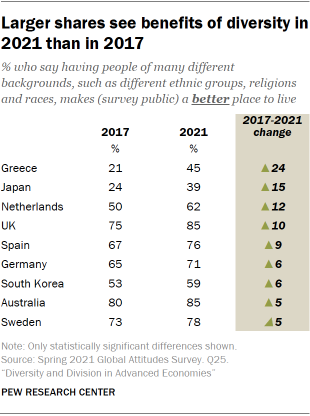

Even

in Japan and Greece, the share who think diversity makes their country

better has increased by double digits since the question was last asked

four years ago, and significant increases have also taken place in most

other nations where trends are available.

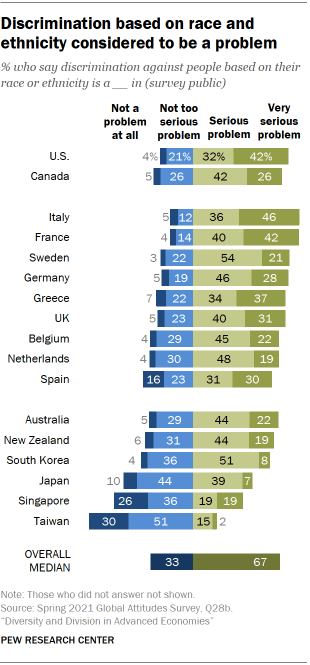

Alongside this growing

openness to diversity, however, is a recognition that societies may not

be living up to these ideals: In fact, most people say racial or ethnic

discrimination is a problem in their society. Half or more in almost

every place surveyed describe discrimination as at least a somewhat

serious problem – including around three-quarters or more who have this

view in Italy, France, Sweden, the U.S. and Germany. And, in eight

surveyed publics, at least half describe their society as one with

conflicts between people of different racial or ethnic groups. The U.S.

is the country with the largest share of the public saying there is

racial or ethnic conflict.

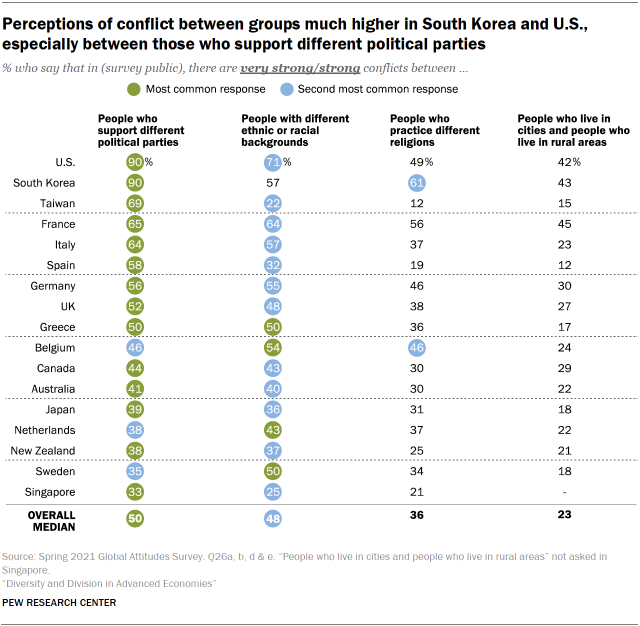

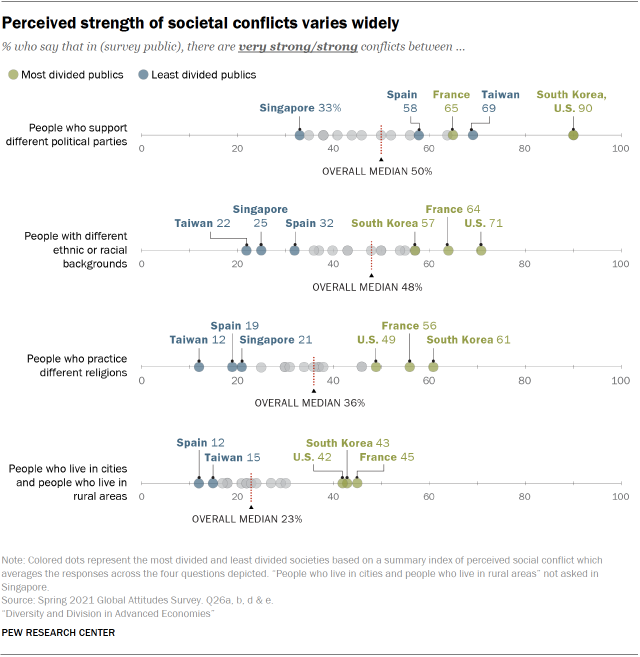

Notably,

however, in most societies racial and ethnic divisions are not seen as

the most salient cleavage. Rather, in the majority of places surveyed,

more people identify conflicts between people who support different

political parties than conflicts between people with different ethnic or

racial backgrounds. Political divisions are also seen as greater than

the other two dimensions tested: between those with different religions

and between urban and rural residents. (For more on the actual

composition of each public surveyed on each of these dimensions, see Appendix A.)

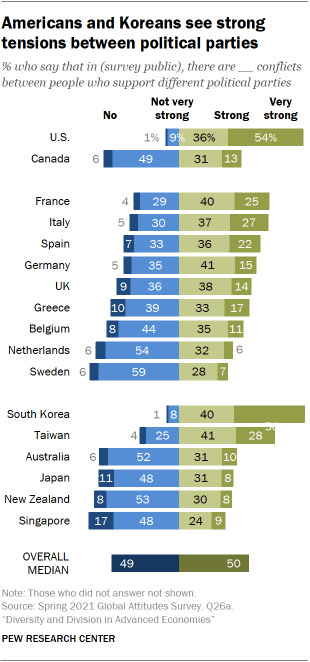

In

the U.S. and South Korea, 90% say there are at least strong conflicts

between those who support different parties – including around half or

more in each country who say these conflicts are very strong. In Taiwan,

France and Italy, around two-thirds say the political conflicts in

their society are strong. Still, in around half of the surveyed publics,

fewer than 50% say the same.

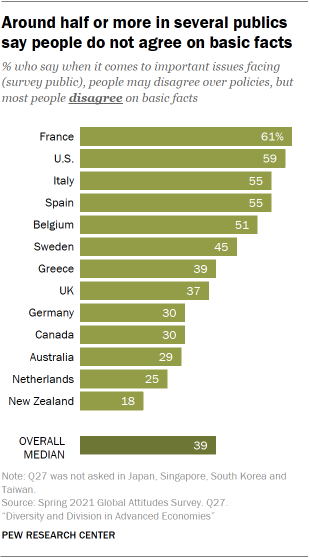

In

some places, this acrimony has risen to the level that people think

their fellow citizens no longer disagree simply over policies, but also

over basic facts. In France, the U.S., Italy, Spain and Belgium, half or

more think that most people in their country disagree on basic facts

more than they agree. Across most societies surveyed, those who see

conflict among partisans are more likely to say people disagree on the

basic facts than those who do not see such conflicts.

Views on

the topic are also closely related to views of the governing party or

parties in nearly every society (for more on how governing party is

defined, see Appendix B).

In every place but the U.S. and Italy, those with unfavorable views of

the governing coalition are more likely to say most people disagree on

the basic facts than those with favorable views of the government.

Although

divisions between racial and ethnic groups as well as between partisans

are palpable for many, other types of conflicts are less commonly

perceived. For example, in no place surveyed does a majority think there

are strong conflicts between people who live in cities and people who

live in rural areas. Similarly, only a minority in most countries say

there are divisions between people who practice different religions –

though around half or more do sense such conflicts in South Korea,

France and the U.S.

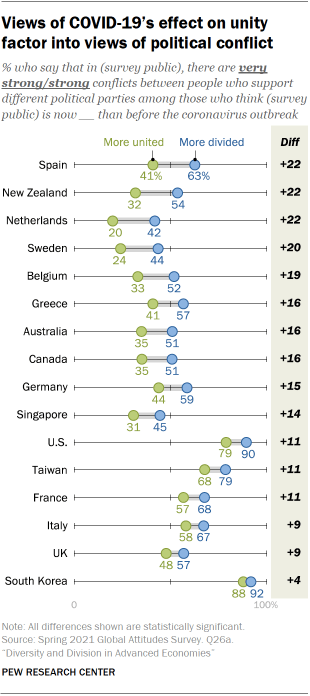

Beyond divisions between specific groups,

there is also a widespread – and growing – sense that societies are more

divided now than they were before the COVID-19 pandemic. A median of 61% across the 17 advanced economies

say they are now more divided than before the outbreak, and in all but

one of the 13 countries also polled in summer 2020, the sense that

societies are more divided than united has risen significantly since

last year. Those who describe their society as more divided than before

the global health emergency are also significantly more likely to see

conflicts between different groups in society and to say their fellow

citizens disagree over basic facts.

Spotlight: Divided societies

In

the U.S., France and South Korea, at least a majority say that having

people of many different backgrounds makes their country a better place

to live. Still, these three countries stand out for the degree to which

people perceive various conflicts. In each of these places, the publics

are among the most likely to describe their society as divided, and this

is the case across each of the dimensions asked about: political,

racial and ethnic, religious, and geographic.

United States

When

it comes to perceived political and ethnic conflicts, no public is more

divided than Americans: 90% say there are conflicts between people who

support different political parties and 71% say the same when it comes

to ethnic and racial groups. (Results of a different question

asking specifically about conflicts between Democrats and Republicans

also found that 71% of Americans think conflicts between the party

coalitions are very strong and another 20% say they are somewhat strong.

The sense of conflicts between Democrats and Republicans also increased

between 2012 and 2020.)

In terms of divisions between people

who practice different religions and between urban and rural residents,

again, Americans consistently rate as one of the three most divided

publics of the 17 surveyed.

Some of these perceived divisions

differ by racial and ethnic background. For example, more Black adults

(82%) see conflict between people with different ethnic or racial

backgrounds than White (69%) or Hispanic (70%) adults.

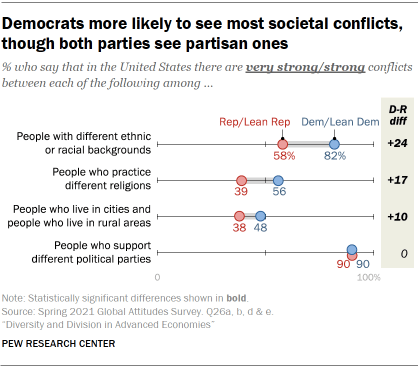

Another

major axis of division in the U.S. is partisan identification.

Democrats and independents who lean toward the Democratic Party are much

more likely to see conflict between people of different racial and

ethnic groups than are Republicans and independents who lean Republican.

There are also partisan differences in opinion over whether people who

practice different religions or those who live in urban and rural areas

have conflicts.

Notably, however, both Democrats and Republicans

share a widespread belief that there are conflicts between those who

support different political parties. Democrats and Republicans are also

equally likely to say Americans disagree over basic facts. For more, see

“Americans see stronger societal conflicts than people in other advanced economies.”

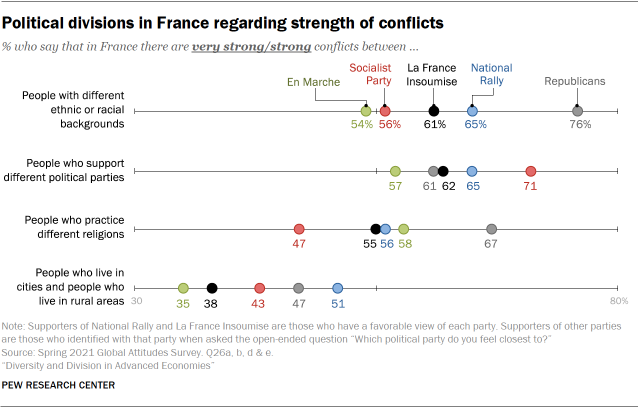

France

On

three of the four dimensions asked about, French adults are among the

most likely to say there are conflicts – and the highest share in France

perceives divisions between rural and urban residents. Partisanship

plays some role in perceived divisions. Supporters of the Republicans, a

right-of-center party, tend to see more conflicts than supporters of

the Socialist Party or the ruling En Marche. For example, 76% who

support the Republicans say there is conflict between people of

different racial or ethnic groups, compared with 56% of Socialist Party

supporters or 54% of En Marche supporters.1 French women are also more

likely to see conflicts in many parts of their society than are men.

South Korea

More

in South Korea than in any other public surveyed say there are

conflicts between people who practice different religions (61%) in their

society. They are also tied with the U.S. as the society where the

highest share sees partisan divisions: 90% of South Koreans say this,

including 50% who say such conflicts are very strong. And, on issues

between ethnic and racial groups and between rural and urban residents,

South Korea is consistently one of the top three most divided publics.

There

is no single pattern to the divisions that South Koreans perceive in

their society. Rather, depending on the conflict in question, different

cleavages emerge. For example, when it comes to conflicts between rural

and urban residents, those with lower incomes are more likely to

identify conflicts than those with higher incomes. Younger South

Koreans, for their part, are more likely to say there are racial or

ethnic conflicts in their society than are older people, and those with

higher education levels also agree relative to those with lower

education levels.

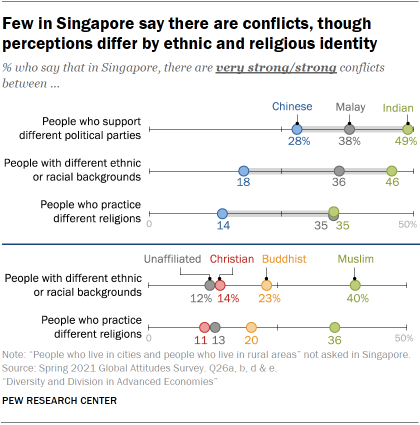

Spotlight: Societies with fewer divisions

Singapore

The small island nation of Singapore is one of the least divided societies surveyed. Although it is ethnically and racially diverse

– and even boasts four official languages that correspond with the

dominant ethnic groups – fewer Singaporeans (25%) report conflicts

between people of different ethnic and racial backgrounds than nearly

any other public surveyed. Singaporeans are also among the least divided

religiously, with only 21% saying there are conflicts between people

who practice different religions, despite being quite heterogeneous religiously.

Notably, however, perceived divisions vary based on people’s

self-reported ethnic and religious identity. For example, ethnic Indians

and Malays are more likely to see political, ethnic and religious

conflicts than ethnic Chinese. Similarly, Muslims are somewhat more

likely to see conflicts both between those who practice different

religions and those of different racial and ethnic groups than are

self-reported Buddhists or Christians.

Singapore also stands

out for seeing the fewest divisions between people who support different

political parties (33%). The nation-state is largely governed by the People’s Action Party,

which garnered around 61% of the vote and 89% of parliamentary seats in

the most recent 2020 election, with the Worker’s Party securing the

remainder. Singaporeans were not asked about conflicts between rural and

urban residents because the nation-state is entirely urban.

Spain

Spaniards

are the least divided among the 17 publics surveyed when it comes to

geography, with only 12% of the public saying there are conflicts

between rural and urban residents. Only 19% report conflicts among those

who practice different religions, making it one of the two least

religiously divided societies. And only around a third see conflicts

between those with different racial and ethnic backgrounds, which ranks

the country in the bottom three for this division as well. Still, when

it comes to partisan differences, Spaniards see more conflicts. This country – which has active separatist movements, and has seen the collapse of the two-party system and the rise of populist parties

– is one where a 58% majority see at least some conflict between those

who support different political parties. Spaniards on the ideological

left are somewhat more likely than those on the right to describe

conflicts between partisans.

Taiwan

The share of adults in

Taiwan who say there are conflicts between people who practice different

religions (12%) is smaller than the share who say the same in any of

the other places surveyed. They are also among the least likely to

report conflicts between rural and urban residents (15%) and between

those with different racial and ethnic backgrounds (22%). Still, adults

in Taiwan do see major divisions between those who support different

political parties: 69% say there are conflicts, which ranks the island

among the top three most politically divided locations. Supporters of

the governing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and nonsupporters are

equally likely to see such political disagreements.

These are

among the findings of a new Pew Research Center survey, conducted from

Feb. 1 to May 26, 2021, among 18,850 adults in 17 advanced economies.

Other key findings include:

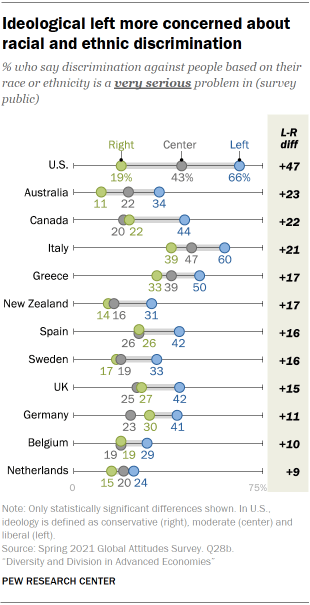

People on the ideological left are often

more likely to say diversity improves their societies, as well as to

describe discrimination as a problem. But when it comes to identifying

conflicts between different racial and ethnic groups, the relationship

varies. In the U.S. and Greece, those on the left are more likely to

describe these racial tensions than those on the right, whereas in

Sweden, Italy and Germany, the opposite is true.

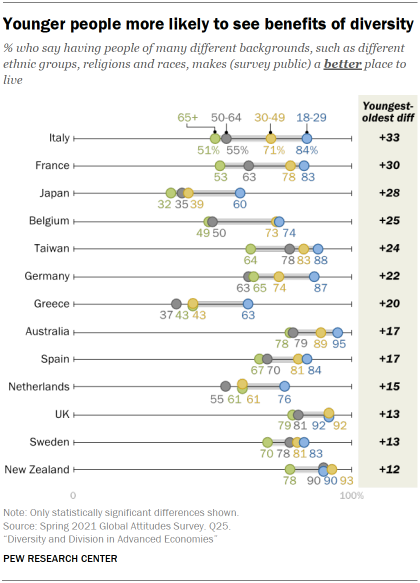

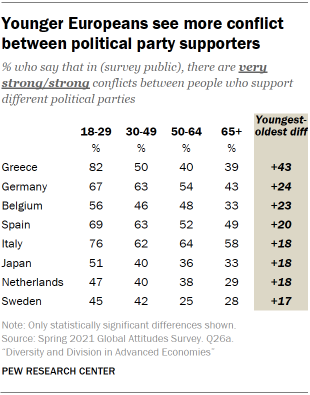

Younger

respondents tend to say people of different backgrounds make their

society a better place to live – but also tend to see more conflicts and

discrimination in their society than older people. For example, in

Greece, around six-in-ten of those under age 30 say having people of

many different ethnic groups, religions and races improves their

society, compared with only around four-in-ten of those ages 65 and

older who say the same. Yet those under 30 are also around twice as

likely – or more – as those ages 65 and older to report conflicts

between people who support different parties, between different ethnic

groups, and between different religious groups.

In some publics,

people who think the economy is doing well tend to see fewer conflicts

between groups in their society and see more benefits stemming from

diverse people living around them.

Diverse society seen positively in most advanced economies

Across

most of the 17 advanced economies surveyed, majorities – and in many

cases, large majorities – say that having people of many ethnic groups,

religions and races makes their society a better place to live. This

opinion is most strongly held in Singapore, where 92% say that having

people of different ethnic groups, religions and races makes Singapore a

better place to live. Eight-in-ten or more in New Zealand, the U.S.,

Canada, the UK, Australia and Taiwan also say having people of many

different backgrounds makes for a better place to live.

But this

opinion is not universally held. About half of Greek and Japanese

adults say that having a diverse society makes their country a worse

place to live. Still, this represents significant declines from 2017,

when majorities in Greece (62%) and Japan (57%) said diversity makes

their country a worse place to live.

In

fact, attitudes have generally become more open to diversity since the

question was last asked in 2017. The share who say having people of many

different backgrounds makes their society a better place to live has

increased significantly in nine of 11 countries where the question was

posed in both 2017 and 2021. Views have changed most dramatically in

Greece, where 45% now say having people of many different backgrounds

makes their society better compared with just 21% who held that view in

2017, an increase of 24 percentage points.

While majorities in

nearly every survey public agree that diversity in society is a

positive, younger people and those with more education are significantly

more likely than older people and those with less education to hold

this opinion.

For example, 84% of Italians ages 18 to 29 say

having people of many different backgrounds makes Italy a better place

to live, while about half (51%) of Italians ages 65 and older agree.

Italy also has the largest attitudinal gap between those with a

postsecondary education or more and those with less than a postsecondary

education: 89% of more educated Italians view diversity positively,

compared with 58% of educated Italians with less education, a gap of 31

points.

Wealthier people express more positive views of

diversity than those with lower incomes in some of the places surveyed.

For instance, nine-in-ten Britons with higher incomes say having people

of many different ethnic groups, races and religions makes the UK a

better place to live; eight-in-ten Britons with lower incomes say the

same. Income gaps also appear in Italy, Australia, France, Belgium,

Sweden, Canada, Singapore and the U.S.

And in 12 of 17 advanced

economies, those who say the current economic situation is good are

significantly more likely to say diversity makes their society better

than those who say the economic situation is bad.

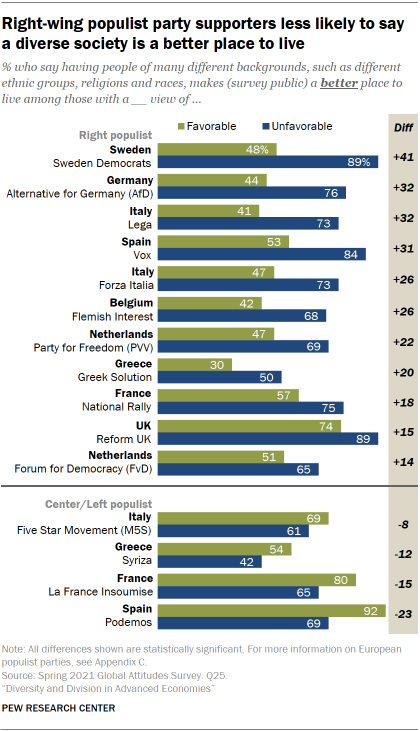

Large

divides on the question appear between supporters and nonsupporters of

right-wing populist parties in Europe, many of which advocate for strict

anti-immigration policies and openly oppose multiculturalism (for more on how populist parties are defined, see Appendix C). The divide is largest between those with favorable and unfavorable views of Sweden Democrats (48% vs. 89%, respectively).

On

the other hand, supporters of center and left-wing populist parties in

Italy, Greece, France and Spain are more likely to say diversity makes

their country a better place to live.

Discrimination seen as a serious problem in most advanced economies

When

it comes to racial and ethnic discrimination, a median of 67% say it is

a serious or very serious problem in their own society, though views

vary widely.

Americans and Canadians generally agree that racial

and ethnic discrimination is at least a serious problem in their

respective countries. Around three-quarters of Americans think so, as do

around two-thirds of Canadians.

Across Europe, a median of

around seven-in-ten say discrimination against people based on their

race or ethnicity is a serious or very serious problem, while only about

a quarter think it is not too serious of a problem or not a problem at

all. Italy reports the highest percentage of adults who say racial and

ethnic discrimination is a very serious problem (46%).

In the

Asia-Pacific region, views on the topic vary more widely than in Europe

and North America. At least six-in-ten Australians and New Zealanders

say discrimination against people based on their race and ethnicity is a

serious or very serious problem in their country. Taiwan, Singapore and

Japan are the only places surveyed where majorities say discrimination

is either not too serious or not a problem at all.

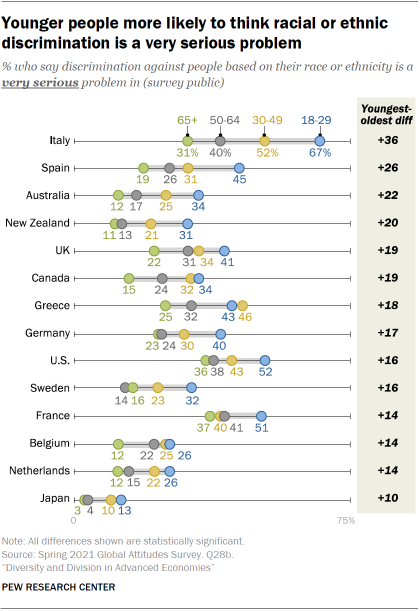

In

14 of the 17 advanced economies surveyed, younger people are

significantly more likely than older people to say racial or ethnic

discrimination is a very serious problem. This is is especially true in

Italy, where two-thirds of Italians ages 18 to 29 say racial or ethnic

discrimination is a very serious problem, while only about one-third of

Italians ages 65 and older say the same.

Age gaps of 20

percentage points or more also appear in Spain, Australia and New

Zealand. Even in Japan, where only 7% overall say racial or ethnic

discrimination is a very serious problem, adults under 30 are 10 points

more likely than those 65 and older to hold this view (13% and 3%,

respectively).

While there are few differences in responses by

education or income, women are more likely than men to say racial or

ethnic discrimination is a serious or very serious problem in 13 of 17

publics surveyed.

In keeping with previous findings that ideological divisions in the U.S. are wider

than in other countries, the U.S. is by far the most ideologically

divided on the question of racial and ethnic discrimination. About

two-thirds of Americans on the left say racial and ethnic discrimination

in the U.S. is a very serious problem; only 19% of Americans on the

right hold that view.

Still, there are significant left-right

divides in many other countries on the seriousness of racial and ethnic

discrimination. Australians, Canadians and Italians on the left are more

than 20 points more likely than those on the right to say

discrimination based on race or ethnicity is a very serious problem in

their country.

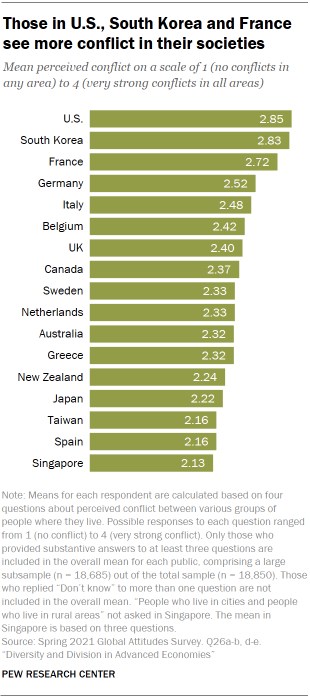

To

understand how people view divisions in their societies, we asked about

the strength of the conflict that people see between various groups,

including: 1) those who support different political parties, 2) those

with different ethnic or racial backgrounds, 3) those who practice

different religions and 4) those who live in cities compared with those

who live in rural areas. (For more on each society’s composition across

these four dimensions, see Appendix A.)

We

created a summary index of perceived social conflict by averaging

responses across the four questions. Higher values indicate that, on

average, people see more friction between groups in their society.

Perceived

conflict is highest in the U.S., South Korea and France. Notably,

Koreans are much more likely than others in the Asia-Pacific region to

view conflict among social groups. Four of the five publics with the

lowest conflict scores are in this region: Singapore, Taiwan, Japan and

New Zealand. In contrast, conflict scores tend to be relatively higher

in North America and Europe. Here, Spain is the exception, with a

generally low average. Though the overall magnitude varies across the 17

publics surveyed, most show the same pattern when it comes to which

groups are more or less likely to be divided. Overall, people see the

strongest conflicts among those who support different political parties

and those with different ethnic or racial backgrounds. In comparison,

people tend to see less conflict among those who practice different

religions. And relatively few see strong tensions between people who

live in cities and people who live in rural areas.

Perceived conflict between supporters of different political parties

A

median of 50% across the 17 publics surveyed say there are strong

conflicts between people who support different political parties. This

sentiment is particularly high in the U.S. and South Korea, where

nine-in-ten see tensions between different party backers. At least half

in both countries say these conflicts are very strong.

Compared

with their southern neighbors, Canadians see their country as much less

divided across party lines. Only 44% think there are strong partisan

conflicts. (The survey was conducted before Canadian Prime Minister

Justin Trudeau called a snap election in August 2021.)

In

Europe, majorities in France, Italy, Spain and Germany say there are

strong conflicts between supporters of different political parties. A

quarter or more in France and Italy see these tensions as very strong.

Sweden and the Netherlands are among the least politically divided

countries in this region, with 35% and 38% seeing strong conflicts,

respectively. While people in South Korea are the most likely in the

Asia-Pacific region to see strong conflicts between different party

backers, nearly seven-in-ten in Taiwan hold the same view. Relatively

few in the rest of the region say there are strong partisan conflicts in

their society. Singaporeans feel particularly united when it comes to

politics; 17% say there are no conflicts at all.

In

many of the European countries surveyed, younger adults are more likely

than those ages 65 and older to say there are strong conflicts between

supporters of different political parties. Younger and older Greeks are

especially divided. Only 39% of Greeks ages 65 and older think there are

strong partisan tensions in their country, compared with 82% of Greeks

ages 18 to 29.

Similar, though smaller, differences can also be

seen in Germany, Belgium, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands and Sweden.

Outside of Europe, a third of older adults in Japan see their country as

politically divided, compared with roughly half of those under 30.

Notably,

there are very few differences by ideology or support for the governing

party. In the U.S., for example, Republicans and Republican-leaning

independents are just as likely as Democrats and Democratic-leaning

independents to think there are strong partisan tensions in the U.S.

(both 90%).

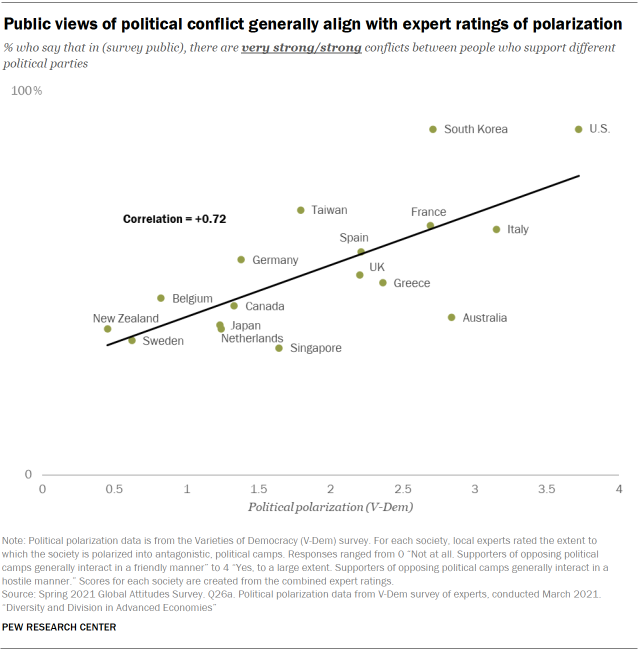

There is a relatively strong correlation between

perceptions of partisan conflict among the general public and the views

of experts (r=+0.72). In publics where larger shares of survey

respondents say there is tension between different party backers,

experts generally report greater political polarization (according to

the V-Dem

political polarization measure, which quantifies the extent to which

trained coders view each public as polarized into antagonistic political

groups).

Additionally,

the share of people across the 17 publics surveyed who say there are

very strong conflicts between supporters of different political parties

is moderately correlated (r=+0.59) with the share of seats received by

the second-largest party in an election. For example, in the 2020

election in Taiwan, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) received 54%

of the seats in Taiwan’s legislature while the Kuomintang (KMT) – the

second-largest party – received 34%, making for a relatively divided

chamber. Roughly three-in-ten in Taiwan say there are very strong

partisan conflicts in their society. Toward the other end of the

spectrum, one can look at Japan, where the ruling Liberal Democratic

Party (LDP) won 59% of seats in the House of Representatives in the 2017

election, while the second-largest party – the Constitutional

Democratic Party (CDP) –received just 11%. In Japan, a much smaller

share of the public describes very strong tensions between different

party supporters (8%).

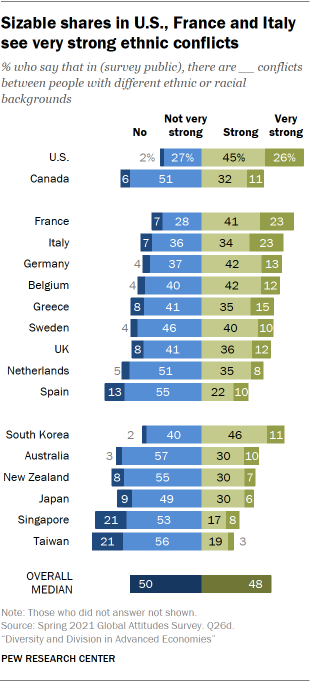

Perceived conflict between people with different ethnic or racial backgrounds

Many

people across the 17 advanced economies surveyed see strong conflicts

between people with different ethnic or racial backgrounds (a median of

48%). People in the U.S. (71%), France (64%) and Italy (57%) are

particularly likely to view these tensions as strong, with around a

quarter in each country who say they are very strong. While majorities

in South Korea and Germany also say there are strong conflicts in their

society, only around one-in-ten rate them as very strong.

In

Sweden, Belgium and the Netherlands, people are more likely to say there

are strong conflicts between people from different ethnic or racial

backgrounds than between people who support different political parties.

In Sweden, for example, while only 35% see their country as politically

divided, 50% see tensions based on race or ethnicity.

In about

half of the publics surveyed, women are more likely than men to say that

there is friction between people from different ethnic backgrounds. For

example, 49% of German men compared with 61% of German women hold this

view. Similar gender differences are seen in Belgium, France, Greece,

Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand and Taiwan.

Overall, there

are few ideological differences. In Germany, Sweden and Italy, those on

the right of the ideological spectrum are more likely than those on the

left to see strong conflicts between people from different racial and

ethnic backgrounds. This pattern is reversed in Greece and the U.S.,

with those on the left more likely to say that there are racial or

ethnic tensions in their countries.

Consistent with the

ideological differences in the U.S., Democrats (82%) are much more

likely than Republicans (58%) to say there are strong conflicts based on

race and ethnicity in their country. And Black Americans (82%) see more

conflict between people of different racial and ethnic backgrounds than

White (69%) and Hispanic Americans (70%).

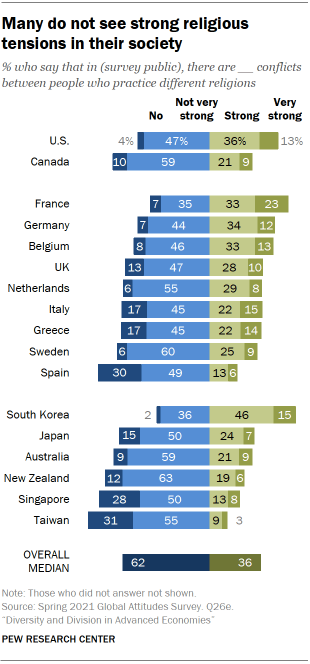

Perceived conflict between people who practice different religions

Overall,

fewer people see strong religious conflicts, compared with conflicts

based on politics or race. A median of 36% across the 17 publics

surveyed say there are strong conflicts between people who practice

different religions in their society.

South Korea and France are

the only places surveyed where more than half of people say there are

strong divisions based on religious beliefs. And in France, almost a

quarter say these conflicts are very strong.

Roughly half of

Americans say there are strong conflicts between people who practice

different religions in their country, including 13% who say there are

very strong conflicts.

In Europe, people in Spain are by far the

least likely to say there are strong religious tensions. Only 19% of

Spaniards hold this view. More say that there are no conflicts between

different religious groups at all in their country (30%).

Again,

South Korea is an outlier in the Asia-Pacific region. Koreans are

nearly twice as likely as those in Japan, which has the second-highest

share in the region, to say there are religious tensions in their

country. In contrast, roughly three-in-ten in Singapore and Taiwan say

there are no religious conflicts at all.

Adults under 30 are

more likely than those ages 65 and older to see strong religious

divisions in Greece, Belgium, Japan, Italy, the U.S., Spain and Taiwan.

And again, Greeks are the most polarized by age, with 60% of younger

adults and 24% of older adults saying there are strong conflicts based

on religion in their country.

Different kinds of religious conflict

The

survey included two questions measuring perceived religious conflict:

1) conflict between people who practice different religions and 2)

conflict between people who are religious and people who are not

religious. The separate questions were included to determine if people

viewed tensions between, for example, Christians and Muslims, as

stronger or weaker than conflicts between people who identify with a

religion and those who do not.

The differences between these two

questions were negligible. In most countries, similar shares say there

are strong conflicts between people who practice different religions and

between those who are religious and those who are not. Across the 17

publics surveyed, the correlation between the questions was extremely

high (r=+0.97). Considering the similarities between the questions, we

focus on just one for our analysis: conflict between people who practice

different religions.

However, perceptions of religious conflict

differ somewhat by ideology in several countries. For example,

conservatives in the U.S. are more likely to see strong conflicts

between people who are religious and those who are not (50%) than

between different religious groups (39%). Liberals respond nearly the

same to both questions. And in Sweden, people on the left are less

likely to see conflicts between people who are religious and those who

are not (12%) than between different religious groups (26%).

In

Germany, Canada and Italy, there are ideological divides in the extent

to which people see conflicts between those who are religious and those

who are not, with people on the right more likely to see conflicts than

those on the left. But people on the left and right in these countries

agree on the extent to which there are conflicts between different

religious groups.

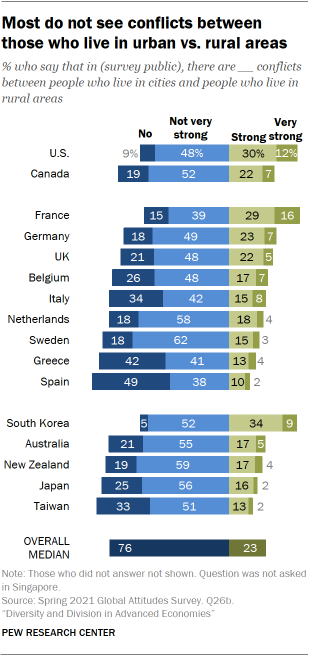

Perceived conflict between people who live in cities and people who live in rural areas

A

median of just 23% say there are strong or very strong conflicts

between people who live in cities and people who live in rural areas.

Half say there are not very strong conflicts and 20% say there are no

conflicts at all between these groups. (Medians are based on 16 publics.

This question was not asked in Singapore, a geographically small island

nation with an entirely urban population.)

Again, France, South

Korea and the U.S. stand out as particularly divided. Roughly 45% in

each country say there are strong or very strong tensions based on

geography. Elsewhere, no more than three-in-ten share this sentiment.

Spaniards

are the most likely to say that there are no conflicts at all between

those who live in cities and those who live in rural areas (49%). In

Europe, at least a quarter in Belgium, Italy and Greece say the same.

Similarly,

many in the Asia-Pacific region – with the exception of South Korea –

say there are not very strong or no conflicts based on what type of area

people live in. Roughly one-in-five or more in New Zealand, Australia,

Japan and Taiwan say there are no divisions at all between city-dwellers

and people who live in rural areas.

People across the

ideological spectrum tend to agree that there are limited conflicts

based on the type of area people live in. In the U.S., however, people

on the left (53%) are more likely than those on the right (38%) to say

that there are strong or very strong conflicts between people who live

in urban areas and people who live in rural areas.

In six

European countries – Belgium, the UK, Germany, France, the Netherlands

and Greece – those with a secondary education or below are more likely

than people with postsecondary education to say that there is friction

based on where people live in their country. In the U.S., the opposite

is true; people with more education are more likely than those with less

to say there are strong conflicts between people in urban and rural

areas.

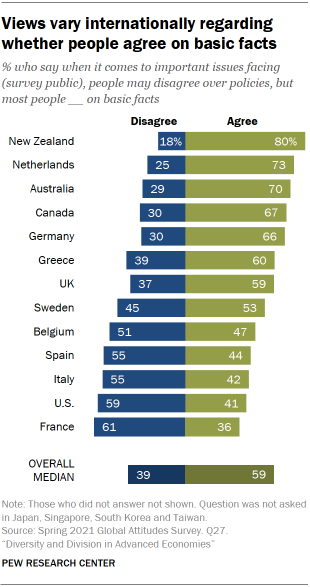

Majorities of some publics say most people agree on basic facts

A

median of 39% believe there are fundamental disagreements over basic

facts in their society. In France and the U.S., about six-in-ten say

most people in their country disagree over basic facts, while half or

more also hold this view in Italy, Spain and Belgium. In contrast,

roughly two-thirds or more in New Zealand, the Netherlands, Australia,

Canada and Germany think most people agree on basic facts, even if they

disagree about policies.

This high sense of disagreement over facts may be due, at least in part, to struggles to combat pandemic-related conspiracy theories.

In most places surveyed, those who believe COVID-19 has made their

society more divided are much more likely to say people disagree over

basic facts than those who say COVID-19 has made their society more

united.

Perception of political conflicts is strongly tied to

whether adults think their fellow citizens agree or disagree on basic

facts. In every public surveyed, those who say there are very strong or

strong conflicts between people who support different political parties

are more likely to think people disagree on basic facts. This divide is

largest in Sweden: 62% of Swedes who say there are political conflicts

think most people disagree about basic facts, compared with only 37% of

Swedes who say there are not very strong or no conflicts between people

who support different political parties.2

Views on the topic are

closely related to views of the governing party or parties in each

place surveyed. Outside of the U.S. and Italy, in every other public

those with unfavorable views of the governing coalition are more likely

to say most people disagree about basic facts than those with favorable

views of the government.

Rubén Weinsteiner