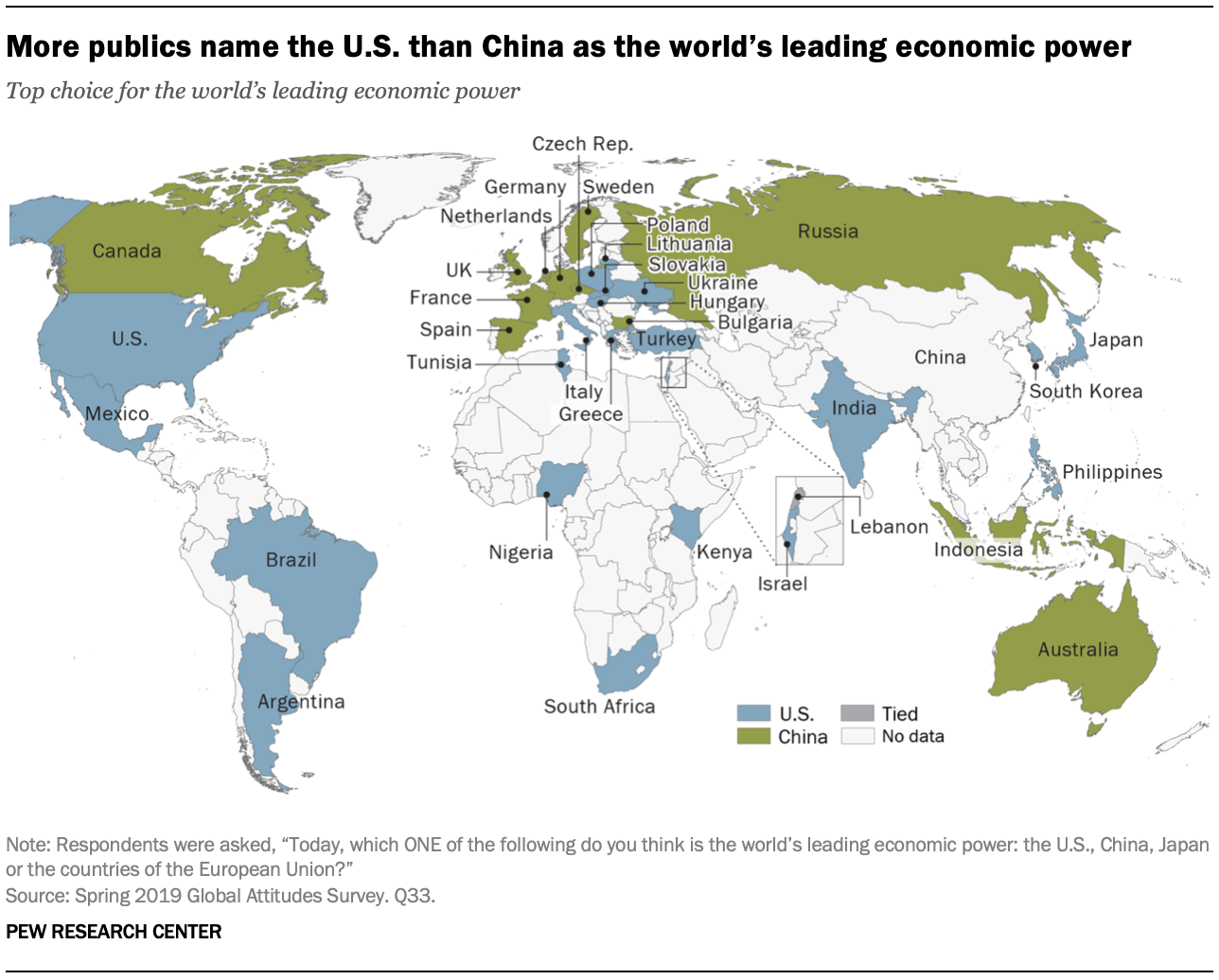

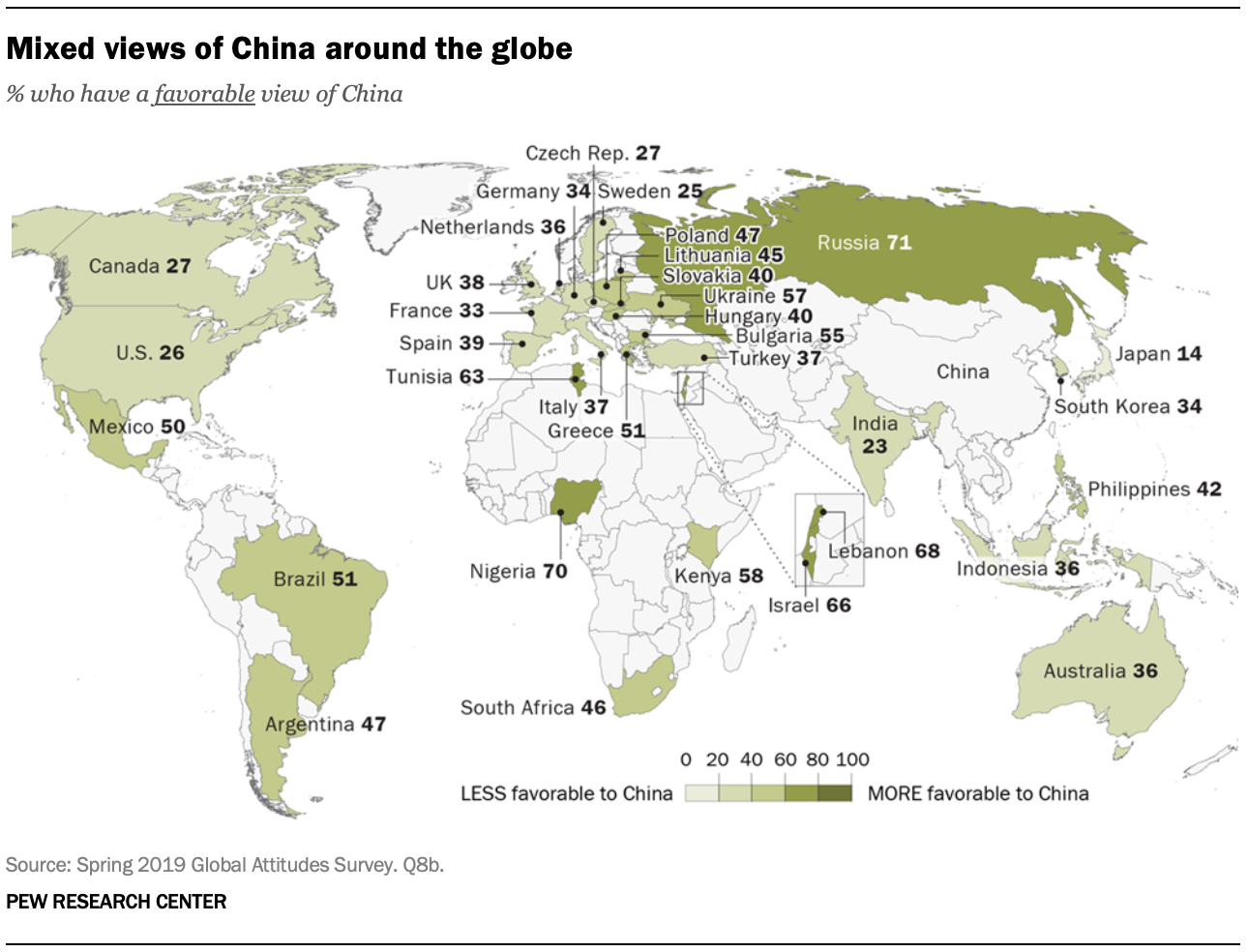

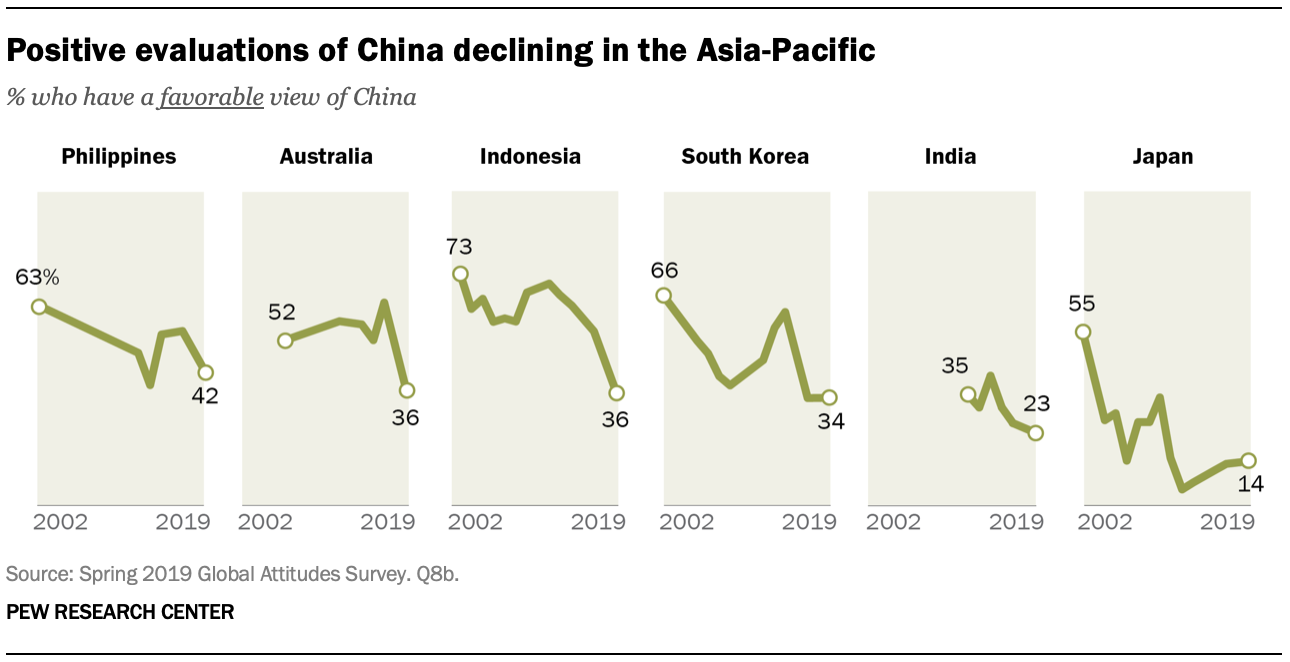

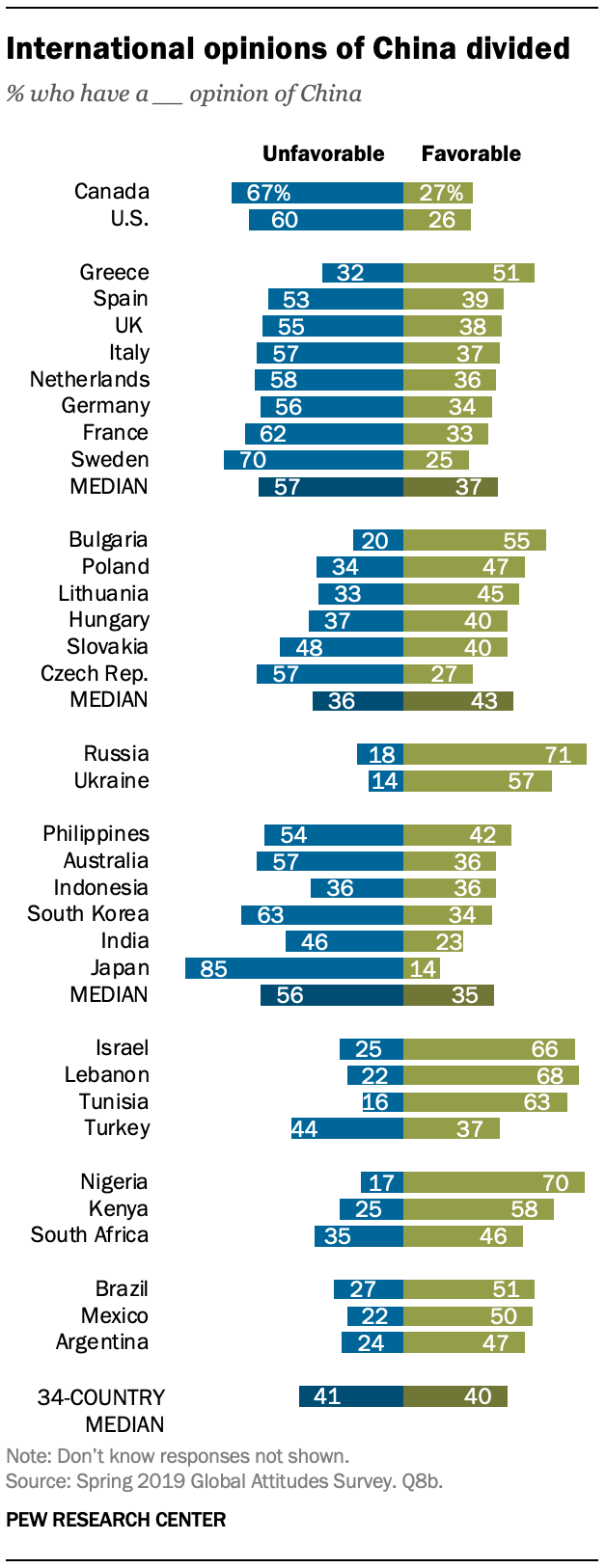

Around the globe, people are divided in their opinions of China.

A median of 40% across 34 countries surveyed have a favorable view of

China, while a median of 41% have an unfavorable opinion. The country’s

most positive ratings come from Russia (71% favorable), Nigeria (70%)

and Lebanon (68%). The most negative views are found in Japan (85%

unfavorable), Sweden (70%) and Canada (67%). (For more information on

global views of China, see “People around the globe are divided in their opinions of China.”)

Around the globe, people are divided in their opinions of China.

A median of 40% across 34 countries surveyed have a favorable view of

China, while a median of 41% have an unfavorable opinion. The country’s

most positive ratings come from Russia (71% favorable), Nigeria (70%)

and Lebanon (68%). The most negative views are found in Japan (85%

unfavorable), Sweden (70%) and Canada (67%). (For more information on

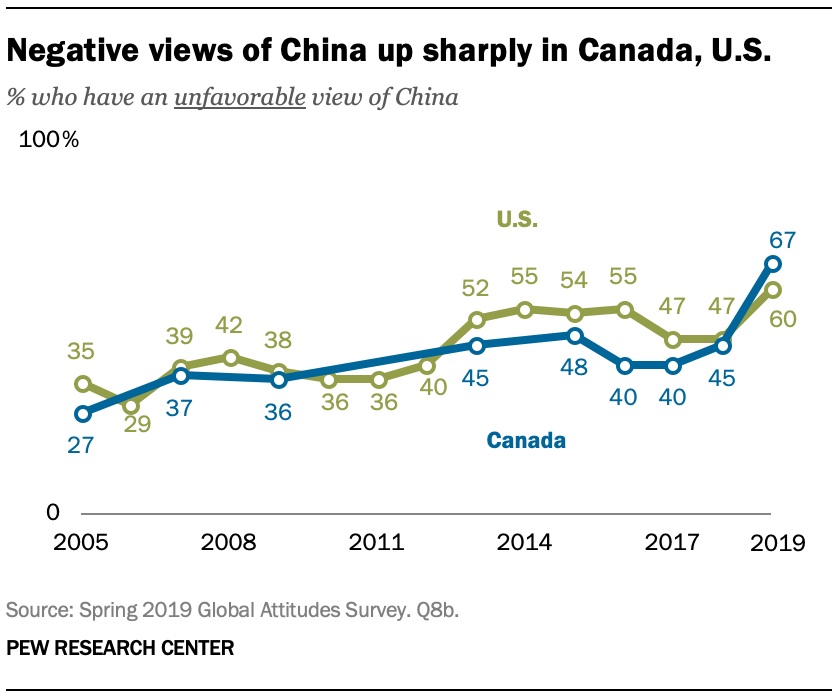

global views of China, see “People around the globe are divided in their opinions of China.”)  In

Canada and the United States, the increase in unfavorable views this

year represents the largest year-over-year change since the question was

first posed in 2005. In Canada, unfavorable opinions increased 22

percentage points in the wake of the high-profile arrest of technology company Huawei’s chief financial officer and the ensuing Chinese detainment of two Canadian nationals who still remain in Chinese custody, while in the U.S. unfavorable opinions increased 13 points.

In

Canada and the United States, the increase in unfavorable views this

year represents the largest year-over-year change since the question was

first posed in 2005. In Canada, unfavorable opinions increased 22

percentage points in the wake of the high-profile arrest of technology company Huawei’s chief financial officer and the ensuing Chinese detainment of two Canadian nationals who still remain in Chinese custody, while in the U.S. unfavorable opinions increased 13 points. Age is a factor in how people view China. In 19 countries, those ages 18 to 29 are more likely than those ages 50 and older to hold a favorable view of China.

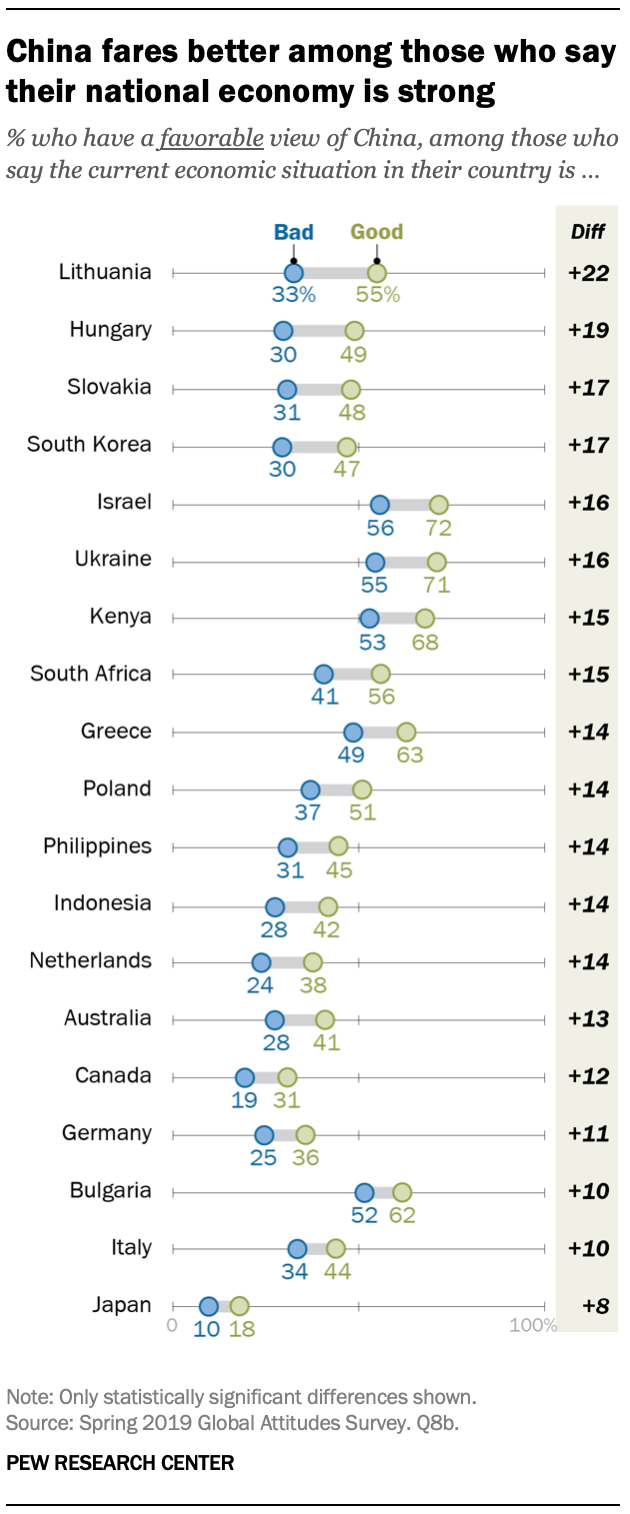

In

19 countries, those who say their national economic situation is good

have a more positive outlook on China. In Lithuania, 55% of those who

grade their economy as good have a favorable view of China; just 33% of

those who say the economy is in poor shape share that opinion, a

22-point gap. Similarly large differences exist in Hungary (19 points),

Slovakia (17), South Korea (17), Israel (16), Ukraine (16), Kenya (15)

and South Africa (15).

In

19 countries, those who say their national economic situation is good

have a more positive outlook on China. In Lithuania, 55% of those who

grade their economy as good have a favorable view of China; just 33% of

those who say the economy is in poor shape share that opinion, a

22-point gap. Similarly large differences exist in Hungary (19 points),

Slovakia (17), South Korea (17), Israel (16), Ukraine (16), Kenya (15)

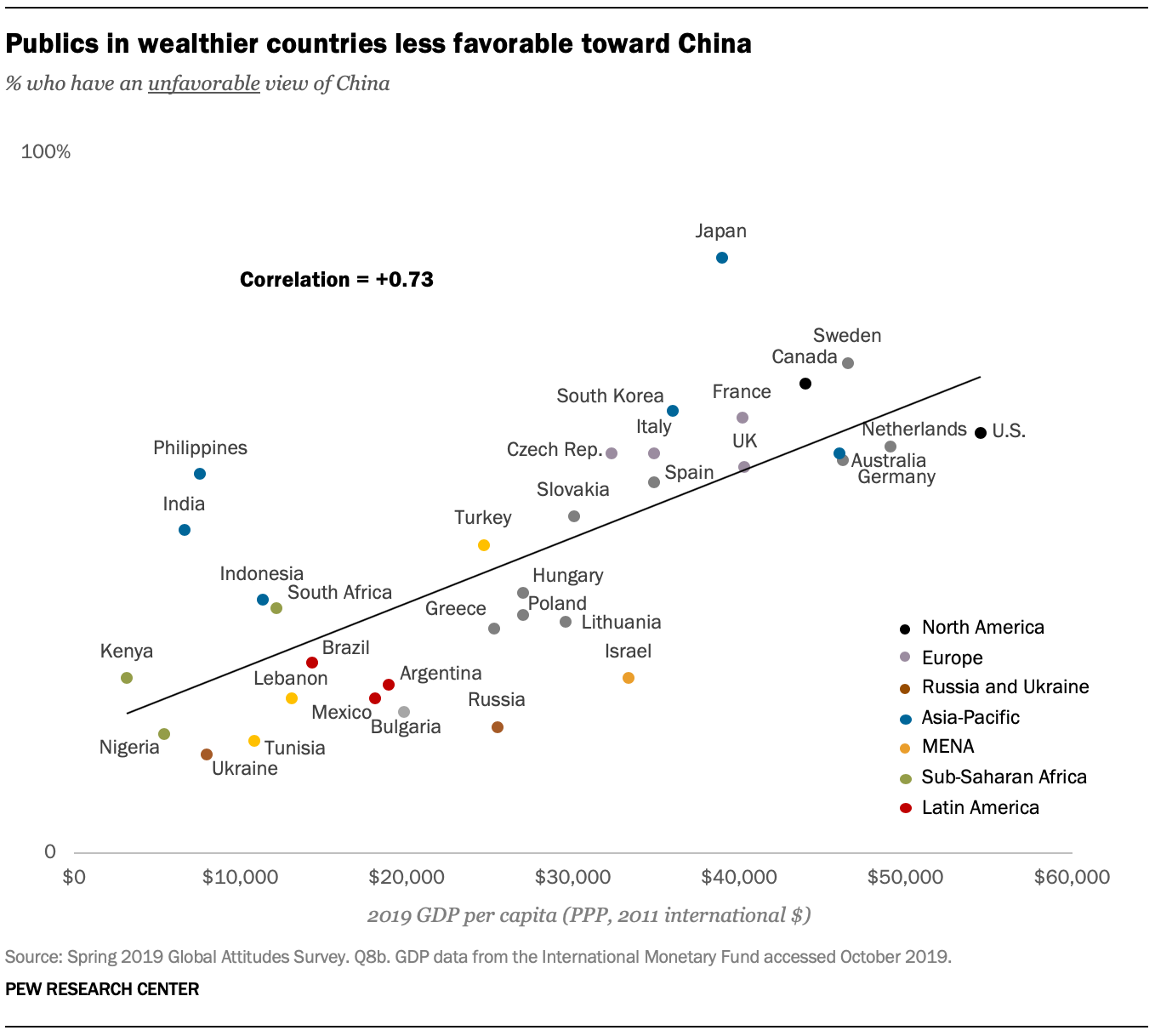

and South Africa (15). Views of China tend to be most negative in countries with the highest per capita gross domestic product, including the U.S., Netherlands, Sweden and Germany. At the opposite end of the spectrum, countries with lower GDP per capita are less negative – including Kenya, Nigeria, Ukraine and Tunisia. Japan stands out as being much more negative toward China than other nations with similar levels of wealth, and this may be partially attributed to long-standing historical grievances between the two nations.

The relationship between GDP per capita and unfavorable views of China may be due in part to the relative political freedoms in these countries, as views of China are also closely related to citizens’ enjoyment of their rights. Previous Center research on China illustrated a strong relationship between global views of China and perceptions about the state of civil liberties domestically for Chinese citizens, and a similar pattern continues beyond China’s borders. Countries whose citizens have more freedoms, as measured by Freedom House, tend to have less favorable views of China. For example, Russia’s aggregate Freedom House score is 20 on a 100-point scale, the lowest among the countries included in the survey, but Russians give China the highest favorable rating (71%). On the opposite end of the spectrum, Sweden receives a perfect 100 from Freedom House, while just 25% of Swedes have positive views of China.

Similarly, the higher a country’s perceived level of corruption, as designated by Transparency International, the more favorably that nation tends to view China. Nigerians, for instance, fare the worst on the corruption scale among the countries included in this survey. Meanwhile, 70% of Nigerians have a favorable view of China, second only to Russians. But both the level of civil liberties and corruption within a country closely track with overall GDP per capita.

In contrast, investment from China is only weakly related to views of China across the countries included in this survey. Despite pouring hundreds of billions of dollars into the Belt and Road Initiative, especially in emerging economies, the size of capital investments or construction contracts funded by Beijing in a country is only weakly related to that country’s overall views of China. Indonesia, for example, has received more than $47 billion for capital investment and construction projects from China since 2005, but attitudes toward China in the country are split evenly, with 36% favorable and 36% unfavorable. On the other hand, China has sent Nigeria $44 billion in the same time, and 70% of Nigerians view China favorably.

Countries that receive more exports from China tend to have more negative views of China, though this measure is also strongly associated with GDP per capita. The U.S. and Japan receive the most exports from China among the countries surveyed, and they also have much more negative views of China overall. And while Lebanon, Tunisia and Bulgaria receive relatively few Chinese exports, majorities in these countries view China in a positive light.

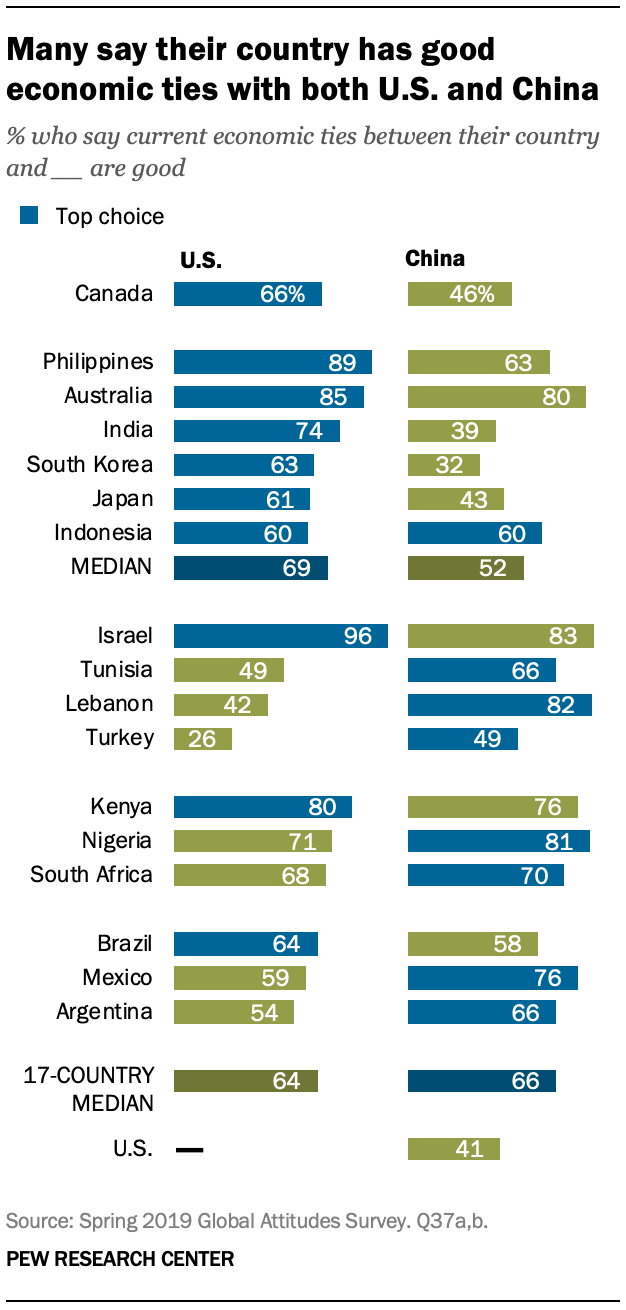

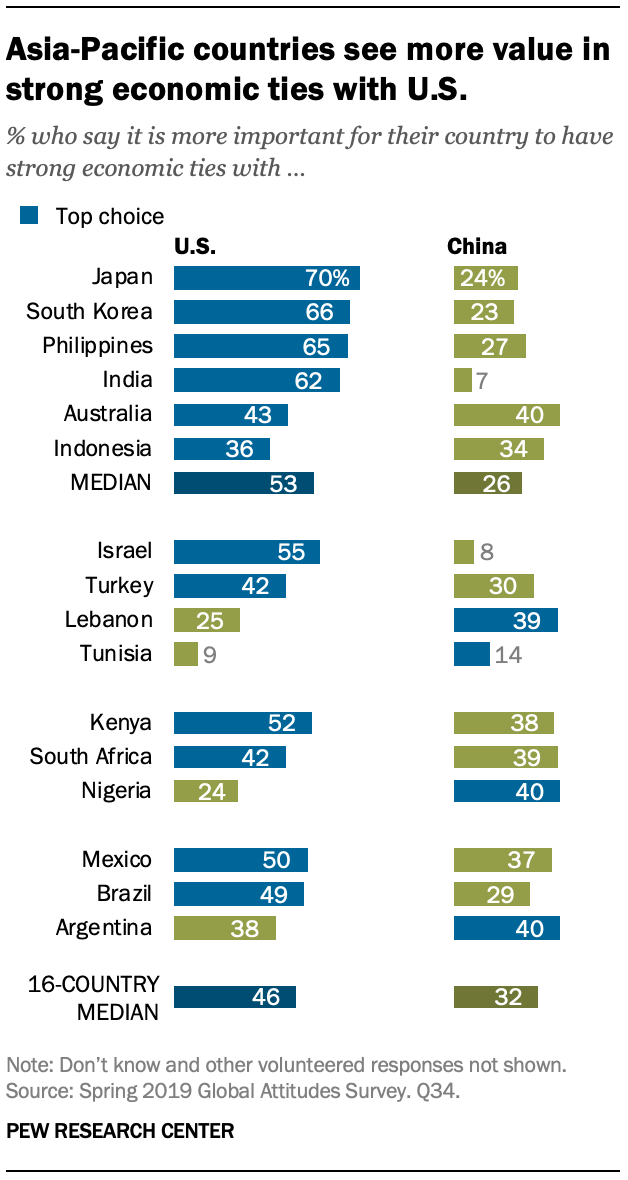

Economic ties with China welcomed in many emerging markets, but some concerns over Beijing’s influence

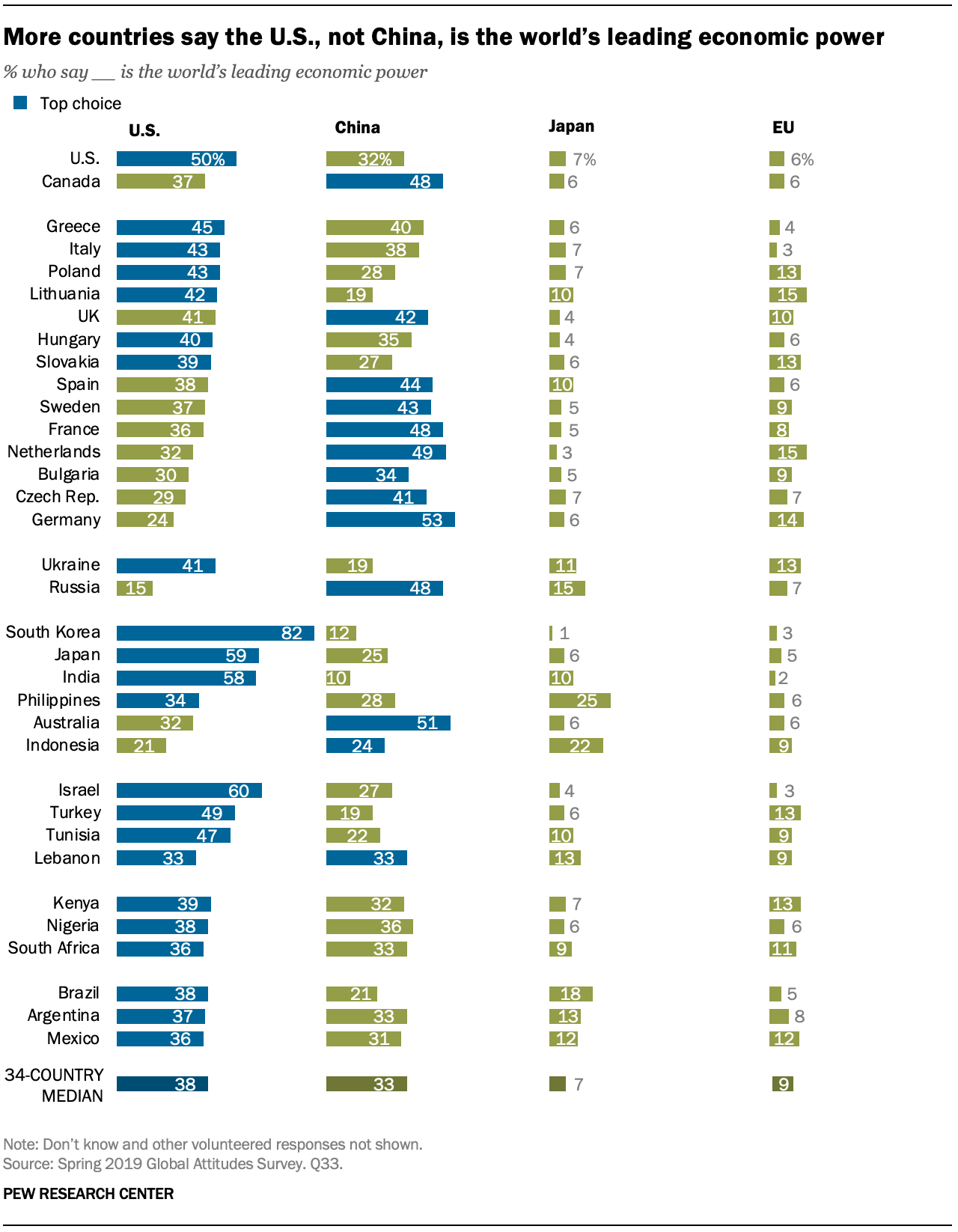

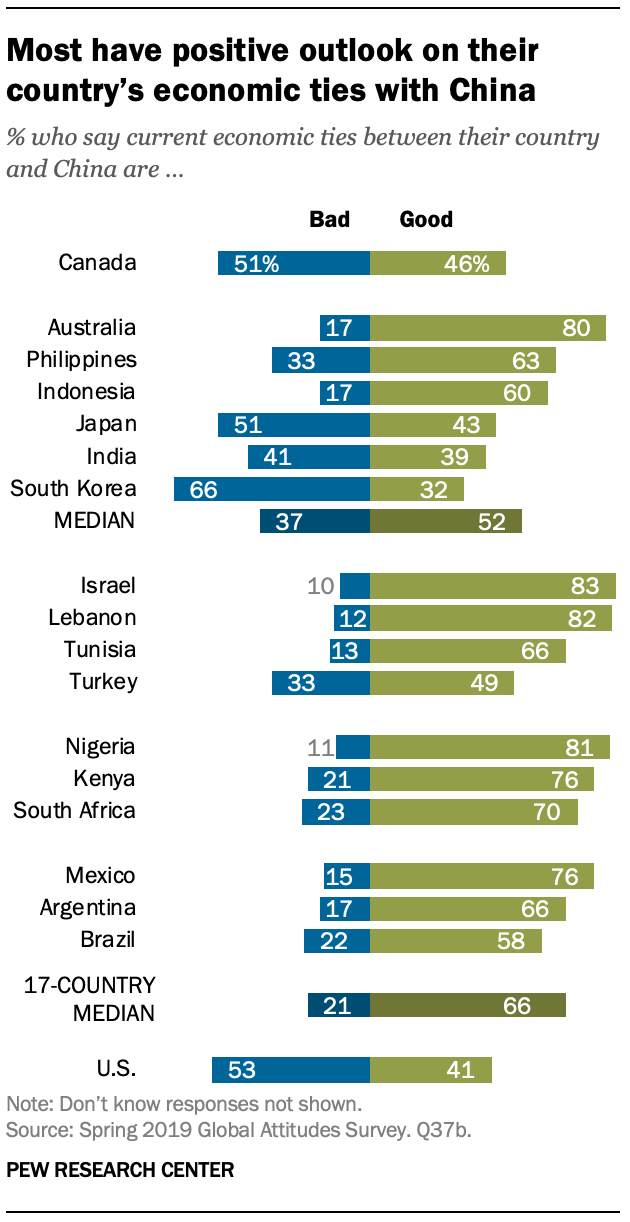

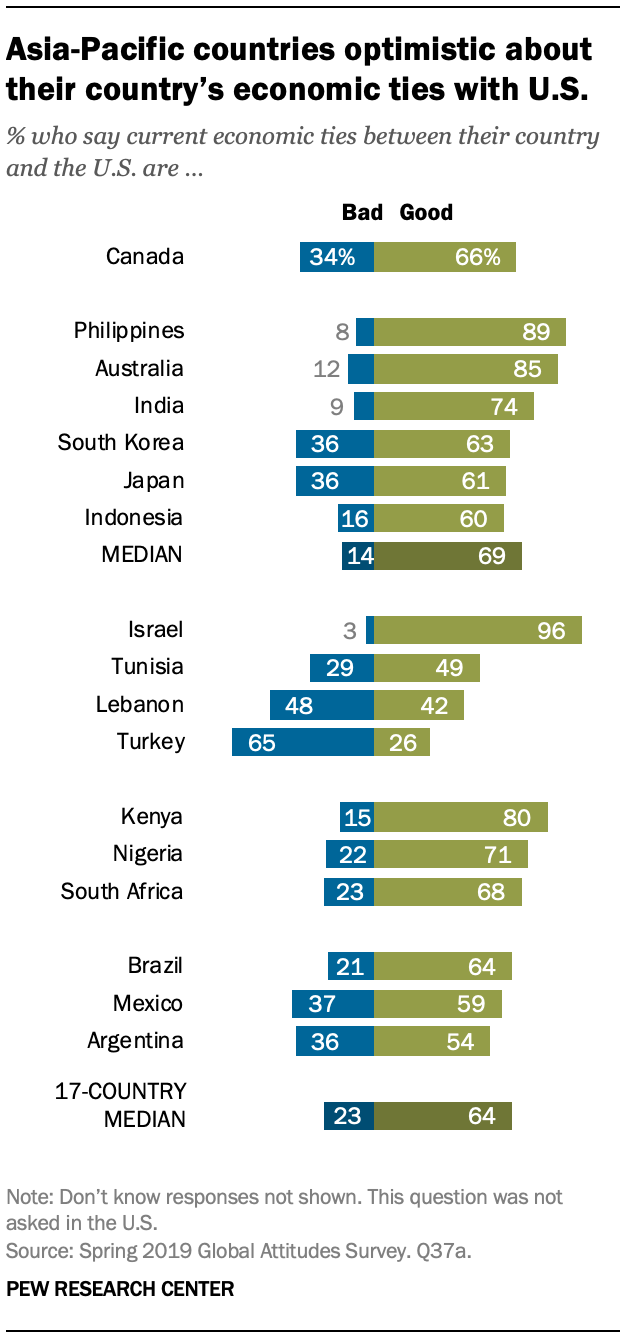

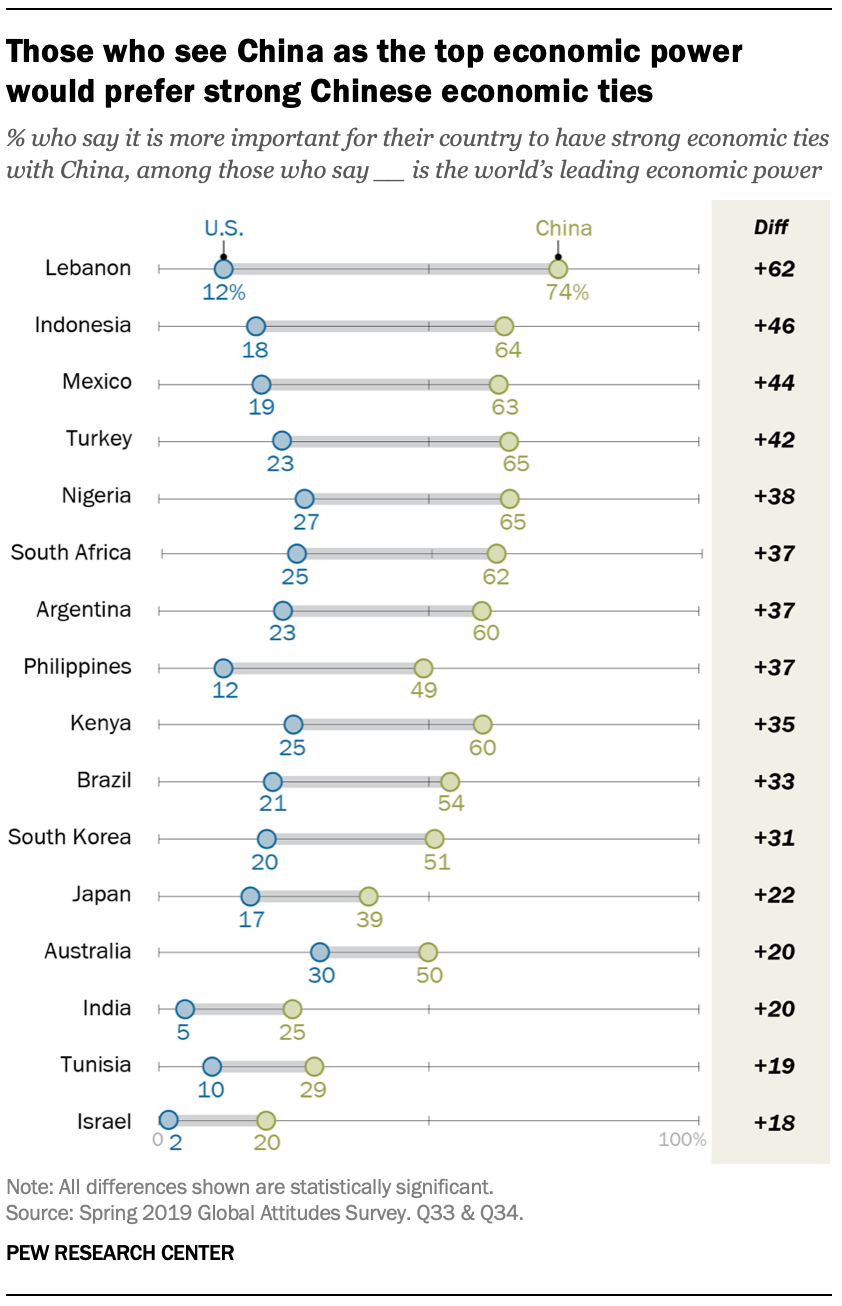

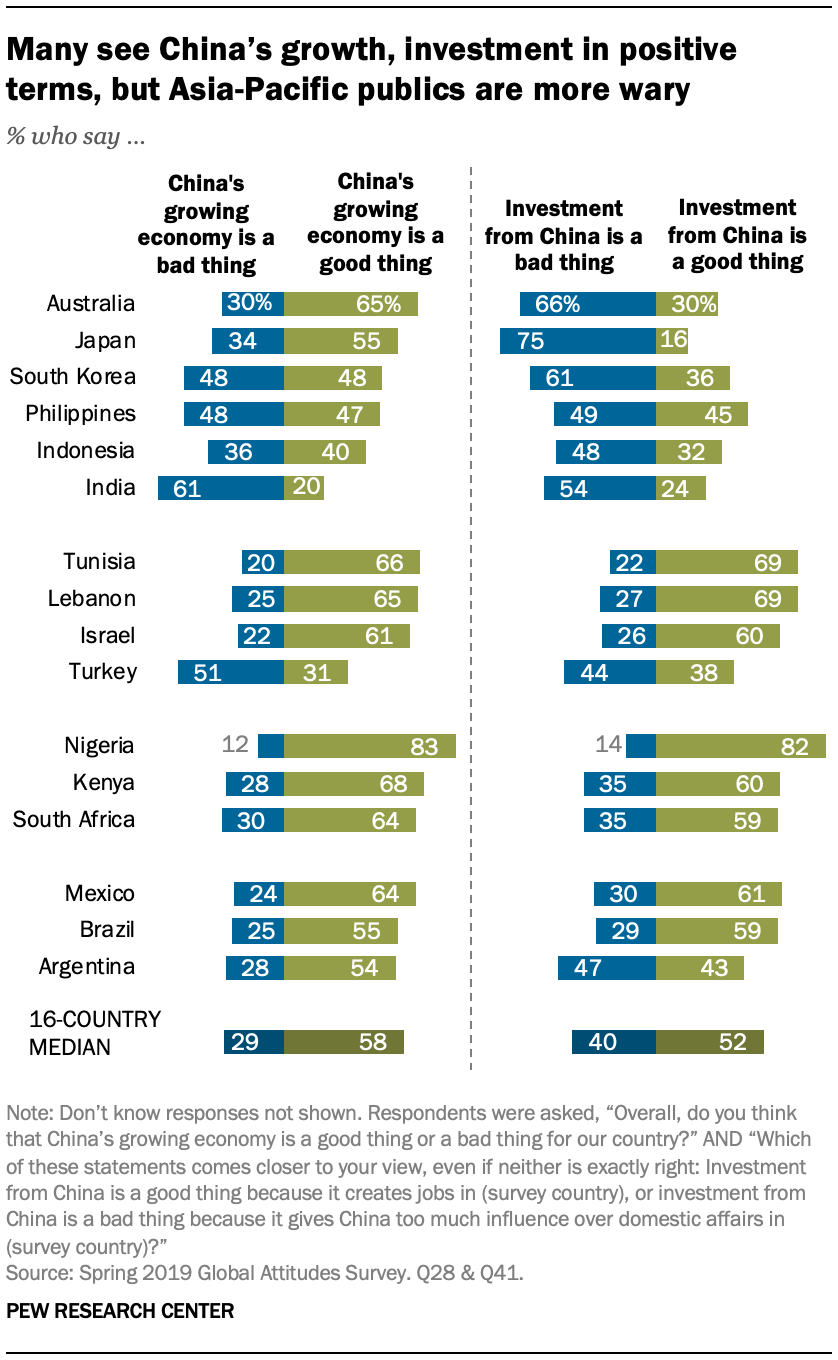

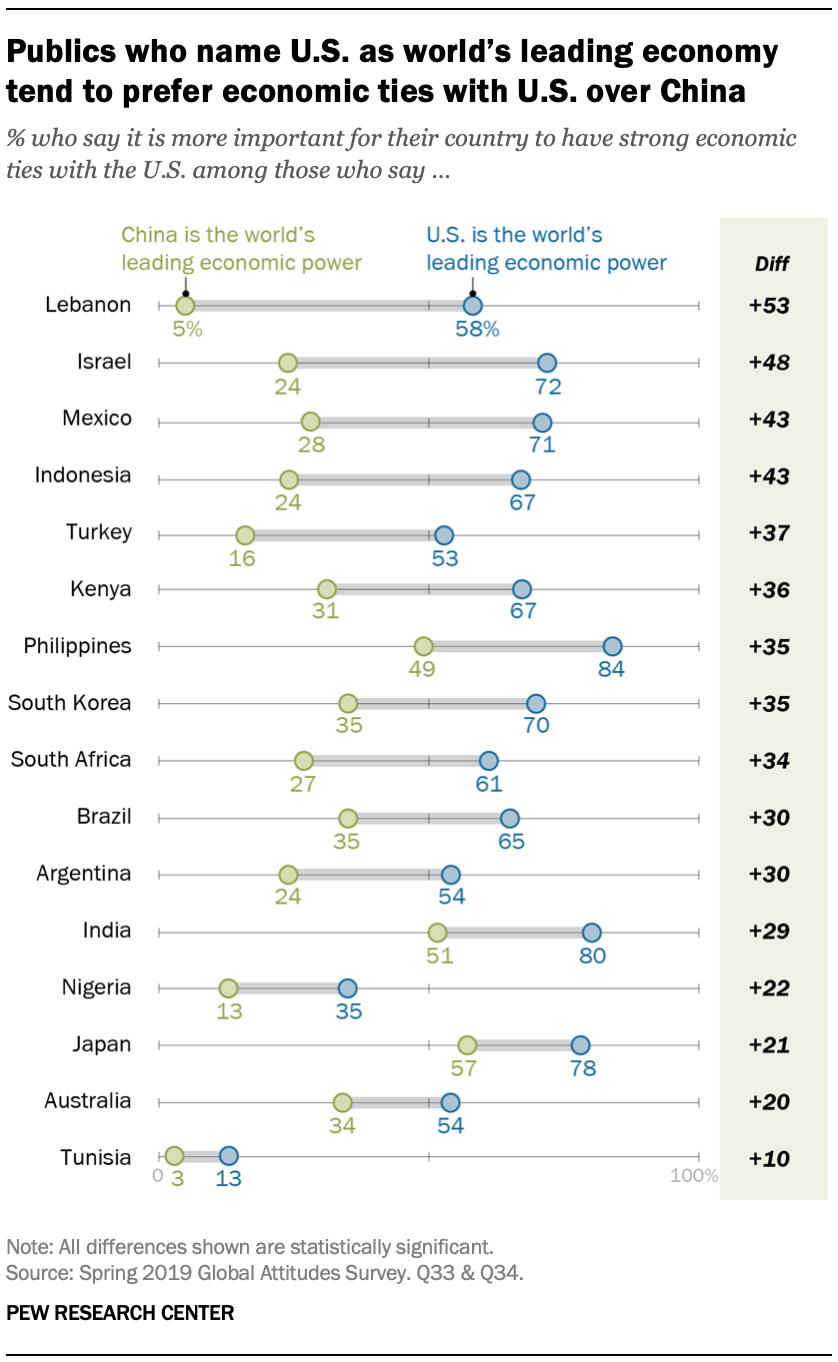

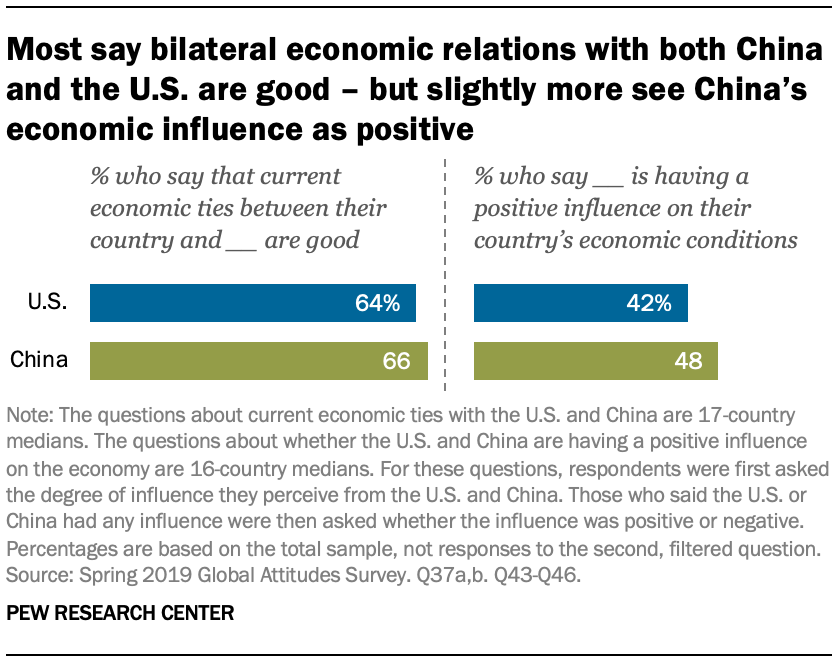

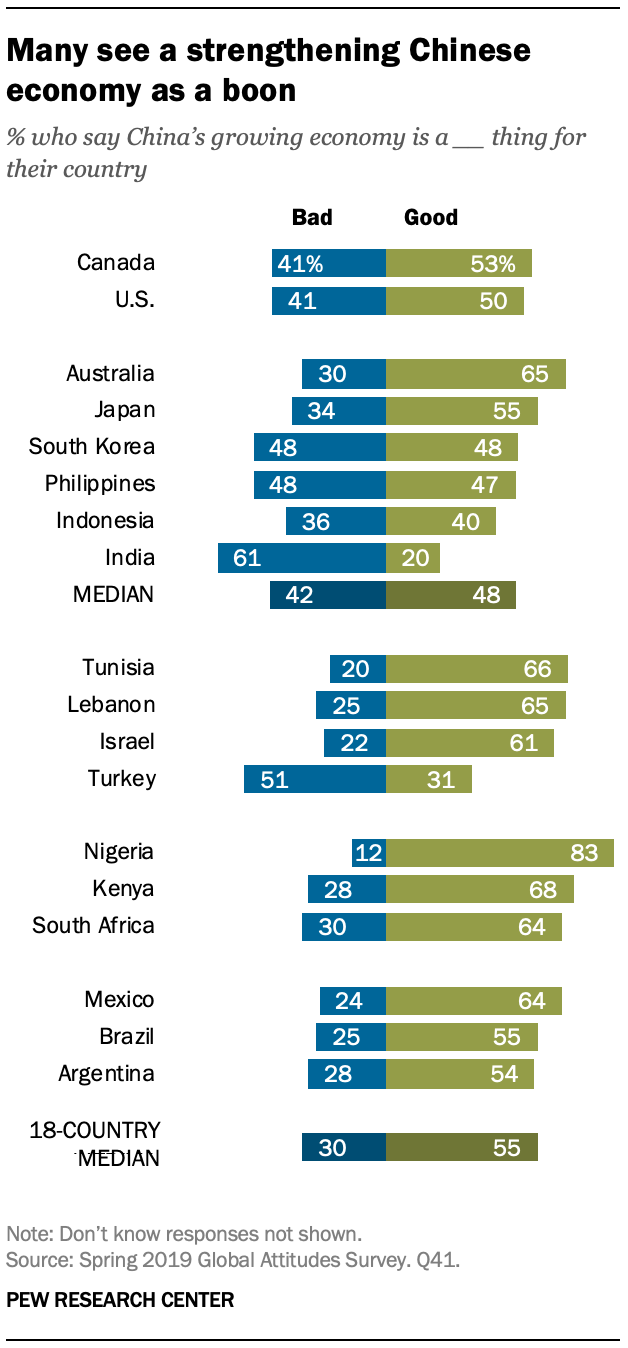

Across

18 countries, more people think China’s growing economy is a good thing

than a bad thing for their country. Overall, a median of 55% see

benefits to a strong Chinese economy; 30% say it is bad for their

country.

Across

18 countries, more people think China’s growing economy is a good thing

than a bad thing for their country. Overall, a median of 55% see

benefits to a strong Chinese economy; 30% say it is bad for their

country. More Canadians and Americans see themselves benefiting from China’s economy than not, though 41% in both countries think this is negative. Majorities in Australia and Japan think a strong economy is mutually beneficial. South Korea, the Philippines and Indonesia have relatively mixed views. A majority of Indians, however, see a growing Chinese economy as a bad thing for their country – the most among all of the publics surveyed.

A majority of Israelis and pluralities of Lebanese and Tunisians believe they benefit from China’s growing economy.

Throughout Africa and Latin America, most say China’s growing economy is a good thing for their country. This ranges from 83% in Nigeria to 54% in Argentina.

And in nine countries, thinking your own national economy is doing well also relates to more positive views of China’s economic growth. Indonesia and the Philippines have the most dramatic differences; people who think their country’s economy is in good shape are more likely to see China’s economic growth positively by 21 and 19 points, respectively.

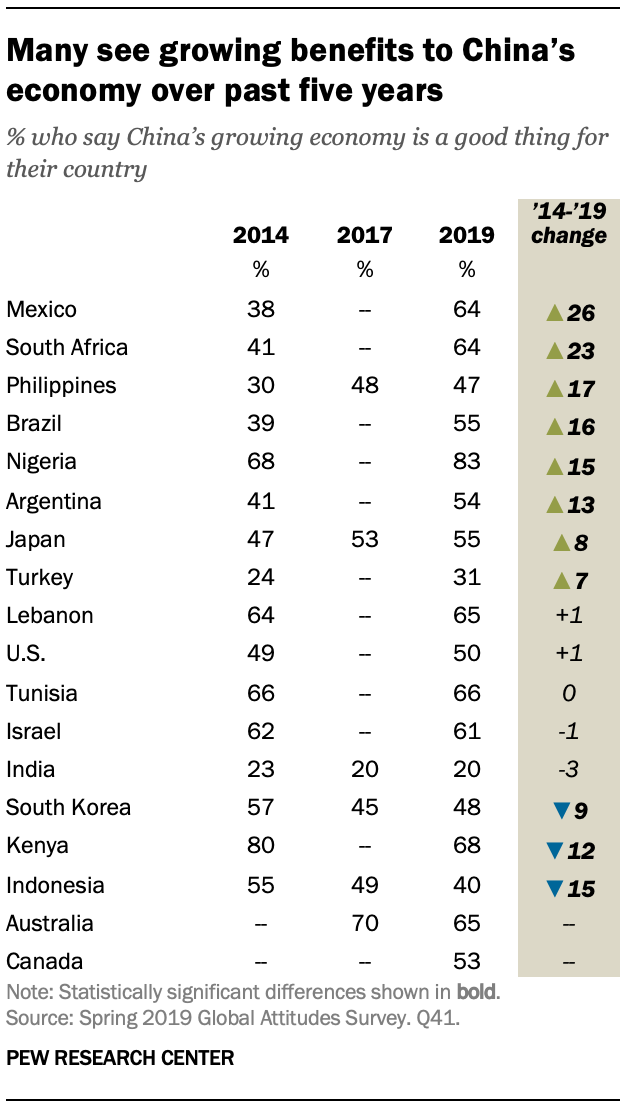

In

many emerging economies, more people today are saying China’s growing

economy is a good thing for their nation compared with five years ago.

Double-digit increases have taken place in Mexico, South Africa, the

Philippines, Brazil, Nigeria and Argentina.

In

many emerging economies, more people today are saying China’s growing

economy is a good thing for their nation compared with five years ago.

Double-digit increases have taken place in Mexico, South Africa, the

Philippines, Brazil, Nigeria and Argentina. On the other hand, South Koreans, Kenyans and Indonesians are now less likely to see benefits to China’s growing economy than they were five years ago. Still, sizable portions continue to say China’s economy benefits them in each of these three countries.

Attitudes have remained fairly steady on this question in Lebanon, the U.S., Tunisia, Israel and India.

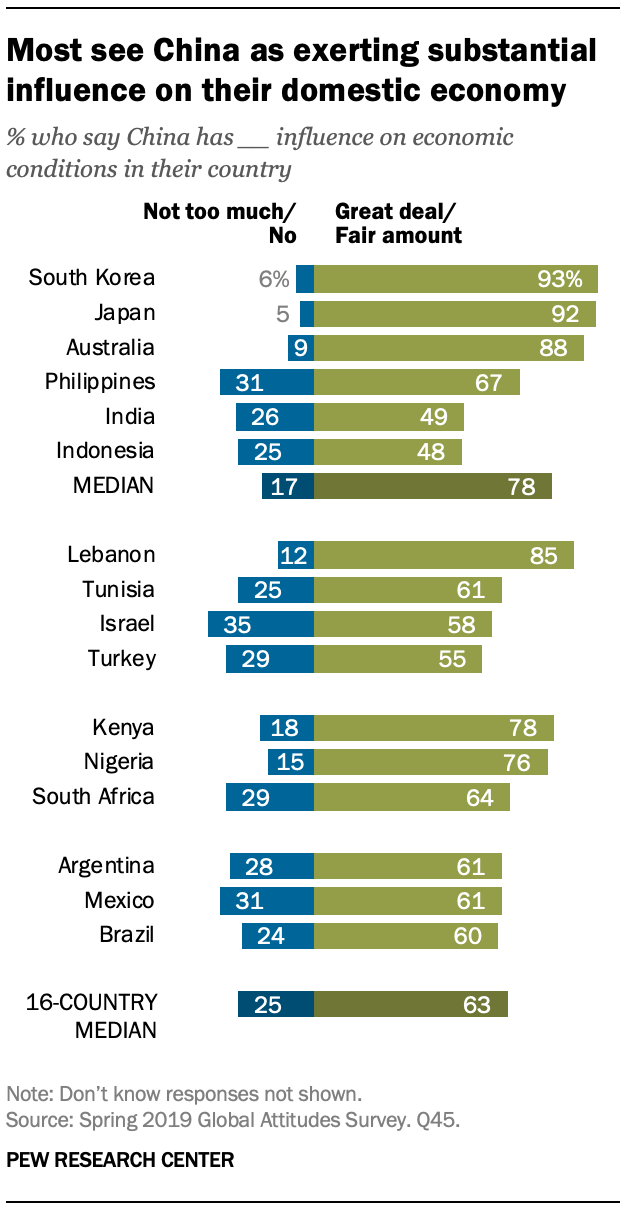

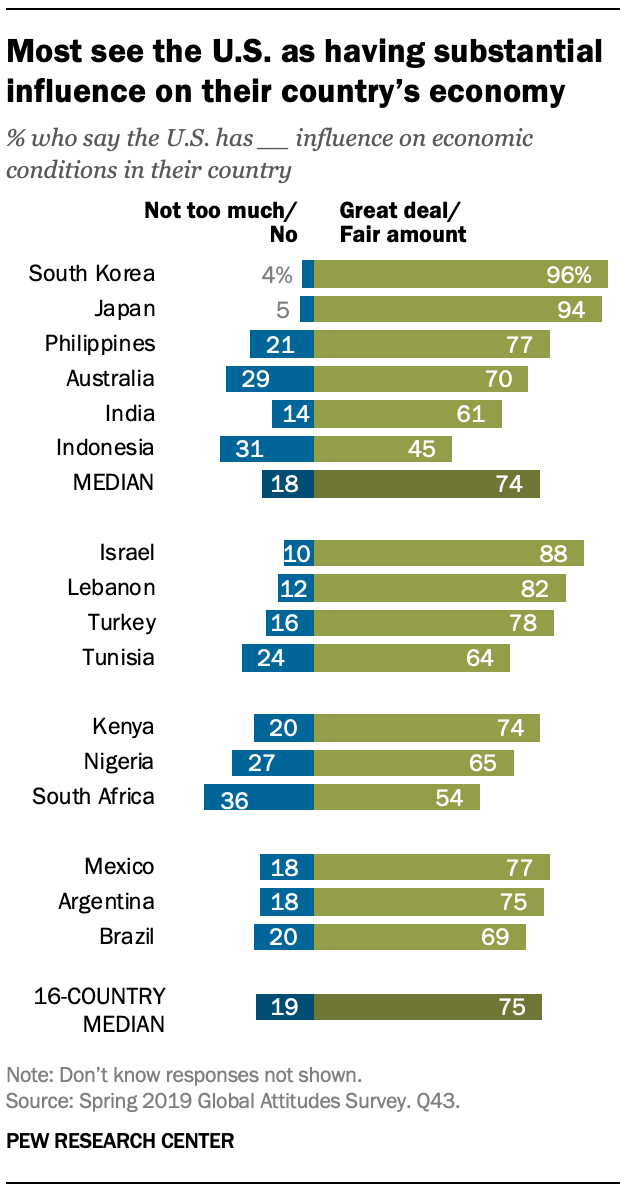

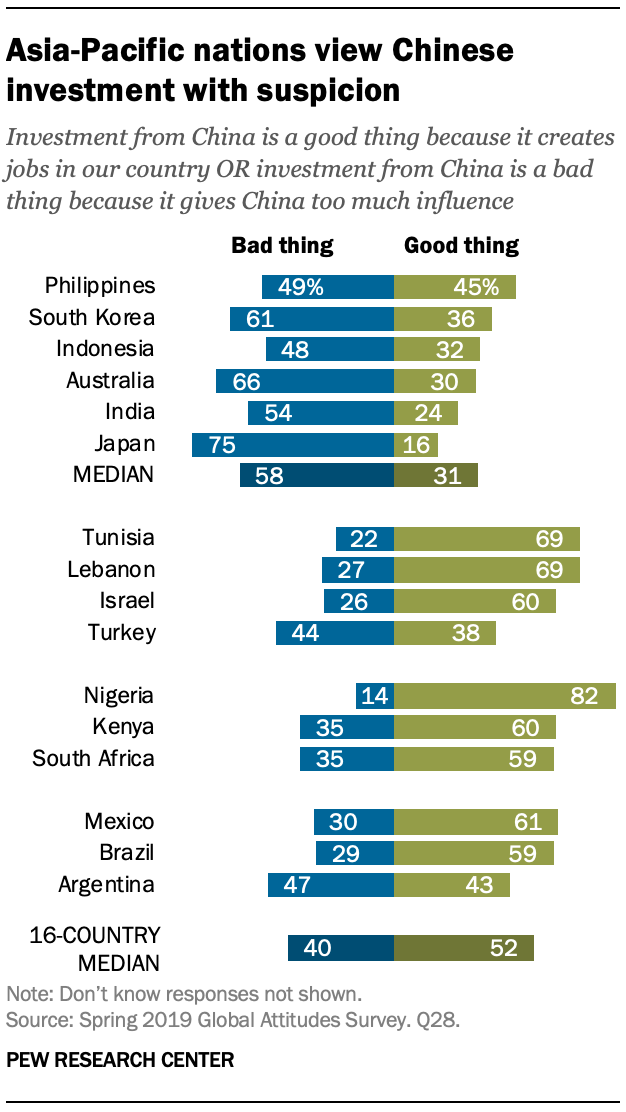

When

asked specifically about whether investment from China is good because

it creates jobs in countries or bad because it gives China too much

influence, a median of 52% regard Chinese investment as a net positive.

When

asked specifically about whether investment from China is good because

it creates jobs in countries or bad because it gives China too much

influence, a median of 52% regard Chinese investment as a net positive. Outside of the Asia-Pacific, investment from China is seen as a good thing in the receiving country. About six-in-ten or more welcome Chinese investment in Nigeria, Tunisia, Lebanon, Mexico, Israel, Kenya, South Africa and Brazil. Turkey and Argentina show more ambivalence, with no clear consensus on whether Chinese investment in their country is a good or bad thing.

Among China’s neighbors, most view investments from China with skepticism. Roughly half or more in each Asia-Pacific nation surveyed say Chinese investment is a bad thing because it gives China too much influence. This ranges from 75% of Japanese to 48% of Indonesians.

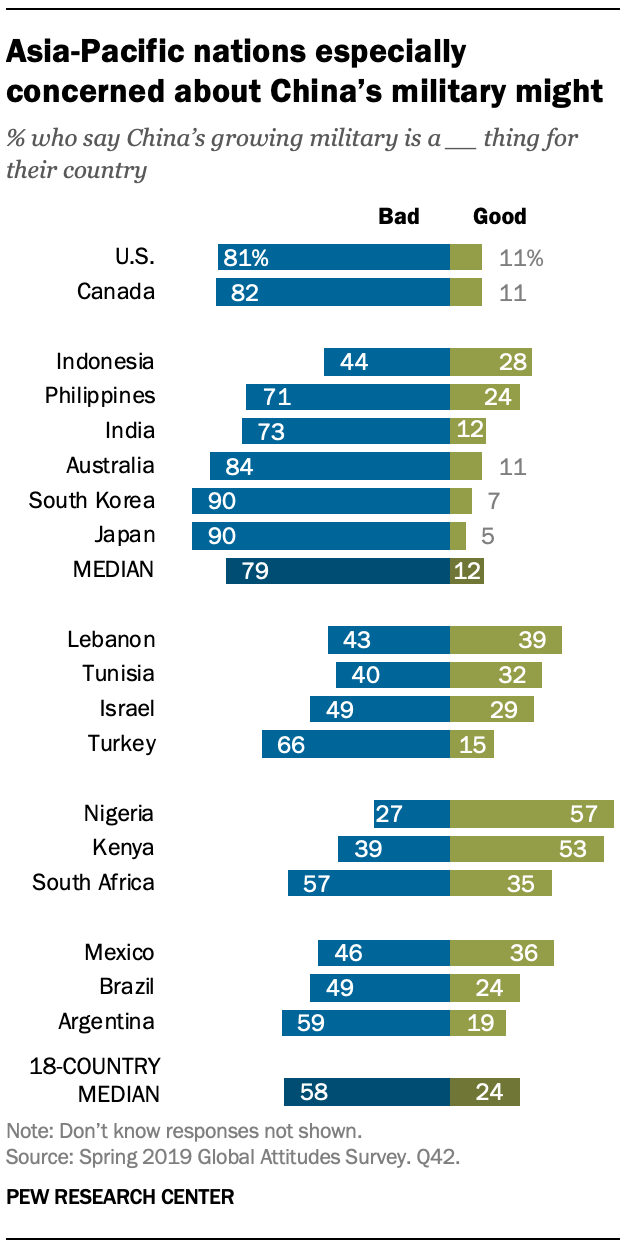

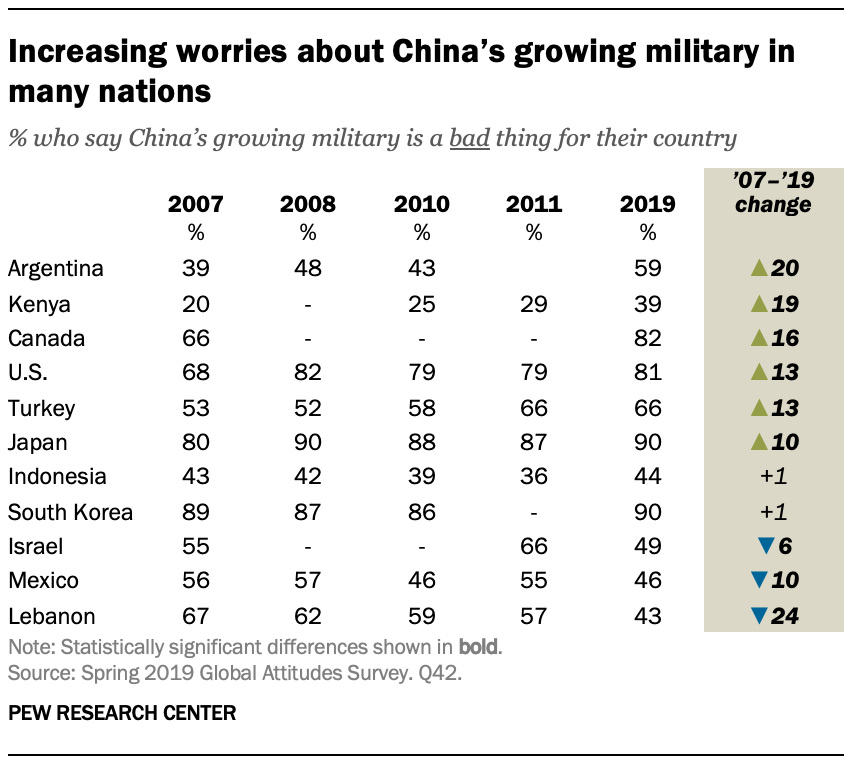

Few see China’s growing military benefiting their country

While

most countries see strong Chinese economic growth benefiting their

country, this is not the case when it comes to a growing Chinese

military. Across 18 countries, a median of 58% think increased Chinese

military strength is bad for them; 24% think this could be a good thing.

While

most countries see strong Chinese economic growth benefiting their

country, this is not the case when it comes to a growing Chinese

military. Across 18 countries, a median of 58% think increased Chinese

military strength is bad for them; 24% think this could be a good thing.

China’s Asia-Pacific neighbors are especially doubtful about the effects of a strong Chinese military on their country: Among the six countries surveyed in the region, a median of 79% say China’s growing military might is bad for their country. This is especially true in Japan and South Korea, where nine-in-ten hold this opinion.

This worry extends across the Pacific: Roughly eight-in-ten in the U.S. and Canada see China’s growing military as a bad thing for their country.

Likewise, more in Latin America and the Middle East and North Africa do not see benefits to their own nation when it comes to a growing Chinese military than do. South Africa also follows that trend. However, more than half in Nigeria and Kenya believe their country benefits from increasing Chinese military strength.

The

U.S. and Canada have become more negative about China’s growing

military since 2007. Previously, about two-thirds said the growing

military was bad, but now about eight-in-ten say so. Those in Argentina,

Kenya, Turkey and Japan have also become increasingly negative.

The

U.S. and Canada have become more negative about China’s growing

military since 2007. Previously, about two-thirds said the growing

military was bad, but now about eight-in-ten say so. Those in Argentina,

Kenya, Turkey and Japan have also become increasingly negative. On the other hand, those in Lebanon have become less negative about China’s growing military, going from 67% saying it was bad to only 43% saying it is bad. Israelis and Mexicans have similarly become less negative.

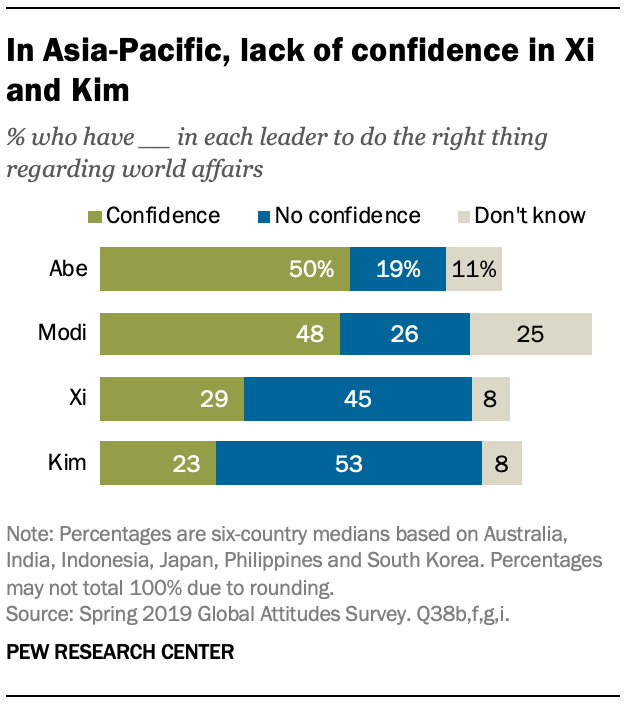

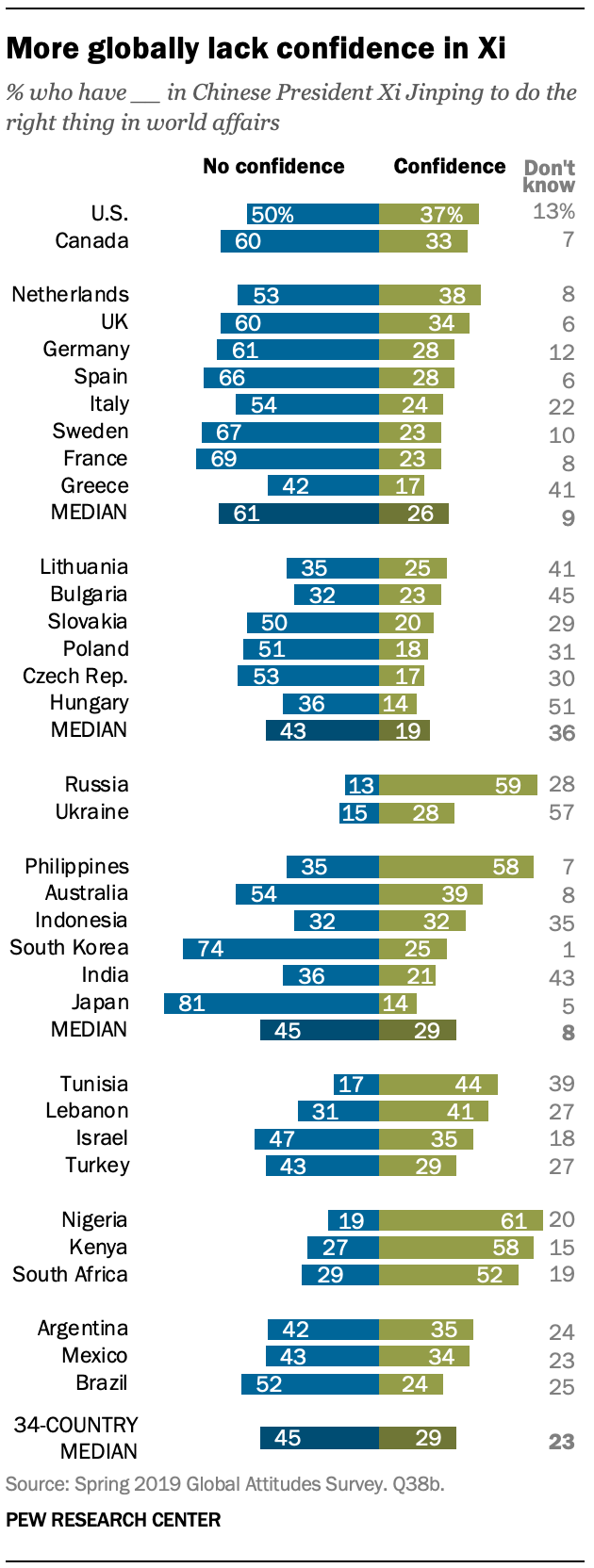

Little confidence in President Xi, particularly in neighboring countries

Views

of Chinese President Xi Jinping vary greatly across the 34 surveyed

countries, but a median of 45% say they lack confidence in the Chinese

leader when it comes to world affairs. A median of 29% voice confidence

in Xi, while 23% do not offer an opinion.

Views

of Chinese President Xi Jinping vary greatly across the 34 surveyed

countries, but a median of 45% say they lack confidence in the Chinese

leader when it comes to world affairs. A median of 29% voice confidence

in Xi, while 23% do not offer an opinion. Six-in-ten Canadians and half of Americans give negative marks to Xi. In Western Europe, a median of 61% say they lack confidence. This includes majorities in France, Sweden, Spain, Germany and the UK. While 38% in the Netherlands give Xi a vote of confidence, more than half (53%) have doubts.

Those in Central and Eastern Europe also tend to lack confidence in Xi, though he is relatively unknown across the region with more than a quarter in each country giving no opinion. Half or more in the Czech Republic, Poland and Slovakia have negative opinions of Xi. Only in Russia does Xi get positive marks, with 59% voicing confidence.

Outside of Europe, Xi’s image is more mixed. In the Asia-Pacific countries surveyed, a majority of Filipinos offer a vote of confidence in the Chinese leader. But some of China’s other neighbors are more negative, with most Japanese (81%), South Koreans (74%) and Australians (54%) saying they do not have confidence in him.

Among those who offer an opinion, more in Tunisia and Lebanon have confidence in Xi.

Israel and Turkey show the opposite pattern, with more saying they lack confidence.

Israel and Turkey show the opposite pattern, with more saying they lack confidence. About half or more in the three African countries surveyed hold positive views of Xi when it comes to world affairs. This includes 61% in Nigeria, one of China’s largest investment partners on the African continent.

Positive views of Xi have increased across several countries, both in the past year and since 2014. Significant, double-digit increases in confidence toward the Chinese leader since 2018 have occurred in Argentina, Mexico, Spain and Italy. When going back to 2014, Xi fares even better, gaining 15 points or more in the Philippines, South Africa, Argentina, Mexico, Tunisia, Russia and Nigeria.

Confidence in Xi has declined over the past year in Sweden, Hungary, Canada, Tunisia and South Korea. South Korea stands out among other countries as the only place where views of Xi have decreased significantly in both the past year and the past five years, with those saying they are confident in the Chinese leader decreasing by 32 percentage points over that period. While Tunisia shows a one-year dip, confidence in Xi is generally up since 2014.

Japanese confidence in Xi has risen since 2014, but still, only 14% of the public say they trust him to do what’s right in world affairs – the lowest level among the nations surveyed.

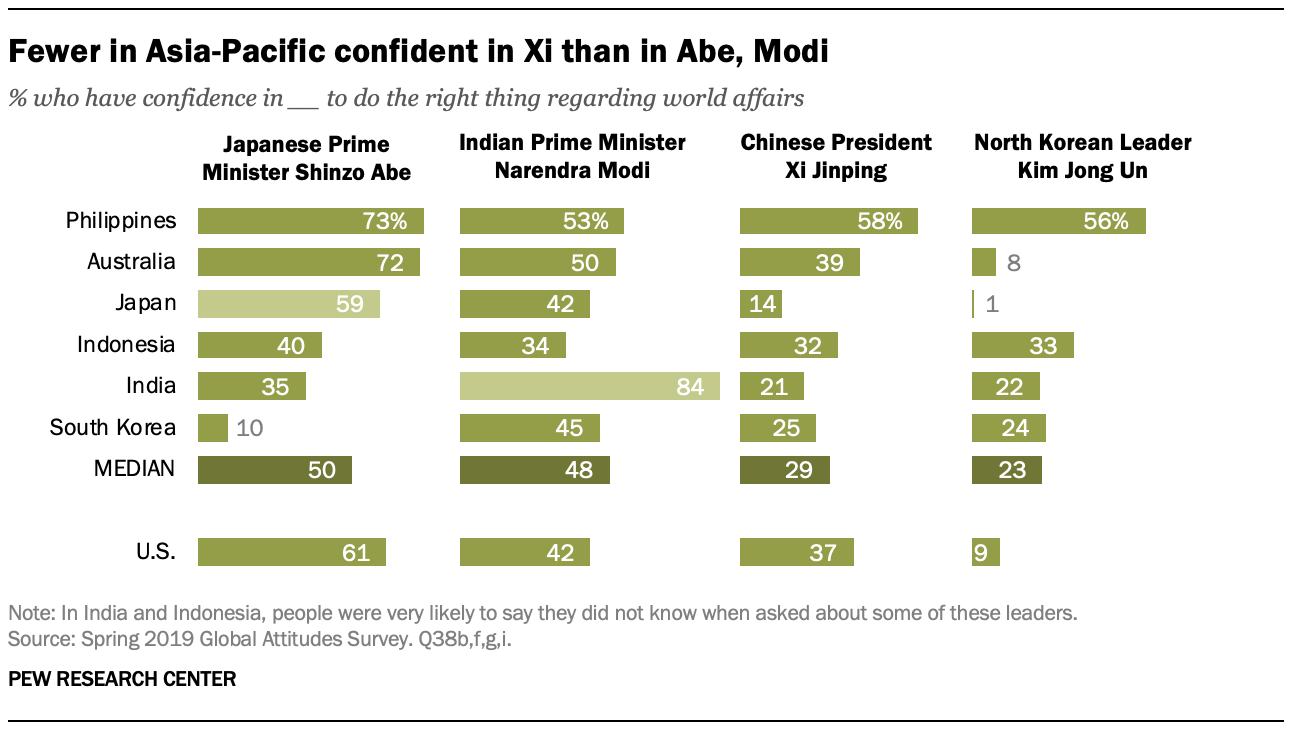

When looking at other leaders across Asia, Xi fares relatively less well among the Asia-Pacific publics surveyed. A median of 50% across these six nations have confidence in Japan’s Shinzo Abe when it comes to world affairs, and India’s Narendra Modi is close behind with 48%. Xi trails them with 29% confidence, though he beats out North Korea’s Kim Jong Un, who garners a median of 23% confidence. Filipinos stand out for their enthusiasm toward Xi: 58% have confidence in the Chinese leader.

In India and Indonesia, though, Xi’s notoriety remains limited; upwards of a third in each country do not offer a response when asked about him (or, indeed, when asked about any Asian leader with the exception of Prime Minister Modi in India). But, on balance, more in India lack confidence in Xi (36% no confidence vs. 21% confidence, 43% don’t know), and Indonesians are evenly split (32% no confidence, 32% confidence, 35% don’t know).

Fewer Americans voice confidence in Xi than say the same of leaders from other Asian nations, including Abe (61% confidence) and Modi (42% – though a third of Americans offer no opinion). However, many more think Xi will do the right thing regarding world affairs than North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, in whom a mere 9% of Americans have confidence.

Rubén Weinsteiner