Why liberal policy savants deplore rule by the people

© Lindsay Ballant

© Lindsay BallantTHE

LIBERAL INTELLIGENTSIA HAS MET THE ENEMY, and it is you. As the

shockwaves of Donald Trump’s presidency continue to shudder through our

institutions of elite consensus, a myopic, profoundly self-serving

narrative is taking shape across the politically minded academy: the

rude, irrational, dangerously xenophobic and racist rites of popular

sovereignty have swamped the orderly operations of constitutional

government. What’s more, this upsurge in mass political entitlement

isn’t confined to America’s notoriously demotic, chaotic political

culture. No, the democratic world at large is succumbing to the darker

siren songs of human nature, elevating authoritarian strongman leaders,

dusting off ugly and divisive nationalist slogans, and hastily erecting

trade barriers in the desperate, misguided hope of restoring some

mythic, nostalgia-steeped, ethno-nationalist gemeinschaft

The

name for these distressing, backward-reeling political trends, our

liberal solons agree, is populism. The hallmarks of populist movements,

we’re instructed, involve the rampant scapegoating of racial, religious

or ethnic minorities, and the fierce rejection of mediating institutions

seen to obstruct the popular will—or, in a pinch, the will of this or

that Great Leader. The resulting, chilling political dispensation works

out to an elegant sort of strongman syllogism, in the view of Harvard

government professor Yascha Mounk:

First, populists claim, an

honest leader—one who shares the pure outlook of the people and is

willing to fight on their behalf—needs to win high office. And second,

once this honest leader is in charge, he needs to abolish the

institutional roadblocks that might stop him from carrying out the will

of the people.

And once these populist goons ascend to power, all

bets are off when it comes to preserving the cherished canons of

liberal democracy. They cavalierly pack courts, suppress independent

media, and defy the separation of powers—all in the name of you, the

people. The populists now storming the world historical stage “are

deeply illiberal,” Mounk writes. “Unlike traditional politicians, they

openly say that neither independent institutions nor individual rights

should dampen the people’s voice.”

To be sure, the present world

order doesn’t lack for strongmen, hustlers, and bigoted scoundrels of

all stripes, from Donald Trump and Viktor Orban to Recep Erdogan and

Nigel Farage. But it’s far from clear that anything is gained

analytically from grouping this shambolic array of authoritarian souls

under the rubric of populism. Indeed, by lazily counterposing a crude

and schematic account of populist rebellion to a sober and serenely

procedural image of liberal democratic governance, Mounk and his fellow

academic scourges of new millennial populism do grievous, ahistorical

injury to populist politics and liberal governing traditions alike.

Let’s survey the damage in order, starting with an abbreviated look at

the history of modern populism, chiefly as it took shape here, where

it’s been most influential, in the United States.

Enmity for the People

Ever

since the dismal heyday of Joseph McCarthy, liberal intellectuals have

adopted populism as an all-purpose synonym for cynical, bottom-feeding

demagoguery, particularly when it takes on a racist or nativist guise.

McCarthy himself was undoubtedly a populist in this version of

historical inquiry, as were his many spittle-flecked progeny in the

postwar world, such as George Wallace, Pat Buchanan, and Ross Perot. For

that matter, the preceding generation of opportunist panderers outside

the political mainstream were populists as well: the FDR-baiting radio

preacher Charles Coughlin and the quasi-socialist Bayou kingmaker Huey

Long; the definitely socialist Upton Sinclair and a motley array of

Southern Dixiecrats and Klan sympathizers—populists all, and dangerous

augurs of how minority rights, civic respect, and other core

liberal-democratic values can be deformed in the hands of charismatic,

divisive sloganeers.

The only trouble with this brand of

populist-baiting is that it’s ideologically and historically incoherent.

Inconveniently for the prim, hectoring postwar sermons of populist

scourges like Richard Hofstadter and J.L. Talmon, populism originated

not as a readymade platform for strongman demagogues, but as an economic

insurgency of dispossessed farmers and working people. America’s first

(upper-case P) Populist dissenters didn’t set out to traduce and

jettison democratic norms and traditions; they sought, rather, to adapt

and expand them, in order to meet the unprecedented rise of a new

industrial labor regime and the consolidation of monopoly capitalism in

the producers’ republic they described as the “cooperative

commonwealth.”

Far from rallying to this or that fire-breathing

strongman orator, the Populists of the late nineteenth century summoned

their political insurgency out of a vast network of

purchasing-and-marketing cooperatives, known as the National Farmers’

Alliance and Industrial Union—a movement that would come to employ more

than forty-thousand lecturers nationwide and organize at the precinct

level in forty-three states. Because the Farmers’ Alliance sought to

promote both the economic independence and civic education of its

members, it began life as an urgent campaign of political pedagogy. The

pages of its widely circulated newspaper, the National Economist,

outlined the history of democratic government in the West, harking back

to Aristotle and Polybius. Alliance lecturers also found themselves

advancing not merely political literacy, but literacy itself, since the

gruesome exploitation of Southern tenantry usually involved getting

farmers to sign usurious contracts they were unable to read.

In

time, Populist organizers came to realize that simple economic

cooperation would never, by itself, countermand the kind of economic

power accruing to Gilded Age capitalists. So they began to organize a

political arm, aimed at providing the sort of infrastructure that

economic democracy requires. In addition to advocating the kind of

procedural reforms to be taken up by a later generation of Progressive

era reformers—such as direct election of senators, legislating by

popular initiative, and public ownership of utilities—Alliance

organizers proposed an alternate currency and banking system, known as

the Subtreasury Plan. The idea behind the Subtreasury was to re-engineer

America’s currency—and thereby the American economy at large—to reward

the interests of laborers over those of capital. Economic reward would

be directly weighted to crops harvested, metals mined, and goods

manufactured, as opposed to wealth amassed and/or inherited.

Populists,

in other words, took the country’s founding promise of democratic

self-rule seriously as an economic proposition—and understood, as few

mass political movements have done before or since, how inextricable the

securing of a sustainable and independent livelihood is to the basic

functioning of democratic governance. True to the incorrigibly

procedural form of liberal political appropriation, however, the

Subtreasury Plan would survive as a rough blueprint for the introduction

of the Federal Reserve in 1914—with the significant caveat that the Fed

would serve as a subtreasury network to fortify the nation’s currency

for bankers, manufacturing moguls, and stock plungers, not ordinary

farmers and workers.

Class and the Color Line

As a

movement taking root among tenant farmers in the South and West, the

Farmers’ Alliance also began to defy a foundational taboo of the white

postbellum political order. Alliance lecturers recruited black tenant

farmers into the movement’s rank and file, and began advancing a

sustained attack on the mythology of white supremacy gleefully exploited

by the region’s planter class. This attack was halting and

culture-bound, with many lapses on the part of white Populist leaders

into patrician condescension and (at times) uglier private sentiments.

But the movement’s halting lurch toward an integrationist strategy prior

to the rise of Jim Crow segregation and voting-suppression laws

throughout the South grants a bracing view on the unsettled nature of

racial politics in the region at the height of Populist organizing.

After the Alabama Populist party adopted a plank in its 1892 platform

supporting the black franchise “so that through the means of kindness . .

. a better understanding and more satisfactory condition may exist

between the races,” a white farmer wrote to the Union Springs Herald: “I

wish to God that Uncle Sam could put bayonets around the ballot box in

the black belt on the first Monday in August so that the Negro could get

a fair vote.”

It’s not clear that anything is gained

analytically from grouping today’s shambolic array of authoritarians

under the rubric of populism.

It was also in 1892 that the

national People’s Party was founded—and soon became known as the

Populist Party in the political shorthand of the day. In their landmark

Omaha Platform, the insurgent leaders of the Populist movement declared

“that the civil war is over, and that every passion and resentment which

grew out of it must die with it, and that we must be in fact, as we are

in name, one united brotherhood of free men.” Georgia Populist lawmaker

Tom Watson, who would go on to be the party’s vice-presidential

candidate in 1896, announced that the Populists were determined to “make

lynch law odious to the people.” Addressing white and black working

Americans, he pronounced an indictment of racism that had to sound

ominous indeed for the white planter elite: “You are made to hate each

other because on that hatred is rested the keystone of the arch of

financial despotism which enslaves you both. You are deceived and

blinded that you may not see how this race antagonism perpetuates a

monetary system which beggars you both.” To black audiences, he pledged

that “if you stand up for your rights and for your manhood, if you stand

shoulder to shoulder with us in this fight,” then Populist allies “will

wipe out the color line and put every man on his citizenship

irrespective of color.”

This is not to say that Populists, in

launching such salvos against the battlements of racist identity in the

South, were remotely successful. Indeed, Watson himself, having seen

conservative Bourbon forces cynically marshal black voting support

behind segregation platforms in repeated election cycles, would go on to

become a hateful paranoiac bigot in the mold of other racist Southern

demagogues. C. Vann Woodward chronicles this hideous transformation in

his biography Tom Watson: Agrarian Rebel, which stands eighty years on

as one of the most heartbreaking and unflinching studies of an American

political career ever published.

Watson’s career is also

significant because, in the hands of Richard Hofstadter’s revisionist

portrait of Populists in his 1955 book The Age of Reform, figures such

as Watson—in his late-career moral dotage—are made to stand in for the

entire Populist movement. By selectively quoting the outbursts of Watson

and other bigoted Populist orators, Hofstadter veers right by the

Alliance’s legacy of mass political education and financial reform, and

depicts the Populists as nothing more than a downwardly mobile

assortment of racist and xenophobic cranks. What ailed these unhinged

souls, Hofstadter argued, was a condition he diagnosed as “status

anxiety”—together with other demented reveries arising from their own

terminally waning cultural prestige. Without Populists, the clear

implication of his argument runs, you’d never have the whole backward,

bigoted spectacle of the modern Southern regime of racial apartheid,

hellbent on subverting any movement toward black self-rule in the name

of a sainted white Protestant Populist tradition.

Here’s the

thing, though: the institutionalized system of postbellum white

supremacy in the South came in response to the threat of the

cross-racial class alliances that Populists sought to build—not as an

outgrowth of any pre-existing bigotries on the part of Populist leaders.

Hofstadter and his many latter-day epigones like Yascha Mounk get the

causation here precisely backwards—and in the process, misdiagnose just

how and why the regime of Jim Crow took hold so deeply in the American

South. It’s not that the Populists were losing status in the South after

Reconstruction had been dismantled; it’s that they were gaining

political power on an explicit platform of cross-racial solidarity to

combat the market forces that were dispossessing poor white and black

tenant farmers alike. Given how readily Northern liberals and

Progressives of the era adapted to the reign of Jim Crow and endorsed

its racist underpinnings, it’s curious—though, alas, not surprising—to

see how populism has become the byword of choice for racist demagoguery

in respectable liberal debate.

By 1896—nearly two decades after

the Alliance’s emergence out of the earlier agrarian Grange

movement—national Populist leaders agreed to fuse with the Democratic

ticket, which nominated the free-silver boy orator from Nebraska,

William Jennings Bryan, for president.

Bryan’s thunderous “Cross

of Gold” nomination speech at the 1896 Democratic Convention served in

the popular imagination to anoint the idea of (small-p) populism as an

emotional exercise in high-voltage speechifying. But as Lawrence Goodwyn

made clear in his masterful 1976 history of the movement, Democratic

Promise (a work that neither Yascha Mounk nor any of today’s other

name-brand populism-baiters has apparently bothered to consult), the

radical, grassroots phase of Populist organizing had crested four years

prior to the 1896 fusion ticket—and while Bryan was undoubtedly a breath

of fresh air in the economically reactionary Democratic Party of Grover

Cleveland, his free-silver crusade was but a faint shadow of Populist

reform. Free Silverites had assumed national leadership of the party via

the financial support of Western mining interests keen to see the

United States go off the gold standard—and so what had been an ambitious

bid to realign the entire orientation of the nation’s political economy

became dumbed down into the sort of money-driven shadowplay all too

familiar to students of major party politics: via the alchemy of

campaign cash, the domesticated hobby horse of a cherished set of donors

becomes tricked out into the spontaneous expression of the popular

will. Free-silver was no more likely to deliver long-term prosperity to

the toiling masses than today’s Republican tax-cutting boondoggles do

(particularly since the price of gold declined shortly after the

election in the wake of newly discovered global reserves, easing

financial pressure on debt-burdened farmers and industrial workers). And

yet there it was, marketed as the panacea of first resort to the many

economic and political derangements of Gilded Age capitalism. The

Populist insurgency was likely always doomed to fail at the national

level, but to have it fail in such an inert, compromised form was a

gratuitously cruel body blow to the Alliance-aligned side of the

movement. In this light, it was somehow fitting that Bryan would end his

long public career as a fundamentalist crank and a Florida real estate

tout-for-hire at the height of the 1920s stock market boom.

© Lindsay Ballant

© Lindsay BallantSystem of a Down

All

this bears revisiting in such detail because today’s anti-populist

writers have shown themselves to be every bit as ignorant of Populist

political economy, and its richly instructive course in American

history, as Hofstadter had proven to be back in 1955. Far from

addressing the real scourges of economic privilege, the populism of

liberal lore is, as Hofstadter taught, first and foremost a movement of

ugly and intolerant cultural reaction. Even a writer like UC Berkeley

economist Barry Eichengreen, who manages to descry legitimate economic

grievances in today’s political revolt against neoliberal orthodoxy,

delivers up this magisterially nonsensical gloss on the immediate legacy

of Bryan: “Whether William Jennings Bryan is properly viewed as a

populist is disputed . . . since Bryan, while positioning himself as

anti-elite, did not prominently exhibit the authoritarian and nativist

tendencies of classic populism.”

To begin with the least risible

part first: there was of course no such thing as “classic populism” at

the time of Bryan’s elevation to the Populist-Democratic presidential

ticket, since the Populists had only emerged as a national political

force four years earlier. Not even FM radio franchises or cable

art-house channels throw around “classic” with such militant

indifference to the word’s actual meaning. But more damning, of course,

is Eichengreen’s casual ascription of authoritarian and nativist

sentiments as the essence of American populism—a tic everywhere on

display in the contemporary liberal effort to diagnose the baneful

spread of populism across the globe. The Populist movement is here

indicted for helping to originate the very apartheid system of class

rule that, as the historical record plainly shows, it had originally

sworn to dismantle; to claim that Populist figures are by definition

sowers of racial resentment is a bit like reading the modern GOP’s

full-frontal assaults on voting rights back into the historical record

to proclaim the Republicans as the party of the Confederacy.

The

late-Populist descent into race-baiting is instead better understood as

the embittered, tail-chasing phase of moral inquiry that awaits all too

many disappointed reformers in our Kabukified two-party political scene.

To hold these excrescences of Populist failure forth as first-order

definitions of populist political leadership is more than sloppy

scholarship; it’s an interested falsification of the past, directly in

line with the discredited Hofstadter school of drive-by populist

caricature.

And alas, Eichengreen is only getting started; the

unsupportable generalizations billow on and on. Ticking off the alleged

anti-democratic, “antisystem” perils of contemporary “populist”

movements, he rears back and delivers this word-picture:

Because

populism as a social theory defines the people as unitary and their

interests as homogeneous, populists are temperamentally impatient with

the deliberations of pluralist democracy, insofar as this gives voice to

diverse viewpoints and seeks to balance the interests of different

groups. Since the people are defined in opposition to racial, religious,

and ethnic minorities, populists are intolerant of institutions that

protect minority rights. To the extent that populism as a political

style emphasizes forceful leadership, it comes with a natural

inclination toward autocratic, even authoritarian rule.

No, no,

and again no. Far from displaying a telltale impatience with the

protocols of representative democracy and the delicate balancing of

“diverse viewpoints,” the People’s Party of the 1890s sought to

expandsuch deliberations and such political participation, at a time of

virulent white racism and class privilege in every other sanctum of

American political leadership. Eichengreen doesn’t say much about

alleged populist hostility toward minority rights and the populist

masses’ swooning predilection for authoritarian leaders, but none of his

sympathetic readers will much expect him to. As is the case in all

these tracts, it’s sufficient to name check a few global strongmen, a

Hugo Chavez here, a Marine Le Pen or Nigel Farage there, and the specter

of intolerant strongman populists on the march across the globe is

effectively conjured, in much the same way that saying “Candyman” in

front of the mirror three times will cause a bug-filled supernatural

predator to materialize out of thin air.

This procedure is the

globally minded academics’ version of one of the pet talking points

favored among lazy pundits during the 2016 presidential primaries:

Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders both appear to champion the cause of

forgotten citizens in the face of corrupt and self-dealing political

establishments, ergo, they must be the same kind of troublemaking

rebel!Never mind that Trump’s substantive platform departed radically

from Sanders’s governing plan in nearly every particular, from health

care provision to foreign policy to marginal tax rates; no, the notion

of a shared populist birthright binding the Queens-bred Prince Hal

figure of Trump and the Brooklyn-bred movement socialist Sanders was

simply too irresistible to pundits weaned on a historical frame of

reference that lasts about as long as your average cable commercial

break.

Brexit Ghost

In the same way, liberal political

savants are now marketing a one-size-fits-all explanation of the

spreading mood of disenchantment with the Eurozone and globalizing

capital more generally, the challenges of immigrant assimilation, the

rise of tech monopoly and the decline of social mobility and fairly

rewarded wage labor. In the brisk, mansplaining chronicles of Mounk,

Eichengreen, et al., current uprisings now get reflexively written off

to the irrational forces of mystic, metastasizing global populism, and

all the thorny, substantive questions of policy and political persuasion

that might otherwise be marshaled to address each in its turn likewise

get swept under the general heading of populist reaction. Among other

things, this interpretive schema is a bizarre brand of political

fatalism, offering little more in the way of concrete remedy to these

challenges to neoliberal governance than a prayerful hope that the

misguided souls making up the base of global “populism” will return

spontaneously to their appointed roles as rational, norms-abiding

endorsers of the neoliberal status quo.

To get some rough idea of

this procedure’s intellectual bankruptcy, consider the 2016 Brexit

vote. Here was, yes, a brashly nativist campaign to roll back the

Eurozone—but by all accounts the pitch that put the Leave vote over the

top was Nigel Farage’s canny though deeply dishonest argument that

exiting the Euro would free up vast sums of money for Britain’s national

health service. In other words, the would-be “populist” merchants of

invidious ethnic, racial, and cultural division were egged on to victory

by an appeal to continue funding at a lavish level . . . the most

successful social-democratic model of universal health care provision in

the industrialized West. Yes, there was no small amount of Leave-camp

agitprop targeting immigrant populations as a drain on the NHS’s

resources and quality of care—but the fact remains that no one, after a

decade-plus of senseless austerity cuts to the British social safety

net, was down for even a right-wing culture crusade that might reduce

health care expenditures. Indeed, the Yes campaign prevailed in no small

part by latching on to NHS spending as a badge of British cultural

identity, which might itself suggest a fertile brand of forward-looking

organizing for leftists and social democrats possessed with a scintilla

of imagination.

In lieu of any such analysis, Eichengreen dotes

on the higher rates of unemployment and the lower rates of support for

“multiculturalism and social liberalism” in the Leave camp. This is, in

part, fair enough—and as an economist, Eichengreen is properly attuned

to larger economic forces at play behind shifts in popular opinion. At

the same time, though, there’s no clear historical basis to contend, as

he does, that the downwardly mobile makeup of Leave supporters is in

line with “other instances of populism,” which plainly “suggest that an

incumbent group will react most violently—that its members will be most

inclined to feel that their core values are threatened—when they are

falling behind economically.” That is, at most, just half the picture in

any “instance of populism”—or in any broad economic mandate put before a

popular vote, which is, in reality, what was up for discussion in the

Brexit campaign. As the NHS part of the Brexit campaign made all too

plain, aggrieved Leave voters were upset about more than declining

incomes, immigrant demands on social services, and the putative excesses

of multiculturalism: they intensely disliked the legacies of

neoliberalism, as Labour and Conservative governments alike have

packaged and promoted them over the past three decades.

Second Time Farage

Indeed,

there is no more potent symbol of neoliberal governance and its many

social-democratic blindspots than the EU itself, which all but commanded

the bankruptcy of the Greek economy and denied Greece’s leftist Syriza

party functional control over the nation’s own currency so as to the

bolster the EU’s own preferred terms of maximum austerity in the

comically misnamed Greek bailout. Yet it’s easy to forget in postmortems

like Eichengreen’s that membership in the EU was precisely the question

at stake in the Brexit vote. Eichengreen does cite the sluggish

performance of the British economy in the wake of its admission to the

EU, but notes in a bizarre footnote that, among the “big three”

continental economies of France, Germany, and the UK, the fact “that

[economic growth] decelerated by less in Britain suggests the EU

membership and Thatcher-era reforms had a positive effect.” That would

be in the same sense, one supposes, that it’s a “positive effect” to be

kicked in the shins rather than strangled from behind.

Eichengreen

puzzles over why issues of inequality loomed larger over the Brexit

ballot than they had during the retrograde policy reign of Margaret

Thatcher. He notes greater maldistribution of per capita income in

Britain as opposed to other major EU member nations and briefly

references the disastrous austerity-driven response to the 2008 meltdown

orchestrated by the Cameron government. Still, it’s principally the

familiar Hofstadter specter of “status anxiety” and tribally fomented

economic nationalism that drive Eichengreen’s anatomy of the Brexit

campaign—so much so that he depicts Tony Blair’s vastly liberalized

immigration policy at the EU’s behest not as an inflection point in the

consolidation of labor markets under the aegis of global capitalism, but

rather as the natural continuation of the market revolution ushered in

under Thatcher. England had already, by the late 1990s, been taking in a

greater share of its population growth from former UK colonies than it

had through natural biological increase—with new immigrants mostly from

former colonial holdings of the former British empire. But, Eichengreen

notes:

This changed . . . with Tony Blair’s decision in 2004

to allow unrestricted access to the U.K. labor market for citizens of

the EU’s eight new Central and Eastern European member states. The U.K.

labor market was tight, and Blair had the backing of business. The

policy was part of his strategy to reposition the Labour Party as

business friendly and pro-globalization. The decision to open the doors

to the new EU8 was, in fact, part of a broader set of government

initiatives that included also more permits and visas for young people

seeking work in the tourist trade and for seasonal agriculture

The

reason that wages for all workers have been stagnant for so very long

is that our predatory managerial and owning classes have kept the vast

share of economic gains in this country for themselves.

Put

another way: after Margaret Thatcher spent the better part of a

generation cutting the once-robust British union movement off at its

knees, Tony Blair pledged his fealty to global capital by casualizing

his country’s low-wage service economy. But Eichengreen, in spite of his

own economic bona fides, dismisses any class-based animus in the

backlash to the immigration wave that followed hard upon Blair’s

decision. EU8 immigrants were comparatively better educated than their

forerunners in the former British colonial sphere and so couldn’t be

seen as a threat to low-skilled, native-born job holders, he argues—and

besides, “the foreign-born share and the proportion of a region’s voters

supporting Leave were in fact negatively correlated. It’s as if regions

where knowledge of immigrants was least, fear of immigration was

greatest.”

Here we are again, in other words, in the reassuring

liberal world of declining cultural status. Populists are nativists by

definition, and nativists are hostile to immigration because they simply

don’t know any better; they live in regions where the presence of a

smattering of immigrants is likely to be more upsetting or disorienting

than in higher-density outposts of the global knowledge economy. It’s

hard not to note the affinities here between Eichengreen’s culturally

determinist gloss on the Brexit outcome and Hillary Clinton’s principal

alibi for her 2016 election defeat: that Democratic voters are

clustered, via their own assortative genius, in places that “are

optimistic, diverse, dynamic, moving forward,” while the sad-sack,

downwardly mobile Trump base “was looking backwards” in its Ghost-Dance

style mission to make America great again.

Meanwhile,

Eichengreen’s other telltale metric of populist distemper—the

weak-at-the-knees reaction to strongman leaders retailing sagas of

cultural restoration—is quite comically absent from the Brexit

referendum and its aftermath. Nigel Farage was a C-list media

personality prior to the Brexit vote and now resides much further back

in the celebrity alphabet. Theresa May nearly lost a heretofore

ironclad-seeming Conservative majority by trying to jerryrig an early

vote on her party’s Leave agenda, while mop-topped demagogue Boris

Johnson, the former mayor of London, was driven into premature

private-sector retirement by the sheer political unworkability of any

and all Brexit plans presently on the books.

Norms Follow Function

So

again: if these omniscient accounts of the latter-day scourge of global

populism aren’t actually about populism, what are they about? Well,

they’re doing what neoliberal intellectual work has been doing for the

better part of a generation now—making the logic of market-driven policy

appear to be a species of the highest political wisdom. This mission is

at the heart of Mounk’s puzzlingly influential book, which tilts again

and again at straw-man avatars of the “populist” menace in order to

confirm what he and his cohort of think-tank apparatchiks knew all

along: that the expert-administered dictates of the neoliberal market

order are not simply the optimal arrangements for global capitalist

enterprise; they are also, and far more urgently, the last, best hope

for rescuing our fragile, Trump-battered democratic norms from the

populist abyss. It’s right there in the book’s subtitle: Why Our Freedom

Is in Danger and How to Save It.

However, on closer inspection,

the task of saving our freedom isn’t a call to the barricades, the town

hall, or the picket line; it is, rather, a closely modulated accord

among postideological elites to keep all currents of opinion within

their appointed lines. This pronounced and insular vision of elite

governance for its own sake explains why Mounk and other self-appointed

prophets of the gathering populist storm consistently fail to highlight

what is in fact a central, and deeply anti-populist, bulwark of

conservative rule over the past generation—the activist right’s militant

embrace of state-based voter suppression, which has no remote

historical affinity with a movement devoted to the expansion of the

franchise via direct election of senators, legislation by initiative,

and preliminary challenges to racist disenfranchisement of postbellum

black voters. Astonishingly, Mounk devotes a section of his book to

bemoaning the decline of judicial review in Western democracies without

coming to grips with the substantive impact of the Roberts Court’s

irresponsible gutting of the enforcement of the Voting Rights Act, and

the staggeringly counter-empirical Trumpist obsession with the threat of

race-based “voter fraud.” Then again, such first-order assaults on

basic democratic participation at the grassroots level have no clear

place in a tract devoted to what Mounk is pleased to call “the

miraculous transubstantiation between elite control and popular appeal.”

It

gets worse. Highlighting the penchant of strongman demagogues to

translate power relations into conspiracy theories, Mounk surreally

argues that the best rejoinder to such unhinged public reveries is “to

re-establish traditional forms of good government.” And the way to do

this, it turns out, is to bow once more before the well-worn

governmental shibboleths of the neoliberal information age:

To

regain the trust of the population once Trump leaves office,

politicians will have to stick to the truth in their campaigns; avoid

the perception of a conflict of interest; and be transparent about their

dealings with lobbyists at home and government officials abroad.

Politicians and journalists in countries where norms have not eroded to

the same degree should, meanwhile, double down with renewed zeal: As the

American case shows, such norms can erode frighteningly quickly—and

with terrible consequences.

After Trump won the 2016

election, Barack and Michelle Obama were mocked in some quarters for

having insisted throughout the campaign that “when they go low, we go

high.” It is, of course, easy to mock a team that continues to play by

the rules when the opposing team turns up with goons in tow and clubs in

their hands. But for anyone who wishes to keep playing the game, it’s

not clear what the alternative is: if both sides take up arms, its

nature changes irrevocably. Unlikely as it might seem at the moment, the

only realistic solution to the crisis in government accountability (and

most likely the larger crisis in democratic norms) is therefore a

negotiated settlement in which both sides agree to disarm.

It’s

hard to conjure a better rhetorical example of high-church proceduralism

in the neoliberal age. There’s the notion that the excesses of Trumpism

can be effectively dispelled by the self-policing moral rehabilitation

of our leadership caste, as opposed to any expansion of

political-economic freedoms that an aggrieved citizenry might demand on

their own behalf. There’s the fanciful notion that Democrats blew the

2016 election by “going high” and adopting a morally superior campaign

rhetoric, when in point of fact the Clinton campaign devoted its final

general election push to a blizzard of harsh negative attacks on

Trump—in part because even at that late date, Clinton couldn’t give a

clear account of why she wanted to be president beyond it being the next

logical entry on her resume. (Anyone who thinks “going high” is second

nature to Hillary Clinton in campaign mode clearly slumbered through the

2008 primary season, when she and her surrogates mounted an

unrelentingly vicious counteroffensive against her upstart opponent

Obama.) Finally, there’s the broader depiction of political discourse as

a formalist byplay of norms upheld by force of liberal leadership—norms

that are at once the bedrock foundation of responsible public inquiry

and yet somehow also prone to instantaneous collapse once a billionaire

pseudo-populist and his retinue of goons start whaling away on them.

This

ritualized fetish of norms and rules is but the extension of the habits

of mind exemplified by Davos-style neoliberalism into the sphere of

political morality. The notion that representative democracy best

expresses itself in formalist modes of compromise and mutual disarmament

is the mode of agreement best disposed to bargaining parties whose own

social power is assured and ratified well beforehand. The formalist

dream of government exclusively by rules and norms is a minuet among

privileged arbiters of polite conduct who can afford the luxury of

believing they are “going high” by deigning to enter the public sphere

in the first place. All that’s missing here is a ritual call for greater

“civility” among the surly ranks of Trump resisters—but Mounk completed

his manuscript before that procedural plaint became de rigueur among

right-thinking liberals.

Keep in mind, too, that Mounk lays out

his proceduralist playbook of elite deference as the best response to

the plague of conspiracy thinking on the “populist” left and right. Why,

if you simply increase your transparency, the reasoning goes, your

virtues will become self-evident—as though conspiracy-mongering has

overtaken our common world only because we’ve all needed a firmer

pedagogic hand at our social-media cursors. Among other things, this

sunnily didactic view of truthful-leadership-by-example overlooks the

Obama administration’s commitments to official secrecy, leak

prosecutions, and extralegal drone assaults of all description, despite

its frequent rhetorical invocations of its own exemplary commitments to

“transparency” and plain-dealing. It’s hard to see, in other words, how

assurances of improved probity coming from our leadership class would be

greeted with anything other than a chorus of disbelieving guffaws—or

why they should be.

© Lindsay Ballant

© Lindsay BallantProductivity for What?

Mounk’s

analysis grows yet more evidence-averse and saucer-eyed when he

addresses what had been the great strength of historical Populist

organizing: the condition of the political economy. He devotes much of

the discussion to the mandate to increase worker productivity, while

also asserting that “the role that inequality has played in the

stagnation of living standards has sometimes been overstated.”

Productivity gains, he insists, are the best hope for the improvement of

economic conditions across the board: “if productivity had grown at the

same rate in the past few decades as it had in the postwar era, the

average American household would now be able to spend $30,000 more per

year.”

Well, duh—the gains in both productivity and income over

the first flush of the American economy’s postwar expansion were without

precedent in human history. (This would be why French economists refer

to the three decades following World War II as the trentes glorieuse.)

But what Mounk isn’t telling his readers is that wages have failed to

keep pace even with more modest productivity increases for American

workers over the past four decades—which is why wages for those workers

have remained essentially stagnant since the mid-1970s. So if you coax

higher productivity numbers out of the U.S. wage economy as it’s

presently configured, that’s the least likely path to improving the lot

of the average worker.

But of course productivity gains are

catnip to neoliberal managers and tech entrepreneurs—the same readers

who’ve elevated Mounk’s tract into Hillbilly Elegy status for the TED

Talk circuit. So once again we’re marched through alarmist talk of the

grievous state of American public education as a training ground for

knowledge workers and the anemic state of STEM funding. Sounding for all

the world like Bill Gates cooing into Mark Zuckerberg’s ear, Mounk

announces that an “ambitious set of educational reforms is needed to

prepare citizens for the world of work they will encounter in the

digital age.” Then it’s on to true gibberish, as Mounk seeks to apply

his stunted apothegms on productivity to the world of work as it now

actually exists. Militantly ignoring the last forty years of American

wage stagnation, Mounk offers this otherworldly snapshot of what an

improved social contract for American workers might look like:

After

all, low productivity and high inequality tend to be mutually

reinforcing. Workers who have low skills don’t have much bargaining

power. This, in turn, depresses their wages, and makes it more likely

that their children will also fail to acquire sufficient skills to

succeed.

The reason that workers lack bargaining power,

regardless of their skill levels, is that most forms of union organizing

have either been outlawed or drastically curtailed under the neoliberal

economic policymaking of the past four decades. And the reason that

wages for all workers have been stagnant for so very long is that our

predatory managerial and owning classes have kept the vast share of

economic gains in this country for themselves. Latest figures from the

Economic Policy Institute show that the pay gap separating CEO salaries

from those of average workers now stands at 312 to 1.

Uber, But for Plutocrats

All

the STEM curricula and Task Rabbit apps in the world won’t set that

imbalance to right. But in lieu of a policy directive along the lines of

organize your workplaces and tax the living shit out of the wealthy,

Mounk again counsels the stately and measured trimming of differences

between workers and rapacious managers—er, excuse me, dynamic

entrepreneurs. And presto: a plan “to structure the world of work in

such a way as to make it possible for people to derive a sense of

identity and belonging from their jobs—and to remind the winners in

globalization of the links they share with their less fortunate

compatriots.” How might this staggering conceptual breakthrough be

coaxed into being? Well, let global laborcrat Yascha Mounk sketch it out

for you:

Take the example of Uber. It seems relatively clear

that governments should neither forbid the service, as some countries

in Europe are proposing, nor allow it to circumnavigate key protections

for their workforce, as most parts of the United States have effectively

done. Rather, they should steer a forward-looking middle

course—celebrating the huge increase in convenience and efficiency that

ride-sharing offers while passing new regulations which ensure that

drivers earn a living wage.

Never

mind that the entire business model of Uber is organized around the

idea of denying its casualized workers a minimum wage (the

median wageof

Uber and Lyft drivers now works out to $3.37 an hour); or that recent

studies indicate that, once vehicle maintenance and gas costs are

factored into the equation, nearly a third of Uber drivers are actually

losing money.

The larger point is that this daft “forward-looking middle course”

mimics in structure and substance alike virtually every misguided

neoliberal policy that has beggared the living conditions of workers and

debtors throughout the world, and sparked the very far-flung rebellions

against globalizing capitalism that Mounk’s book purports to describe.

With selected phrasing substitutions, this Goldilocks-style prescription

of punitively wage-starving policies might have been lifted, say, from

Al Gore’s heroic defense of the NAFTA accords while debating Ross Perot

in 1995, when the former third-party presidential candidate prophesied a

“giant sucking sound” of vanishing American jobs would follow hard on

the new trade deal. Or it could have been taken from any number of

Silicon Valley photo ops for candidate Hillary Clinton in 2016, as she

celebrated the “convenience and efficiency” of an economic sector that

doubles as both a wage-suppressing labor cartel and a libertarian cult.

Mounk’s

Third Way policy prescription also echoes an especially distressing

blindspot of neoliberal labor thinking: it’s taken for granted here that

“governments” serving undefined constituencies are the right economic

actors to be shaping the optimal labor relations for the ride-sharing

market, and not, say, drivers themselves. Never mind that New York’s

Taxi Workers Alliance managed under its own organizing steam to get the

number of app-based drivers capped in the nation’s largest market for

ride-sharing—thereby helping secure the livelihoods of a union

membership that’s seen six taxi drivers kill themselves under the

race-to-the-bottom

logic

of rampant ride-sharing. No, re-organizing your productive life in your

own interest is too hopelessly divisive, and could even prove to be

dangerously “populist” over the longer term. So just lie back and let

above-the-fray global bureaucrats manage your working lives on your

behalf, and you can thank us later.

This is, at bottom, the

vision of expert-mediated civic life that the Yascha Mounks of the world

are seeking to repackage as our imperiled tradition of “representative

democracy.” Talk about your giant sucking sounds.

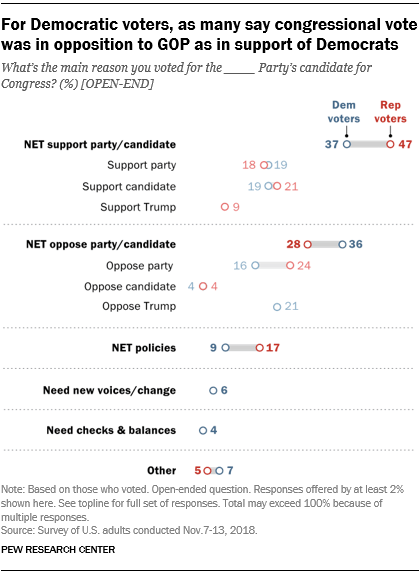

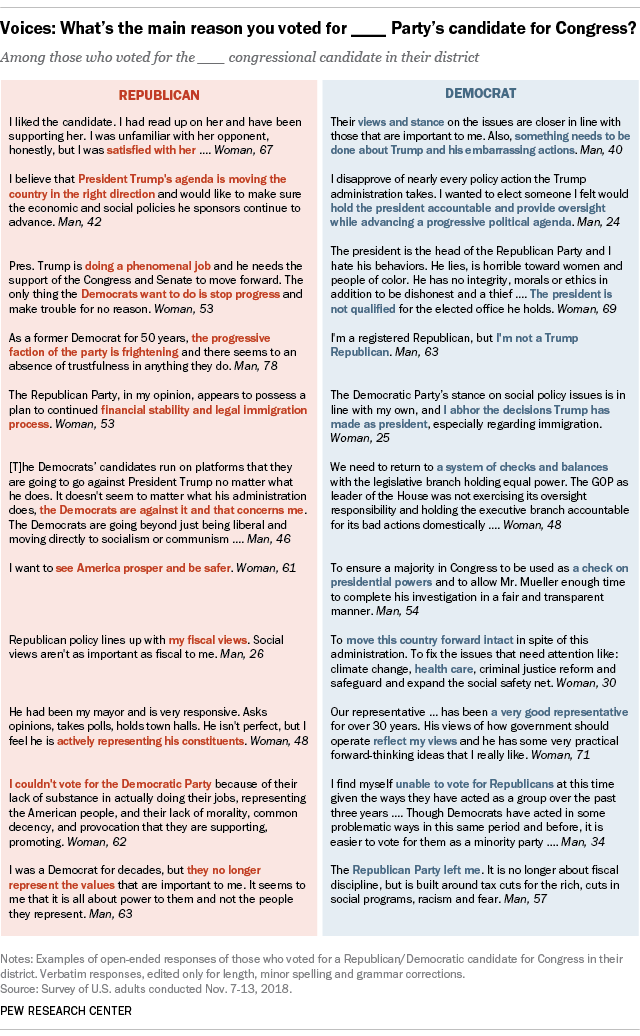

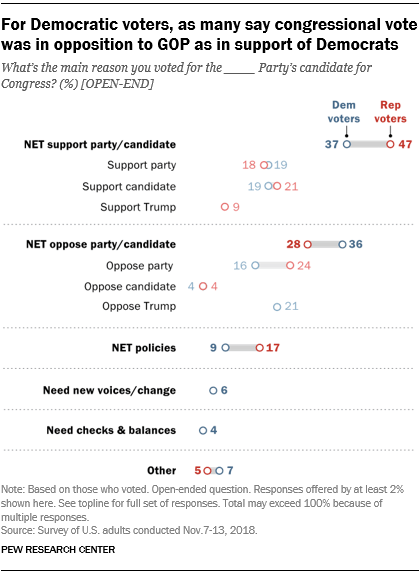

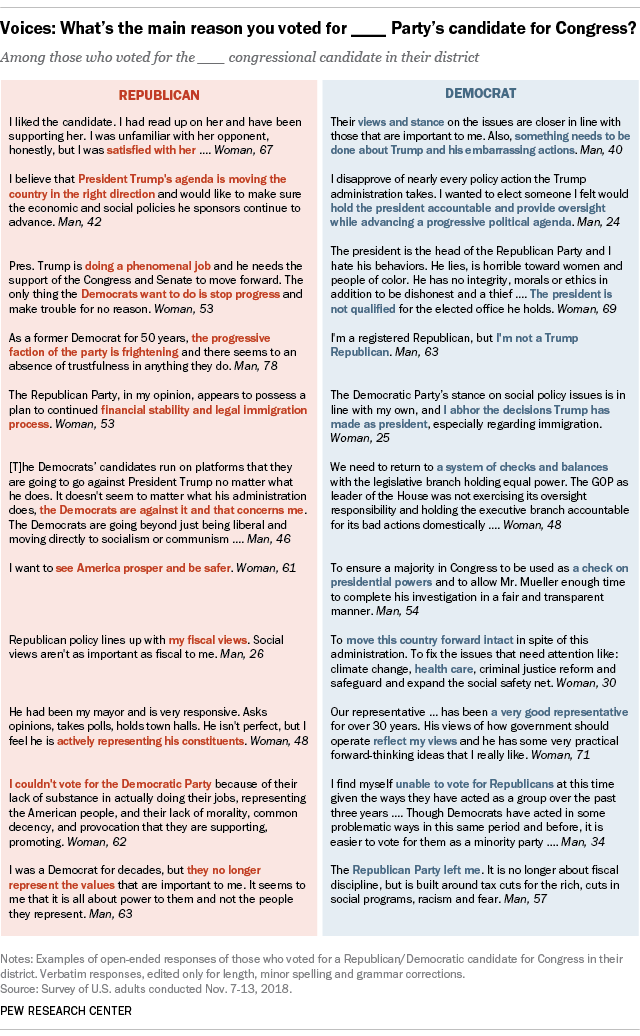

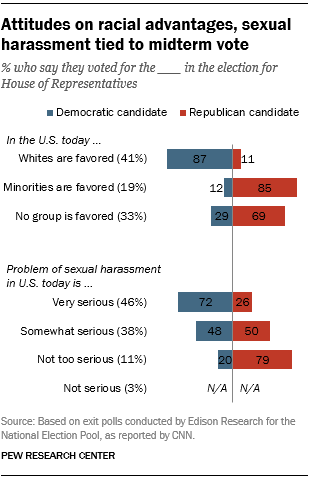

Although

partisan motivations dominated across the board, the tone of these

partisan motivations differed somewhat between Republican and Democratic

voters, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted Nov. 7-13.

Although

partisan motivations dominated across the board, the tone of these

partisan motivations differed somewhat between Republican and Democratic

voters, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted Nov. 7-13.

Although

partisan motivations dominated across the board, the tone of these

partisan motivations differed somewhat between Republican and Democratic

voters, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted Nov. 7-13.

Although

partisan motivations dominated across the board, the tone of these

partisan motivations differed somewhat between Republican and Democratic

voters, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted Nov. 7-13.

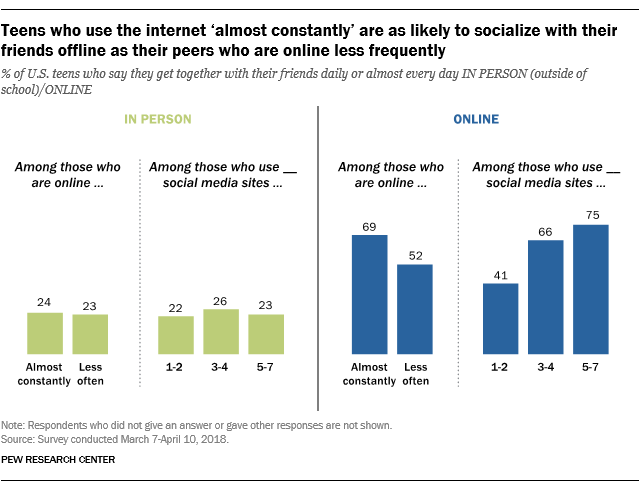

In

fact, when taking into account both online and offline interactions,

highly connected teens report more contact with their friends compared

with other teens, according to the analysis, which comes amid concerns

that screen time is

In

fact, when taking into account both online and offline interactions,

highly connected teens report more contact with their friends compared

with other teens, according to the analysis, which comes amid concerns

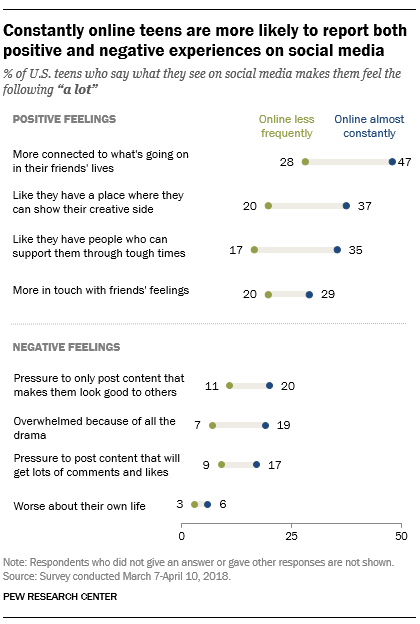

that screen time is  When

it comes to their broader attitudes toward technology, teens who go

online almost constantly see a wider range of positive effects from

social media than their peers who use the internet less frequently. For

instance, they are substantially more likely to say that social media

makes them feel a lot more connected to what’s going on in their

friends’ lives and that they have people who can support them when going

through tough times.

When

it comes to their broader attitudes toward technology, teens who go

online almost constantly see a wider range of positive effects from

social media than their peers who use the internet less frequently. For

instance, they are substantially more likely to say that social media

makes them feel a lot more connected to what’s going on in their

friends’ lives and that they have people who can support them when going

through tough times.

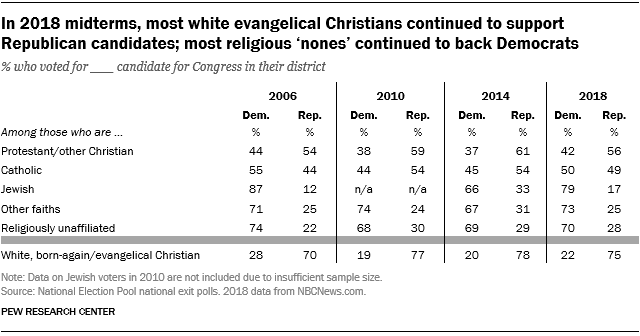

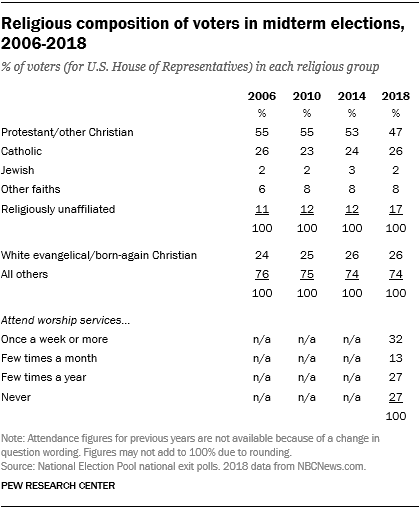

At

the other end of the spectrum, seven-in-ten religious “nones” voted for

the Democratic candidate in their congressional district, which is

virtually identical to the share of religious “nones” who voted for

Democratic candidates in 2014 and 2010. Roughly eight-in-ten Jewish

voters (79%) cast their ballots for the Democrats, higher than the share

who did so in 2014, but somewhat shy of 2006 levels. (Data on Jewish

voters were not available in 2010.)

At

the other end of the spectrum, seven-in-ten religious “nones” voted for

the Democratic candidate in their congressional district, which is

virtually identical to the share of religious “nones” who voted for

Democratic candidates in 2014 and 2010. Roughly eight-in-ten Jewish

voters (79%) cast their ballots for the Democrats, higher than the share

who did so in 2014, but somewhat shy of 2006 levels. (Data on Jewish

voters were not available in 2010.)  Among

Protestants, 56% voted for Republican congressional candidates and 42%

backed Democrats. Among those who identify with faiths other than

Christianity and Judaism (including Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus and many

others), 73% voted for Democratic congressional candidates while 25%

supported Republicans.

Among

Protestants, 56% voted for Republican congressional candidates and 42%

backed Democrats. Among those who identify with faiths other than

Christianity and Judaism (including Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus and many

others), 73% voted for Democratic congressional candidates while 25%

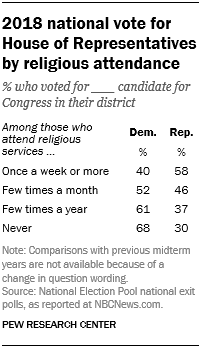

supported Republicans.  Voters

who say they attend religious services at least once a week backed

Republican candidates over Democrats in their congressional districts by

an 18-point margin. Those who attend services less often tilted in

favor of the Democratic Party, including two-thirds (68%) of those who

say they never attend worship services.

Voters

who say they attend religious services at least once a week backed

Republican candidates over Democrats in their congressional districts by

an 18-point margin. Those who attend services less often tilted in

favor of the Democratic Party, including two-thirds (68%) of those who

say they never attend worship services.

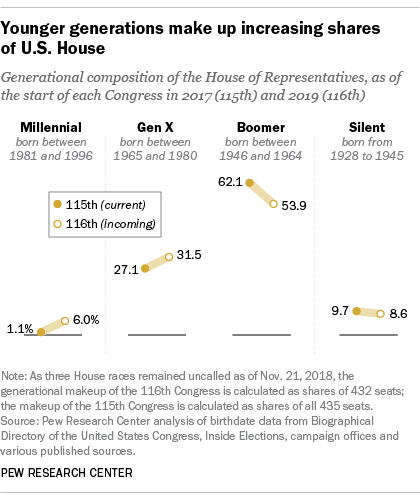

When

the 116th Congress convenes in January, at least 26 House members will

be Millennials (i.e., born between 1981 and 1996), up from only five at

the start of the current Congress in January 2017 and six just before

the Nov. 6 midterms. (Pennsylvania Democrat Conor Lamb, 34, won a

special election this past spring for a seat that had been vacated by

Tim Murphy, a Boomer; Lamb and the five other serving Millennials all

were re-elected.) More than a fifth (20) of the 91 freshmen

members-elect are Millennials, and 14 of those 20 are Democrats –

including Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, at 29 the

When

the 116th Congress convenes in January, at least 26 House members will

be Millennials (i.e., born between 1981 and 1996), up from only five at

the start of the current Congress in January 2017 and six just before

the Nov. 6 midterms. (Pennsylvania Democrat Conor Lamb, 34, won a

special election this past spring for a seat that had been vacated by

Tim Murphy, a Boomer; Lamb and the five other serving Millennials all

were re-elected.) More than a fifth (20) of the 91 freshmen

members-elect are Millennials, and 14 of those 20 are Democrats –

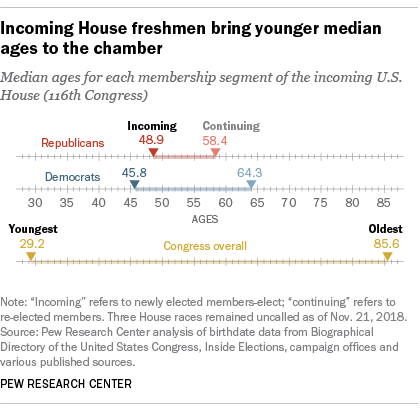

including Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, at 29 the  The age gap between continuing and new House members is widest among Democrats, a fact that’s coming into play in the

The age gap between continuing and new House members is widest among Democrats, a fact that’s coming into play in the

Incoming

Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez waits for a House of

Representatives member-elect welcome briefing on Capitol Hill in

Washington

Incoming

Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez waits for a House of

Representatives member-elect welcome briefing on Capitol Hill in

Washington

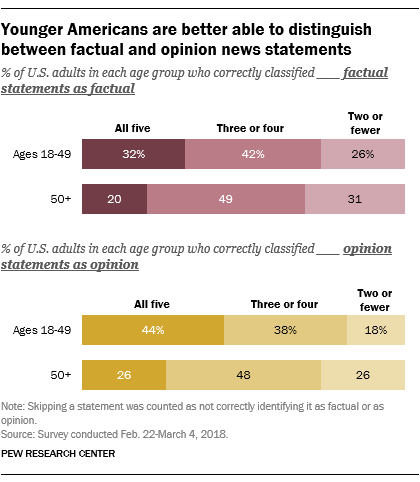

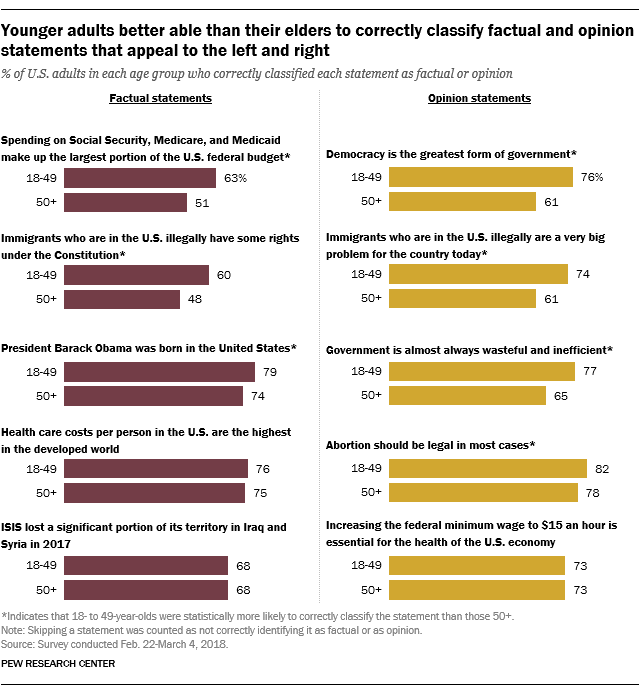

In

a survey conducted Feb. 22 to March 4, 2018, the Center asked U.S.

adults to categorize five factual statements and five opinion

statements. As a previous

In

a survey conducted Feb. 22 to March 4, 2018, the Center asked U.S.

adults to categorize five factual statements and five opinion

statements. As a previous  For

example, 63% of 18- to 49-year-olds correctly identified the following

factual statement, one which was deemed to appeal more to the right:

“Spending on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid make up the largest

portion of the U.S. federal budget.” About half of those ages 50 and

older (51%) correctly classified the same statement. Additionally, 18-

to 49-year-olds were 12 percentage points more likely than those at

least 50 years of age (60% vs. 48%, respectively) to correctly

categorize the following factual statement, which was deemed to be more

appealing to the ideological left: “Immigrants who are in the U.S.

illegally have some rights under the Constitution.”

For

example, 63% of 18- to 49-year-olds correctly identified the following

factual statement, one which was deemed to appeal more to the right:

“Spending on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid make up the largest

portion of the U.S. federal budget.” About half of those ages 50 and

older (51%) correctly classified the same statement. Additionally, 18-

to 49-year-olds were 12 percentage points more likely than those at

least 50 years of age (60% vs. 48%, respectively) to correctly

categorize the following factual statement, which was deemed to be more

appealing to the ideological left: “Immigrants who are in the U.S.

illegally have some rights under the Constitution.”

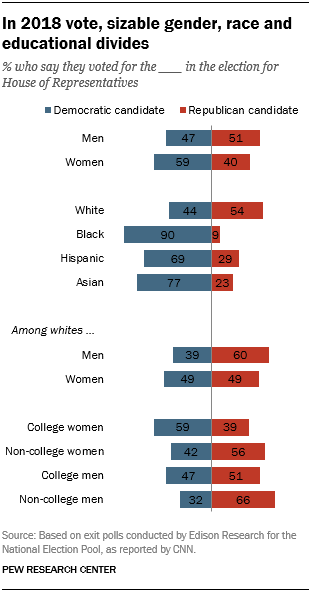

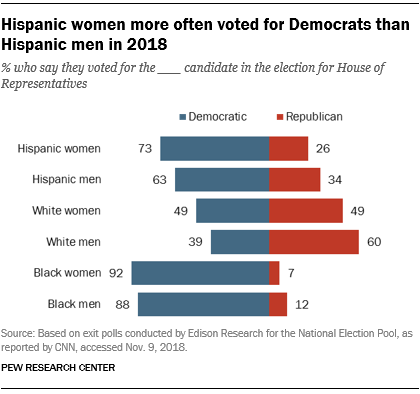

There

were wide differences in voting preferences between men and women,

whites and nonwhites, as well as people with more and less educational

attainment.

There

were wide differences in voting preferences between men and women,

whites and nonwhites, as well as people with more and less educational

attainment.  The

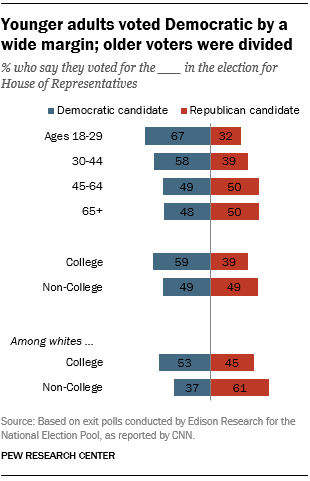

age divide in voting, which barely existed in the early 2000s, also is

large. Majorities of voters ages 18 to 29 (67%) and 30 to 44 (58%)

favored the Democratic candidate. Voters ages 45 and older were divided

(50% Republican, 49% Democrat).

The

age divide in voting, which barely existed in the early 2000s, also is

large. Majorities of voters ages 18 to 29 (67%) and 30 to 44 (58%)

favored the Democratic candidate. Voters ages 45 and older were divided

(50% Republican, 49% Democrat).  In

a year in which issues around gender and racial diversity have been key

issues in politics, voters were divided in their opinions about whether

whites or minorities are favored in the country today and whether

sexual harassment is a serious problem in the U.S.

In

a year in which issues around gender and racial diversity have been key

issues in politics, voters were divided in their opinions about whether

whites or minorities are favored in the country today and whether

sexual harassment is a serious problem in the U.S.

In

U.S. congressional races nationwide, an estimated 69% of Latinos voted

for the Democratic candidate and 29% backed the Republican candidate, a

more than two-to-one advantage for Democrats, according to National

Election Pool

In

U.S. congressional races nationwide, an estimated 69% of Latinos voted

for the Democratic candidate and 29% backed the Republican candidate, a

more than two-to-one advantage for Democrats, according to National

Election Pool  About

a quarter of Hispanics who cast a ballot in 2018 (27%) said they were

voting for the first time, compared with 18% of black voters and 12% of

white voters, according to the exit polls. Meanwhile, many new voters

this year were young.

About

a quarter of Hispanics who cast a ballot in 2018 (27%) said they were

voting for the first time, compared with 18% of black voters and 12% of

white voters, according to the exit polls. Meanwhile, many new voters

this year were young.  Hispanics

had a gender gap in voting preference, with 73% of Hispanic women and

63% of Hispanic men backing the Democratic congressional candidates – a

reflection of the election’s broad gender differences. In a pre-election

Pew Research Center survey of Hispanics, differences by gender extended

to views of the country. For example, Hispanic women were significantly

Hispanics

had a gender gap in voting preference, with 73% of Hispanic women and

63% of Hispanic men backing the Democratic congressional candidates – a

reflection of the election’s broad gender differences. In a pre-election

Pew Research Center survey of Hispanics, differences by gender extended

to views of the country. For example, Hispanic women were significantly

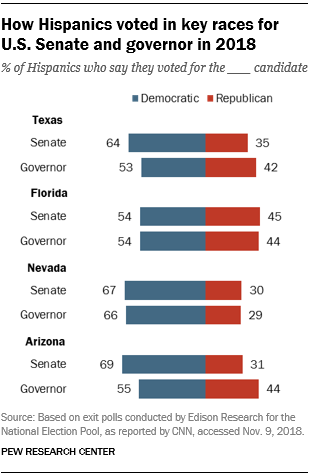

Latinos

made up a notable share of eligible voters in several states with

competitive races for U.S. Senate and governor, including Texas (30%),

Arizona (23%), Florida (20%) and Nevada (19%). In these states,

Democrats won the Latino vote, sometimes by a wide margin. In the Texas

Senate race, 64% of Latinos

Latinos

made up a notable share of eligible voters in several states with

competitive races for U.S. Senate and governor, including Texas (30%),

Arizona (23%), Florida (20%) and Nevada (19%). In these states,

Democrats won the Latino vote, sometimes by a wide margin. In the Texas

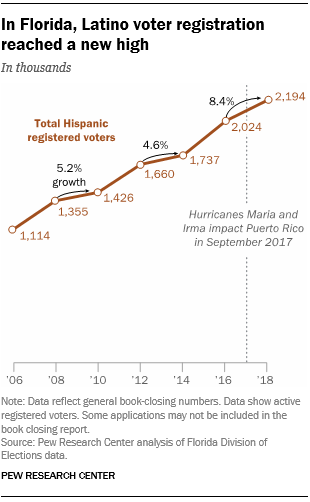

Senate race, 64% of Latinos  In

Florida, a record 2.2 million Hispanics registered to vote this year,

an 8.4% increase over 2016. This is nearly double the increase from the

previous midterm election in 2014, when Hispanic voter registration

increased 4.6% over 2012.

In

Florida, a record 2.2 million Hispanics registered to vote this year,

an 8.4% increase over 2016. This is nearly double the increase from the

previous midterm election in 2014, when Hispanic voter registration

increased 4.6% over 2012.