When can America reopen from its coronavirus shutdown? The answer

depends how you weigh human health against the economy. We asked experts

how to think about the tricky calculus.

After

days of market freefall, President Donald Trump hinted two weeks ago

that he was thinking about relaxing public-health restrictions for the

sake of the economy—“WE CANNOT LET THE CURE BE WORSE THAN THE PROBLEM

ITSELF,” he tweeted, before promptly getting roasted by the public

health world. Did he really want to sacrifice American lives to goose

the Dow back up? It seemed inhumane.

Since then, the president

has backed away from opening businesses up right away, but he also had a

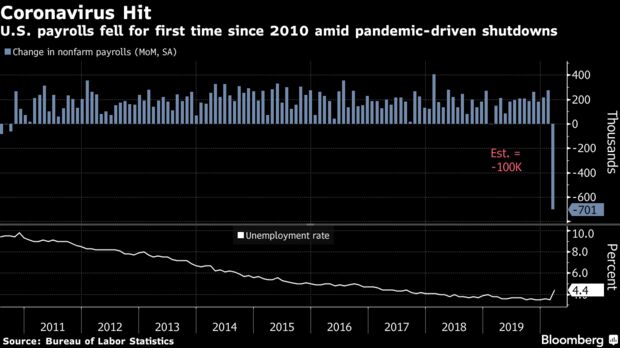

point: This cure is pretty bad. This week’s report that 6.6. million

Americans had filed for unemployment insurance was double the previous

record, which was set only last week. Analysts are predicting that GDP

could shrink by

double-digit percentages this quarter. That’s a lot of future unhappiness.

At

the same time, the disease might be even worse. Trump’s coronavirus

task force has said that 100,000 to 240,000 Americans could die from the

virus, and that’s the best-case scenario.

So, what’s the right

amount of economic pain to endure in order to save lives? The debate

will only intensify over the next month, as we approach the April 30

endpoint Trump set for national social-distancing guidelines, and

pressure builds to re-open businesses, despite the high likelihood the

virus will still be spreading.

MARCA POLITICA turned to a

handful of thinkers—people who have studied the impact of pandemics,

recessions and more—to helps us understand how to even begin to think

about the dilemma ahead. Do we really need to weigh lives against money?

If so, how do you do it right?

Spoiler alert: No one offered us

a hard date for when life will go back to normal. But there were some

surprises. You’ll find a clear guide to making the lives-money tradeoff

(and a good rationale for doing it), a surprising fact about the

economics of the response to a past global pandemic, a suggestion for a

surgical middle-ground approach to a reopening, and a strong argument

that recessions actually save lives.

1. THE COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS

2. HOW RECESSIONS AFFECT DEATH

3. WHAT THE SPANISH FLU TELLS US

4. WHAT IF THERE’S NO TRADEOFF?

5. THE QUICKEST FIX

6. MODELING THE COSTS OF SOCIAL DISTANCING

1

Why Economists Measure Human Lives in Dollars

It’s

a highly imperfect exercise—but could actually save more people. James

Broughel is a senior research fellow and Michael Kotrous is a program

manager with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

It

might feel heartless when President Donald Trump muses about whether the

“cure is worse than the problem,” as though a plunging stock market and

a patchwork of business and travel shutdowns could possibly outweigh

the lives saved by America’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic. And it

might feel uncomfortable to think about the response as a tradeoff

between saving the economy and saving lives.

But we really are

facing that tradeoff, and, in fact, economists make a routine practice

of comparing dollars with lives. There are costs and benefits to every

policy decision, and by valuing human lives in dollar terms we can

arrive at a way to measure those costs and benefits against each other.

As

human beings, we tend to see life as having almost infinite value, but

it’s also worth remembering that money spent to save one life has an

opportunity cost: It could have been spent in another fashion and—if

spent more efficiently—saved even more lives. Resources are never

unlimited, and without assessing the dollars-to-lives tradeoff, it’s

likely that policymakers will fail to save as many lives as they

otherwise could.

When it comes to policy, and especially an

urgent and life-altering policy issue like the current epidemic, the

problem with this kind of cost-benefit calculation isn’t in the idea,

it’s in the execution. Even for run-of-the-mill policies, it’s tricky to

assess whether a policy does more good than harm. With respect to

Covid-19, an exhaustive cost-benefit analysis is even harder because of

limitations in our ability to track the disease’s spread, predict the

human response to it and analyze the effects that policy will have in

slowing its transmission.

Acknowledging these challenges, here’s what the numbers look like, as best we can determine.

On

the cost side of the ledger, it is difficult to disentangle the costs

of the shutdown policy from the costs of the coronavirus itself. Many of

Trump’s supporters talk as though the economy would fully re-open if

the restrictions were lifted. But even if governors around the country

lifted their emergency orders overnight, would life return to normal,

and the stock market revive fully? Likely not. There would still be a

new and dangerous virus in the country. Aside from the thousands, maybe

millions, who became sick, many more people would still stay home while

the risk of infection remains high.

To get a handle on the costs

of current policies, one must identify the elusive “counterfactual”

scenario—what would happen if the government did nothing. If we assume

that most people would choose to stay home regardless of any government

action, then the costs of government orders to stay inside and close

businesses could be close to zero. At the other extreme, Federal Reserve

analysts have estimated that GDP could decline by as much as

50 percent

in the second quarter of this year. If we assume that it’s really

government orders driving this behavior, and otherwise people would be

going about their business, then the cumulative cost of the government’s

response is vast, as much as $2.5 trillion just in this quarter. The

cost over the long-term would be even higher.

The true cost

likely falls somewhere in between these extremes. The debate in Congress

about the proper amount of stimulus might be instructive. One way to

look at the $2 trillion stimulus package passed last week is as an

attempt by the government to make Americans whole for the costs of being

forced to stay home by government orders. Provisions of the stimulus

bill directly address these costs—increasing unemployment benefits and

broadening eligibility for

millions of recently unemployed Americans, as well as loan and grant programs that may allow small businesses to make payroll during the shutdown.

Then there is the benefits side of the ledger, which is also difficult to gauge. A

study

from Imperial College London estimated that as many as 2.2 million

Americans might die as a result of Covid-19, but this was an early

estimate that basically assumes

no behavioral responses

from the public as the disease devastates the country. Even if we

assume that number is a reasonable upper limit on how many people might

die, there’s still the question of how effective government policy will

be in changing the trajectory of the pandemic’s progression and saving

lives. Some epidemiologists believe that as soon as the social

distancing efforts end, the virus will return with a vengeance.

Here’s

where assigning a dollar value to life-extending benefits enters the

equation. One common way to do this is by using the “value of a

statistical life,” or VSL, which reflects what current citizens are

willing to pay to reduce their own risk of death. (It’s usually

estimated by looking at how much extra compensation workers in dangerous

professions get paid.) Estimates of the VSL vary, but tend to average

about

$10 million

for Americans. If we assume, for example, that the government’s

response to Covid-19 prevents an enormous death toll of 2 million

citizens, the value of all those prevented deaths could be as much as

$20 trillion.

However, the value of a statistical life is not

universally accepted by economists. For one thing, what an individual is

willing to pay to reduce risk might be very different from what society

should pay. A person nearing the end of life might find it rational to

expend all of his or her wealth on potential life-extending treatments.

But society, which will endure past any of our individual lives, ought

to be more frugal with its finite resources.

An alternative

approach to the VSL is to consider the productive contributions

associated with extending life—that is, the economic value people are

expected to contribute. Such an approach is commonly employed when

valuing the benefits of regulations that enhance our health. For

example, an environmental policy that prevents asthma attacks or

non-life-threatening illnesses might end up saving society money by

reducing hospital stays or emergency room visits. Compared with the VSL,

this approach provides more of an apples-to-apples comparison between

benefits and financial costs. It accepts that the true value of a life

is likely undefined, but we are at least able to estimate the economic

value each person creates.

One

2009 study

estimated the total value of worker production at different stages of

life, including the value of “nonmarket” roles such as staying at home

to raise kids. The authors estimated that the present value of future

worker contributions ranged from about $91,000 to $1.2 million in 2007,

depending on the age of the worker.

Age is an important factor in the coronavirus pandemic, too. The CDC has

reported

that, as of March 16, 80 percent of U.S. deaths from Covid-19 have been

people ages 65 or older. Combining the CDC’s numbers with the

aforementioned estimates of the value of worker production at various

ages (and updating them for rising productivity and inflation since

2007), we end up with an expected value of forgone earnings for victims

of Covid-19 of about $414,000 per person. Even this estimate of

benefits—already drastically lower than the VSL at $10 million—likely

overestimates the economic value of workers in cases when the cost of

replacing them is relatively low.

In other words, the economic

benefit of preventing all those potential deaths depends on which

controversial measure you use: In this case, upper-bound estimates of

mortality benefits associated with government interventions range

between $20 trillion with the VSL approach and $828 billion if the

worker production approach is extended to 2 million lives saved. Twenty

trillion dollars is roughly the value of an entire year of the nation’s

GDP; $828 billion is considerably less than the value of Congress’

latest economic stimulus bill.

There are other costs and benefits to account for as well. On the one hand, a prolonged shutdown of the economy could

increase

some health risks for those who lose their jobs, a knock-on cost of

impoverishing so much of the citizenry. On the other hand, Covid-19 has

been shown to cause significant

lung damage

among some of those who recover; reducing those cases is another

potential benefit of government action. An economic shutdown could even

have unexpected benefits—for example, a decrease in air pollution or the

number of car crashes.

To go strictly by the numbers, Trump may

well be right that the government “cure”—in the form of restrictions on

commerce and movement—might be worse than the Covid-19 disease. But

it’s also possible, given what we know, that everything the government

is currently doing is worth it, and relatively inexpensive to boot.

Cost-benefit

analysis can offer us a way to think about decisions, and put some

boundaries around the likely outcomes. But even in simpler

circumstances, it cannot always provide bright-line recommendations. And

it can’t answer our deepest and most profound questions. In some cases,

the calculus has to be driven not by a set of numbers, but by our

values.

2

Social Distancing Saves Lives. So Do Recessions.

If

you’re weighing a recession versus a pandemic in terms of lives lost,

there’s no contest. Contrary to popular belief, deaths go down during

economic downturns.

Anne Case and Angus Deaton are economists at Princeton University. They are the authors of the recently published book

Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism.

When Donald Trump

tweeted

in late March, “WE CANNOT LET THE CURE BE WORSE THAN THE PROBLEM

ITSELF,” a lot of people had questions about what “worse than the

problem” meant, exactly. “You’re going to lose more people by putting a

country into a massive recession or depression,” he clarified a few days

later in a Fox News town hall. “You’re going to lose people. You’re

going to have suicides by the thousands.”

The assumption that

people die more in recessions feels right, and so it seems like a good

reason to suggest risking a more severe coronavirus outbreak with

lighter restrictions on businesses and people, instead of inviting the

worst economic crisis since the 1930s. There are, after all, a lot of

reasons to imagine such a surge in deaths could happen: lost healthcare

due to lost jobs, which would make people more vulnerable to otherwise

preventable deaths and, of course, suicides.

But the assumption

that people die more during recessions is wrong, at least in wealthy

countries. Past economic downturns show that, in fact, mortality rates

go down in recessions, for a number of reasons. If you’re weighing the

human cost of a recession or depression against the human cost of

illness and death from the virus itself, as Trump and policymakers

across the country are doing right now, it’s important to keep in mind

that the toll of a recession in terms of lives lost is not a factor.

It’s

true that poor people die younger. That was true in France and Britain

in the 19th century, and it is true in the United States today. People

in their mid-40s in the top 1 percent of tax returns have about

15 more years

to live than people in the bottom 1 percent. Yet is it not true that

when people get poorer, they are more likely to die; annual death rates

are lower in recession years than in boom years.

In our recent book,

Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism,

we argue that the long-term, 70-year, slow-motion collapse of work,

wages and community for working-class Americans is the root cause of the

epidemic of drug overdose, suicide and alcoholism that has ravaged

less-educated men and women. That epidemic, and those deaths, came after

a slow and prolonged decline in the wages and jobs that supported

working-class life—very different from the normal upswings and

downswings of the business cycle. Despair came over years and decades,

not from a short-term downturn in the economy.

One of the

first studies

of health and recession was published almost a century ago by

sociologists William Ogburn and Dorothy Thomas (the first woman to be

tenured at the Wharton School). They made the important distinction

between “lasting changes in the economic order”—such as the Industrial

Revolution or, to extend to our own work, the erosion of working-class

life that underlies deaths of despair—and “brief swings in economic

prosperity and depression, around the line of general economic trends,”

such as the Great Depression.

They examined booms and busts from

1870 to 1920 and found, to their own astonishment, that death rates

rose in good times and fell in bad times. They were careful not to

overstate their findings—“we do not draw a definite conclusion”—so

strong was the seemingly obvious presumption that bad times bring death.

That presumption is widely held to this day.

One might think

the pattern of recessions and death from a century ago is different from

today. A century ago, pneumonia, influenza and tuberculosis were the

leading causes of death, not cancer and heart disease. Deaths were

“younger,” with death rates among infants higher than death rates among

the elderly, the inverse of today’s pattern. Sixteen out of every 100

children did not live to see their first birthdays.

But the same pattern of recessions and deaths held throughout the 20th century. Mortality rates

fell

from 1930-33, the four worst years of the Great Depression; in the

1920s and 1930s, mortality rates were highest in the years of fastest

economic growth. The same

was true

for the longer period from 1900 to 1996. Business cycles differ to some

extent in different U.S. states, and mortality was lower in bad times

state by state in the 1970s and 1980s. The same was true in

England and Wales

for economic fluctuations from 1840 to 2000. The relationship was

stronger at some times than at others, but the pattern was consistent:

Mortality declined more rapidly in bad times, and declined more slowly

or even rose in good times. Europe and

Japan show the same pattern.

What

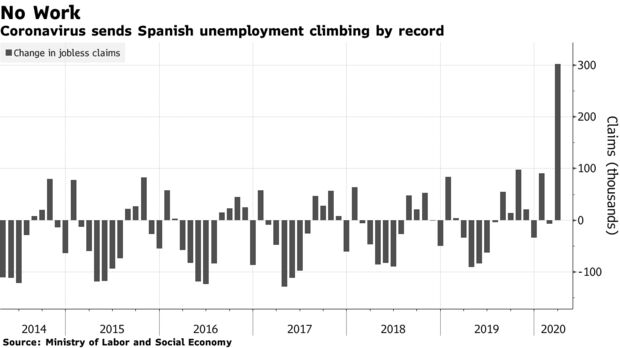

about the Great Recession after the financial crash in 2008? The

economic effects were most severe in a few European countries, like

Spain and Greece. Remember Greece? Its economy was so devastated that it

threatened to crash out of the Eurozone. In the United States, it was

used as the bogeyman, the perennial warning of what might happen to us

if we did not get our fiscal house in order. Unemployment in Greece and

Spain more than tripled, to the point where more than a quarter of the

population was unemployed. Yet Greece and Spain saw

increases in life expectancy that were among the best in Europe.

For

the Great Recession in the United States, the story is more

complicated, because the years after 2008 saw a large and growing

epidemic of deaths of despair. But deaths of despair began to rise in

the early 1990s and grew inexorably into the 2010s. They rose before the

Great Recession, and grew during and after the Great Recession; the

line of rising deaths shows

no perceptible effect of the collapse of the economy.

The big question is: Why? And why is our intuition so wrong?

Many

of us have the haunting vision of ruined financiers hurling themselves

out of skyscrapers and off of bridges during the great crash of 1929.

These accounts were doubtless exaggerated, but suicides did indeed

increase during the subsequent Great Depression. Suicides, however, are

the exception, not the rule, and they are a small share of total deaths.

In 2018, there were 2.8 million deaths in the United States, of which

48,000 were suicides—less than 2 percent of the total. Each is a

tragedy, but it takes very large changes in suicides before the suicide

tail wags the mortality dog.

Why might the non-suicide deaths decline in recessions? High activity rates bring dangers. There are

more traffic accidents. There are more

occupational accidents when construction is booming and factories are running at full tilt. There is more

pollution,

a life-threatening danger for some infants. It is also possible that

busier lives bring stress, and that stress brings heart attacks. Or that

people have less time for exercise, healthy meals and self-care. In

today’s rich economies, most deaths are among the elderly, and many

older people are cared for by low-wage workers. When the economy is

booming, when there are better paid jobs elsewhere, it is much

harder to hire and retain these workers for nursing and elder-care homes. Care matters.

Which

brings us back to suicides. Because suicides usually do rise in

recessions, we think that there is a plausible case that the forthcoming

recession will bring more suicides. But not inevitably.

Mass layoffs from

plant closures

have often brought suicides in their wake. Today, people are losing

their businesses; workers and owners whose livelihoods and lives are

structured and given meaning by what they have created—restaurants and

coffee shops, bookstores, small businesses and non-profits of all

stripes—may reasonably fear that they will never reopen, even if

government packages provide some relief. They may feel shame that they

did not make provision for such a calamity, shame unlikely to be shared

by the managers of corporations who used their profits not to build a

rainy day fund, but to buy back shares that enriched themselves and

their shareholders, knowing that they would be bailed out in a

catastrophe.

This recession, unlike others, involves social

distancing or, for many and increasingly more as infection rates rise,

isolation. Social isolation is a classic correlate of suicide. The

United States has a suicide “belt” that runs north-south along the Rocky

Mountains where population density is low. New Jersey, where we live

most of the year, has the lowest suicide rate in the country; Montana,

where we spend August, has the highest. Zooming in, Madison County,

Montana, has a suicide rate that is four times higher than that of

Mercer County, New Jersey. Isolation and depression can be deadly.

Think, too, of the millions of people in recovery programs, like

Alcoholics Anonymous, whose sobriety depends on community support.

Social distancing will also bring more suicides this time around if

hospitals are slow to respond, so that more attempted suicides may

succeed.

Yet there is an important counterargument. Suicides tend to be low in

wartime,

especially when leaders can build social solidarity, the opposite of

social isolation. Winston Churchill inspired the British in World War

II. Governor Andrew Cuomo is inspiring New Yorkers (and many other

Americans) who listen to his broadcasts. If the rhetoric of fighting the

common enemy wins out against the possibility that Americans are

jobless, alone, terrified and without meaning in their lives, even

suicides could be low in the months ahead.

3

Here’s What Happened When Social Distancing Was Used During the Spanish Flu

The

economy took a hit during the 1918 influenza pandemic, but cities that

intervened earlier and more aggressively fared better.Emil Verner is an

assistant professor of finance at the MIT Sloan School of Management.

The

Covid-19 outbreak has sparked urgent questions about the impact of

pandemics on the economy. Will our effort to fight the disease by

locking down citizens and businesses do more damage than the disease

itself? Because pandemics are rare events, policymakers have little

guidance on how to manage the crisis. But looking at past pandemics—both

the public health responses and their economic impact—can provide some

insights.

The most frequently cited comparison is the 1918

Spanish flu, which similarly swept across the world and triggered

widespread shutdowns in response. In a

recent research paper,

Sergio Correia, Stephan Luck and I examined the impact of 1918 pandemic

in the United States to answer two sets of questions. First, what are

the real economic effects of a pandemic, and how long do they last?

Second, do public health interventions meant to slow the spread of the

pandemic, such as social distancing, have economic costs of their own?

Our

research compared different areas of the United States that were more

and less severely affected by the 1918 flu, as well as areas that were

more and less aggressive in their use of public health tactics to slow

it down. (The technical term for the tactics we measured is

“non-pharmaceutical interventions,” or NPIs.) The public health measures

implemented in 1918 resemble many of the policies used to reduce the

spread of Covid-19, including closures of schools, theaters and

churches, bans on public gatherings and funerals, quarantines of

suspected cases, and restrictions on business hours.

We came

away with two main insights. First, we found that areas that were more

severely affected by the 1918 flu saw a sharp and persistent decline in

real economic activity. Pennsylvania, for example, experienced a

substantial fall in manufacturing employment and banking sector assets,

compared with less affected states like Michigan. The decline in

economic activity was large—with an 18 percent decline in manufacturing

output for the typical state—and lasted for several years after 1918.

You

can see the economic disruption reflected in newspapers of the time. On

October 24, 1918, the Wall Street Journal reported: “In some parts of

the country [the flu] has caused a decrease in production of

approximately 50 percent and almost everywhere it has occasioned more or

less falling off. The loss of trade which the retail merchants

throughout the country have met with has been very large. The impairment

of efficiency has also been noticeable. There never has been in this

country, so the experts say, so complete domination by an epidemic as

has been the case with this one.”

Second, we found that cities

that implemented early and extensive public-health measures suffered no

adverse economic effects from these interventions by 1919; in other

words, the interventions did not make the economic impact of the flu

worse. On the contrary, cities that intervened earlier and more

aggressively experienced a relative increase in real economic activity

after the pandemic subsided, compared with cities that intervened less

aggressively.

Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, just across

the river from each other, illustrate the difference clearly. In 1918,

officials in Minneapolis quickly put restrictions into place and kept

them for a relatively long 116 days. Officials in St. Paul acted much

more slowly and only kept public health measures in place for 28 days.

The death rate from influenza in 1918 was 24 percent higher in St. Paul

(481 deaths compared with 388 deaths per 100,000 residents,

respectively). And Minneapolis’ economy didn’t suffer from the

restrictions. On the contrary, employment growth was twice as high in

Minneapolis in 1919 as it was in 1914, when the previous manufacturing

census was taken. These findings suggest that, at least in the medium

term, there was no tradeoff between implementing public health measures

and economic activity.

This result might be hard to grasp at a

time when millions of Americans are currently filing for unemployment

amid the coronavirus pandemic. How can it be that shutdown tactics like

school closures and restrictions on business hours could actually

benefit the economy?

The reason is that pandemic economics are

different from ordinary economics. In ordinary times, business shutdowns

and other restrictions are bad for the economy, as they limit economic

activity. But it’s important to remember that in a pandemic, the disease

itself is extremely disruptive to the economy. Households do not want

to spend money or go to work if it involves a major health risk, and

businesses do not want to invest because economic conditions are so

uncertain. The alternative to these public-health restrictions is not a

normal functioning economy, but rather a widespread, debilitating

outbreak of disease that causes major economic disruption in the short

and medium term. As a result, measures to fight the pandemic can

actually benefit the economy in the medium term, as they target the root

of what is ailing the economy—the pandemic itself.

Of course,

there are a number of important differences between the 1918 flu and the

current Covid-19 pandemic—most importantly, that the 1918 flu was

significantly more deadly for healthy, working-age adults. But our

research suggests that public health interventions such as social

distancing should not be viewed as economically costly. Doing nothing

could be far worse.

4

There’s No Tradeoff Between the Economy and Our Public Health

Both

are measures of human wellbeing. That’s what we should maximize right

now.Will Wilkinson is vice president for research at the Niskanen

Center.

In light of political pressure and expert estimates that

the Covid-19 pandemic could now rack up a six-digit American death

toll, President Donald Trump has (for now) backed down from his threat

to ease off social distancing measures, reopen the economy and “fill the

pews” on Easter. But he has

suggested nonetheless that efforts to protect the health of the American people undermine the vitality of the economy.

The

physical separation that is now necessary to contain the Covid-19

pandemic does come with a shocking price tag. Because we’re paying so

dearly to limit the risk of mass sickness and death, it can be tempting

take the next step and imagine that if we were to toughen up and bear a

bit more risk, we could maintain a much healthier economy with only a

bit more suffering and loss.

Considering the tradeoffs of one

kind of suffering against another, weighing their relative costs and

benefits, seems reasonable. But it can also lead us into error. The

tradeoff Trump has alleged between “the economy” and “public health”

conceives of them as something like knobs you can’t turn up without

turning the other down. But they are, in fact, mere abstractions,

intellectual tools for inspecting different aspects of the same thing:

the well-being of the population. Economic indicators measure well-being

(very roughly) in one way; public health indicators measure it in

another. But their common subject is how well people are doing.

Wealth

and health go hand-in-hand at both the individual and the collective

level. Because healthier populations are more productive, and wealthier

societies can afford better measures to protect the health, safety and

environment of their people, there’s generally little tradeoff between

the public health and economic performance. Tradeoffs are rife in public

policy, but the tradeoffs involved in public health initiatives around,

say, seatbelts, smoking, guns and food generally have more to do with

individual autonomy and wariness of nanny-state paternalism.

Formal

economic models abstract away from other aspects of human wellbeing

when they conceive of money as a proxy for “utility,” or the value of

consumption. More money lets you consume more (or forego less) of what

you want. A higher level of consumption, enabled by a less constrained

budget, generates a higher level of “utility” or “welfare” in economic

models simply because that’s how “utility” and “welfare” are defined in

the models. But this doesn’t necessarily tell us what we want to

know—especially when we’re struggling to contain deadly mass contagion.

“Utility,” in the economist’s formal sense, doesn’t refer to a

subjective experience of pleasure, happiness or satisfaction with life,

and “welfare” doesn’t refer to objective human health and flourishing.

None

of this is to say the means to buy the necessities and pleasures of

life is not an absolutely essential element of wellbeing. Poverty does

cause misery, sickness and death, and measures of wealth are still

incredibly valuable. But they’re valuable because we value our lives and

how well they go. Viruses don’t discriminate between rich and poor, and

the “utility” and “welfare” of economic production and consumption are

worth rather less to people struggling to breathe, and worth nothing at

all to people who are dead.

Once we acknowledge that the

epidemic and the economic slowdown aren’t really two problems, but

simply two aspects of a threat to our population’s wellbeing, the policy

response becomes clearer. Letting the epidemic rip without mitigating

measures would eventually take a catastrophic toll on the economy

anyway, in addition to the atrocity and trauma of an overwhelming level

of sickness and death. The economic cost of idling the economy to

contain the spread of the virus is more immediate than that long-term

cost, so it’s the one we are thinking about—but incurring it now better

protects the overall wellbeing of the population by minimizing the total

loss to health, life and economic capacity.

The danger of

fixating on narrow economic indicators of wellbeing, and the need to

take a more holistic perspective, has led a number of economists and

social scientists to advocate replacing measures like GDP with something

like “Gross National Happiness.” Bobby Kennedy captured the spirit of

this thinking when he famously complained that it’s confused to treat a

metric like GDP, which fails to capture “the health of our children, the

quality of their education or the joy of their play,” as the master

indicator of our society’s wellbeing. GDP does tell us roughly how much

wealth our economy produces, and how much the population has to spend,

which is something we need to know. However, as Kennedy rightly

observed, “it measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our

wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our

country, it measures everything in short, except that which makes life

worthwhile.”

Another reason that we can’t turn to economic

measures alone to understand how to respond to this crisis is that

standard economic models are upended by epidemics. These models assume

that physically proximate economic production and exchange generally

leave us, and the economy as a whole, better off. But epidemics

transform “brick and mortar” workers and customers into vectors of viral

transmission, rendering economies based on integrated networks of

physical nearness vulnerable to exponential growth in rates of deadly

infection. Dead people don’t buy anything, and rampant illness hammers

the productivity of workers and the profits of firms. Which is just to

say, in the language of economics, that contagious virulence creates a

“negative externality,” or harmful spillover effect, from physically

proximate labor and market exchange. Simply showing up for your shift at

Starbucks, or strolling in to grab a latte, means that you might be, or

might become, the living, breathing equivalent of a factory belching

toxic sludge into the drinking water.

If the risk of dangerous

infection is high, the total harm to health, life, productivity and

consumption imposed by the bustle of normal low-distance economic

activity can easily exceed its usual economic benefits. When that’s the

case, the level of spatial distancing needed to ensure that each

infection leads to less than one new infection is economically

efficient; it’s the best we can do given the constraints. Economic

growth may be impossible in the context of a galloping pandemic. The

best we can hope for is to suppress it in a way that minimizes the

severity of the economic Ice Age.

It’s crucial to grasp the main

constraint within which we are currently forced to optimize is that,

thanks to the Trump administration’s slow and hapless response, we don’t

know the real rates of infection. If we could better estimate the risk

of showing up at Starbucks, we could determine the epidemiologically

necessary and economically optimal level of social distancing. If we

knew which workers and patrons are most likely to be infected, we could

usefully surmise who can safely go on as usual and who should stay home.

For now, all we can do is focus on how to keep as many people

well as possible. In the end, measures of economic performance

alone—whether GDP or the Dow Jones—don’t always track the things we

cherish most. My wife’s mother, and my children’s one living

grandmother, is a respiratory therapist in Connecticut. We’re worried

sick about her, because we all love her, and she desperately loves my

children. Money is great, but it isn’t everything. It would be a cosmic

tragedy if we were forced to trade love against prosperity. But we

aren’t. Failing to protect the people we love won’t leave more money in

our pockets. It will leave them even emptier, and with holes in our

lives that we can never fill.

5

With a Little Ingenuity, We Can Reopen Much of the Economy Right Now

A

large swathe of jobs somewhere between “essential” and “optional” could

be reengineered so people can go back to work soon and safely.Jonathan

Caulkins is professor of operations research and public policy at

Carnegie Mellon University’s Heinz College.

The Covid-19 debate

about when and how to reopen the economy has become dangerously binary.

Yes, “life-sustaining” sectors like hospitals and electric utilities

must operate unimpeded, and optional, public-facing ones like concerts,

dine-in restaurants and theme parks likely aren’t worth the risks for

now.

But keeping Americans safe doesn’t require shuttering the

rest of our jobs. It does, however, require re-thinking how people do

them. There’s a large swathe of jobs, somewhere between essential and

optional, that could be reengineered to allow many to get back to work

soon and safely.

The logic for all-but shutting down the economy

is that doing so will stop the virus’ spread and allow mass testing to

catch up. But even with all-out shelter-in-place efforts, we will likely

still be living in the age of Covid for the rest of this year at least.

Keeping businesses’ doors completely closed will have huge costs. Given

this possibility, we need to figure out how to work sustainably in this

new reality.

The stakes are enormous. In February, the leisure

and hospitality sectors together employed 16 million Americans, and

fewer than 6 million Americans were unemployed across the entire

economy. Soon, because of limitations on social gatherings, those

figures could be reversed. That is a steep but necessary price to pay;

gatherings at bars, theaters and other public venues, are inherently

dangerous right now.

We’ve already figured out how to protect

many white-collar jobs—just work from home online. But we also can and

should reengineer some blue-collar jobs—on-premise, physical work—so it

can get done while maintaining social distancing.

Manufacturing is a prime candidate. Major automakers have

closed

their plants in North America, putting their laborers out of work. But

these companies could be allowed to reopen if they can demonstrate that

they have developed safe operating practices. True, factories involve

people working together, but so do hospitals and grocery stores. And

factories aren’t at all like bars or nightclubs: Already, the general

public isn’t allowed inside, and many are large facilities with

relatively low densities of employees because so much of the work

involves heavy machinery. China is

pioneering

ways of getting factories back online while having workers practice

social distancing. Those practices are now a crucial competitive

advantage that U.S. workers need to catch up to. To take just one small

example, painted lines could be used to define specific pathways where

people can walk on factory floors.

Like manufacturing,

construction does not directly involve the public, and is

capital-intensive. Extended hours on construction sites could let the

same work get done with fewer people on premises at any given time.

Keeping just these two sectors—manufacturing and construction—alive

could spell the difference between severe recession and depression.

Together, they employ more people in the United States (20 million) than

leisure and hospitality, and their share of economic output (23

percent) is even greater than their share of employment (12.4 percent).

Conceivably,

there are even ways that furniture, clothing and other general stores

could reopen on a limited basis, with employees but not customers

allowed on site. Knowledgeable clerks literally walking through store

displays with customers on FaceTime might have a chance to compete, at

least in some instances, with Amazon. Shutting down stores altogether

denies them that chance. If letting employees into a furniture store

seems dangerous, note that anyone can now walk into Target or Walmart to

buy a lamp or a chair right now. Those stores remain open because they

also sell groceries, even though the furniture stores with which they

compete at lamp-selling are forced to sit idle.

In addition to

opening up more of these kinds of jobs and businesses, we should also

think differently about some of the industries that are deemed “life

sustaining.” Right now, those industries can basically operate as they

see fit. That makes sense for hospitals—but not gas stations or grocery

and convenience stores.

Of course, gas stations should remain

open, but self-service involves scores of people touching the same pump

handle every day. With so many people needing work, why not require gas

to be pumped by gloved attendants with payments made online? That’s

feasible; New Jersey bans self-serve stations, and until recently so did

Oregon. Gas would be a little more expensive, but these days people are

generally willing to pay a little more for safety.

Many grocery

stores are taking steps to make their spaces safer, by sanitizing

shelves and shopping carts more frequently or capping the number of

shoppers at a given time, but they could do more. Making aisles

“one-way” would ensure that shoppers never pass each other face to face.

Produce could be pre-bagged so customers are not touching three

tomatoes before taking one, and “comparison shopping” could be

discouraged for the same reason. Before coronavirus, there was “you

break it, you buy it”; now maybe it’s “you touch it, you buy it.” At

checkout, cashiers could replace paper receipts with e-mails. (Speaking

of which, credit card companies are allowed to operate right now, but

why not push them to replace swipe cards with contact-less “tap and pay”

cards?)

It’s not that companies viewed as essential have made

no changes, but they are haphazard and undirected. A concerted and

systematic effort to reengineer public-facing essential businesses would

almost certainly cut virus transmission by more than would

reengineering and reopening shuttered sectors that don’t inherently

involve so much person-to-person interaction.

The original idea

of two-week shutdown wasn’t long enough to eradicate the virus, and a

two-month shutdown will do permanent damage to the economy. Neither

protects against Covid returning in the fall or some other pandemic

striking next year. Instead of seeing only two possible

options—reopening the economy as before or keeping it closed until

further notice—we need to be more flexible. We can start by inventing

ways to reengineer the vast middle of the U.S. economy so that it can

operate sustainably in the Covid age.

6

We Were Skeptical Social Distancing Was Worth the Economic Cost. Then We Modeled It.

The costs of slowing the economy are high. But they are worth it from an economic perspective.

Linda

Helena Thunstrom, Jason F. Shogren, David Finnoff and Stephen C.

Newbold are professors in the Department of Economics at University of

Wyoming. Madison Ashworth is a graduate student in the university's

Department of Economics. and public policy at Carnegie Mellon

University’s Heinz College.

Should we think about the economic

costs to saving lives as Covid-19 sweeps through the United States? It

seems cold-hearted to do so in the midst of a pandemic that has already

claimed more than 5,000 lives in the United States and puts millions of

others at risk. Yet we consider costs to most of the actions we take,

small and large, in our daily lives. And as the extent of lost jobs,

missed rent payments and lost healthcare from those lost jobs comes into

view, we have a responsibility to assess that damage, too.

Because

no vaccine or effective treatments are yet available for Covid-19, the

only way to slow the spread and reduce the severity of the outbreak is

to implement a strict form of social distancing. In the United States,

this has meant temporarily closing schools, universities, daycare

centers and tourist attractions, cancellations or suspensions of

national sports leagues, shelter-in-place orders and travel

restrictions. These are unprecedented measures that come at a large

economic cost.

We’re a team of economists at the University of Wyoming, and from the first days of social distancing, some of us were publicly

wondering

if the preventive measures taken to slow the spread of the virus would

incur costs that might make us regret those measures in the long run.

So,

we decided to run the numbers for a scientific article that’s currently

under peer review. And we found, using a figure known as the “value of a

statistical life” (VSL), that the value of lives saved through

distancing measures exceeds the value of lost GDP by almost $3.4

trillion. In other words, yes, social distancing is “worth it,” also

from an economist’s point of view, based on the current information

about the economic consequences and disease spread.

To come to

this conclusion, we first estimated benefits from social distancing in

terms of the value of lives saved. To do so, we used a standard

epidemiological model designed to forecast the numbers of susceptible,

infected and recovered individuals over the course of an infectious

disease outbreak. Then, we compared the predicted disease spread and

number of deaths in the United States in two scenarios: one with social

distancing measures, in which the spread is slowed and the total number

of infections is reduced, and one without social distancing measures, in

which the virus spreads unabated. For the social distancing scenario,

we assumed a contact rate between humans about 40 percent lower than

that in in the scenario without distancing. In the model, we concluded

that 1.2 million lives would be saved by social distancing measures.

Next,

we used a standard estimate for the value people assign to reducing

their personal risk of death, VSL. It’s a controversial figure among

social and behavioral scientists, given the provocative idea of

assigning values to human lives. Further, the appropriate value is

continuously debated among economists. Nevertheless, the VSL is

frequently used in official policy analyses, consistent with guidance by

the White House Office of Management and Budget. In our analysis, we

assigned a VSL of $10 million, based on the values used by federal

agencies, which gives a total value of lives saved of $12.2 trillion for

those 1.2 million people.

Next, we estimated the costs from

social distancing, in terms of the value of lost GDP. To do so, we

compared the GDP development with and without social distancing. We

forecasted GDP growth this year and the next six years.

Our

forecast with social distancing is based on macroeconomic reports by

Goldman Sachs. With social distancing, we assume GDP will drop by 6.2

percent this year (Goldman Sachs’ forecast from March 31), and that it

will take approximately three years until the economy has recovered from

the recession. Our forecast of the baseline U.S. GDP growth this year

without social distancing relies on recent macroeconomic research that

predicts the short-run economic impact of a pandemic this year, without

accounting for stringent social distancing, would cause a 2 percent

decline in GDP.

We assumed the same proportional rate of

recovery for the economy with and without social distancing, so GDP

growth would return to a new steady rate after three years in both

scenarios.

The difference in the GDP reduction of these two

scenarios—the 2 percent decline in the scenario without social

distancing, and the 6.2 percent with social distancing, with a

three-year recovery time in both scenarios—is $8.8 trillion. That’s our

estimate of the hit that the United State GDP will take over the course

of three years from social distancing lasting into the summer months

this year.

But remember, the value of lives saved was $12.2

trillion. This rapid benefit-cost analysis suggests the net

benefits—benefits from lives saved minus costs from GDP loss—amounts to

$3.4 trillion dollars. Our results suggest that social distancing passes

a cost-benefit test.

The final outcome, however, could depend

crucially on policy choices yet to be made. Much uncertainty surrounds

both the trajectory of the disease in the coming weeks and months and

that of the economy in the coming months and years. As an illustration,

based on just a 10-day-older, and more optimistic, GDP forecast by

Goldman Sachs, we found net social benefits of social distancing

amounting to more than $5 trillion, as opposed to our current best

estimate of $3.4 trillion. This illustrates an important point—we gather

more data as time goes by, and we likely will not know with confidence

the impact of social distancing on the economy or disease spread until

after the crucial policy decisions need to be made.

Further, the

public health response and the economic stimulus might determine

whether the social distancing measures taken in these crucial weeks will

be viewed as a difficult but necessary response, or instead as a gross

over- or under-reaction. But that does not take away from the importance

of doing our best to make rapid assessments that inform policy today.

We will have to live with second-guessing our decisions, but first

guesses without systematic comparisons of the benefits and costs will

likely be regretted more.