From Russia to Hungary to, now, Donald Trump’s America, a rising

authoritarianism plays on an atavistic European hatred. We live in the

Soros Age of Anti-Semitism.

Spencer Ackerman

Photo Illustration by The Daily Beast

It’s been largely forgotten, but when Russian military intelligence

created online cutouts in 2016 to manipulate the American electorate,

the Democratic Party wasn’t its only target.

The most prominent of those fake digital identities was

Guccifer 2.0,

which took credit for hacking the Democratic National Committee and

then provided the pilfered information to WikiLeaks. The other was

called DCLeaks. On Aug. 29, 2016, two months after the DNC hack became

public, DCLeaks’ now-banned Twitter account told its followers to check

out another of its projects: “

Find Soros files on soros.dcleaks.com.”

Visitors to the now-shuttered site could find purported documents from

the billionaire philanthropist’s Open Society Foundations, which promote

liberal values and democratization. They had file names like “public

health program access to medicine” and “youth exchange my city real

world.” But before those curious about the leaks got there, the Russians

wanted to put George Soros in a particular context.

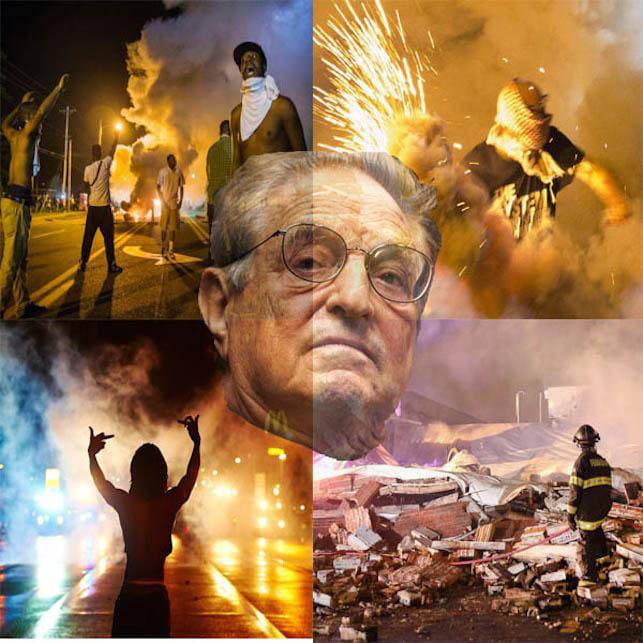

The

homepage displayed a photo illustration of a smug-looking Soros in the midst of four scenes of street chaos whose apparent perpetrators

were conspicuously nonwhite.

They were taken from the Ferguson, Missouri, protests in 2014, the

birthplace—to the consternation of many white Americans whom the Kremlin

sought to cultivate—of the contemporary civil rights movement. In both

the image and the accompanying text, the Russians portrayed Soros as the

puppet master.

“Soros is named as the architect and sponsor of almost every revolution

and coup around the world for the last 25 years. Thanks to him and his

puppets USA is thought to be a vampire, not a lighthouse of freedom and

democracy,” the website proclaimed. The “oligarch” who sired the U.S.

vampire, and whose “slaves spill blood of millions and millions people

just to make him even more rich” [sic], had a particular background the

Russians highlighted in the very first sentence: Soros is “of

Hungarian-Jewish ancestry and holds dual citizenship.”

More than two years later, the president of the United States gave a

similar portrayal of Soros, though Trump left Soros’s background unsaid.

Soros, Trump said on Friday, Oct. 5, had paid for “

professionally made identical signs”

in the hands of women objecting to Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court

justiceship. On Tuesday, he followed up by implying that Soros had

stiffed these hired “

screamers.” In Trump-like fashion, his accusations were a form of mirror-imaging, as Trump himself had

paid for people to support his presidential announcement and

denied them payment for months, and he appears to have misunderstood a Fox News guest who

spoke sarcasticallyabout Soros paying the protesters.

But it was not Trump’s first time making sinister allegations about

Soros. He did so in the final advertisement from his campaign, run at

the time by the

blood-and-soil nationalist Steve Bannon.

Its message was reminiscent of the darker periods of European history:

the virtuous future of the forgotten, salt-of-the-earth people has been

stolen by a predatory elite. As a shot of the Capitol Dome faded into a

Wall Street sign, Trump narrated a message to “those who control the

levers of power in Washington” right as the camera showed an image of

Soros, giving way to a shot of then-Federal Reserve chairwoman Janet

Yellen, who is also Jewish, as Trump continued speaking about “global

special interests.” This followed months of the so-called alt-right

transforming “globalism” into an anti-Semitic euphemism, and preceded

Trump stocking his cabinet with ultra-rich financiers, Jew and gentile

alike.

In the 1980s and 1990s, George Soros was hailed as an anti-communist and

post-communist hero. His philanthropy helped smooth democratic

transitions from the Soviet orbit in central and Eastern Europe.

Alongside that track record was a different one: Soros was a ruthless

currency speculator who benefited from, among other things,

the 1992 British financial disaster

and who once blithely dismissed second thoughts over the world-moving

power of his investments, saying, “I am engaged in an amoral activity

that is not meant to have anything to do with guilt.” In a 60 Minutes

interview from 1998—one that Glenn Beck would famously butcher to

paint Soros, who as a boy lived through Nazi occupation, as a Nazi collaborator—Jim Grant of

Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, remarked that Soros was “Donald Trump without the humility.”

The current portraiture of Soros, now ascendant if not dominant online,

isn’t interested in that sort of complexity. For the far right, from

Russia to central Europe and increasingly, America, Soros is the latest

Jewish manipulator whose extreme wealth finances puppet groups and

publications to drain the prosperity of the

Herrenvolk.

This cannot be dismissed as the preoccupation of ignorable fools on the

internet, nor as the equivalent of liberal criticism of the Koch

Brothers. Instead, the attack on Soros follows classic anti-Semitic

templates, grimly recurrent throughout western history, and some of the

most powerful geopolitical figures in the world are pushing it. It’s

fueled by Soros’s political activism against a revanchist right

eager to view the world in zero-sum racial terms that is on the march across Europe, America and beyond.

“The attack on Soros follows classic anti-Semitic templates, grimly

recurrent throughout western history, and some of the most powerful

geopolitical figures in the world are pushing it.”

Other Jewish bogeymen may haunt the fever dreams of the vicious, but the

scale and intensity of the attacks on Soros are unrivalled. They reveal

what the global nationalist right believes is at stake in this present

moment. We may one day look back on this era as the Soros Age of

anti-Semitism.

“It’s important to distinguish between intent and effect. Of course a

person who shares a conspiracy theory about George Soros may not intend

to promulgate anti-Semitism, and of course not every Soros conspiracy

theory is anti-Semitic. But the image of the rich, powerful Jew who

manipulates social and political movements around the world for his own

agenda is an ancient anti-Semitic trope,” said Aryeh Tuchman, the

associate director of the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism.

“Because Soros’s Jewish identity is so well known, we are concerned that

conspiracy theories about George Soros may have the effect of

reinforcing this trope and spreading it throughout the broader

population,” Tuchman added. “This is especially true when other

anti-Semitic tropes are woven in, such as claims that Soros controls the

media or the banks, or when he is described using terms that harken

back to medieval claims that Jews are evil, demonic, or agents of the

Antichrist.”

There will always be this sort of

tentacular George Soros figure. There have been many before. One was said to have profited off the bloodshed at Waterloo.

Thirty years after the pivotal battle capping the end of the Napoleonic

Wars, a pamphlet circulated across Europe claiming that Nathan

Rothschild, a London banker and scion of the Jewish mega-financier

family, sped from the battlefield to parlay his insider knowledge of the

French defeat into a windfall on the London stock exchange. “This

family,”

charged an author writing under the nom de plume “Satan,” “is our evil genius.”

It was the fake news of its era. Nathan Rothschild was never at Waterloo.

He died five years before the pamphlet’s publication

in 1841, leaving him unable to rebut it. But the lie, after a series of

adjustments to explain away its baseline factual mistakes, would reach

escape velocity. One subsequent version, according to Brian Cathcart of

Kingston University London, claimed Rothschild “deliberately provoked a

collapse in stock market confidence by encouraging rumors that

Wellington had been defeated.”

Nathan Mayer Rothschild (1777-1836), from a painting. (Photo by Culture Club/Getty Images)

Lebrecht

The form of conspiracy theories follows their function. Here was a

Jewish family whose fortune was said to derive from exploiting European

carnage. As Jews, they were considered a foreign presence on the

continent, one that had taken advantage of their adopted countries’

naive openness to establish a shadowy power that could determine the

fate of nations. Accordingly, European publics would not have to look to

their distant autocratic governments for their political

disenfranchisement, nor would they have to look to a confusing system of

capitalist finance to explain obscene discrepancies in wealth. In place

of a systemic critique was a Jewish face. More recently, you can find

Rothschild references in the

QAnon conspiracy theory, alongside, of course, Soros.

A recurrent theme of 19th-century anti-Semitism is that it finds

substantial currency at moments when old regimes appear exhausted and

fear about revolutionary dislocation intensifies. A tutor to Russia’s

final two tsars demonstrated the utility of using Jews as an omnibus

explanation for the anxieties of his age. Jews in Russia endured

repression of their civil and economic rights—but they only appeared

powerless.

“Yids,” wrote Konstantin Pobyedonostsev in August 1879, have “invaded

everything, but the spirit of the times works in their favor. They are

at the root of the Social Democratic movement and tsaricide. They

control the press and the stock market. They reduce the masses to

financial slavery. They formulate the principles of contemporary

science, which tends to disassociate itself from Christianity. And in

spite of that, every time their name is mentioned, a chorus of voices is

raised in favor of the Jews, supposedly in the name of civilization and

tolerance, that is to say, indifference to faith. And nobody dares say

that here the Jews control everything.” Like many before and since,

Pobyedonostsev did not pause to reconcile his claimed Jewish interest in

exploitative capitalism with his claimed Jewish interest in the

socialism designed to destroy it, but a man like George Soros offers

Pobyedonostsev’s descendants a way to square the circle.

After Rothschild, there was Max Warburg. Warburg, another Jewish banker,

was a member of the Hamburg parliament and said to have an open line to

Kaiser Wilhelm II. Once Pobyednostsev’s fears came true in 1917, a

forgery about Warburg appeared in Petrograd claiming that he and a

“Rhenish-Westphalian syndicate” were financing the Bolsheviks, through

the Jewish Trotsky.

A Russian journalist, Eugene Semyonov, provided the forgery to an

American diplomat, Edgar Sisson. It had currency for the Creel

Committee, an official U.S. government propaganda organ promoting

participation in World War I, since it portrayed the Russian Revolution

as a German plot financed by Jews. In September 1918, the committee

published it under the title The German-Bolshevik Conspiracy.

Leon Poliakov writes in the fourth volume of his History of

Anti-Semitism that it was the first time that an anti-Semitic forgery

was published by a government that was neither tsarist nor otherwise

committed to anti-Semitism as a matter of policy. (Warburg himself, 20

years later, would

immigrate to New York to flee the Nazis.)

According to Poliakov, the years between the world wars were a boom time

for anti-Semitic forgeries in the United States. There was the fake

George Washington missive, warning that the Jews, not the British Army,

were the principal danger. And there was a fake Ben Franklin prophesy,

forecasting Jewish world domination by 1950 or so. Detectives hired by

the anti-Semitic industrialist Henry Ford traveled to Mongolia, of all

places, in pursuit of an authentic Hebrew copy of the invented Protocols

of the Elders of Zion. Another went “looking for the secret channel

through which [Supreme Court Justice and Jew] Louis Brandeis gave his

orders to the White House.”

Foreshadowing the present day, the upswing of American anti-Semitism

came at the intersection of an immigration panic, an ascendant nativist

movement, and fears about foreign-borne internal subversion. As the

Bolshevik Revolution spread, so did a cottage industry of paranoiacs

connecting it to mainstream American Jewry, just as a

later generation of Islamophobes would do to American Islam after 9/11.

In 1919, a Methodist minister recently driven from Russia, the Rev.

George A. Simons, testified to a Senate subcommittee about the

Jewishness of Bolshevism.

Simons, speaking through barely concealed euphemism, told the Senate

that he had encountered “hundreds of agitators” in the former St.

Petersburg who had come from “the East Side of New York,” meaning the

Jewish slum. The typical sentiment of Russians to describe the

post-revolutionary arrangement, Simons related, was that “it is not a

Russian government, it is a Hebrew government.” But, Simons assured the

Senate, he was no bigot: “I am not in sympathy with anti-Semitism. I

never was and never will be. I hate pogroms of any type. But I am firmly

convinced that this business is Jewish.”

Vladimir Putin and the global nationalist right have particular

motivations to vilify Soros, though deploying anti-Semitism to do it is

entirely their choice.

Soros was deeply involved in post-Soviet economic efforts in Russia in

the 1990s, corresponding with the nadir of Russian power that Vladimir

Putin considers a national humiliation demanding redress. And though

he’s denied doing any such thing,

Russians have long speculated that Soros

profited off a Russian economic downturn in 1998,

a year during which he boasted of being Russia’s largest single

investor. (His Quantum Fund claims to have lost $2 billion from the

episode.) Prophetically, Soros

warned Charlie Rose

in 1995 of revanchist eastern-European authoritarianism born of an

alliance between nationalist politicians and business interests: “Russia

is very much up for grabs. It’s very much a struggle which way it’s

going to go.”

Soros’s solution to all of this is liberalism. He took his inspiration

from the anti-totalitarian philosopher Karl Popper, best known for

The Open Society and Its Enemies, and used Popper’s work to develop a critique of the rapacious capitalism Soros himself practiced

as a threat to that open society—conveniently,

after he had made his billions. Soros’s Open Society Foundations, which

operate in over 140 countries, provide assistance and financing to

civil-society institutions that promote transparency, the rule of law,

higher education, refugee aid, the rights of marginalized peoples, and

democratic accountability.

Accordingly, recipients of Soros’s philanthropy include groups such as

NARAL, Planned Parenthood and the ACLU that in their various ways oppose

the agendas of the American right. In 2003, Soros pledged

what would for anyone other than him count as a fortune in a failed attempt to prevent George W. Bush’s re-election, fanning the flames of his

enemies’ ire. Then, in October 2017, the elderly Soros transferred

a gargantuan $18 billion to the foundation, making it the U.S.’ second largest philanthropic organization.

But it’s one thing to be a wealthy donor, even an unfathomably wealthy

one: American politics, to its cross-ideological abasement, relies upon

them, and scrutiny of them is vital for the very open societies Soros

promotes. It’s quite another for such an unfathomably wealthy donor to

stand as a singular, nefarious explanation for all manner of global

political phenomena. A recent ADL study about

anti-Semitism on Twitter took

particular note

of the frequency and virulence of invocations of Soros for

“undermin[ing] western civilization, or following a long-standing

pattern of Jewish behavior.” The ADL even found far-right warnings that

Soros had engineered the lethal white-supremacist march on

Charlottesville as a false-flag operation.

After the teenage survivors of the Parkland high school massacre began

their demonstrations for gun control, some let the mask slip. One

now-suspended “alt-right” account tweeted that it was “@georgesoros at

work.”

Softer

versions of that sentiment are ubiquitous online. One more humorous

version came after someone posted a picture of a bald Britney Spears

attacking a car during her 2007 meltdown to joke that it was Parkland’s

Emma Gonzalez – prompting an apparently elderly woman to tweet that “

these children of Satan… are funded by Soros.”

At an “alt-right” gathering in New York convened by Pizzagate

conspiracy theorist Mike Cernovich, drunken panelists referred to Soros

as the “

head of the snake.”

Larger players in the “alt-right” firmament, echoing their 19th- and

20th-century antecedents, find the malevolent handiwork of Soros

everywhere. WikiLeaks, on Twitter, sought to discredit 2016-era

reporting in the Panama Papers concerning Vladimir Putin by

portraying it as Soros-funded.

Bannon’s former home for distorted news, Breitbart, ran a cottage

industry connecting far-right targets to Soros, no matter how innocuous

the connection. In a typical piece, H.R. McMaster’s

consultancy

at the International Institute for Strategic Studies – a minor thing,

considering it overlapped with McMaster’s Army career – became “

Soros-funded” through a IISS affiliation with the nuclear-nonproliferation Ploughshares Fund.

Google and

Facebook

were hit with similar Breitbart smears-by-association through their

sins of using credible organizations like the Poynter Institution, which

take Open Society money, to reduce the onslaught of fake news. InfoWars

similarly

highlights Soros money taken by its critics to paint itself as unfairly persecuted.

In keeping with the broader trajectory of the extreme right, the

paranoid conception of Soros has moved closer to the corridors of power.

In December, the GOP nominee for Senate in Alabama, Roy Moore,

castigated Soros in terms redolent with anti-Semitism. Soros’s agenda

was “sexual” in nature, said

a man accused of child predation, and it’s “not our American culture.” Soros,

Moore told a radio host,

“comes from another world that I don’t identify with. … No matter how

much money he’s got, he’s still going to the same place that people who

don’t recognize God and morality and accept his salvation are going.”

“Soros’s agenda was ‘sexual’ in nature, said Roy Moore, a man accused of

child predation. Soros ‘comes from another world that I don’t identify

with. … No matter how much money he’s got, he’s still going to the same

place that people who don’t recognize God and morality and accept his

salvation are going.’”

That same month, Erik Prince, brother of Trump’s education secretary and

mercenary CEO, encouraged a GQ reporter to investigate the Clintons’

sartorial choices of purple shirts and ties. “Purple Revolution lore,”

the wealthy Prince told GQ. “

I think it’s a Soros thing.”

(There is no such thing as the Purple Revolution.) A Prince associate

and former CIA official, the Intercept reported last year, told would-be

donors that McMaster used a burner phone to route the fruits of

deep-state surveillance on Bannon and the Trump family to “

a facility in Cyprus owned by George Soros.”

More recently, after the Kavanaugh confirmation fight, Senator Chuck

Grassley stopped just short of validating the accusation that Soros had

paid for those protesting Kavanaugh. “I believe it fits in his attack

mode that he has, and how he uses his billions and billions of

resources,”

said the chairman of the Senate judiciary committee. Even Rudy Giuliani on Saturday

retweeted someone who called Soros the “anti-Christ.” The “evil genius” that “Satan” concocted in 1841 had found its 2018 incarnation.

Nowhere has the attack on Soros been more geopolitically potent, or as clarifying, as in his native Hungary.

The Hungarian strongman prime minister Viktor Orban, for months ahead of

his April reelection, united anti-Semitism and Islamophobia to portray

Soros as the

string-puller behind a transformational Islamic invasion of Syrian migrants. Whereas some Soros opponents mumble through their anti-Semitism, Orban roars it. Soros is out to deal “

a final blow to Christian culture,”

Orban charged in November. “It’s Soros’s plan for America, too. PM

Orban’s view is deeply well informed & reasoned,” the racist Iowa

Republican Congressman Steve King said in December while

quote-tweeting an account that used the Soros photo illustration from the DCLeaks page.

In a March pre-election speech, Orban put Soros and immigration in

existential terms for Hungary. He pledged to expel Soros as the

Hungarians did previous remote tyrannies from

the Ottomans to the Hapsburgs to the Soviets. And he applied anti-Semitic tropes not seen from a European leader since Hitler.

“We are fighting an enemy that is different from us,” Orban said, per

a New York Times translation.

“Not open, but hiding; not straightforward but crafty; not honest but

base; not national but international; does not believe in working but

speculates with money; does not have its own homeland but feels it owns

the whole world.” Even a previously sympathetic writer, National

Review’s Michael Brendan Dougherty, said the speech read like “

a checklist drawn from the Protocols of the Elders of Zion.”

Perhaps it’s worth noting that Orban himself received a

Soros-funded scholarship to Oxford.

But it was not the only irony in this ugly episode. To its discredit,

the Israeli government of Benjamin Netanyahu wilfully averted its eyes

from Orban’s anti-Semitism. Billboards in Hungary last year promoted

Orban’s anti-immigrant agenda by using a photo of a smiling Soros to

warn Hungarians against letting him get “the last laugh.” Yossi Amrani,

the Israeli ambassador, posted on Facebook that the campaign sowed “sad

memories”—an apparent allusion to

Hungary’s complicity in genocidal anti-Semitism—and “hatred and fear.”

Yet the Israeli foreign ministry undercut its own diplomat. It

insisted

it had no intent to “delegitimize criticism of George Soros, who

continuously undermines Israel's democratically elected governments by

funding organizations that defame the Jewish state and seek to deny it

the right to defend itself.” That followed on Israel opting to accept

official assurances against anti-Semitism after Orban called Miklós

Horthy—Hitler’s Hungarian ally whose expulsions of Hungarian Jewry led

to the slaughter of half a million people in the Holocaust—an “

exceptional statesman.”

An Israeli journalist, Mairav Zonszein, contextualized the toleration of

anti-Semitism within Netanyahu’s broader alignment with right-wing

nationalist governments “

if it will bolster the Greater Israel movement.”

This appears to be an allusion to Soros’s funding of Israeli groups

such as B’tselem and Breaking The Silence, which challenge the brutal

Israeli treatment of Palestinians, an internal criticism that Netanyahu

and his allies cannot abide. Netanyahu, who

postures as the protector of diaspora Jewry when it suits him, had tacitly collaborated with an anti-Semite to turn a Hungarian-born Jew into a metaphorically stateless person.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban and Israeli Prime Minister

Benjamin Netanyahu shake hands after making joint statements at the

prime minister's office in Jerusalem, Israel.

This spring, Orban’s government

criminalized the assistance of asylum seekers and undocumented immigrants through what it called the “Stop Soros” laws. Ahead of its passage, the Open Society Foundations announced that it would

cease operations in Budapest and transfer its local staff to Germany. In July, Netanyahu hosted Orban in Jerusalem and declared him a “

true friend of Israel.”

Calculations like Netanyahu’s underscore the ascendancy and the purpose

of the global far right. From Russia to America and beyond, the open

society is on its back foot against an assault not seen since the 1930s.

The assaulters are far from finished. Whereas the previous generation

of European nationalists wanted to marginalize the European Union, the

current one seeks to take it over. Orban and his Italian ally, Interior

Minister Matteo Salvini, are

crusading on an anti-immigration platform

ahead of spring’s European Parliamentary elections. They’re joined, on

the outside, by Steve Bannon, who dreams of a pan-European nationalist

bloc and styles himself, as

he told The Daily Beast’s Nico Hines,

a counterweight to the version of George Soros so thoroughly cultivated

for the reactionary European, Russian and American imagination.

Soros would not talk for this article. But the Open Society Foundations’

communications director, Laura Silber, called the attacks on him “a

tribute,” as his philanthropy “strikes at the interests of autocrats,

oligarchs and corrupt politicians” and supports human dignity.

“The voices that are loudest in speaking out against George Soros are

those that are authoritarian, seeking to galvanize their bases and

consolidate power, ignoring or silencing the most vulnerable,” Silber

told The Daily Beast. “They’re doing it by circulating recurrent tropes.

The billboards that the Hungarian government put up were eerily similar

to World War II propaganda, and it’s telling that they were defaced

with swastikas and hateful epithets.”

“The voices that are loudest in speaking out against George Soros are

those that are authoritarian, seeking to galvanize their bases and

consolidate power, ignoring or silencing the most vulnerable.”

— Laura Silber

The U.S. has been better to and for Jews than any other diaspora nation

in history. It’s for that reason that many American Jews, particularly

those whose white skin affords them access to the highest levels of the

American Dream, often diminish the dangers posed by a mass movement

comfortable, wittingly or not, with creating a Jewish scapegoat for its

political frustrations. There is also a powerful Jewish collective

instinct to avoid calling attention to empowered anti-Semitism for fear

of provoking it to violence.

Nearly a century ago, as anti-Semitic propaganda backed by powerful

white Americans like Henry Ford proliferated, an American Jewish lawyer

and civil-rights leader urged his fellow Jews to confront it. “Events

have shown that the policy of silence was a mistake. Not only do Ford’s

articles appear every week with undiminished virulence, but worse, the

Protocols is distributed in every club, placed in every newspaper,”

wrote Louis Marshall in 1921. “It has been received by every member of

Congress and put in the hands of thousands of personalities. It is the

topic of conversation in every living room and in every social sphere.”

Eighteen years later,

20,000 Nazi supporters filled Madison Square Gardento preach their vision of an American Reich. It would not be long, across the Atlantic, before much worse unfolded.

“I’m concerned that the prevalence of conspiracy theories about Soros

which paint him as a larger than life, powerful figure has the effect of

shrinking that public space where anti-Semitism is not acceptable,”

said the ADL’s Tuchman. “If you have fully embraced the notion that

there is a powerful Jewish figure manipulating social and political

movements around the world to promote his agenda, you’re inching toward

the edges of that space where anti-Semitism is acceptable. Soros is a

liminal figure in that way.”

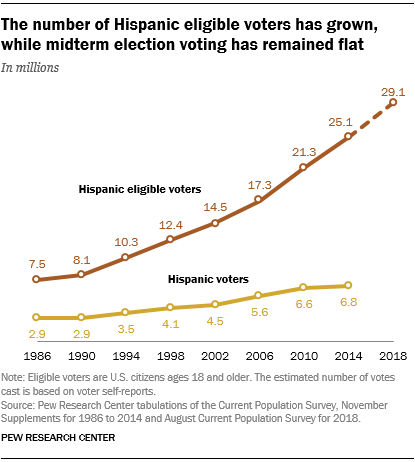

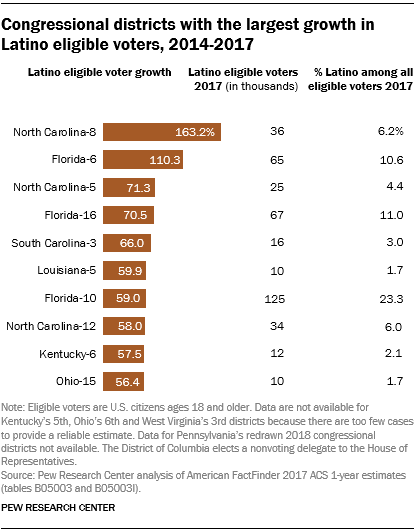

More

than 29 million Latinos are eligible to vote nationwide in 2018, making

up 12.8% of all eligible voters – both new highs, according to a new

Pew Research Center analysis of Census Bureau data.

More

than 29 million Latinos are eligible to vote nationwide in 2018, making

up 12.8% of all eligible voters – both new highs, according to a new

Pew Research Center analysis of Census Bureau data.

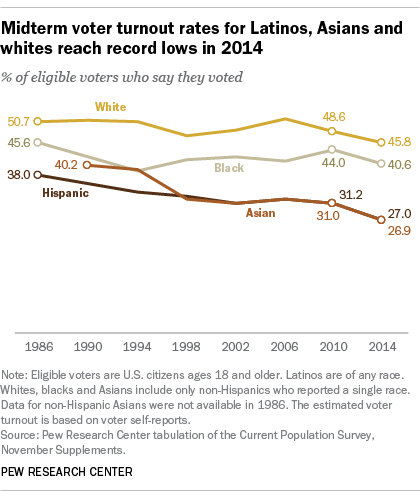

The

Latino voter turnout rate in midterm elections has declined since 2006.

In 2014, the turnout rate among Latino eligible voters dropped to a

record low of 27.0%. (White and Asian eligible voters also had

record-low turnout rates.) Despite this, a record 6.8 million Latinos

voted.

The

Latino voter turnout rate in midterm elections has declined since 2006.

In 2014, the turnout rate among Latino eligible voters dropped to a

record low of 27.0%. (White and Asian eligible voters also had

record-low turnout rates.) Despite this, a record 6.8 million Latinos

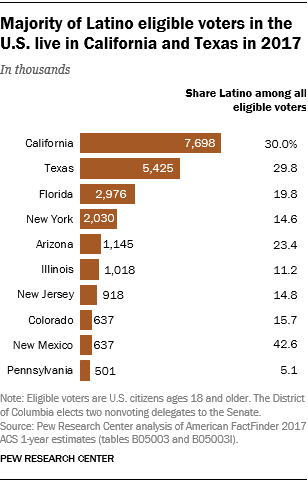

voted.  About

seven-in-ten (71%) Hispanic eligible voters live in just six states in

2017 – California (7.7 million), Texas (5.4 million), Florida (3.0

million), New York (2.0 million), Arizona (1.1 million) and Illinois

(1.0 million). Hispanics make up the highest share of all eligible

voters in New Mexico (42.6%), followed by California (30.0%), Texas

(29.8%), Arizona (23.4%) and Florida (19.8%).

About

seven-in-ten (71%) Hispanic eligible voters live in just six states in

2017 – California (7.7 million), Texas (5.4 million), Florida (3.0

million), New York (2.0 million), Arizona (1.1 million) and Illinois

(1.0 million). Hispanics make up the highest share of all eligible

voters in New Mexico (42.6%), followed by California (30.0%), Texas

(29.8%), Arizona (23.4%) and Florida (19.8%).  There

are 176 congressional districts with at least 50,000 Latino eligible

voters in 2017, and they contain nearly 80% of all Latino eligible

voters. In one California district and three in Texas, Hispanics make up

at least three-quarters of all eligible voters: California’s 40th

District (81.0%) and Texas’ 34th (79.3%), 16th (76.5%) and 15th (75.1%).

All four districts have Democratic incumbents. Texas’ 20th District,

which covers part of San Antonio, has 357,000 Hispanic eligible voters,

the most of any congressional district in the nation.

There

are 176 congressional districts with at least 50,000 Latino eligible

voters in 2017, and they contain nearly 80% of all Latino eligible

voters. In one California district and three in Texas, Hispanics make up

at least three-quarters of all eligible voters: California’s 40th

District (81.0%) and Texas’ 34th (79.3%), 16th (76.5%) and 15th (75.1%).

All four districts have Democratic incumbents. Texas’ 20th District,

which covers part of San Antonio, has 357,000 Hispanic eligible voters,

the most of any congressional district in the nation.