There

is a host of ways Americans’ opinions about climate issues divide. The

divisions start with views about the causes of global climate change.

Nearly half of U.S. adults say climate change is due to human activity

and a similar share says either that the Earth’s warming stems from

natural causes or that there is no evidence of warming. The disputes

extend to differing views about the likely impact of climate change and

the possible remedies, both at the policy level and the level of

personal behavior.

There

is a host of ways Americans’ opinions about climate issues divide. The

divisions start with views about the causes of global climate change.

Nearly half of U.S. adults say climate change is due to human activity

and a similar share says either that the Earth’s warming stems from

natural causes or that there is no evidence of warming. The disputes

extend to differing views about the likely impact of climate change and

the possible remedies, both at the policy level and the level of

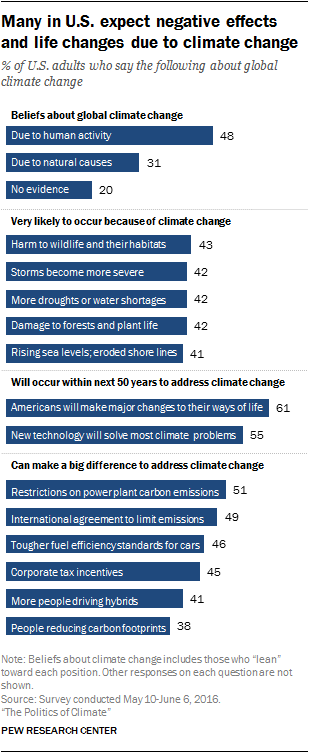

personal behavior. Roughly four-in-ten Americans expect harmful effects from climate change on wildlife, shorelines and weather patterns. At the same time, many are optimistic that both policy and individual efforts to address climate change can have an impact. A narrow majority of Americans anticipate new technological solutions to problems connected with climate change, and some 61% believe people will make major changes to their way of life within the next half century.

On all of these matters there are wide differences along political lines with conservative Republicans much less inclined to anticipate negative effects from climate change or to judge proposed solutions as making much difference in mitigating any effects. Half or more liberal Democrats, by contrast, see negative effects from climate change as very likely and believe an array of policy solutions can make a big difference.

Americans

who are more deeply concerned about climate issues, regardless of their

partisan orientation, are particularly likely to see negative effects

ahead from climate change, and strong majorities among this group think

policy solutions can be effective at addressing climate change.

Americans

who are more deeply concerned about climate issues, regardless of their

partisan orientation, are particularly likely to see negative effects

ahead from climate change, and strong majorities among this group think

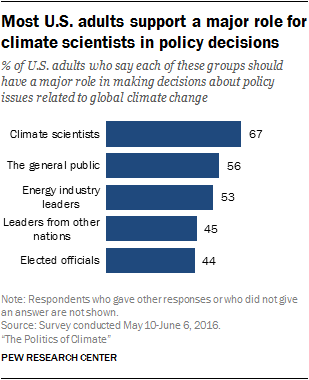

policy solutions can be effective at addressing climate change. Roughly two-thirds of Americans say climate scientists should have a major role in policy decisions about climate matters, more than say that the public, energy industry leaders, or national and international political leaders should be so involved.

But, overall, majorities of Americans appear skeptical of climate scientists. No more than a third of the public gives climate scientists high marks for their understanding of climate change; even fewer say climate scientists understand the best ways to address climate change. And, while Americans trust information from climate scientists more than they trust that from other groups, fewer than half of Americans have “a lot” of trust in information from climate scientists (39%).

A

minority of Americans perceive that the best available scientific

evidence is driving climate research findings most of the time. And a

roughly equal share says other, more negative, factors influence climate

research.

A

minority of Americans perceive that the best available scientific

evidence is driving climate research findings most of the time. And a

roughly equal share says other, more negative, factors influence climate

research. People’s trust and confidence in climate scientists varies widely depending on their political orientation. Liberal Democrats are much more trusting of climate scientists’ understanding of the issue and disclosure of full and accurate information about it. Republicans, particularly conservatives, are highly critical of climate scientists and more likely to ascribe negative rather than positive motives to the influences shaping scientists’ research.

This chapter provides an overview of Americans’ attitudes about climate change and climate scientists. It then details the divides in these views among political groups and among those who are more or less concerned about climate issues. Americans who care more about the issue of climate change, regardless of political orientation, are more trusting of climate scientists, more likely to expect negative effects to occur because of climate change, and more likely to believe that both individual efforts and policy actions can be effective in addressing climate change.

Beliefs about global climate change remain fairly stable

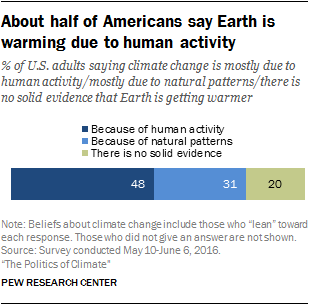

Roughly

half of adults (48%) say climate change is mostly due to human

activity; roughly three-in-ten say it is due to natural causes (31%) and

another fifth say there is no solid evidence of warming (20%).

Roughly

half of adults (48%) say climate change is mostly due to human

activity; roughly three-in-ten say it is due to natural causes (31%) and

another fifth say there is no solid evidence of warming (20%).  The share saying human activity is the primary cause of climate change is about the same as Pew Research Center surveys

in 2014 (50%) and 2009 (49%). Center surveys from 2006 to 2015 using

somewhat different question wording found a similar share expressing

this view (45% in the most recent, 2015 survey).

The share saying human activity is the primary cause of climate change is about the same as Pew Research Center surveys

in 2014 (50%) and 2009 (49%). Center surveys from 2006 to 2015 using

somewhat different question wording found a similar share expressing

this view (45% in the most recent, 2015 survey). There is a broad public expectation that climate change will have negative effects on animal and plant life, shorelines and weather patterns

Large

majorities of Americans think global warming will lead to an array of

negative effects for the Earth’s ecosystems. At least three-quarters of

Americans say that harm to animal habitats and plant life is very or

fairly likely to occur. A similar share expects storms to become more

severe and damage to shorelines or more frequent droughts to occur.1

Large

majorities of Americans think global warming will lead to an array of

negative effects for the Earth’s ecosystems. At least three-quarters of

Americans say that harm to animal habitats and plant life is very or

fairly likely to occur. A similar share expects storms to become more

severe and damage to shorelines or more frequent droughts to occur.1  Americans

who believe global climate change is the result of human activity are

far more likely than other Americans (those who believe climate change

results from natural patterns or that there is no evidence of global

warming) to say each of these effects is very likely.

Americans

who believe global climate change is the result of human activity are

far more likely than other Americans (those who believe climate change

results from natural patterns or that there is no evidence of global

warming) to say each of these effects is very likely. A 61% majority of the public expects Americans will make major changes to their ways of life in order to address problems from climate change within the next half century, while 38% do not expect this to occur. The public, as a whole, sides to optimism (55% to 44%) that new technological solutions will arise within the next 50 years that can solve most of the problems from climate change.

Roughly half of U.S. adults say restrictions on power plant emissions, international agreements can bring change; a sizeable minority sees individual efforts as effective too

There are a number of different proposals to address climate change. The Pew Research Center survey explored people’s views about whether each of several policy and individual actions can be effective at addressing climate change.

Americans

are largely optimistic that restrictions on power plant emissions (51%)

and international agreements to limit carbon emissions (49%) can make a

big difference to address climate change. The Obama administration announced stricter limits on power plant emissions in 2015. This year, more than 175 countries, including the U.S., have signed the Paris Agreement, which aims to reduce carbon emissions around the world.

Americans

are largely optimistic that restrictions on power plant emissions (51%)

and international agreements to limit carbon emissions (49%) can make a

big difference to address climate change. The Obama administration announced stricter limits on power plant emissions in 2015. This year, more than 175 countries, including the U.S., have signed the Paris Agreement, which aims to reduce carbon emissions around the world. Public assessments of other policy proposals are similar. Some 46% say tougher fuel efficiency standards for cars and trucks can make a big difference in addressing climate change; 45% say corporate tax incentives that encourage businesses to reduce carbon emissions caused by their actions can too.

About four-in-ten Americans (41%) say having more hybrid and electric vehicles on the road can have a big effect; 38% think people’s efforts to reduce their own “carbon footprints” as they go about daily living can make a big difference, while another 44% say this can make a small difference.

Who do Americans want most at the policy table? Climate scientists, followed by the public. Fewer say elected officials, international political leaders should have a major role

A

majority of Americans say that climate scientists should have a role in

policy decisions about climate issues. Two-thirds (67%) of U.S. adults

say climate scientists should have a major role and 23% say they should

have a minor role. Just 9% say climate scientists should have no role in

policy issues regarding global climate change.

A

majority of Americans say that climate scientists should have a role in

policy decisions about climate issues. Two-thirds (67%) of U.S. adults

say climate scientists should have a major role and 23% say they should

have a minor role. Just 9% say climate scientists should have no role in

policy issues regarding global climate change. Following scientific experts on the list, 56% of adults say the general public should have a major role in policy decisions about climate issues, followed by 53% that name energy industry leaders.

By comparison, fewer Americans believe elected officials should have a major role in climate policy decisions. In all, 44% of U.S. adults say elected officials should have a major role, another four-in-ten (40%) say elected leaders should have a minor role in climate policy-making.

Public views about the role of elected officials in policy decisions on climate issues may tie with deep public cynicism about the federal government, generally. Or, as shown later in this chapter, those beliefs could tie to distrust that elected officials provide full and accurate information about the causes of climate change.

People’s normative views about the place of international leaders in these decisions are similar to that for U.S. leaders.

Minority of public sees consensus among climate scientists over causes of global warming

Scientists first noted the possibility that the burning of greenhouse gases, such as fossil fuels, could increase temperatures back in the 1800s. A report from National Academy of Sciences in 1977 warned that the burning of fossil fuels could result in average temperatures increases of 6 degrees Celsius by the year 2150.2

The

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which reflects

scientific opinion on the topic, stated in the forward to its 2013

report, “the science now shows with 95 percent certainty that human

activity is the dominant cause of observed warming since the mid-20th

century.”3 And, several analyses of scholarly publications suggest widespread consensus among climate scientists on this point.4

The

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which reflects

scientific opinion on the topic, stated in the forward to its 2013

report, “the science now shows with 95 percent certainty that human

activity is the dominant cause of observed warming since the mid-20th

century.”3 And, several analyses of scholarly publications suggest widespread consensus among climate scientists on this point.4 Similarly, a Pew Research Center survey of members of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) found 93% of members with a Ph.D. in Earth sciences (and 87% of all members) say the Earth is warming mostly because of human behavior.5

But, in the public eye, there is considerably less consensus. Just 27% of Americans say that “almost all” climate scientists hold human behavior responsible for climate change. Another 35% say more than half of climate scientists agree about this, while an equal share says that about fewer than half (20%) or almost no (15%) scientific experts believe that human behavior is the main contributing factor in climate change.

Consistent with previous Pew Research Center studies, people’s perceptions of consensus among climate scientists are closely related to their beliefs about global climate change. Among those who say climate change is due to human activity, many more say scientists are in agreement on the main cause of climate change.

U.S. public is largely skeptical of climate scientists’ understanding of climate change

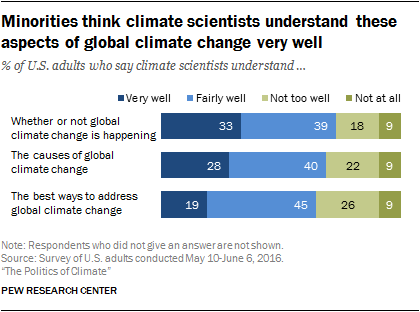

Americans

appear to harbor significant reservations about climate scientists’

expertise and understanding of what is happening to the Earth’s climate.

One-in-three adults (33%) say climate scientists understand “very well”

whether climate change is occurring, another 39% say scientists

understand this “fairly well” and some 27% say scientists don’t

understand this “too well” or don’t understand it at all.

Americans

appear to harbor significant reservations about climate scientists’

expertise and understanding of what is happening to the Earth’s climate.

One-in-three adults (33%) say climate scientists understand “very well”

whether climate change is occurring, another 39% say scientists

understand this “fairly well” and some 27% say scientists don’t

understand this “too well” or don’t understand it at all. Just over a quarter of the public – 28% – says climate scientists have a solid understanding of the causes of climate change. And even fewer, 19%, of adults say the same about climate scientists’ understanding of the best ways to address climate change.

While Americans trust information from climate scientists more than that from other key players, fewer than half have “a lot” of faith that they are getting full and accurate information

Americans hold relatively positive views about climate scientists, compared with other groups, as credible sources of information. Far more Americans say they trust information from climate scientists on the causes of climate change than say they trust either energy industry leaders, the news media or elected officials. But in absolute terms, public trust in information from climate scientists is limited.

Some

39% of Americans say they trust climate scientists a lot when it comes

to providing information about the causes of climate change. About a

fifth of Americans (22%) hold no trust or not too much trust in

information from climate scientists. Another 39% report “some” trust in

climate scientists to give a full and accurate portrait of the causes of

climate change.

Some

39% of Americans say they trust climate scientists a lot when it comes

to providing information about the causes of climate change. About a

fifth of Americans (22%) hold no trust or not too much trust in

information from climate scientists. Another 39% report “some” trust in

climate scientists to give a full and accurate portrait of the causes of

climate change. Public trust in information from the news media, energy industry leaders and elected officials is significantly lower, however. A majority of Americans report having not too much or no trust in information from these groups about the causes of climate change.

Few say climate research findings reliably undergirded by the best available evidence; similar shares say other, more negative factors influence climate research

This survey included a series of questions that tapped into Americans’ beliefs of potential influences on climate research, and the findings suggest some skepticism and mixed assessments from the public. A minority of 32% of Americans say climate research is influenced by the best available evidence “most of the time,” 48% say this occurs some of the time and 18% take a decidedly skeptical view that the best evidence rarely or never influences research findings.

A

similar share of Americans say that scientists’ career aspirations

influence their research most of the time (36%). A smaller share of

adults say scientists’ political leanings (27%) or their desires to help

related industries (26%) influence climate research findings most of

the time. But majorities say these less germane motivations influence

results at least some of the time.

A

similar share of Americans say that scientists’ career aspirations

influence their research most of the time (36%). A smaller share of

adults say scientists’ political leanings (27%) or their desires to help

related industries (26%) influence climate research findings most of

the time. But majorities say these less germane motivations influence

results at least some of the time. While most Americans say the public’s best interest factors into climate change research at least some of the time, only 23% of Americans say climate research is influenced by concern for public interests most of the time. Overall, 28% say this occurs not too often or never and 48% of Americans take a middle position, saying this sometimes influences climate research findings.

Politics is the central factor shaping people’s beliefs about the effects of climate change, ways to address warming, trust in climate scientists

Why we include “leaners” in the Democratic and Republican groups

Throughout this report, Republicans and Democrats include independents and other non-partisans who lean toward the parties. Partisan leaners tend to have attitudes and opinions very similar to those of partisans. On questions about climate change and trust of climate scientists, there are wide differences between those who lean to the Democratic Party and those who lean to the Republican Party. And leaners and partisans of their party have roughly the same positions on these questions.

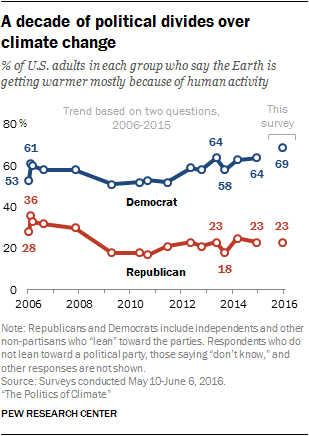

Political divides are dominant in public views about climate matters. Consistent with past Pew Research Center surveys, most liberal Democrats espouse human-caused climate change, while most conservative Republicans reject it. But this new Center survey finds that political differences over climate issues extend across a host of beliefs about the expected effects of climate change, actions that can address changes to the Earth’s climate, and trust and credibility in the work of climate scientists. People on the ideological ends of either party, that is liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans, see the world through vastly different lenses across all of these judgments.

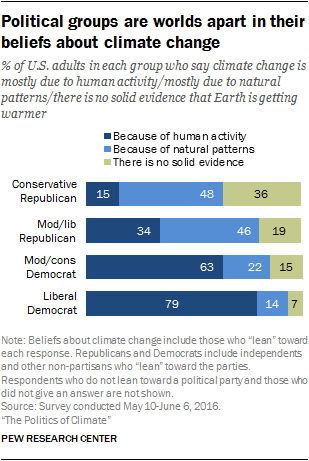

Political groups differ widely over beliefs about climate and ways to address warming

As with previous Pew Research Center surveys,

there are wide differences among political party and ideology groups on

whether or not human activity is responsible for warming temperatures. A

large majority of liberal Democrats (79%) believe the Earth is warming

mostly because of human activity. In contrast, only about one-in-six

conservative Republicans (15%) say this, a difference of 64 percentage

points. A much larger share of conservative Republicans say there is no

solid evidence the Earth is warming (36%) or that warming stems from

natural causes (48%).

As with previous Pew Research Center surveys,

there are wide differences among political party and ideology groups on

whether or not human activity is responsible for warming temperatures. A

large majority of liberal Democrats (79%) believe the Earth is warming

mostly because of human activity. In contrast, only about one-in-six

conservative Republicans (15%) say this, a difference of 64 percentage

points. A much larger share of conservative Republicans say there is no

solid evidence the Earth is warming (36%) or that warming stems from

natural causes (48%).  Pew Research Center surveys have found these kinds of wide political gaps in previous years. In the 2015 Center

survey, using somewhat different question wording, there was a

41-percentage-point difference between partisans; 64% of Democrats said

climate change was mostly due to human activity, compared with 23% among

Republicans.

Pew Research Center surveys have found these kinds of wide political gaps in previous years. In the 2015 Center

survey, using somewhat different question wording, there was a

41-percentage-point difference between partisans; 64% of Democrats said

climate change was mostly due to human activity, compared with 23% among

Republicans. Most liberal Democrats think negative effects from global climate change are likely

People’s

beliefs about the likely effects of climate change are quite uniformly

at odds across party and ideological lines. About six-in-ten or more of

liberal Democrats say it is very likely that climate change will bring

droughts, storms that are more severe, harm to animal and plant life,

and damage to shorelines from rising sea levels. By contrast, no more

than about two-in-ten conservative Republicans say each of these

possibilities is “very likely”; about half consider these possibilities

not too or not at all likely.

People’s

beliefs about the likely effects of climate change are quite uniformly

at odds across party and ideological lines. About six-in-ten or more of

liberal Democrats say it is very likely that climate change will bring

droughts, storms that are more severe, harm to animal and plant life,

and damage to shorelines from rising sea levels. By contrast, no more

than about two-in-ten conservative Republicans say each of these

possibilities is “very likely”; about half consider these possibilities

not too or not at all likely. There are more modest differences when it comes to people’s expectations that technological breakthroughs will solve climate problems in the future or that the American people will make major changes to their way of life as a result of climate change. A majority of Democrats think technological changes will help address climate change within the next 50 years; views among moderate/liberal Republicans are similar. Some 46% of conservative Republicans think this will probably or definitely occur. Similarly, about half of conservative Republicans (49%) expect Americans to make major changes to their way of life to address climate issues within the next five decades, as do majorities of other party and ideology groups.

Most conservative Republicans say each of six actions to address climate change would have small or negligible effects; most liberal Democrats believe each can make a big difference

There

is wide gulf between liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans

when it comes to beliefs about how to effectively address climate

change. Liberal Democrats are optimistic that a range of policy actions

can make “a big difference” in addressing climate change including:

power plant emission limits, international agreements about emissions,

tougher fuel efficiency standards for vehicles, and corporate tax

incentives to encourage businesses to reduce emissions resulting from

their activities. And, at least half of liberal Democrats say that both

personal efforts to reduce the carbon footprint of everyday activities

and more people driving hybrid and electric vehicles can make a big

difference in addressing global warming.

There

is wide gulf between liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans

when it comes to beliefs about how to effectively address climate

change. Liberal Democrats are optimistic that a range of policy actions

can make “a big difference” in addressing climate change including:

power plant emission limits, international agreements about emissions,

tougher fuel efficiency standards for vehicles, and corporate tax

incentives to encourage businesses to reduce emissions resulting from

their activities. And, at least half of liberal Democrats say that both

personal efforts to reduce the carbon footprint of everyday activities

and more people driving hybrid and electric vehicles can make a big

difference in addressing global warming. By contrast, conservative Republicans are largely pessimistic about the effectiveness of these options. Most conservative Republicans say each of these actions would make a small difference or have no effect on climate change. About three-in-ten or fewer conservative Republicans say each would make a big difference.

Most support a role for climate scientists in climate policy decisions, though political groups differ in relative priorities for scientists and the public in policy matters

More

than three-quarters of Democrats and most Republicans (69% among

moderate or liberal Republicans and 48% of conservative Republicans) say

climate scientists should have a major role in policy decisions related

to climate issues. Few in either party say climate scientists should

have no role in these policy decisions.

More

than three-quarters of Democrats and most Republicans (69% among

moderate or liberal Republicans and 48% of conservative Republicans) say

climate scientists should have a major role in policy decisions related

to climate issues. Few in either party say climate scientists should

have no role in these policy decisions. But there some differences among party and ideology groups in their relative priorities about this. Conservative Republicans give a higher comparative priority to the general public in policy decisions about climate change issues. Democrats and moderate/liberal Republicans prioritize a role for climate scientists.

Relative to other groups rated, fewer Americans think elected officials should have a major say in climate policy. Conservative Republicans stand out as being disinclined to support a major role for elected officials or leaders from other nations in climate policy.

There are wide opinion differences over whether scientists understand climate change

People’s

assessments of scientific understanding about climate also ties

strongly to their political perspectives. Most liberal Democrats rate

climate scientists as understanding “very well” whether climate change

is occurring (68%) and about half say scientists understand “very well”

the causes of climate change (54%). By contrast, just 11% of

conservative Republicans judge climate scientists as understanding very

well the sources of climate change. Fully 63% of this group says climate

scientists understand the causes of climate change “not too” or “not at

well.”

People’s

assessments of scientific understanding about climate also ties

strongly to their political perspectives. Most liberal Democrats rate

climate scientists as understanding “very well” whether climate change

is occurring (68%) and about half say scientists understand “very well”

the causes of climate change (54%). By contrast, just 11% of

conservative Republicans judge climate scientists as understanding very

well the sources of climate change. Fully 63% of this group says climate

scientists understand the causes of climate change “not too” or “not at

well.” Fewer in either party think climate scientists understand ways to address climate change. Some 36% of liberal Democrats say climate scientists understand this “very well” and 49% say scientists understand this “fairly well.” Conservative Republicans are particularly skeptical of climate scientists’ understanding of ways to address climate change; just 8% say scientists understand how to address climate change “very well,” 28% say “fairly well” and 64% rate scientific understanding of this as “not too well” or “not at all well.”

Liberal Democrats are most likely to see widespread agreement among climate scientists

American’s

perceptions of scientific consensus on climate change are also related

to political divides, as has also been found in past Pew Research Center

surveys.6

American’s

perceptions of scientific consensus on climate change are also related

to political divides, as has also been found in past Pew Research Center

surveys.6 Liberal Democrats are far more likely than any other party or ideology group to see strong consensus among climate scientists. Some 55% of liberal Democrats say almost all climate scientists agree that human behavior is mostly responsible for climate change.

Much smaller shares of other groups see widespread consensus among climate scientists. Some 29% of moderate/conservative Democrats say almost all climate scientists agree that human behavior is responsible for climate change, while some 16% of conservative Republicans and 13% of moderate/liberal Republicans say the same.

People’s perceptions of scientific consensus, even among liberal Democrats, are at odds with the near unanimity expressed in climate research publications that human activity is mostly responsible for climate change, however.7

Deep political divide over whether to trust information from climate scientists

Public

trust in information from climate scientists about the causes of

climate change varies widely among political groups. Seven-in-ten (70%)

liberal Democrats trust climate scientists a lot to provide full and

accurate information about this, another 24% report some trust in

information from climate scientists. In contrast, just 15% of

conservative Republicans say they trust climate scientists a lot to give

full and accurate information, four-in-ten (40%) report some trust and

45% have not too much or no trust in information from climate

scientists. Moderate or liberal Republicans and moderate or conservative

Democrats fall in the middle between these two extremes in their level

of trust.

Public

trust in information from climate scientists about the causes of

climate change varies widely among political groups. Seven-in-ten (70%)

liberal Democrats trust climate scientists a lot to provide full and

accurate information about this, another 24% report some trust in

information from climate scientists. In contrast, just 15% of

conservative Republicans say they trust climate scientists a lot to give

full and accurate information, four-in-ten (40%) report some trust and

45% have not too much or no trust in information from climate

scientists. Moderate or liberal Republicans and moderate or conservative

Democrats fall in the middle between these two extremes in their level

of trust. Liberal Democrats see the influences and motivations behind climate research findings in a mostly positive light; conservative Republicans are much more negative

American’s

judgments about the credibility of climate research findings are also

tied with people’s political party and ideological orientations. At

least half of liberal Democrats (55%) say climate research is influenced

by the best available evidence most of the time, and 39% say this

occurs some of the time. By contrast, just 9% of conservative

Republicans say the best evidence influences climate research most of

the time, though 54% say this occurs some of the time.

American’s

judgments about the credibility of climate research findings are also

tied with people’s political party and ideological orientations. At

least half of liberal Democrats (55%) say climate research is influenced

by the best available evidence most of the time, and 39% say this

occurs some of the time. By contrast, just 9% of conservative

Republicans say the best evidence influences climate research most of

the time, though 54% say this occurs some of the time. Conservative Republicans are particularly skeptical about the factors influencing climate research. Some 57% of conservative Republicans say climate research is influenced by researchers’ career interests most of the time and 54% say the scientists’ own political leanings influence research findings most of the time. A much smaller share of liberal Democrats say either of these factors influence scientific research most of the time, although many say scientists’ career interests or personal political leanings influence the findings some of the time (54% for each).

More than a third of Americans are deeply concerned about climate issues; their views about climate change and scientists differ starkly from the less concerned

The

public’s level of concern about climate matters varies. The Pew

Research Center survey finds 36% of Americans particularly concerned,

saying they care a great deal about the issue of global climate change.

An additional 38% express some interest, while 26% say they care not too

much or not at all about the issue of climate change.

The

public’s level of concern about climate matters varies. The Pew

Research Center survey finds 36% of Americans particularly concerned,

saying they care a great deal about the issue of global climate change.

An additional 38% express some interest, while 26% say they care not too

much or not at all about the issue of climate change. Not surprisingly, those who care a great deal about global climate change issues are more attentive to climate news. Some 26% of those who care about climate issues a great deal follow climate news reports very closely, compared with just 3% among those less concerned about these issues.

A profile of climate-engaged Americans

Those

most concerned about climate issues come from all gender, age,

education, race and ethnic groups. Those more concerned about climate

issues are slightly more likely to be women than men (55% vs. 45%). And,

they are more likely to be Hispanic than the population as whole.

Those

most concerned about climate issues come from all gender, age,

education, race and ethnic groups. Those more concerned about climate

issues are slightly more likely to be women than men (55% vs. 45%). And,

they are more likely to be Hispanic than the population as whole. Politically, those who care more deeply about climate issues tend to be Democrats. They include about equal shares of moderate or conservative Democrats (37%) and liberal Democrats (35%). Some 24% are Republicans.

Those most concerned about climate issues hold beliefs that differ starkly from those who are less concerned

Political

party affiliation and ideology are not the only factors that shape

people’s views about climate issues and climate scientists. People who

say they care a great deal about this issue are far more likely to

believe the Earth is warming because of human activities, to believe

negative effects from climate change are likely, and that proposals to

address climate change will be effective. This group also holds more

positive views about climate scientists and their research, on average.

Differences between those more concerned and less concerned occur among

both Republicans and Democrats.

Political

party affiliation and ideology are not the only factors that shape

people’s views about climate issues and climate scientists. People who

say they care a great deal about this issue are far more likely to

believe the Earth is warming because of human activities, to believe

negative effects from climate change are likely, and that proposals to

address climate change will be effective. This group also holds more

positive views about climate scientists and their research, on average.

Differences between those more concerned and less concerned occur among

both Republicans and Democrats. About three-quarters of Americans who care deeply about climate change say the Earth is warming because of human activity (76%), this compares with 48% among those who care some and just 10% among those who do not care at all or not too much about this issue.

Differences between those who care more and less about climate change issues occur among both Republicans and Democrats. Some 44% of Republicans who care a great deal about climate issues believe human behavior is causing temperatures to rise, compared with just 17% of Republicans who care some or less about this issue. Similarly, among Democrats, 87% of those who care a great deal about climate issues believe human activity is mostly responsible for global climate change, compared with 52% among those who care some or less about the issue of climate change.

Large majorities of those who care most about this issue think it is very likely that climate change will hurt the environment. Roughly three-quarters of those deeply concerned about climate issues think climate change will very likely bring harm to animal life (74%), damage to forests and plants life (74%), more droughts (73%), more severe storms (74%), and damage to shorelines from rising sea levels (74%). By contrast, roughly a third of those who care “some” about this issue say each of these possible effects is very likely. Many of those who do not care at all or not too much about the issue of climate change say the evidence of warming is uncertain; this group is particularly skeptical that any of these harms will come to pass. Differences among the more and less concerned about climate issues occur both among Republicans and Democrats alike.

There are smaller differences when it comes to people’s expectations that Americans will make major changes to their way of life in order to address climate change. About two-thirds of those who care a great deal about climate issues (67%) expect this to occur within the next 50 years, as does a similar share of those who care some about this issue (70%) and 42% of those who do not care at all or not too much about the issue of climate change. And, 63% of the more climate-engaged Americans expect new technological solutions to address most problems stemming from climate change. Those who care some about climate issues hold similar views; 62% expect technological solutions. Those who have little personal concern about the issue of climate change are more skeptical; 34% expect technological solutions, 64% do not.

People who are especially concerned about climate issues are optimistic that both policy and personal efforts can be effective at addressing climate change

Majorities of climate-engaged Americans are optimistic that a range of both policy and individual actions can make a big difference in addressing climate change. Those less personally concerned about climate issues are considerably more pessimistic, by comparison.

About eight-in-ten of those more deeply concerned about climate issues say restrictions on power plant emissions (80%) and an international agreement to limit carbon emissions (78%) can make a big difference in addressing climate change. Some 73% of this group says tougher fuel efficiency standards for cars and trucks can make a big difference, and seven-in-ten (70%) say the same about corporate tax incentives to encourage businesses to reduce the carbon emissions stemming from their activities. By contrast, no more than two-in-ten American who are not at all or not too personally concerned about climate issues think each of these policy actions can make a big difference, although a sizeable minority among this group says each can make a small difference. Those who care “some” about the issue of climate change fall in between these two extremes; roughly four-in-ten of this group say each of these policy actions can make a big difference; a roughly similar share says each can make a small difference.

The same pattern occurs when it comes to individual efforts to address climate change. Among those who care deeply about climate issues, 63% believe individual efforts to reduce the “carbon footprint” linked with one’s daily activities can make a big difference. Among those who care some about this issue, about half as many say this can make a big difference (33%), and most (58%) say it can make a small difference. Just 12% of those with little personal concern about climate change say individual efforts of this sort can make a big difference, 42% says this can make a small difference, and 43% says this will have almost no effect. Similarly, some 63% of those personally concerned about climate issues say more people driving hybrid and electric vehicles can make a big difference in addressing climate change, compared with 40% among those who care some about climate issues and just 13% among those who do not care at all or not too much about climate issues.

Climate-engaged public is far more likely to trust climate scientists’ information and understanding of climate issues, see climate research findings as rooted in the evidence

People

who care more deeply about climate issues are also more likely than

others in the general public to see climate scientists’ and their work

in a positive light.

People

who care more deeply about climate issues are also more likely than

others in the general public to see climate scientists’ and their work

in a positive light. Nearly all (90%) Americans who are deeply concerned about climate change issues support a major role for climate scientists in related policy decisions, as do 68% of Americans with some personal concern about climate issues. About a third (34%) of those with not too much or no personal concern about climate issues say climate scientists should have a major role, and 41% say scientists should have a minor role in climate policy.

This pattern holds among both Democrats and Republicans. For example, some 87% of Republicans who care a great deal about climate issues say climate scientists should have a major role in climate policy. This compares with 48% among other Republicans.

Those who care a great deal about climate issues are much more likely than other Americans to say climate scientists understand very well whether change is occurring (64% vs. 23% among those care some and 7% among those do not care at all or not too much about this issue). About half of those deeply concerned about climate issues (52%) say climate scientists understand very well the causes of climate change, compared with just 19% among those with some personal concern and just 8% among those with no or not too much personal concern about this issue.

More Americans who care a great deal about climate issues say scientists understand the best ways to address climate change very well (37%) or fairly well (48%). Many fewer of less climate-concerned adults say the same. Just 13% of those with some personal concern about climate issues say scientists understand very well how to address climate change, while 56% say scientists understand this fairly well. And, just 5% of those with no or little personal concern about climate issues say scientists understand very well how to address climate change, 25% say scientists understand this fairly well and 68% say scientists do not understand this at all or not too well. Differences over climate scientists’ understanding occur among both Democrats and Republicans who are relatively more and less concerned about climate change.

Similarly, people who care more about climate issues are more inclined to see consensus among scientists about the causes of climate change. Some 48% of the climate-concerned public says that almost all climate scientists agree that human activity is responsible for climate change; this compares with just 19% saying almost all scientists agree about this among those who care some about climate issues and 12% among those who do not care at all or not too much about climate issues.

Two-thirds of Americans deeply concerned about climate issues trust information from climate scientists

Those more concerned about global climate issues are far more trusting of information from climate scientists than are those less concerned about these issues. Two-thirds of the public who cares a great deal about climate issues (67%) say they trust climate scientists a lot to provide full and accurate information on the causes of global climate change. In contrast, 33% of those who care some about climate issues trust scientists’ information a lot, while 53% trust it some. Just 9% of those with little or no personal concern about climate issues trust scientists’ information a lot, 36% trust it some and 55% have not too much or no trust in information from climate scientists about this.

Democrats and Republicans who care a great deal about climate issues are more than twice as likely as their fellow partisans to hold a lot of trust in information from climate scientists. Among Republicans who care about climate issues, 46% trust climate scientists’ information a lot compared with 16% among other Republicans. Among Democrats, fully 76% of those who care about climate issues a great deal say they trust climate scientists’ information a lot compared with 34% among other Democrats.

Those deeply concerned about climate issues are more inclined to see research findings as rooted in the best available evidence, fewer say other motives of scientists underlie the research findings

Americans who are more concerned with climate issues are inclined to think research findings on climate are influenced by the best available evidence; about half of this group (51%) says research is influenced by the best evidence most of the time and 39% say this occurs some of the time. In contrast, three-in-ten (30%) of those with some personal concern about climate issues say the best evidence influences climate research findings most of the time, 60% say this occurs some of the time. Just 9% of those with no or not too much personal concern about climate issues say the best evidence influences climate research findings most of the time, 42% say this occurs some of the time and 45% say this occurs not too often or never.

By the same token, there are similar differences in views about negative influences on research between those who care deeply about climate issues and those who do not; the climate-concerned public is less inclined to see such research as influenced by scientists’ personal political leanings, a desire to help their industries or their careers.

Public views of news coverage about global climate change

The

news media are a key source of information about climate issues. The

Pew Research Center survey finds only a small minority (11%) of

Americans follow news about climate matters very closely. Another 44%

follow somewhat closely, and an equal share follows news not too (32%)

or not at all closely (12%).

The

news media are a key source of information about climate issues. The

Pew Research Center survey finds only a small minority (11%) of

Americans follow news about climate matters very closely. Another 44%

follow somewhat closely, and an equal share follows news not too (32%)

or not at all closely (12%). Overall, Americans are closely divided in their assessments of media coverage on climate issues. Some 47% say the news media do a very or somewhat good job, while 51% say they do a bad job covering climate issues.

These findings stand in contrast to American’s views about the media overall. As shown elsewhere in this report, just 5% say they have a great deal of confidence in the news media, generally, to act in the public interest. A 2013 Pew Research Center report documents the steep decline in public regard for media accuracy, fairness and independence over the past two decades.

These findings stand in contrast to American’s views about the media overall. As shown elsewhere in this report, just 5% say they have a great deal of confidence in the news media, generally, to act in the public interest. A 2013 Pew Research Center report documents the steep decline in public regard for media accuracy, fairness and independence over the past two decades. People who say they closely follow climate news tend to give the media somewhat higher marks for coverage in this area as do those who say care a great deal about climate issues.

Public

views about media performance also tend to divide along political

lines. Conservative Republicans are especially critical of media

coverage on climate issues with 71% of this group saying the media do a

bad job. Moderate and liberal Republicans are closely divided in their

overall evaluations of news coverage on climate (47% say they do a good

job and 52% say they do a bad job). The balance of opinion is more

positive among moderate and conservative Democrats (64% good to 34% bad)

though liberal Democrats are closely divided (48% to 51%) on this

issue. This pattern is broadly consistent with other Pew Research Center studies on views of the media.

Public

views about media performance also tend to divide along political

lines. Conservative Republicans are especially critical of media

coverage on climate issues with 71% of this group saying the media do a

bad job. Moderate and liberal Republicans are closely divided in their

overall evaluations of news coverage on climate (47% say they do a good

job and 52% say they do a bad job). The balance of opinion is more

positive among moderate and conservative Democrats (64% good to 34% bad)

though liberal Democrats are closely divided (48% to 51%) on this

issue. This pattern is broadly consistent with other Pew Research Center studies on views of the media. The public divide over media performance in this area could link to the balance of coverage on climate issues. The Pew Research Center survey included two additional questions exploring people’s views about news coverage.

Overall,

some 35% of Americans say the media exaggerate the threat from climate

change while a roughly similar share (42%) of adults says the media do

not take the threat seriously enough. Two-in-ten (20%) adults says the

media are about right in their reporting about climate.

Overall,

some 35% of Americans say the media exaggerate the threat from climate

change while a roughly similar share (42%) of adults says the media do

not take the threat seriously enough. Two-in-ten (20%) adults says the

media are about right in their reporting about climate.  The

same pattern occurs on a question about the balance of attention to

those skeptical of climate change. Four-in-ten (40%) adults say the

media give too little attention to skeptics, while a slightly smaller

share (32%) says the media give skeptics too much attention. A quarter

of Americans (25%) say the media are about right in their coverage of

those skeptical about climate change.

The

same pattern occurs on a question about the balance of attention to

those skeptical of climate change. Four-in-ten (40%) adults say the

media give too little attention to skeptics, while a slightly smaller

share (32%) says the media give skeptics too much attention. A quarter

of Americans (25%) say the media are about right in their coverage of

those skeptical about climate change.  In

keeping with the wide political divides on beliefs about climate

issues, there are strong political differences in views about media

coverage of climate change. A majority of conservative Republicans (72%)

say the media exaggerate the threat of climate change, while some 64%

of liberal Democrats say the media do not take the threat seriously

enough.

In

keeping with the wide political divides on beliefs about climate

issues, there are strong political differences in views about media

coverage of climate change. A majority of conservative Republicans (72%)

say the media exaggerate the threat of climate change, while some 64%

of liberal Democrats say the media do not take the threat seriously

enough. Opinions about media coverage of skeptics follow a similar pattern. Some 59% of conservative Republicans say the media give too little attention to skeptics of climate change. In contrast, about half of liberal Democrats (54%) say the media give too much attention to skeptics of climate change.

Public opinion on renewables and other energy sources

Americans’ concerns about climate change have put energy production of fossil fuels and the carbon gases these fuels emit at the center of public discussions about climate and the environment. Those debates coupled with long-standing economic pressures to decrease reliance on other countries for energy needs have raised attention to renewable forms of energy including solar and wind power.

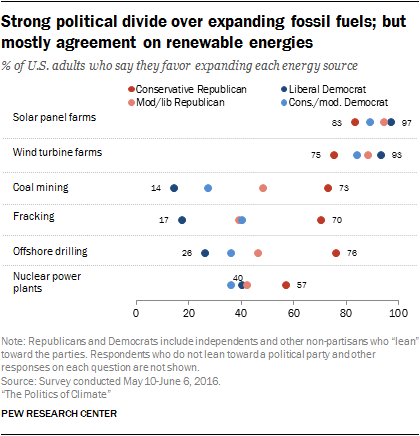

Public opinion about energy issues is widely supportive of expanding both solar and wind power but more closely divided when it comes to expanding fossil fuel energies such as coal mining, offshore oil and gas drilling, and hydraulic fracturing for oil and natural gas. While there are substantial party and ideological divides over increasing fossil fuel and nuclear energy sources, strong majorities of all party and ideology groups support more solar and wind production.

Most Americans know the U.S. is producing more energy today

Most Americans are aware of America’s ongoing energy boom.

The United States is producing more energy from fossil fuels and has

ticked up production of renewable sources such as wind and solar. A

large majority of Americans (72%) say the United States is producing

more energy than it did 20 years ago. Far smaller shares say the U.S. is

producing the same level (17%) or less energy (10%) than it did 20

years ago8

Most Americans are aware of America’s ongoing energy boom.

The United States is producing more energy from fossil fuels and has

ticked up production of renewable sources such as wind and solar. A

large majority of Americans (72%) say the United States is producing

more energy than it did 20 years ago. Far smaller shares say the U.S. is

producing the same level (17%) or less energy (10%) than it did 20

years ago8 Majorities across demographic, educational and political groups say the U.S. is producing more energy today. Awareness of this trend is especially high among those with postgraduate degrees (86% compared with 64% among those with high school degrees or less). Men are more inclined to say the U.S. is producing more energy than women (79% vs. 66%), while Democrats are modestly more likely than Republicans to say this (79% vs. 65%).

Strong public support for more wind and solar, closer divides over nuclear and fossil fuels

Large

majorities of Americans favor expanding renewable sources to provide

energy, but the public is far less supportive of increasing the

production of fossil fuels, such as oil and gas, and nuclear energy.

Large

majorities of Americans favor expanding renewable sources to provide

energy, but the public is far less supportive of increasing the

production of fossil fuels, such as oil and gas, and nuclear energy. Fully 89% of Americans favor more solar panel farms, just 9% oppose. A similarly large share supports more wind turbine farms (83% favor, 14% oppose).

By comparison, the public is more divided over expanding the production of nuclear and fossil fuel energy sources. Specifically, 45% favor more offshore oil and gas drilling, while 52% oppose. Similar shares support and oppose expanding hydraulic fracturing or “fracking” for oil and gas (42% favor and 53% oppose). Some 41% favor more coal mining, while a 57% majority opposes this.

And, 43% of Americans support building more nuclear power plants, while 54% oppose. Past Pew Research Center surveys on energy issues, using somewhat different question wording and survey methodology, found opinion broadly in keeping with this new survey. For example, the balance of opinion in a 2014 Pew Research Center survey about building more nuclear power plants was similar (45% favor, 51% oppose), and some 52% of Americans favored and 44% opposed allowing more offshore oil and gas drilling in that survey.

Most Republicans and Democrats favor expanding renewables; there are strong divides over expanding fossil fuels

Across the political spectrum, large majorities support expansion of solar panel and wind turbine farms. Some 83% of conservative Republicans favor more solar panel farms; so, too, do virtually all liberal Democrats (97%). Similarly, there is widespread agreement across party and ideological groups in favor of expanding wind energy.

Consistent with past Pew Research Center surveys,

this new survey finds there are deep political divides over expanding

fossil fuel energy sources. Conservative Republicans stand out from

other party and ideology groups in this regard. At least seven-in-ten

conservative Republicans support more coal mining (73%), fracking (70%)

and offshore drilling (76%). A majority of Democrats oppose expanding

each of these energy sources while moderate/liberal Republicans fall

somewhere in the middle on these issues.

Consistent with past Pew Research Center surveys,

this new survey finds there are deep political divides over expanding

fossil fuel energy sources. Conservative Republicans stand out from

other party and ideology groups in this regard. At least seven-in-ten

conservative Republicans support more coal mining (73%), fracking (70%)

and offshore drilling (76%). A majority of Democrats oppose expanding

each of these energy sources while moderate/liberal Republicans fall

somewhere in the middle on these issues. The political divide over expanding nuclear energy is smaller. Some 57% of conservative Republicans, and 51% of all Republicans, favor more nuclear power plants. Democrats lean in the opposite direction with 59% opposed and 38% in favor of more nuclear power plants.

As also found in past Pew Research Center surveys, women are less supportive of expanding nuclear power than men, even after controlling for politics and education. Some 34% of women favor and 62% oppose more nuclear plants. Men are more closely divided on this issue: 52% favor and 46% oppose. Men and women hold more similar views on other energy issues.

Many Americans are giving serious thought to having solar panels at home

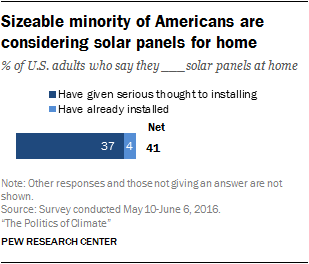

America’s solar power industry is growing. In 2016, solar is expected to add more electricity generating capacity

than any other energy source in the United States. Just 4% of Americans

report having home solar panels but many more − 37% − say they are

giving it serious thought.

America’s solar power industry is growing. In 2016, solar is expected to add more electricity generating capacity

than any other energy source in the United States. Just 4% of Americans

report having home solar panels but many more − 37% − say they are

giving it serious thought. These figures are similar among homeowners. Some 44% of homeowners have already installed (4%) or have given serious thought to installing (40%) solar panels at home.

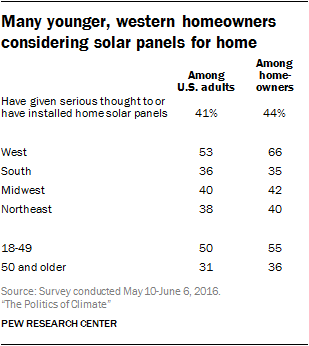

Western

residents and younger adults are especially likely to say are

considering, or have installed, solar panels at home. Some 14% of

homeowners in the West have installed solar panels at home and another

52% say they are considering doing so. By contrast, 35% of homeowners in

the South say they have installed (3%) or given serious thought to

installing solar at home (33%).

Western

residents and younger adults are especially likely to say are

considering, or have installed, solar panels at home. Some 14% of

homeowners in the West have installed solar panels at home and another

52% say they are considering doing so. By contrast, 35% of homeowners in

the South say they have installed (3%) or given serious thought to

installing solar at home (33%). Some 55% of homeowners under age 50 say they have given serious thought to installing or have already installed solar panels at home. Fewer homeowners ages 50 and older say the same (36%).

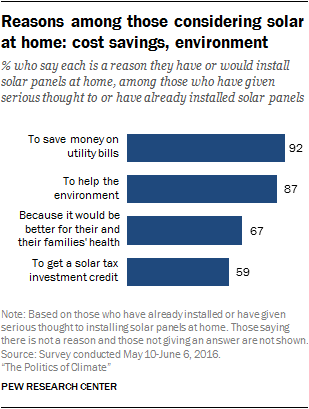

The

key reasons people cite for considering solar are financial followed by

concern for the environment. Among all who have installed or given

serious thought to installing solar panels, large majorities say their

reasons include cost savings on utilities (92%) or helping the

environment (87%). Smaller shares of this group, though still

majorities, say improved health (67%) or a solar tax investment credit

(59%) are reasons they have or would install home solar panels.

The

key reasons people cite for considering solar are financial followed by

concern for the environment. Among all who have installed or given

serious thought to installing solar panels, large majorities say their

reasons include cost savings on utilities (92%) or helping the

environment (87%). Smaller shares of this group, though still

majorities, say improved health (67%) or a solar tax investment credit

(59%) are reasons they have or would install home solar panels.