The answer could have long-term consequences for both wunderkinds.

In

early 2017, Mark Zuckerberg was gaming out his personal challenge for

the year—an epic listening tour to meet with Americans from every state

in the U.S. The Facebook CEO hadn’t checked off Indiana yet, but he had

an idea where he wanted to go. He just needed help with the execution.

Zuckerberg reached out via his preferred method of

communication—Facebook Messenger—to a fellow Harvard alum who after

leaving Cambridge, had eventually returned to his South Bend roots and

become a successful local politician. He got no response. So he turned

to an old Harvard dorm-mate named Joe Green, asking for an introduction.

Green, who lives in Los Angeles where he

builds co-living spaces and

funds psychedelic research,

and Zuckerberg had stayed in close touch over the years. “We were

talking,” Green said to me, recounting the conversation which has not

been reported before, “and he said, ‘Hey, do you know Pete Buttigieg?’

And I was like, yeah, of course, super well.’”

And so Green let

Buttigieg know that Zuckerberg was trying to get in touch. “I told

Peter, ‘Hey, I’m going to introduce you to Mark Zuckerberg,’ and he had

to change his Facebook settings” to be able to get the CEO’s note to

him.

Some weeks later, on a dreary day in April, Zuckerberg and

Buttigieg were sitting in the mayor’s Jeep as Zuckerberg fiddled with

the Facebook Live video stream. Buttigieg, wearing a too-big bomber

jacket, gave his famous guest a tour of the Rust Belt city, gamely

describing the city’s revival—how an old Studebaker factory site was

being repurposed into a data center, how downtown’s one-way streets had

been redesigned to slow city traffic and foster human connection. They

stopped for coffee at a pay-it-forward place, and had lunch at a

family-owned tavern in a largely Latino, working-class part of the city.

One of Zuckerberg’s spokespeople described the pair as “friends” to the

local reporters who were there to chronicle this visitation from the

world’s most powerful social media executive.

But this was not a

reunion of college buds. In fact, it was more like the beginning of a

relationship that has evolved in unexpected ways over the past three

years as these two precociously talented and ambitious young men have

asserted themselves on the national stage.

Zuckerberg, class of

2006, and Buttigieg, class of 2004, overlapped for two years at Harvard

but ran in largely separate circles. Zuckerberg was a Phillips Exeter

kid from Westchester, New York, obsessed with building computer games

and proto-networking tools. Buttigieg was student body president at the

co-ed Roman Catholic St. Joseph’s High School, a Midwesterner with a

deep interest in public service who’d applied to Harvard sight unseen.

Zuckerberg and Buttigieg wouldn’t meet, and then only fleeting, until

the 2012 New York wedding of another mutual Harvard friend: Facebook

co-founder Chris Hughes.

At the time their paths crossed for a

few hours in South Bend, Zuckerberg was struggling to defend himself and

his company against growing blowback over the 2016 U.S. presidential

election. Some wondered if this tour wasn’t laying groundwork for a

presidential run of his own. Buttigieg, meanwhile, had only recently

fallen short in his bid to become chairman of the Democratic National

Committee. Hosting the tech luminary was a helpful shot of positive

national publicity at a moment when he was beginning to explore his

options for wider office.

Now three years later, their

relationship is the subject of ramped-up speculation and interest.

Zuckerberg is still one of the technology world’s most powerful figures,

but his half-trillion-dollar company is facing unprecedented threats,

as calls grow to break it apart. And, surprisingly, it’s Buttigieg who

has mounted a top-tier presidential campaign.

And suddenly, the

connection between Zuckerberg and Buttigieg, as tenuous as it might be,

matters for both men—and for the country. Politically, beating up on

tech firms has become a winning populist move. But tech leaders can

still be powerful and wealthy allies—and in an election stuffed with

aging Boomers, there’s also appeal in the idea of a digital-native

leader who can bring tech giants to the table and speak to them in their

own language.

For now, Buttigieg seems to be keeping the tech world close but Facebook at a distance.

Buttigieg

has drawn considerable financial support from Silicon Valley

for his White House bid, and Zuckerberg and his wife drew headlines

when they recommended staffers to the campaign. But Buttigieg has in

recent months begun to speak out more forcefully about the need to

constrain the power of both Facebook and Zuckerberg. In the midst of a

massively consequential election that could hinge in no small measure on

the decisions Zuckerberg makes about how his platform handles political

ads, their relationship is evolving—and not necessarily in a friendlier

way. In

an interview with the New York Times editorial board

in January. Buttigieg criticized what he called Facebook’s “refusal to

accept their responsibility for speech that they make money from.”

The

Buttigieg campaign says that the two haven’t spoken for a year and a

half, a characterization Facebook doesn’t dispute. Buttigieg said a year

ago that he and Zuckerberg have been in touch “every now and then,” but

clarified Sean Savett, a Buttigieg campaign spokesperson, “They haven’t

talked in over a year, or since, really, Pete’s run for president.”

Back

in the mid-aughts, Zuckerberg was holed up in his dorm at a desk

scattered with empty Snapple bottles, building, first, FaceMash, a site

for ranking the attractiveness of his classmates, and then

TheFacebook.com. Buttigieg, meanwhile, was

angling to win election

as president of Harvard’s Institute of Politics, the Kennedy

family-endowed center that lets service-minded undergrads rub shoulders

with political luminaries. Buttigieg got onto Facebook as

one of the

first few hundred users—

facebook.com/287 still redirects to one of Buttigieg’s profiles—but he later recalled to

New York Magazine, “I thought it was just another Harvard thing. We didn’t realize where it was going.”

Quickly,

though, the scale and ambition of what Zuckerberg was up to would

become clear. Facebook launched on February 4, 2004, and by December, it

had grown beyond Harvard, and beyond the Ivies altogether, amassing

more than a million users. A Harvard friend of Zuckerberg says that what

Mark had pulled off, at age 19, quickly became an inspiration on

campus. If Mark can conquer the Internet, what world changing can the

rest of us get busy doing? “There was this draw—that it was such a huge

success that it was like, ‘Oh, I can do that, too,’” says the friend,

Sam Lessin, who went on to spend four years at Facebook, ending up as

the vice president of product management. “It was part of the

atmosphere.”

But while Zuckerberg was, in those days, on the cusp

of changing the world, he had little interest in doing it through

traditional means. “After [the] summer of ’03, I thought social

networking should be applied to politics,” Joe Green said in an

interview in 2007. He says he pitched his college dormmate on the idea.

“Instead he built Facebook. That was clearly a bad choice,” Green joked.

“He asked me to be his partner,” Green said. “I instead went to work for [John] Kerry.”

It was the summer of 2004, and Zuckerberg, who’d had

run-ins with Harvard administrators

over copying photos from the school’s network to build FaceMash,

decided to drop out of the university and make a go of his site out in

California. Buttigieg, 22, had graduated, and was eager to get some

experience out on the campaign trail. Green, 21, was still wrestling

with his decision (under some pressure from his father) to not go west

with Zuckerberg, who didn’t seem especially contrite over the FaceMash

episode. (Zuckerberg would

later

laughingly recall that during the dramatic night in his Kirkland House

dorm room when he was scrambling to deal with the FaceMash aftermath,

“Joe comes in and takes our last Hot Pocket.”) In a move that might have

cost him hundreds of millions of dollars, Green joined a crew of

politicos being put together by Mike Moffo, whose brother Chris had gone

to Harvard, to work on Democratic presidential nominee John Kerry’s bid

to pull off an unlikely primary win in Arizona.

Arizona was a

third-tier state for Kerry, and thus an opening for aspiring but

inexperienced politics junkies. Housed in the squat state-party

headquarters in Phoenix “that lost Internet every time it rained,”

recalls Kate Gallego, the Arizona for Kerry campaign has gained over

time a reputation as an all-star squad. Gallego (Harvard ’04), who

worked on legislative issues for the state party, is now mayor of

Phoenix. Rohit Chopra (Harvard ’04) was deputy field director and one of

Green’s bosses; he’s now a commissioner on the Federal Trade

Commission. Moffo would go on to be deputy field director for the

successful 2008 Obama campaign. Doug Wilson was the state director; he

now is a foreign policy lead for the Buttigieg campaign.

But

even among that crew, Buttigieg, who worked on research and

communications for the campaign, had an aura. “You got the impression

that he was a total rock star,” says Jesse Gabriel, now a California

assembly member. “He was very serious, very thoughtful, and he just had a

gravitas about him in a way that struck me that he was going to go onto

big things.”

Green, meanwhile, was field organizing out in Lake

Havasu City, a Spring Break spot on the Colorado River in rural Arizona.

Says Gabriel of Green, “he was this sort of lovable and crazy guy. He

always had wild stories and was getting into all kinds of weird

situations. I think he was living in an underground bunker part of the

time. But Joe is also deeply intellectual, and very, very smart.” (Green

confirms he did spend part of the time living subterraneanly.)

Still,

Green and Buttigieg, however odd a pair they were, stayed close. Says

Gabriel, “they’re the kind of guys who could, you know, have a beer and

talk de Tocqueville.”

Arizona grew out of reach for Kerry and the band broke up.

Buttigieg

would go build his résumé, first at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar and

later as a McKinsey consultant based out of Chicago before heading home

to South Bend. Green would return to Harvard, spending years as a

startup founder working on the

idea that social networks could be used for politics.

It was a truth proven when Chris Hughes—a friend of Buttigieg’s and a

roommate of Zuckerberg’s who had, after graduating, headed west with

Zuckerberg to launch Facebook—left the company in 2007 to join the Obama

campaign. Hughes built

MyBarackObama.com,

using the social tools he learned at Zuckerberg’s side, to recruit and

deploy thousands of supporters, as well as fundraise millions of

dollars. Asked about it at the time,

Obama said, “there’s no more powerful tool for grassroots organizing than the Internet.”

Meanwhile,

Zuckerberg was turning Facebook into a global behemoth and transforming

himself, despite his professed lack of interest in politics, into a

person with considerable political clout. By 2011, with Facebook at more

than 750 million users, Zuckerberg was dining with President Obama and

other Silicon Valley leaders decades his senior, and hosting a convivial

mock town hall with Obama at Facebook’s California headquarters. In

2013, Zuckerberg’s eye began turning more intentionally toward politics

and policy. He launched

Fwd.us, a

pro-immigration group, and installed Green as its head. Zuckerberg’s

name was known all over the world, and his star was ascendant.

Buttigieg,

meanwhile, had a less eye-catching trajectory. In 2010, he had run for

Indiana state treasurer and lost, though the next year he rebounded to

win a race for mayor of his hometown—a humble city of a little over

100,000 people. He began building a reputation a forward-looking

politician dedicated to creatively repurposing his Rust Belt city. One

source of inspiration: Facebook. In

a TED talk at Notre Dame

during his first term, Buttigieg cited the site as an example of

turning something old—a student directory—into something innovative.

(Zuckerberg, he said, was “just a guy in the next dorm over from mine, a

guy who now has a lot more money than I do.”) Buttigieg won reelection

in 2015, and two years later he launched a long-shot bid to head the

Democratic National Committee, a party organization still rocked by

Donald Trump’s once-unthinkable presidential victory.

By late

February, it was clear that Buttigieg wasn’t going to win the DNC race,

and so he dropped out. Then Zuckerberg himself came calling.

For

years, Zuckerberg had dedicated himself to annual challenges. One year,

it was learning Mandarin. Another, eating only meat from animals he had

personally killed and butchered.

At the start of 2017,

Zuckerberg declared

that he intended to meet that year with people from all 50 U.S. states.

No more virtual connection, he would do it in person … sort of like a

politician. Immediately, the pledge raised speculation that Zuckerberg

was laying the groundwork for a national campaign of his own. Those

close to Zuckerberg insisted that wasn’t the case; concern over

so-called fake news on Facebook its role in swaying the 2016

presidential election was growing into anger, and Zuckerberg was trying

to come to terms with the social and political impact of the site he’d

always approached with the cool detachment of an engineer.

Zuckerberg

said as much. “After a tumultuous last year, my hope for this challenge

is to get out and talk to more people about how they're living, working

and thinking about the future,” he wrote in a blog post announcing the

project. Zuckerberg went on to say that, in his judgment, the forces of

technology and globalization have “contributed to a greater sense of

division than I have ever felt in my lifetime,” and “we need to find a

way to change the game so it works for everyone.”

Zuckerberg started

his year of travel

in Texas, where he met with local police in Dallas, went to the rodeo

in Fort Worth, and ate with community leaders in Waxahachie. During a

later, Southern tour, he visited a shrimp boat in Alabama, walked a

Civil War battlefield in Mississippi, and took in New Orleans’ Ninth

Ward. He visited a South Carolina church that had been terrorized by a

mass shooting and drove NASCAR in North Carolina. As winter turned to

spring, Zuckerberg’s team was eyeing a Midwest swing, and Indiana was

still on his to-be-visited list. It was then that Zuckerberg got in

touch with Buttigieg, albeit through Green, who had turned into a

liaison for Zuckerberg to the political world. Buttigieg, Green

discovered, may have been an admirer of Zuckerberg, but that didn’t

necessarily mean he was some kind of super-user. “I don’t think he was

the most active social-media person,” Green says.

During the

Saturday visit, Buttigieg drove, and Zuckerberg rode shotgun in the

mayor’s Jeep, with the Facebook CEO attempting, with some trouble, to

provide real-time video of their travels using Facebook Live. (Live

commentators asked why it looked like Buttigieg was on the right side of

the car; Zuckerberg, looking a bit chastened, explained that Facebook

Live flips its feed.) Buttigieg was the star, with Zuckerberg teeing up

questions like, “Pete, do you want to just give a bit of your

background, and how you came to be mayor here?”

They hit a

community-run coffee shop and a juvenile justice center, toured some of

Buttigieg’s “smart streets” project sites, and drove by the city’s old

Studebaker factory. They lunched at Simeri’s Old Town Tap, where the

pair enjoyed the $3.95 bowl of “Famous Hungarian Goulash,” a server at

the bar told me. Zuckerberg was gone by evening, off to have dinner with

firefighters in the nearby town of Elkhart.

Buttigieg

tweeted out a link to a local news story on Zuckerberg’s visit, commenting, “You know, another day in South Bend…”

That visit seems almost quaint now.

Not

long afterward, anger at Facebook would bubble over, with Zuckerberg

personally coming under fire for the idea that he looked the other way

while Russian actors used his social network to corrupt the 2016

election. That controversy fed others, and the outrage directed at the

company in political circles has only grown in the years since. Trump

and others on the right routinely accuse Facebook of being in the tank

for liberals—seemingly as a way of keeping the company on its toes.

Meanwhile, many on the left have developed real ire toward Facebook over

its policy of allowing misleading political ads and posts on its site,

which they view as kowtowing to Trump.

That was the context in which

the news came in October that Zuckerberg and his wife, the pediatrician and philanthropist Priscilla Chan, had

recommended two staffers

to the Buttigieg campaign. All involved sought to downplay the

situation. On a press call shortly afterward, Zuckerberg said it would

be a mistake to take it as some sort of endorsement, saying, “this

probably should not be misconstrued as if I’m, like, deeply involved in

trying to support their campaign or something like that.”

Sean

Savett, the Buttigieg campaign spokesman, said Zuckerberg and Chan

reached out to the campaign to recommend the staffers—one a data

scientist from Facebook, one an Indiana native from their

Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative—after they expressed interest in working for

Buttigieg. “That’s a pretty standard thing—you know, if you want to work

for a campaign, you try to use all of the levers and networks that are

possible.”

“A lot of people were like, ‘Oh my god, Mark and

[Priscilla] are doing HR for the campaign,’” says Savett. “He sent a

recommendation email, and his wife sent a recommendation email for two

people they knew who were applying, like pretty much any former boss

would if you were on good terms,” Savett says. “And they didn’t even

reach out to Pete for that. They reached out to one of Pete’s aides,”

campaign manager Mike Schmul, who Zuckerberg had met on his South Bend

visit.

But Facebook, by that point, had become politically toxic

in some quarters, and Zuckerberg’s dabbling in politics had become

fraught.

Even some of those once closest to the company have turned on it.

Facebook

made Chris Hughes rich, with his net worth reportedly nearing a

half-billion dollars. But today he’s one of the company’s harshest

critics,

calling for the company to be broken up. In

an op-ed

in May of 2019, Hughes said that since the last time he’d seen

Zuckerberg, in the summer of 2017, “Mark’s personal reputation and the

reputation of Facebook have taken a nose-dive,” and that while he hadn’t

worked there for a decade, “I feel a sense of anger and

responsibility.”

Buttigieg has

drawn considerable support from

Silicon Valley, with some in that engineer-soaked ecosystem seeing in

him a like-minded solutions-oriented and long-term thinker, an appealing

blend of technocrat and optimist who sees no problem that can’t be

carefully parsed. It doesn’t hurt that, at 38, Buttigieg is the

contemporary of many of the tech industry’s most prominent

leaders—sandwiched, for example, between the 35-year-old Zuckerberg and

43-year-old Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey. His national finance chair is a

prominent figure in Silicon Valley: Swati Mylavarapu, a venture

capitalist who, with her husband, Nest co-founder Matt Rogers, runs the

VC firm Incite. Netflix CEO Reed Hastings has hosted a fundraiser for

Buttigieg, and his high-profile donors include famed investor Ron

Conway, Y Combinator’s Sam Altman, and Lowercase Capital’s Chris Sacca.

Today,

Buttigieg is, says his campaign, closer both personally and

ideologically to Hughes than he is to Zuckerberg. “Pete and Chris speak

every few months,” Savett, the campaign spokesman, says. “Pete believes

Chris has made a really compelling case about the concentration of power

and that he’s made compelling arguments on a number of different

issues, including the future of tech.”

Buttigieg hasn’t called

for the company to be broken up; of the major Democratic candidates,

only Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders have gone that far—with others

in the field calling it distinctly Trump-like to dictate to federal

agencies, even hypothetically, specific companies to target. But

Buttigieg has grown harsher and harsher about the company as time goes

on.

Last February, Buttigieg, still a long-shot candidate, spoke

of Facebook and Zuckerberg as a problem fixable with a smart policy

tweak. Both, said Buttigieg, were “well-intentioned” but still reckoning

with the consequences of their roles in the world. “I think they

realized that there’s gotta be some kind of policy response, because

what they do is increasingly a matter of policy. I mean, in many ways

corporate policies of Google, Facebook, and the others are public

policy. And I think they take that seriously, I’m sure he does.”

But

some 11 months later, with Buttigieg rising dramatically in the

polls—and amid Facebook unveiling a series of controversial policy

decisions on how to approach the 2020 election—Buttigieg grew much

harsher. Just because he knew Zuckerberg, the candidate said, “doesn’t

mean we agree on a lot of things,” Buttigieg said in an interview with

the New York Times editorial board. Buttigieg had

once praised social media

for helping to introduce him to his husband, Chasten; Hinge, the dating

app they used to meet each other, at the time used Facebook’s network

of social connections. Now he was calling into question Facebook’s

entire ad-based business model.

Said Buttigieg of Zuckerberg, “no one should have that kind of power.”

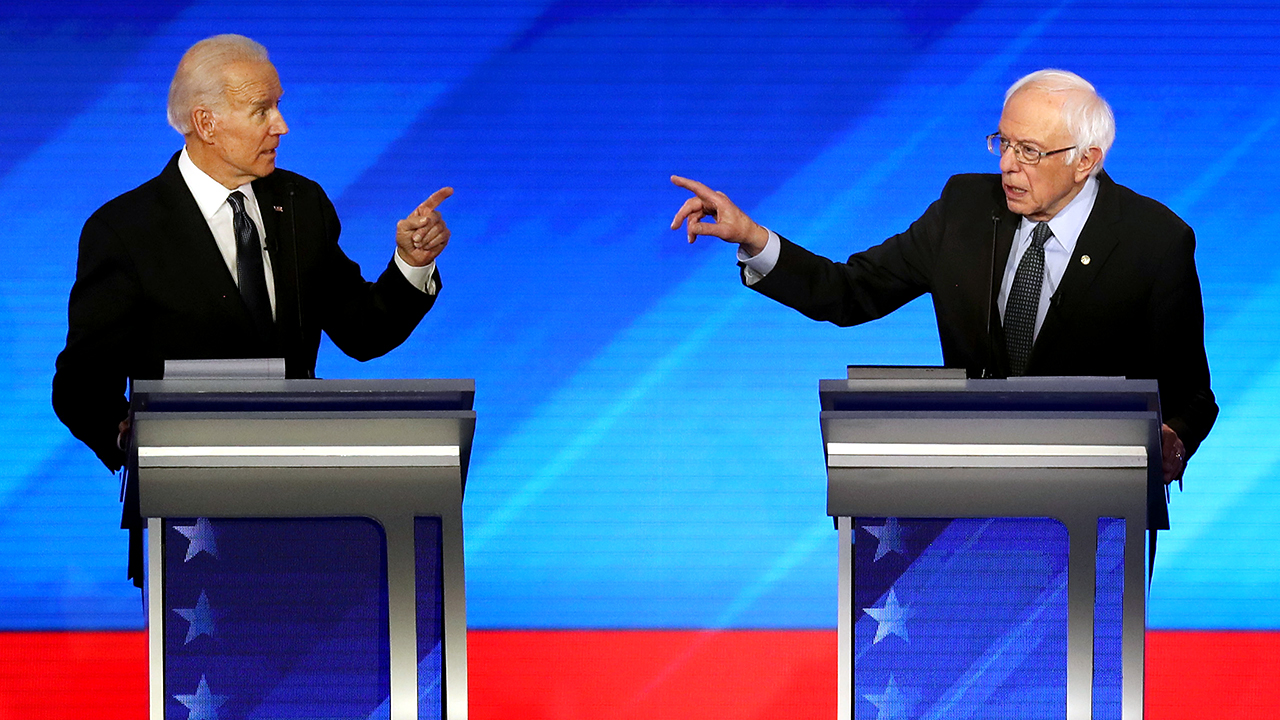

Joe

Biden and Bernie Sanders at the Feb. 7 Democratic presidential primary

debate at St. Anselm College in Manchester, New Hampshire. (Joe

Raedle/Getty Images)

Joe

Biden and Bernie Sanders at the Feb. 7 Democratic presidential primary

debate at St. Anselm College in Manchester, New Hampshire. (Joe

Raedle/Getty Images)