Most say ‘design and structure’ of government need big changes

At

a time of growing stress on democracy around the world, Americans

generally agree on democratic ideals and values that are important for

the United States. But for the most part, they see the country falling

well short in living up to these ideals, according to a new study of

opinion on the strengths and weaknesses of key aspects of American

democracy and the political system.

The public’s criticisms of

the political system run the gamut, from a failure to hold elected

officials accountable to a lack of transparency in government. And just a

third say the phrase “people agree on basic facts even if they disagree

politically” describes this country well today.

The perceived

shortcomings encompass some of the core elements of American democracy.

An overwhelming share of the public (84%) says it is very important that

“the rights and freedoms of all people are respected.” Yet just 47% say

this describes the country very or somewhat well; slightly more (53%)

say it does not.

Despite these criticisms, most Americans say

democracy is working well in the United States – though relatively few

say it is working very well. At the same time, there is broad support

for making sweeping changes to the political system: 61% say

“significant changes” are needed in the fundamental “design and

structure” of American government to make it work for current times.

The

public sends mixed signals about how the American political system

should be changed, and no proposals attract bipartisan support. Yet in

views of how many of the specific aspects of the political system are

working, both Republicans and Democrats express dissatisfaction.

To

be sure, there are some positives. A sizable majority of Americans

(74%) say the military leadership in the U.S. does not publicly support

one party over another, and nearly as many (73%) say the phrase “people

are free to peacefully protest” describes this country very or somewhat

well.

In general, however, there is a striking mismatch between

the public’s goals for American democracy and its views of whether they

are being fulfilled. On 23 specific measures assessing democracy, the

political system and elections in the United States – each widely

regarded by the public as very important – there are only eight on which

majorities say the country is doing even somewhat well.

The new

survey of the public’s views of democracy and the political system by

Pew Research Center was conducted online Jan. 29-Feb. 13 among 4,656

adults. It was supplemented by a survey conducted March 7-14 among 1,466

adults on landlines and cellphones.

Among the major findings:

Mixed

views of structural changes in the political system. The surveys

examine several possible changes to representative democracy in the

United States. Most Americans reject the idea of amending the

Constitution to give states with larger populations more seats in the

U.S. Senate, and there is little support for expanding the size of the

House of Representatives. As in the past, however, a majority (55%)

supports changing the way presidents are elected so that the candidate

who receives the most total votes nationwide – rather than a majority in

the Electoral College – wins the presidency.

A majority says

Trump lacks respect for democratic institutions. Fewer than half of

Americans (45%) say Donald Trump has a great deal or fair amount of

respect for the country’s democratic institutions and traditions, while

54% say he has not too much respect or no respect. These views are

deeply split along partisan and ideological lines. Most conservative

Republicans (55%) say Trump has a “great deal” of respect for democratic

institutions; most liberal Democrats (60%) say he has no respect “at

all” for these traditions and institutions.

Government

and politics seen as working better locally than nationally. Far more

Americans have a favorable opinion of their local government (67%) than

of the federal government (35%). In addition, there is substantial

satisfaction with the quality of candidates running for Congress and

local elections in recent elections. That stands in contrast with views

of the recent presidential candidates; just 41% say the quality of

presidential candidates in recent elections has been good.

Few

say tone of political debate is ‘respectful.’ Just a quarter of

Americans say “the tone of debate among political leaders is respectful”

is a statement that describes the country well. However, the public is

more divided in general views about tone and discourse: 55% say too many

people are “easily offended” over the language others use; 45% say

people need to be more careful in using language “to avoid offending”

others.

Americans

don’t spare themselves from criticism. In addressing the shortcomings

of the political system, Americans do not spare themselves from

criticism: Just 39% say “voters are knowledgeable about candidates and

issues” describes the country very or somewhat well. In addition, a 56%

majority say they have little or no confidence in the political wisdom

of the American people. However, that is less negative than in early

2016, when 64% had little or no confidence. Since the presidential

election, Republicans have become more confident in people’s political

wisdom.

Cynicism about money and politics. Most Americans think

that those who donate a lot of money to elected officials have more

political influence than others. An overwhelming majority (77%) supports

limits on the amount of money individuals and organizations can spend

on political campaigns and issues. And nearly two-thirds of Americans

(65%) say new laws could be effective in reducing the role of money in

politics.

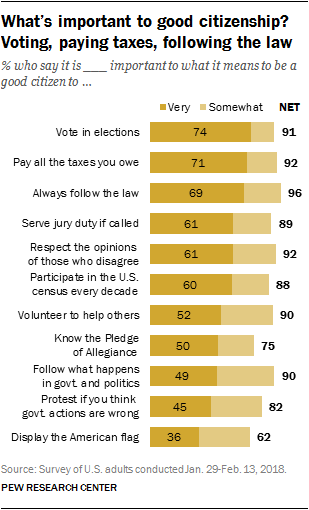

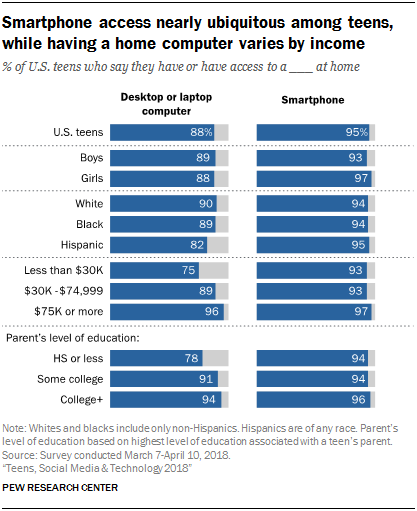

Varying

views of obligations of good citizenship. Large majorities say it is

very important to vote, pay taxes and always follow the law in order to

be a good citizen. Half of Americans say it is very important to know

the Pledge of Allegiance, while 45% say it is very important to protest

government actions a person believes is wrong. Just 36% say displaying

the American flag is very important to being a good citizen.

Most

are aware of basic facts about political system and democracy.

Overwhelming shares correctly identify the constitutional right

guaranteed by the First Amendment to the Constitution and know the role

of the Electoral College. A narrower majority knows how a tied vote is

broken in the Senate, while fewer than half know the number of votes

needed to break a Senate filibuster. (

Take the civics knowledge quiz.)

Democracy seen as working well, but most say ‘significant changes’ are needed

In

general terms, most Americans think U.S. democracy is working at least

somewhat well. Yet a 61% majority says “significant changes” are needed

in the fundamental “design and structure” of American government to make

it work in current times. When asked to compare the U.S. political

system with those of other developed nations, fewer than half rate it

“above average” or “best in the world.”

Overall, nearly

six-in-ten Americans (58%) say democracy in the United States is working

very or somewhat well, though just 18% say it is working very well.

Four-in-ten say it is working not too well or not at all well.

Republicans

have more positive views of the way democracy is working than do

Democrats: 72% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents say

democracy in the U.S. is working at least somewhat well, though only 30%

say it is working very well. Among Democrats and Democratic leaners,

48% say democracy works at least somewhat well, with just 7% saying it

is working very well.

More Democrats than Republicans say

significant changes are needed in the design and structure of

government. By more than two-to-one (68% to 31%), Democrats say

significant changes are needed. Republicans are evenly divided: 50% say

significant changes are needed in the structure of government, while 49%

say the current structure serves the country well and does not need

significant changes.

The public has mixed evaluations of the

nation’s political system compared with those of other developed

countries. About four-in-ten say the U.S. political system is the best

in the world (15%) or above average (26%); most say it is average (28%)

or below average (29%), when compared with other developed nations.

Several other national institutions and aspects of life in the U.S. –

including the military, standard of living and scientific achievements –

are more highly rated than the political system.

Republicans

are about twice as likely as Democrats to say the U.S. political system

is best in the world or above average (58% vs. 27%). As recently as four

years ago, there were no partisan differences in these opinions.

Bipartisan criticism of political system in a number of areas

Majorities

in both parties say “people are free to peacefully protest” describes

the U.S. well. And there is bipartisan sentiment that the military

leadership in the U.S. does not publicly favor one party over another.

In

most cases, however, partisans differ on how well the country lives up

to democratic ideals – or majorities in both parties say it is falling

short.

Some of the most pronounced partisan differences are in

views of equal opportunity in the U.S. and whether the rights and

freedoms of all people are respected.

Republicans are twice as

likely as Democrats to say “everyone has an equal opportunity to

succeed” describes the United States very or somewhat well (74% vs.

37%).

A majority of Republicans (60%) say the rights and

freedoms of all people are respected in the United States, compared with

just 38% of Democrats.

And while only about half of Republicans

(49%) say the country does well in respecting “the views of people who

are not in the majority on issues,” even fewer Democrats (34%) say this.

No more than about a third in either party say elected

officials who engage in misconduct face serious consequences or that

government “conducts its work openly and transparently.” Comparably

small shares in both parties (28% of Republicans, 25% of Democrats) say

the following sentence describes the country well: “People who give a

lot of money to elected officials do not have more political influence

than other people.”

Fewer than half in both parties also say

news organizations do not favor one political party, though Democrats

are more likely than Republicans to say this describes the country well

(38% vs. 18%). There also is skepticism in both parties about the

political independence of judges. Nearly half of Democrats (46%) and 38%

of Republicans say judges are not influenced by political parties.

Partisan gaps in opinions about many aspects of U.S. elections

For the most part, Democrats and Republicans agree about the importance of many principles regarding elections in the U.S.

Overwhelming

shares in both parties say it is very important that elections are free

from tampering (91% of Republicans, 88% of Democrats say this) and that

voters are knowledgeable about candidates and issues (78% in both

parties).

But there are some notable differences: Republicans

are almost 30 percentage points more likely than Democrats to say it is

very important that “no ineligible voters are permitted to vote” (83% of

Republicans vs. 55% of Democrats).

And while majorities in both

parties say high turnout in presidential elections is very important,

more Democrats (76%) than Republicans (64%) prioritize high voter

turnout.

The differences are even starker in evaluations of how

well the country is doing in fulfilling many of these objectives.

Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say that “no eligible

voters are prevented from voting” describes elections in the U.S. very

or somewhat well (80% vs. 56%). By contrast, more Democrats (76%) than

Republicans (42%) say “no ineligible voters are permitted to vote”

describes elections well.

Democrats – particularly politically

engaged Democrats – are critical of the process for determining

congressional districts. A majority of Republicans (63%) say the way

congressional voting districts are determined is fair and reasonable

compared with just 39% of Democrats; among Democrats who are highly

politically engaged, just 29% say the process is fair.

And fewer

Democrats than Republicans consider voter turnout for elections in the

U.S. – both presidential and local – to be “high.” Nearly three-quarters

of Republicans (73%) say “there is high voter turnout in presidential

elections” describes elections well, compared with only about half of

Democrats (52%).

Still, there are a few points of relative

partisan agreement: Majorities in both parties (62% of Republicans, 55%

of Democrats) say “elections are free from tampering.” And Republicans

and Democrats are about equally skeptical about whether voters are

knowledgeable about candidates and issues (40% of Republicans, 38% of

Democrats).

Democracy and government, the U.S. political system, elected officials and governmental institutions

Americans

are generally positive about the way democracy is working in the United

States. Yet a majority also says that the “fundamental design and

structure” of U.S. government is in need of “significant changes” to

make it work today.

Republicans are more likely than Democrats

to say U.S. democracy is working at least somewhat well, and less likely

to say government is in need of sweeping changes.

And far more

Republicans than Democrats say the U.S. political system is “best in the

world” or “above average” when compared with political systems of other

developed nations.

Overall, about six-in-ten Americans say

democracy is working well in the U.S. today (18% very well, 40% somewhat

well); four-in-ten say it is not working well (27% not too well and 13%

not at all well).

About seven-in-ten (72%) Republicans and

Republican-leaning independents say U.S. democracy is working very or

somewhat well, compared with 48% of Democrats and Democratic leaners.

Relatively small shares in both parties (30% of Republicans and just 7%

of Democrats) say democracy in the U.S. is working very well.

While

a majority of Americans say democracy in this country is working well,

about six-in-ten (61%) say significant changes to the fundamental design

and structure of government are needed to make it work for current

times; 38% say the design and structure of government serves the country

well and does not need significant changes.

By roughly

two-to-one (68% to 31%), Democrats say significant changes are needed,

while Republicans are divided (50% to 49%) over whether or not extensive

changes are needed.

Although the view that significant changes

are needed is widely held, those with higher levels of political

engagement are less likely to say this than people who are less

politically engaged.

Overall, those with high levels of

political engagement and participation are split over whether

significant changes are needed or not (51% vs. 48%). Views that the

American system of government needs far-reaching reforms are more

widespread among those with lower levels of engagement: 60% of those

with a moderate level of engagement say this, along with 71% of those

who are relatively unengaged with politics.

This pattern is

evident within both partisan coalitions: 40% of Republicans and

Republican leaners who are highly engaged with politics say the

fundamental design and structure of American government needs

significant reform, compared with 60% of low-engagement Republicans.

Similarly, while a 57% majority of highly engaged Democrats and

Democratic leaners say significant changes are needed, that share rises

to 78% of the least politically engaged Democrats.

Across

demographic groups, there are only modest differences in the shares

saying that democracy is working at least somewhat well, but there are

more pronounced differences on whether changes are needed to the

fundamental design and structure of government.

Whites (54%) are

less likely than blacks (70%) and Hispanics (76%) to say the government

needs significant change, but the three groups have similar assessments

of American democracy’s performance.

There also are significant

age gaps over whether extensive change is needed to the structure and

design of government, with 66% of adults younger than 50 saying this,

compared with 58% of those ages 50 to 64 and 50% of those 65 and older.

But age groups differ little in their evaluations of how well democracy

is functioning.

Educational groups also differ little in their

overall opinions of how well democracy is working. But those without a

bachelor’s degree (65%) are more likely to say the government needs

significant change than those with a college degree (54%) or a

postgraduate degree (45%).

Americans give their political system mixed grades

When

asked to compare the U.S. political system with others in developed

countries, only about four-in-ten Americans (41%) say it is “best in the

world” or “above average.” Most (57%) say it is “average” or “below

average.”

Several other national institutions and aspects of

life in the U.S. are more highly rated than the political system. Nearly

eight-in-ten (79%) say the U.S. military is either above average or the

best in the world compared with militaries in other developed nations –

with 38% calling it best in the world.

Larger shares also say

the U.S. standard of living, colleges and universities, scientific

achievements and economy are at least above average internationally than

say that about the political system. Only the nation’s health care

system (30% best in the world or above average) and public schools (18%)

are rated lower.

Republicans and Republican-leaning

independents generally give the U.S. better marks for its performance on

these issues than Democrats and Democratic leaners. About six-in-ten

Republicans say the country’s political system is above average or the

best in the world (58%), compared with about a quarter of Democrats

(27%). Republicans also give the country much higher marks than

Democrats on its standard of living, health care and economy.

The

shares of Republicans and Democrats giving the U.S. high marks on

several of these national institutions and aspects of American life have

diverged sharply since 2014.

Today, Republicans are about twice

as likely as Democrats to say the U.S. political system is above

average or the best in the world (58% vs. 27%).

In 2014, about

four-in-ten members of both parties gave the political system a positive

rating (37% of Republicans, 36% of Democrats); in 2009, identical

shares of Republicans and Democrats (52% each) said the U.S. political

system was at least above average.

Partisan divides are growing

in other areas as well. For example, 61% of Republicans and just 38% of

Democrats describe the U.S. economy as best in the world or above

average. Partisan differences in these assessments were much more modest

in 2014 and 2009.

Little public confidence in elected officials

Americans

express little confidence in elected officials to act in the best

interests of the public. Just a quarter say they have a great deal (3%)

or fair amount (22%) of confidence in elected officials.

That is

by far the lowest level of confidence in the six groups included in the

survey. Large majorities say they have a great deal or fair amount of

confidence in the military (80%) and scientists (79%). In addition,

higher shares express confidence in religious leaders (49%), business

leaders (44%) and the news media (40%).

Overall public

confidence in these groups is little changed since 2016, but in some

cases – including elected officials – the views among Republicans and

Democrats have shifted.

Though

majorities of both Republicans and Democrats continue to express little

or no confidence in public officials, Republicans (36%) are more likely

than Democrats (17%) to express at least a fair amount of confidence in

elected officials to act in the public interest. Two years ago, more

Democrats (32%) than Republicans (22%) had confidence in elected

officials.

The partisan gap in confidence in the news media also

has widened considerably. Today, 58% of Democrats and just 16% of

Republicans are confident in the news media to act in the public

interest. Since 2016, the share expressing at least a fair amount of

confidence in the news media has increased 12 percentage points among

Democrats, while falling 13 points among Republicans.

And more

Republicans have confidence in business leaders than did so two years

(62% now, 51% then). Far fewer Democrats express confidence in business

leaders (32%), and their views are little changed from two years ago.

Republicans

also express more confidence in the military (92%) than do Democrats

(73%), and the gap has not changed much since 2016.

State, local governments viewed more favorably than federal government

Americans

have more favorable opinions of their state and local governments than

the federal government in Washington. Two-thirds say they view their

local government favorably, and 58% have favorable views of their state

government. Only 35% of adults report a favorable opinion of the federal

government.

Views of federal, state and local government have

changed little over the past decade. Favorable opinions of the federal

government have fallen significantly since peaking in the wake of the

9/11 terrorist attacks.

While

overall views of the federal government in Washington are largely

unchanged from late 2015, Republicans and Democrats have moved in

opposite directions since then.

Today, 44% of Republicans and

Republican leaners have a favorable opinion of the federal government,

compared with 28% of Democrats and Democratic leaners. In 2015, views of

the federal government were reversed: 45% of Democrats had a favorable

view versus 18% of Republicans. Republicans’ and Democrats’ views of the

federal government also flipped between 2008 and 2009, when Barack

Obama won the presidency.

There are much smaller partisan

differences in favorability toward states and local government.

Majorities in both parties (61% of Republicans, 55% of Democrats) have

favorable impressions of their state government; similar shares in both

parties (69% of Republicans, 68% of Democrats) view their local

governments favorably.

Views of Congress and the Supreme Court

Views

of Congress remain extremely negative: Two-thirds of Americans say they

have an unfavorable view of Congress, compared with 30% saying their

view is favorable. The share expressing unfavorable views has increased

slightly from a year ago (62%).

With

their party in control of both houses of Congress, Republicans’ views

are slightly more favorable than Democrats: 37% of Republicans and

Republican leaners say this versus 24% of Democrats and Democratic

leaners. Republican’s attitudes are more negative than a year ago, when

44% had a favorable opinion. Views among Democrats are mostly unchanged.

Attitudes toward the Supreme Court continue to improve

after reaching 30-year lows in 2015. Republicans’ views, in particular, are now more positive than three years ago.

Two-thirds

of the public says they view the court favorably, and about

three-in-ten (28%) hold unfavorable views. The share of the public

saying it has a favorable view of the Supreme Court has increased 18

percentage points since 2015 (48%).

Most

Republicans viewed the Supreme Court unfavorably after its decisions on

the Affordable Care Act and same-sex marriage in summer 2015: Just a

third of Republicans viewed the court favorably, compared with about

six-in-ten Democrats (61%). Today, more Republicans (71%) hold a

favorable view of the Supreme Court than Democrats (62%). Favorable

views among Democrats have fallen since 2016.

Views of American democratic values and principles

The

public places great importance on a broad range of democratic ideals

and principles in the United States today. Across 16 democratic values

asked about in the survey – including respecting the rights of all,

having a balance of power across government branches and having

officials face serious consequences for misconduct – large majorities

say these are very important for the country.

But evaluations of

how well the country is upholding these values are decidedly mixed. And

when it comes to ideals more squarely in the political arena, such as

an unbiased news media, partisan cooperation and respectful political

debate, broad majorities of the public – including large shares of both

Republicans and Democrats – say the country is falling short.

Nine-in-ten

or more say each of the 16 items is at least somewhat important for the

country. About eight-in-ten or more say it is very important for the

country that the rights and freedoms of all are respected (84%),

officials face serious consequences for misconduct (83%), that judges

are not influenced by political parties (82%), and that everyone has an

equal opportunity to succeed (82%).

Majorities place great

importance on partisan cooperation (78% very important), independent

news media (76%) and the right to peaceful protest (74%).

Comparably

large shares also say it is very important that the government is open

and transparent (74%) and that people who give a lot of money to elected

officials do not have more political influence than other people (74%).

The public is relatively less likely to emphasize the

importance of respecting the views of those who are not in the majority,

respectful tone in political discourse, shared acceptance of basic

facts, and government policies that reflect the views of most Americans.

Still, roughly 90% call these principles at least somewhat important,

including about six-in-ten who say each is very important.

About

three-quarters say the U.S. is described very or somewhat well by the

phrases “military leadership does not publicly express support for one

party over the other” (74%) and “people are free to peacefully protest”

(73%).

More than half (55%) say the executive, legislative and

judicial branches of government keep the others from having too much

power; and 52% think the country is described well by the phrase

“everyone has an equal opportunity to succeed.

However, for the

remaining 12 of 16 democratic ideals and principles included in the

survey, majorities say they describe the country as doing not too or not

at all well.

For instance, on such core principles as an

independent judiciary, just 43% say that “judges are not influenced by

political parties” describes the country well; 56% say this describes

the country not too or not at all well.

Larger majorities say

that an open and transparent government (69%) and news organizations

that do not favor a political party (70%) do not describe the country

well.

Some of the public’s most negative judgements are reserved

for values that are most squarely in the political sphere. Large

majorities do not see partisan cooperation (80%) or respectful political

debate (74%) as describing the country well. Similarly, 72% say the

country is not well described as a place where people who contribute to

campaigns do not have more influence than other people; 69% also say the

phrase “elected officials face serious consequences for misconduct”

does not describe the country well.

In

general, there are wide gaps between the importance the public places

on a value and public perception of how well the country reflects that

value.

Nearly eight-in-ten (78%) say it is very important for

Republicans and Democrats to work together on issues, but the public is

59 percentage points less likely to say partisan cooperation describes

the country very or fairly well (19%). Such wide gaps characterize a

range of issues across dimensions.

For instance, 84% say it is

very important for the country that the rights and freedoms of all

people are respected, but far fewer (47%) say this describes the country

well. And few (34%) think that people in the country agree on basic

facts, even though most (60%) think this is very important.

There

are a few exceptions to this pattern. There is no gap in the shares who

say the right to peaceful protest is very important (74%) and say it

describes the country well (73%). And nonpartisan military leadership is

the only democratic ideal for which more say this describes the country

very or somewhat well (74%) than say it is very important (66%).

Partisan differences in views of democratic values

On

the whole, Republicans and Democrats largely agree on the importance of

many democratic values. A majority within each partisan coalition says

that each of the 16 items included in the survey is very important to

the country.

For instance, comparably large shares of

Republicans and Republican-leaning independents (84%) and Democrats and

Democratic leaners (83%) say it is very important that judges are not

influenced by political parties. Similarly, 77% of Democrats and 75% of

Republicans say it is very important for there to be a balance of power

across branches of government.

However, there are a handful of

significant differences between the views of partisans. One of the

largest is over the importance of the right to protest. About

eight-in-ten Democrats and Democratic leaners (82%) say it’s very

important that people are free to peacefully protest, compared with a

smaller 64% majority of Republicans and Republican leaners (another 29%

of Republicans say this is somewhat important).

Democrats

also are somewhat more likely than Republicans to say it is very

important that the views of those who are not in the majority on issues

are respected (66% vs. 56%).

By contrast, Republicans are more

likely than Democrats to say it is very important that news

organizations do not favor one political party (77% vs. 66%).

Sizable partisan gaps on whether all have an equal opportunity for success, people’s rights are respected

There

are bigger gaps between the views of Republicans and Democrats when it

comes to how well the country is doing in living up to many democratic

ideals and principles.

Most Republicans and Republican leaners

say the phrases “everyone has an equal opportunity to succeed” (74%) and

“the rights and freedoms of all people are respected” (60%) describe

the country well.

Democrats and Democratic leaners disagree:

Just 37% think the country merits being described as a place with equal

opportunity, and only 38% say the country is described well as a place

where the right and freedoms of all are respected.

Larger

majorities of Republicans than Democrats also say the country is

described well as a place where military leadership does not publicly

express partisan preferences (83% vs. 69%) and where people are free to

peacefully protest (80% vs. 68%). About half of Republicans (49%) think

the description of the U.S. as a place where the views of those not in

the majority are respected applies; about a third of Democrats (34%) say

the same.

Democrats are more positive than Republicans when it

comes to questions about bias and independence among news organizations.

Overall, 53% of Democrats say “news organizations are independent of

government influence” describes the country well. Far fewer Republicans

(31%) say the same. And while relatively small shares of both parties

say the country is described well as having news organizations that

don’t favor one political party, Democrats (38%) are more likely to say

this than Republicans (18%)

However, there are a number of

values on which there is little difference in the views of Republicans

and Democrats. In particular, similar shares of those in both parties

say descriptions of partisan cooperation, respectful political debate,

basic agreement on facts, limits on the political influence of money and

serious consequences for official misconduct do not describe the

country well.

Political engagement, partisanship and assessments of democratic values

In

several areas, especially on items related to news organizations,

partisan differences are even larger among those who are highly engaged

politically.

When it comes to whether news organizations in the

country are independent of government influence, 60% of highly engaged

Democrats say this describes the country very or fairly well, compared

with just 27% of highly engaged Republicans – an opinion gap of 33

percentage points. Divides in views are more modest between Republicans

and Democrats with medium (14 points) or low (16 points) levels of

political engagement.

There also is a substantial partisan

divide among those with high or medium levels of political engagement

over whether government policies in the country today reflect the views

of most Americans and whether the views of those not in the majority are

respected. However, among Republicans and Democrats with low levels of

political engagement, there are very modest differences in views.

Similar

patterns are seen in views of equal opportunity and whether the rights

and freedoms of all are respected. More politically engaged Democrats

are less likely than less engaged Democrats to say these descriptions

apply to the U.S.

Age and views of democratic ideals and principles

There

is general agreement across age groups about the importance of key

democratic values. Large majorities of both old and young say each of

the 16 items included in the survey is very or somewhat important for

the U.S. However, on many items, there are differences in the shares

describing a number of values as “very important,” with older adults

more likely to place higher levels of importance on an item than younger

adults.

For

example, while large majorities of 90% or more say transparent

governance is important, those 65 and older are more than 20 percentage

points more likely than those under 30 to call this very important (84%

vs. 63%). In views of people agreeing on “basic facts” even if they

disagree on politics, sizable majorities across age categories regard

this as important, but 70% of those 65 and older say it is very

important, compared with no more than about six-in-ten in younger age

groups.

However, there are exceptions to this general pattern.

There are no significant differences in views of the importance of

people having the right to protest peacefully – about three-quarters in

each category regard this as very important.

There are modest

age differences in evaluations of how well the country is doing in

living up to these democratic values. On the right to peacefully

protest, for example, about eight-in-ten of those 50 and older (79%) say

it describes the U.S. well, compared with a smaller majority (68%) of

those under 50.

Elections in the U.S.: Priorities and performance

As

is the case with overall views of the political system, the public sees

a range of objectives as important for U.S. elections. However,

assessments of how well these goals are being achieved vary widely – and

many evaluations are deeply divided along partisan lines.

Overwhelming

majorities of Americans – including most Republicans and Democrats –

say it is very important that elections are free from tampering (90% say

this) and that no eligible voters are prevented from voting (83%).

Large

majorities also say it is very important that voters are knowledgeable

about candidates and issues (78%), the way congressional districts are

determined is fair and reasonable (72%) and there is high voter turnout

in presidential elections (70%).

And two-thirds (67%) say it is

very important that no ineligible voters are permitted to vote, while

62% prioritize high turnout in local elections.

Nearly all

Americans say each of these items is very or somewhat important. Very

few – no more than about 10% in any case – say they are not too

important or not at all important.

Yet

the public has mixed views on whether these goals are being fulfilled.

Majorities say several describe elections in the United States very or

somewhat well, but relatively few say they describe elections very well.

Roughly two-thirds think the statement “no eligible voters are

prevented from voting” describes elections in the U.S. very (29%) or

somewhat (36%) well; about a third say this describes U.S. elections not

too well (21%) or not at all well (12%).

Similarly, about

six-in-ten (61%) say “no ineligible voters are permitted to vote”

describes elections very (29%) or somewhat (32%) well; 37% say this does

not describe U.S. elections well.

Most also say there is high

voter turnout in presidential elections (24% say this describes

elections very well, 36% somewhat well), and that elections in the U.S.

are free from tampering (19% very well, 39% somewhat well).

Opinions

are more divided about whether congressional districts are fairly

determined: 49% say fairly drawn congressional districts describes U.S.

elections very or somewhat well; just as many (49%) say this describes

U.S. elections not too or not at all well (49%).

And fewer than

half say “there is high voter turnout in local elections” (41%) and

“voters are knowledgeable about candidates and issues” (39%) describe

elections well.

The

mismatch between the public’s priorities for elections and its view of

reality is most apparent in views of voters being knowledgeable. About

three-quarters (78%) rate this as very important, but only half as many

(39%) say this describes elections very or somewhat well.

And

while 90% say it is very important that elections are free from

tampering, a much smaller majority (57%) says this describes elections

well – with just 19% saying it describes elections very well.

Partisans share goals for elections, with a few exceptions

Republicans

and Democrats widely agree on the most important electoral components

for the U.S. Nearly nine-in-ten across both parties say it is very

important that elections are free from tampering: 91% of Republicans and

Republican-leaning independents say this, as do 88% of Democrats and

Democratic leaners.

Comparable majorities in both parties also

say it’s very important that no eligible voters are prevented from

voting (85% of Republicans, 83% of Democrats).

Partisans are

deeply divided, however, over the importance of preventing ineligible

voters from casting ballots. More than eight-in-ten Republicans (83%)

cite this as very important, compared with 55% of Democrats (27% of

Democrats say this is somewhat important).

More Democrats (76%)

than Republicans (64%) view high turnout in presidential elections as

very important, and Democrats are also more likely to prioritize having a

fair process for determining congressional districts (76% of Democrats,

68% of Republicans).

While

there is broad agreement over the important aspects of U.S. elections,

there are deep divisions when it comes to how they are actually being

conducted today.

In particular, Republicans and Democrats have

vastly different assessments of U.S. elections when it comes to

perceptions of whether ineligible voters are permitted to vote, and

whether eligible voters are prevented from voting.

A large

majority of Republicans (80%) say “no eligible voters are prevented from

voting” describes U.S. elections very or somewhat well. A much narrower

majority of Democrats (56%) agree.

By contrast, when it comes

to not allowing any ineligible voters to vote, Democrats are far more

likely than Republicans to think the U.S. is doing at least somewhat

well. Roughly three-quarters of Democrats and Democratic leaners say

this (76%), compared with just 42% of Republicans and Republican

leaners.

The divide in views of whether congressional districts

are drawn fairly is nearly as wide. A 63% majority of Republicans say

fair and reasonable determination of voting districts describes the U.S.

at least somewhat well. By contrast, a majority of Democrats (58%) say

this does not describe the U.S. well; 39% say it does.

And while

nearly three-quarters of Republicans (73%) say “there is high voter

turnout in presidential elections” describes elections well, only about

half of Democrats (52%) view turnout as “high.” More Republicans also

say turnout in local elections is high (48% vs. 36%).

Politically engaged Democrats highly critical of process for determining congressional districts

Politically

engaged Democrats attach a great deal of importance to the issue of

fairly drawn congressional districts. And they are decidedly skeptical

about whether this goal is being achieved.

Nearly nine-in-ten

Democrats who are highly politically engaged (87%) say it is very

important that the way congressional districts are determined is fair

and reasonable. Smaller shares of less engaged Democrats – and

Republicans of differing levels of political engagement – say this is

very important.

And just 29% of the most politically engaged

Democrats give positive evaluations of whether districts are being

determined fairly and reasonably. Larger shares of less politically

engaged Democrats – including 51% of the least engaged – say this

describes U.S. elections well. Among Republicans, majorities across all

levels of political engagement say districts are being fairly

determined.

In

considering whether no ineligible voters are permitted to vote,

Republicans and Republican leaners with high levels of engagement are

most skeptical: Just about a third (34%) say the U.S. is doing at least

somewhat well. By contrast, Republicans with low levels of political

engagement are much more positive: A slim majority (54%) thinks this

describes the U.S. at least somewhat well.

Among Democrats, the

highly engaged overwhelmingly think the U.S. does at least somewhat well

in this area (85%), and the partisan gap stands at 51 percentage

points. A smaller majority of low-engagement Democrats (68%) think this

describes the U.S. well; the gap among those with low levels of

engagement is just 15 points.

Similarly, the partisan gap is

wider among the highly engaged in views of whether eligible voters are

prevented from voting. While Republicans across the board think the U.S.

does well when it comes to ensuring eligible voters are not prevented

from voting, highly engaged Democrats are somewhat less likely than

those with lower levels of engagement to think this.

Democracy, the presidency and views of the parties

The

American public has doubts about Donald Trump’s level of respect for

the country’s democratic institutions and traditions. Like all views of

Trump, attitudes are deeply partisan; Republicans give the president

positive marks in this regard, while Democrats are highly negative.

Overall,

54% say Trump has not too much (25%) or no respect at all (29%) for the

nation’s democratic institutions and traditions; somewhat fewer (45%)

say he has a great deal (23%) or a fair amount (22%) of respect for

them. The share saying Trump has at least a fair amount of respect for

the country’s democratic institutions is slightly higher than it was in

February 2017, when just 40% took this view.

Republicans and

Republican-leaning independents are confident in Trump’s respect for the

country’s democratic institutions and traditions: About three-quarters

(77%) say he has at least a fair amount of respect for them, including

45% who say he has a great deal of respect. There is a divide among

Republicans on this question by ideology. Conservative Republicans (84%)

are much more likely than moderates and liberals (64%) to say Trump

respects the country’s democratic institutions; and conservative

Republicans are about twice as likely as moderate and liberal

Republicans to say Trump has a great deal of respect for the country’s

democratic system (55% vs. 27%).

Democrats and Democratic

leaners are highly critical of Trump’s regard for the nation’s

democratic system. Just 16% think he has at least a fair amount of

respect for the country’s democratic institutions and traditions; 51%

say he has none at all, and another 32% say he has not too much. There

also are ideological differences among Democrats on this question;

liberals (60%) are more likely than moderates and conservatives (43%) to

say Trump has no respect at all for the country’s democratic

institutions and traditions.

Public sees risks in granting greater presidential powers

A

large majority of Americans say it’s important for there to be a

balance of power between the three branches of the federal government.

Consistent with this view, most oppose the idea of strengthening the

power of the executive branch. Just 21% say that many of the country’s

problems could be dealt with more effectively if the president didn’t

have to worry so much about Congress or the courts. About three-quarters

(76%) say that it would be too risky to give U.S. presidents more power

to deal directly with the country’s problems.

Public opposition

to strengthening the powers of the presidency has held steady over the

past few years. In two previous surveys – conducted in August 2016,

during Barack Obama’s final year in office, and in February 2017 –

similar shares of the public said it would be too risky to give U.S.

presidents more power.

Most

Republicans and Democrats oppose expanding the powers of the

presidency. However, in the current survey, opposition to this is

somewhat higher among Democrats and Democratic leaners (83%) than among

Republicans and Republicans leaners (70%). By contrast, in August 2016,

when Obama was president, a greater share of Republicans (82%) than

Democrats (66%) opposed granting the president expanded powers at the

expense of Congress and the courts.

On the whole, younger adults are more cautious about expanding executive power than older adults.

Among

those ages 18 to 29, 85% say it’s too risky to give presidents more

power. By comparison, a smaller majority of those 65 and older say the

same (62%).

This age dynamic exists within both parties. While

partisans across age cohorts say it would be too risky to give

presidents more power to deal directly with the country’s problems,

Democrats and Republicans younger than 50 are more likely than their

older counterparts to hold this view.

Most say the president has large impact on U.S. standing, national mood

Most

Americans say the president has a big impact in areas such as national

security and U.S. standing in the world, but relatively few say the

occupant of the executive office makes a big difference in their

personal lives.

Overall, 69% say that who is president makes a

big difference on the standing of the U.S. in the world; most also say

the president makes a big difference for the mood of the country (63%)

and national security (61%). About half (53%) say that who is president

makes a big difference for the economy.

By contrast, far fewer

(34%) think who is president makes a big difference in their own

personal lives; 39% say it makes some difference and a quarter say it

makes no difference.

Women

are more likely than men to say who is president makes a big difference

in their own personal lives. Four-in-ten women say this compared with

about three-in-ten men (29%).

Young adults ages 18 to 29 are

less likely than older adults to say that who is president makes a big

difference for their own personal life. Just 24% of those 18 to 29 say

this, compared with 34% of those ages 30 to 49, 37% of those 50 to 64

and 44% of those 65 and older.

Favorability ratings of the Republican and Democratic parties

On

balance, the public offers negative ratings of both the Republican and

Democratic parties. By 55%-41% more take an unfavorable than favorable

view of the Republican Party. Views of the Democratic Party are similar:

54% have an unfavorable view, compared with 42% who rate the party

favorably.

Ratings of the Republican Party are now higher than

they were for much of 2015 and 2016, prior to the election of Donald

Trump. However, they are down from a recent high of 47% in January 2017,

immediately after the election.

By contrast, views of the

Democratic Party are about as low or lower than they were at any point

during the run-up to the 2016 election. Favorable ratings of the

Democratic Party reached 52% in October 2016 and were about that high in

January 2017, before declining in the spring of that year.

Declining

views of the Democratic Party are tied, in part, to more negative

ratings among those who lean toward the Democratic Party but do not

identify with it.

Overall, 53% of Democratic leaners hold a

favorable view of the party, down from 73% who said this in January

2017. The current ratings of the party among Democratic leaners are as

low as they have been at any point in Pew Research Center surveys

conducted over the past two decades.

By contrast, about

two-thirds (65%) of Republican leaners view the GOP favorably. These

ratings are down somewhat from a post-election high, but remain far more

positive than at most other points over the past several years.

There

is no difference between how self-identifying Republicans and Democrats

rate their own parties. Overall, 82% of Republicans and the same share

of Democrats say they view their respective party favorably.

For

the past several decades, members of both parties have expressed

predominantly unfavorable views of the opposing party. But the intensity

of these attitudes is much higher today than it was 10 or 20 years ago.

Overall, comparable majorities of Democrats and Democratic

leaners (86%) and Republicans and Republican leaners (84%) say they hold

unfavorable views of the opposing party. Among Republicans, 45% say

they hold a very unfavorable view of the Democratic Party; a similar

share of Democrats (43%) has a very unfavorable view of the GOP. In

1994, just 17% of Republicans and 16% of Democrats said they viewed the

opposite party very unfavorably; and as recently as 2009, only about a

third of both groups held intensely negative views of the other

political party.

Recent Pew Research Center surveys have found that

antipathy toward the other party is a key driver of an individual’s own party identification.

Majorities of Republicans and Democrats – as well as Republican and

Democratic leaners – cite harm from the opposing party’s policies as a

major reason for their own partisan orientation.

With

the public holding relatively dim views of both major political

parties, almost a quarter (24%) now have unfavorable views of both the

Republican and Democratic parties.

The share with unfavorable

views of both parties was just 6% back in 1994; it is now as high as it

has ever been in Pew Research Center surveys dating to that year.

Just 11% of the public say they have a favorable view of both major parties – down from 32% in 1994.

Most

Americans (60%) continue to view one party favorably and the other

unfavorably. The share with this combination of views has stayed

relatively steady over the past few decades as unfavorable views toward

both parties have increased and favorable views of both parties have

decreased.

Most of those with unfavorable views of both parties

identify as independents (63%); Democratic-leaning independents make up a

slightly larger share than Republican-leaning independents. A plurality

(41%) describe themselves as moderate; 28% are conservative and 28% say

they are liberal. Those who have an unfavorable opinion of both major

parties also tend to be relatively young (59% are under age 50).

The Electoral College, Congress and representation

A

majority (55%) of Americans say the Constitution should be amended so

that the candidate who wins the most votes in the presidential election

would win, while 41% say the current system should be kept so that the

candidate who wins the most Electoral College votes wins the election.

These

views are little changed since a CNN/ORC survey conducted in the weeks

following the 2016 presidential election in which Donald Trump won the

Electoral College but lost the popular vote. But the public expresses

somewhat less support for moving to a popular vote than it did in 2011

(62%).

The movement in overall opinion since 2011 has been

driven by changes among Republicans and Republican-leaning independents.

Seven years ago Republicans were more divided in their views (43% keep

current system, 54% change to popular vote). But in the wake of the 2016

election, the share of Republicans supporting a constitutional

amendment to move to a popular vote dropped to just 27%. Today, 32% of

Republicans say the Electoral College should be eliminated, while 65%

say the current system should be maintained.

Three-quarters of

Democrats and Democratic leaners (75%) say the Constitution should be

amended so the candidate with the most overall votes wins, little

different than in prior surveys conducted over the past 18 years (the

question was first asked shortly after the 2000 election, in which

George W. Bush became president after winning a majority of votes in the

Electoral College; Al Gore narrowly won the popular vote).

Public

support for shifting to the popular vote to determine the winner of

presidential elections is higher in states that are less politically

competitive under the current system. About six-in-ten of those in both

“red” (57%) and “blue” (60%) states (those that solidly vote either

Republican or Democratic, respectively) support moving to a popular

vote. By contrast, only about half (48%) of those living in battleground

states say this.

In particular, Republicans in battleground

states are significantly more likely than other Republicans to say the

system should stay as it is: 75% of Republicans who live in battleground

states say this, compared with about six-in-ten Republicans who reside

in either red (58%) or blue (63%) states. Attitudes of Democrats in

battleground states are no different from those of Democrats in less

competitive states.

Should the allocation of Senate seats or the size of the House be changed?

Most

Americans reject the idea of changing the way Senate seats are

allocated. Public attitudes about this question of representation are

only modestly different when respondents are presented with information

about how the gap in population between the largest and smallest states

has changed since the early days of the republic.

Overall, 75%

say the current system of equal representation of states should be

maintained and 24% say the Constitution should be amended to give states

with larger populations more representation in the Senate.

When

the question includes additional information about how relative

population sizes have shifted over time (the wording: “When the first

Congress met, the state with the largest population had about 10 times

as many people as the state with the smallest population. Currently, the

state with the largest population has about 66 times as many people as

the state with the smallest population.”), opinion shifts modestly in

the direction of support for changing the allocation of Senate seats.

Still, just 29% of Americans say they favor changing Senate seat

apportionment when the question includes this information, while about

two-thirds (68%) say it should not be changed.

Majorities

across all partisan and ideological groups say all states should

continue to have two U.S. senators, regardless of population size (and

in both versions of the question). But there is a partisan gap in these

views.

When the question asks about the current structure of the

Senate without additional information, 85% of Republicans and

Republican leaners and 68% of Democrats and Democratic leaners say the

current system of equal representation of states should be maintained.

About one-in-three Democrats (31%) and just 14% of Republicans think the

Constitution should be amended so states with larger populations have

more senators than smaller states.

Republicans’ views are no

different between the versions of the question with and without

additional historical information about the population distribution.

Among Democrats, however, there is somewhat more support for amending

the Constitution to change senatorial apportionment when the changing

population distribution is made salient, though this remains a minority

position among Democrats (39% support these changes in that case,

compared with 31% in the version of the question without that

information).

Senate allocation and House size survey experiments

When

asked about the number of representatives in the U.S. House relative to

the number of people they represent, about half of Americans (51%) say

the lower chamber’s size should remain unchanged, while 28% say it

should be increased and 18% say it should be decreased.

The

public’s views shift modestly in the direction of increasing the size of

the House in a version of the question that provides additional

historical context. When the question notes that there were both fewer

members of the House when the first Congress met than there are today

(65 then, 435 now) and that each representative then represented a

smaller number of constituents (roughly 60,000 then, 700,000 now), 34%

say its size should be increased (compared with 28% without the

historical sizes). Still, a plurality (44%) say the size should remain

the same even with this additional information. The share saying the

size of Congress should be decreased also remains about the same (21%).

In

the version of the question without additional historical context, 55%

of Republicans and Republican leaners say the size of the U.S. House

should remain the same, while the remainder are about evenly divided:

21% say the number of members should be increased and 22% say decreased.

The view that the size should not change also is held by about half of

Democrats and Democratic leaners (49%). But Democrats who think the

House’s size should change are far more likely to say it should be

increased than decreased (34% vs. 14%).

Republicans’ views are

no different with the addition of information about the historical size

of the House. However, the balance of Democratic opinion shifts somewhat

when this information is provided. In this case, 44% of Democrats say

the House’s size should be increased (up from 34% without the additional

context), while a smaller share say the size should stay the same (39%,

down from 49% without the additional context). There is no difference

in the share of Democrats across the two conditions who say the House’s

size should be decreased.

Quality and responsiveness of elected officials

In

general, Americans have low regard for elected officials. And when

asked about candidates running for office in the last several elections,

only about half (47%) say the quality of candidates overall has been

good, with just 7% saying they have been “very good”; about as many

(52%) take a negative view.

Yet the public makes clear

distinctions in evaluations of candidate quality, depending on whether

they are running for president, Congress or a local office.

Ratings

of the field of presidential candidates in recent elections are similar

to ratings of generic candidates for political office: 41% rate the

quality of recent presidential candidates at least somewhat good (just

3% say very good), while 58% say they have generally been bad.

But

the public offers more positive views of those running for offices

closer to home: 64% say the quality of candidates running for Congress

in the last several elections in their district has generally been at

least somewhat good, while nearly three-quarters (73%) rate candidate

quality in local elections (such as for mayor or county government)

positively.

Across

different types of elections, about six-in-ten Americans say that they

“usually feel like there is at least one candidate who shares most of my

views.”

When asked generally about candidates for political

office, 63% of Americans say there is usually at least one candidate who

shares their views. That figure does not vary much when they are asked

about specific offices: 65% say at least one presidential candidate

usually represents most of their views, and 63% say the same about

congressional candidates and 62% about candidates for local political

office.

Overall,

Republicans and Republican-leaning independents are more likely than

Democrats and Democratic leaners to say the quality of candidates

running for president has been good in recent years (49% vs. 35%).

Conversely, Democrats are more likely than Republicans to rate their

recent slates of local candidates positively (77% vs. 69%). Partisans

view their recent congressional candidates similarly (67% of Republicans

and Republican leaners say they have been good, compared with 63% of

Democrats and Democratic leaners).

Within both partisan

coalitions, however, those who identify with the party are significantly

more likely than those who do not (and instead “lean” to the party) to

view the quality of recent candidates positively. This pattern is

evident across presidential, congressional and local contests.

For

example, while 77% of those who identify as Republicans say that the

quality of candidates running for Congress in their district has been at

least somewhat good in recent elections, just 53% of those who lean

toward the Republican Party say the same. There is a similar gap between

Democrats (74%) and Democratic leaners (48%).

Partisan

identifiers also are more likely than independents to say that in these

types of elections they usually feel that at least one candidate

represents their views. Asked about candidates for political office

generally, about seven-in-ten Republicans (71%) and Democrats (73%) say

this; by comparison, 61% of Republican-leaning independents and 49% of

Democratic-leaning independents say the same.

Evaluations of the

congressional candidate field vary based on the degree to which

partisans “fit” the partisan cast of their district. For instance, among

Republicans and Republican leaners who live in districts that have

voted for Republican congressional candidates by wide margins in recent

elections, about eight-in-ten (78%) say the quality of candidates in

their district is good. Among those who live in more politically mixed

(“swing”) districts, 73% say this, as do just 50% of Republicans who

live in overwhelmingly Democratic districts.

Among

Democrats there is a similar, if less dramatic, pattern. About

seven-in-ten (71%) living in heavily Democratic districts say the

quality of candidates running in their districts is good, compared with

64% of Democrats who live in swing districts and 53% who live in

predominantly Republican districts.

Nearly identical patterns

are evident in reports of whether or not people think at least one

candidate in congressional elections in their district shares their

values.

Expectations about the responsiveness of elected officials

About

six-in-ten Americans say that if they contacted their member of the

U.S. House of Representatives with a problem it is either not very

likely (40%) or not likely at all (21%) they would get help addressing

it. Just 7% say their representative would be very likely to help, while

30% say this would be somewhat likely.

Overall, Republicans are

somewhat more likely than Democrats to say that their congressional

representative would be at least somewhat likely to help them address an

issue (41% of Republicans vs. 35% of Democrats).

But these

perceptions vary across districts. In both parties, those who live in

districts represented by a member of their same party are more likely to

anticipate that their member of Congress would help them with a

problem. For instance, while 35% of Republicans living in districts

represented by Democrats say they would expect assistance, that rises to

45% among Republicans living in districts with a GOP representative.

Similarly, Democrats who live in districts represented by a Democrat are

more likely than Democrats in districts represented by Republicans to

say their congressional representative would respond if contacted (40%

to 31%, respectively).

Overall, adults who are politically

engaged are more likely than those who are less engaged to expect that

their representative would address an issue if contacted. This pattern

holds true controlling for both partisanship and the partisanship of the

district’s representative.

What should happen when the majority and a governor’s supporters don’t agree?

Three-quarters

of Americans (75%) say that when a new bill is supported by a majority

of people in a state – but opposed by the governor’s supporters – the

governor should follow the will of the majority and sign the

legislation. And while there are no differences between Republicans and

Democrats in these views when the governor’s party is not specified,

partisans’ answers do differ when the partisanship of the governor (and

the governor’s supporters) is mentioned.

Using a survey

experiment in which subsets of the public were presented with and

without partisan descriptions of the governor and the governor’s

supporters, wide majorities in every condition of the experiment support

the governor signing a bill that most of the people in the state

support even though the governor’s own supporters (or co-partisans)

oppose the bill. (See box below for full details of the experiment.)

Majorities

of both Republicans and Democrats say – in this hypothetical – that the

governor should sign the bill, regardless of the partisanship assigned

to the governor and the governor’s supporters. However, partisan support

for going along with the majority view is substantially lower when the

example provided results in their own party’s position being given less

priority.

For example, when given no party reference, 75% of

Republicans and Republican-leaning independents say the governor should

follow the will of the majority, but when told that the governor is also

a Republican and that Republicans oppose the bill, a narrower majority

(66%) of Republicans say that the governor should sign the bill.

A

nearly identical pattern is seen among Democrats and Democratic-leaning

independents: 77% support signing in the generic case, compared with

68% when the governor and supporters are identified as Democrats.

But

partisans differ in their response to the example of a governor of the

opposing party. Presented with an example of a bill on the desk of a

Republican governor that is opposed by Republicans but supported by the

majority of the state, the same share of Democrats say the governor

should follow the will of the majority as say this when not provided any

cues about the party of the governor or the governor’s supporters (77%

in both cases).

By contrast, when Republicans are presented with

a hypothetical Democratic governor, with Democrats opposed to the bill,

they are substantially more likely to say that the governor should

follow the will of the majority of the state rather than the governor’s

supporters (90% say this) than they do in either the generic condition

(75%) or when the governor and governors’ supporters are Republicans

(66%).

Among

Republicans, the difference in the shares who say the governor should

sign the legislation under different partisan conditions is particularly

pronounced among older and conservative Republicans.

Older

Republicans are less likely than younger Republicans to say the bill

should be signed when the governor is a Republican and Republicans are

in opposition (59% of those 50 and older say this, compared with 74% of

those under 50). There is a similar-sized age gap in the case of a

generic governor (81% vs. 69%). About nine-in-ten Republicans and

Republican leaners across all age groups say the bill should be signed

by a Democratic governor, even though most Democrats oppose the

legislation.

A similar pattern is evident by ideology: While 77%

of moderate and liberal Republicans say a bill with majority statewide

support should be signed even if most Republicans in the state oppose

it, that falls to 61% among conservative Republicans. There is no

ideological difference among Republicans when the governor and

supporters are identified as Democrats.

Among Democrats, age

differences are similar to those in the GOP: Older Democrats are

somewhat less likely than younger Democrats to back the signing of a

bill by a Democratic governor if Democrats oppose the legislation (62%

of those 50 and older, compared with 72% of those under 50) and to

support the bill’s signing in the case of a generic governor and

supporters (69% vs. 83%). But about three-quarters in all age groups say

this when the governor is identified as a Republican.

There are

no significant ideological differences among Democrats in the shares

who say the governor should sign the bill in either the Republican or

Democratic conditions. However, liberal Democrats are more likely than

conservative or moderate Democrats to say the bill should be signed when

no partisan indicators are given (86% vs. 71%).

The veto survey experiment

Only about two-in-ten say government is run for the benefit of all

A

large majority of Americans (76%) say the government is run by a few

big interests looking out for themselves; fewer than a quarter (21%) say

it is run for the benefit of all the people. Since the early 1970s,

most Americans have generally said the government is run by a few big

interests, and the share saying this is unchanged from 2015.

Most

Republicans (71%) and Democrats (84%) say the government is run by a

few big interests. More Democrats say this now than in 2015 (71% then

vs. 84% now). Views among Republicans have moved in the opposite

direction (81% then to 71% now).

Public continues to back limiting campaign spending

A

wide majority of Americans continue to believe that there should be

limits on the amount of money political candidates can spend on

campaigns: Roughly three-quarters (77%) feel that such limits are

appropriate. A somewhat smaller majority (65%) think that new campaign

finance laws could be effective in limiting the amount of money in

political campaigns. These overall views are little changed from 2015.

While

majorities of Americans in all age groups endorse limiting the amount

of money in political campaigns, those older than 30 are substantially

more likely than younger adults to hold this view (79% of those older

than 30 say that there should be limits, compared with 68% of those

under 30). Conversely, while majorities in all age groups are optimistic

about how effective new campaign finance laws would be in limiting the

role of money in politics, that sentiment is somewhat less widespread

among those 65 or older (58% say this, compared with 65% or more among

younger age groups).

Though Democrats are more likely than

Republicans to support limiting the amount of money in political

campaigns, wide majorities in both parties say there should be limits

(85% of Democrats, 71% of Republicans). Republicans are substantially

more skeptical than Democrats about the effectiveness of new laws. About

half (54%) of Republicans say that new laws could be effective while

77% of Democrats say the same.

Views about the public’s influence on government

Overall,

most adults see voting as an avenue to influence the government: 61%

say that “voting gives people like me some say about how government runs

things.”

However, on a more general measure of political

efficacy, the public is more divided: 52% say ordinary citizens can do a

lot to influence government if they make an effort, while 47% say

“there’s not much ordinary citizens can do to influence the government

in Washington.”

On both measures, younger and less-educated adults are more skeptical about the impact of participation.

The

view that voting gives people some say increases with age; while just

53% of adults under 30 say this, that compares with nearly

three-quarters of those 65 and older (73%). This age gap is seen in both

parties.

Similarly, those under 50 are less likely than their

elders (ages 50 and older) to say ordinary citizens can influence

government if they make an effort (48% vs. 56%).

Education is

also associated with a sense of political efficacy: 77% of postgraduates

say voting gives people some say, compared with two-thirds of those

with a bachelor’s degree (67%) and 57% of those with less education.