One-in-six newlyweds are married to someone of a different race or ethnicity

By

Gretchen Livingston and

Anna Brown

Terminology

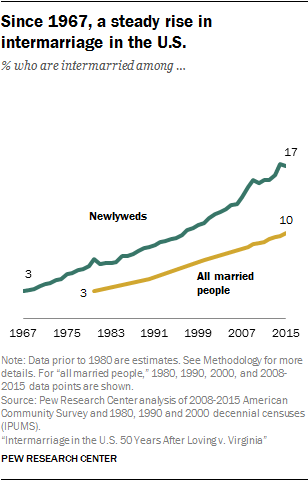

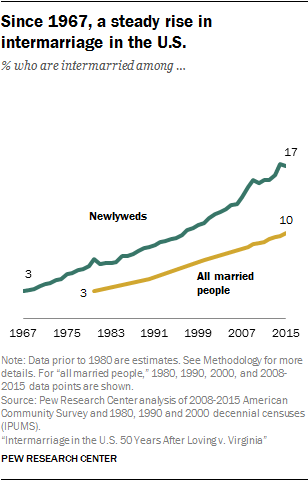

In 2015, 17% of all U.S. newlyweds had a spouse of a different race or ethnicity, marking more than a fivefold increase since 1967, when 3% of newlyweds were intermarried, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data.

2 In that year, the U.S. Supreme Court in the Loving v. Virginia case ruled that marriage across racial lines was legal throughout the country. Until this ruling, interracial marriages were forbidden in many states.

More broadly, one-in-ten married people in 2015 – not just those who recently married – had a spouse of a different race or ethnicity. This translates into 11 million people who were intermarried. The growth in intermarriage has coincided with shifting societal norms as Americans have become more accepting of marriages involving spouses of different races and ethnicities, even within their own families.

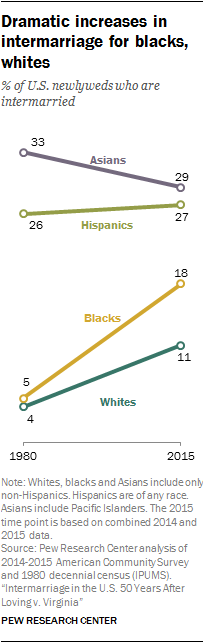

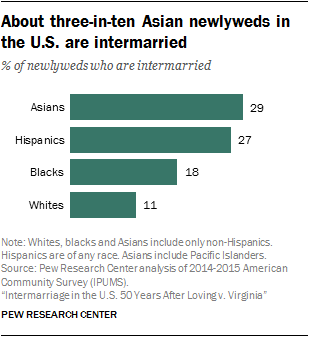

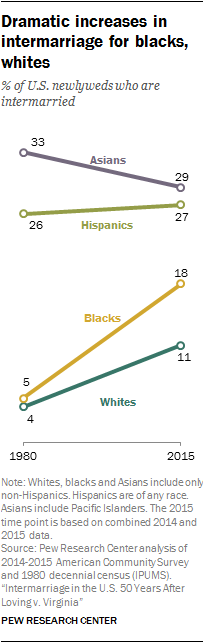

The most dramatic increases in intermarriage have occurred among black newlyweds. Since 1980, the share who married someone of a different race or ethnicity has more than tripled from 5% to 18%. White newlyweds, too, have experienced a rapid increase in intermarriage, with rates rising from 4% to 11%. However, despite this increase, they remain the least likely of all major racial or ethnic groups to marry someone of a different race or ethnicity.

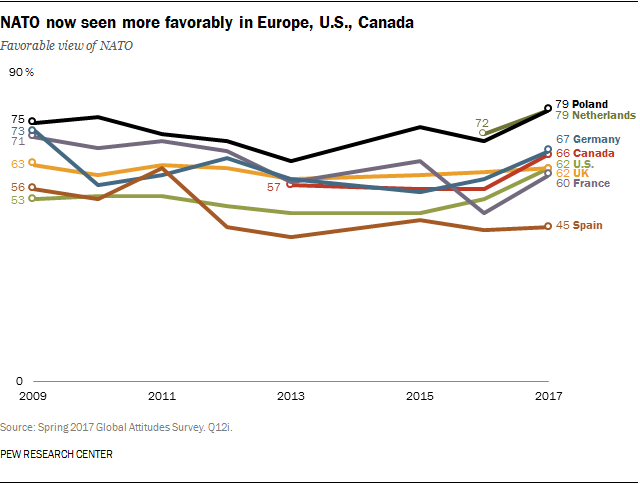

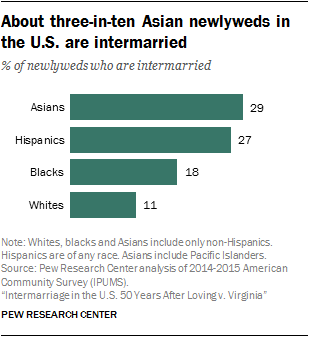

Asian and Hispanic newlyweds are by far the most likely to intermarry in the U.S. About three-in-ten Asian newlyweds

3 (29%) did so in 2015, and the share was 27% among recently married Hispanics. For these groups, intermarriage is even more prevalent among the U.S. born: 39% of U.S.-born Hispanic newlyweds and almost half (46%) of U.S.-born Asian newlyweds have a spouse of a different race or ethnicity.

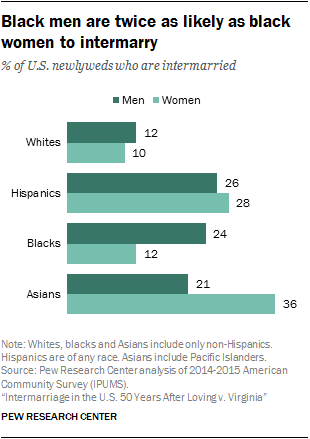

For blacks and Asians, stark gender differences in intermarriage

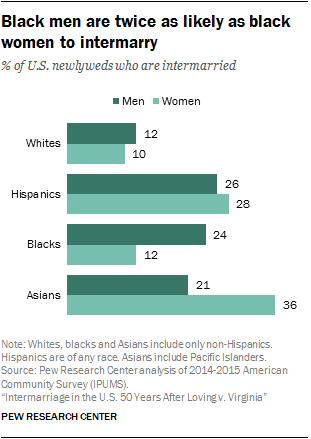

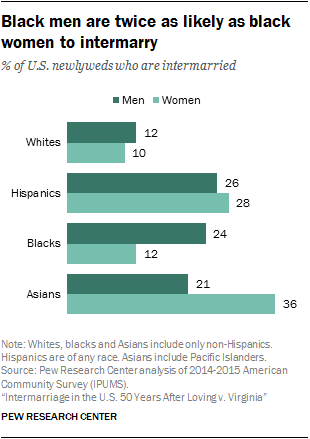

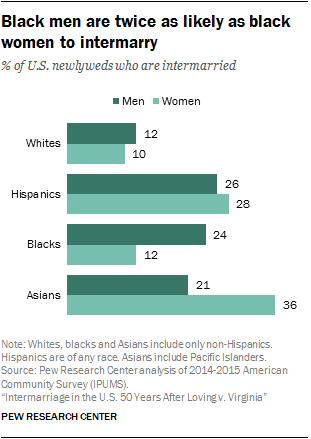

Among blacks, intermarriage is twice as prevalent for male newlyweds as it is for their female counterparts. While about one-fourth of recently married black men (24%) have a spouse of a different race or ethnicity, this share is 12% among recently married black women.

There are dramatic gender differences among Asian newlyweds as well, though they run in the opposite direction – Asian women are far more likely to intermarry than their male counterparts. In 2015, just over one-third (36%) of newlywed Asian women had a spouse of a different race or ethnicity, compared with 21% of newlywed Asian men.

In contrast, among white and Hispanic newlyweds, the shares who intermarry are similar for men and women. Some 12% of recently married white men and 10% of white women have a spouse of a different race or ethnicity, and among Hispanics, 26% of newly married men and 28% of women do.

A more diverse population and shifting attitudes are contributing to the rise of intermarriage

The rapid increases in intermarriage rates for recently married whites and blacks have played an important role in driving up the overall rate of intermarriage in the U.S. However, the growing share of the population that is

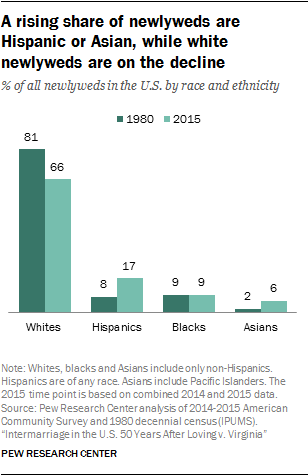

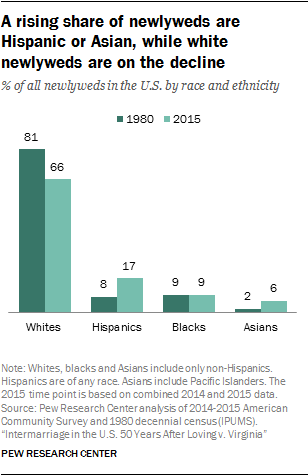

Asian or Hispanic, combined with these groups’ high rates of intermarriage, is further boosting U.S. intermarriage overall. Among all newlyweds, the share who are Hispanic has risen by 9 percentage points since 1980, and the share who are Asian has risen 4 points. Meanwhile, the share of newlyweds who are white has dropped by 15 points.

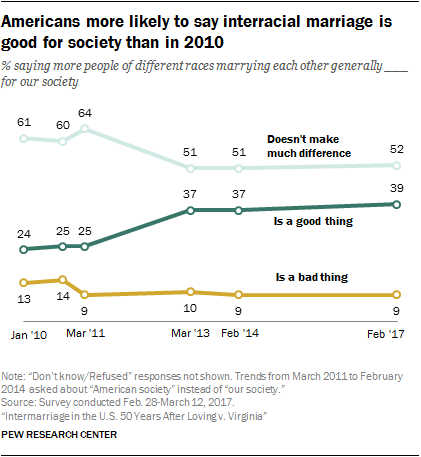

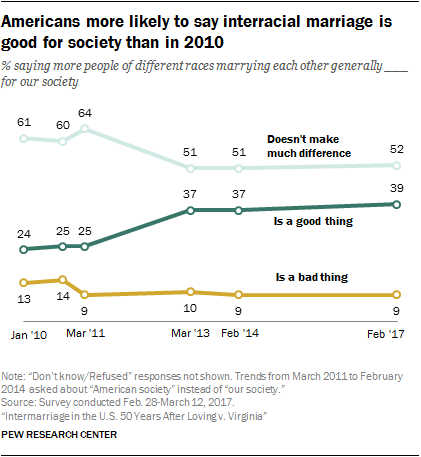

Attitudes about intermarriage are changing as well. In just seven years, the share of adults saying that the growing number of people marrying someone of a different race is good for society has risen 15 points, to 39%, according to a new Pew Research Center survey conducted Feb. 28-March 12, 2017.

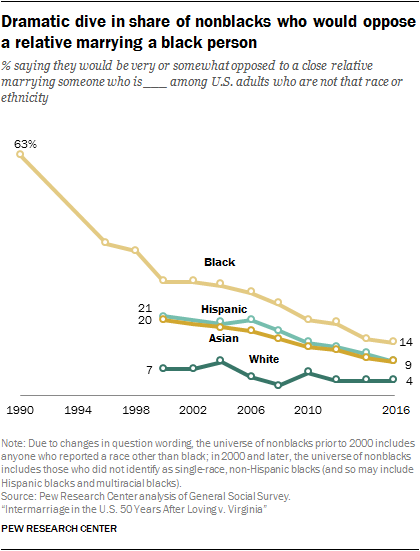

The decline in opposition to intermarriage in the longer term has been even more dramatic, a new Pew Research Center analysis of data from the

General Social Survey has found. In 1990, 63% of nonblack adults surveyed said they would be very or somewhat opposed to a close relative marrying a black person; today the figure stands at 14%. Opposition to a close relative entering into an intermarriage with a spouse who is Hispanic or Asian has also declined markedly since 2000, when data regarding those groups first became available. The share of nonwhites saying they would oppose having a family member marry a white person has edged downward as well.

Intermarriage somewhat more common among the college educated

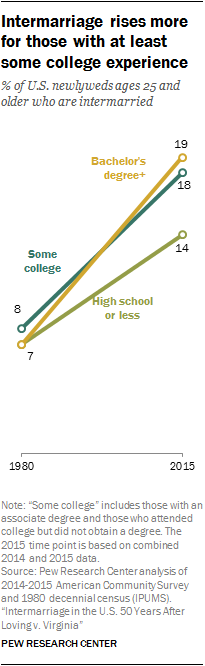

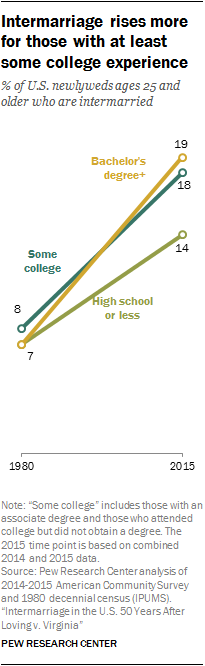

In 1980, the rate of intermarriage did not differ markedly by educational attainment among newlyweds. Since that time, however, a modest intermarriage gap has emerged. In 2015, 14% of newlyweds with a high school diploma or less were married to someone of a different race or ethnicity, compared with 18% of those with some college and 19% of those with a bachelor’s degree or more.

The educational gap is most striking among Hispanics: While almost half (46%) of Hispanic newlyweds with a bachelor’s degree were intermarried in 2015, this share drops to 16% for those with a high school diploma or less – a pattern driven partially, but not entirely, by the higher share of immigrants among the less educated. Intermarriage is also slightly more common among black newlyweds with a bachelor’s degree (21%) than those with some college (17%) or a high school diploma or less (15%).

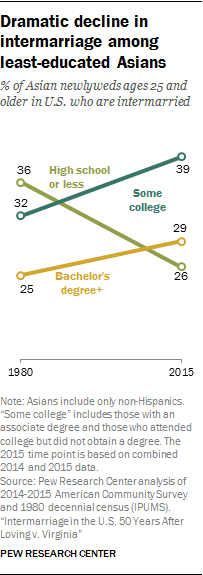

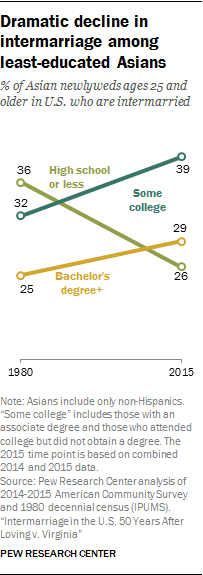

Among recently married Asians, however, the pattern is different – intermarriage is far more common among those with some college (39%) than those with either more education (29%) or less education (26%). Among white newlyweds, intermarriage rates are similar regardless of educational attainment.

Other key findings

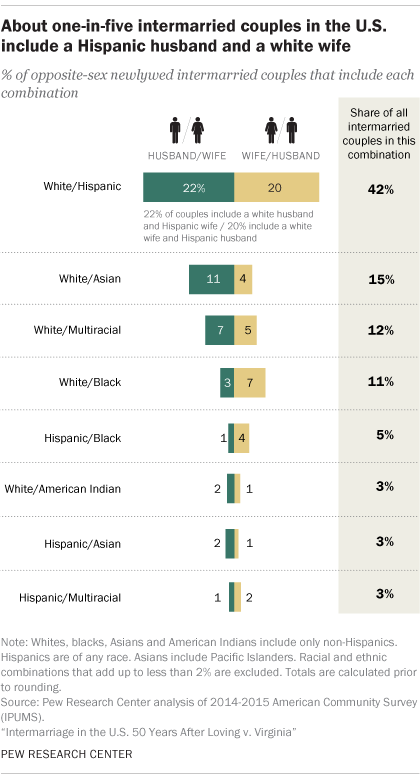

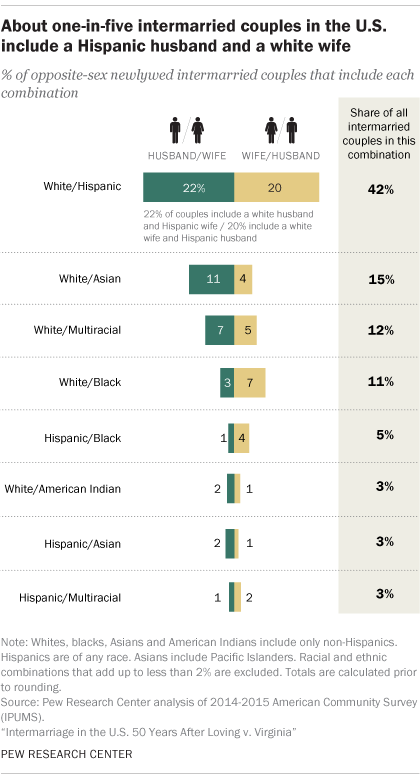

The most common racial or ethnic pairing among newlywed intermarried couples is one Hispanic and one white spouse (42%). Next most common are one white and one Asian spouse (15%) and one white and one multiracial spouse (12%).

Newlyweds living in metropolitan areas are more likely to be intermarried than those in non-metropolitan areas (18% vs. 11%). This pattern is driven entirely by whites; Hispanics and Asians are more likely to intermarry if they live in non-metro areas. The rates do not vary by place of residence for blacks.

Among black newlyweds, the gender gap in intermarriage increases with education: For those with a high school diploma or less, 17% of men vs. 10% of women are intermarried, while among those with a bachelor’s degree, black men are more than twice as likely as black women to intermarry (30% vs. 13%).

Among newlyweds, intermarriage is most common for those in their 30s (18%). Even so, 13% of newlyweds ages 50 and older are married to someone of a different race or ethnicity.

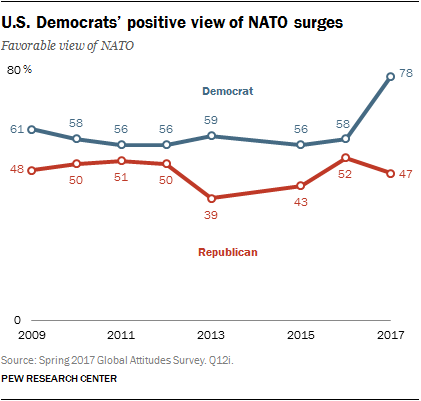

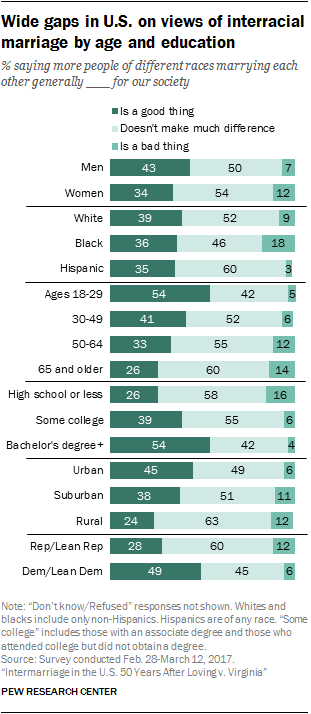

There is a sharp partisan divide in attitudes about interracial marriage. Roughly half (49%) of Democrats and independents who lean to the Democratic Party say the growing number of people of different races marrying each other is a good thing for society. Only 28% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents share that view.

1. Trends and patterns in intermarriage

By

Gretchen Livingston and

Anna Brown

In 1967, when miscegenation laws were overturned in the United States, 3% of all newlyweds were married to someone of a different race or ethnicity. Since then, intermarriage rates have steadily climbed. By 1980, the share of intermarried newlyweds had about doubled to 7%. And by 2015 the number had risen to 17%.

4 All told, more than 670,000 newlyweds in 2015 had recently entered into a marriage with someone of a different race or ethnicity. By comparison, in 1980, the first year for which detailed data are available, about 230,000 newlyweds had done so.

The long-term annual growth in newlyweds marrying someone of a different race or ethnicity has led to dramatic increases in the overall number of people who are presently intermarried – including both those who recently married and those who did so years, or even decades, earlier. In 2015, that number stood at 11 million – 10% of all married people. The share has tripled since 1980, when 3% of married people – about 3 million altogether – had a spouse of a different race or ethnicity.

Intermarriage varies by race and ethnicity

Overall increases in intermarriage have been fueled in part by rising intermarriage rates among black newlyweds and among white newlyweds. The share of recently married blacks with a spouse of a different race or ethnicity has more than tripled, from 5% in 1980 to 18% in 2015. Among recently married whites, rates have more than doubled, from 4% up to 11%.

At the same time, intermarriage has ticked down among recently married Asians and remained more or less stable among Hispanic newlyweds. Even though intermarriage has not been increasing for these two groups, they remain far more likely than black or white newlyweds to marry someone of a different race or ethnicity. About three-in-ten Asian newlyweds (29%) have a spouse of a different race or ethnicity. The same is true of 27% of Hispanics.

For newly married Hispanics and Asians, the likelihood of intermarriage is closely related to whether they were born in the U.S. or abroad. Among the half of Hispanic newlyweds who are immigrants, 15% married a non-Hispanic. In comparison, 39% of the U.S. born did so. The pattern is similar among Asian newlyweds, three-fourths of whom are immigrants. While 24% of foreign-born Asian newlyweds have a spouse of a different race or ethnicity, this share rises to 46% among the U.S. born.

The changing racial and ethnic profile of U.S. newlyweds is linked to growth in intermarriage

Significant growth in the

Hispanic and Asian populations in the U.S. since 1980, coupled with the high rates of intermarriage among Hispanic and Asian newlyweds, has been an important factor driving the rise in intermarriage. Since that time, the share of all newlyweds that were Hispanic rose 9 percentage points, from 8% to 17%, and the share that were Asian grew from 2% to 6%. At the same time, the share of white newlyweds declined by 15 points and the share of black newlyweds held steady.

The size of each racial and ethnic group can also influence intermarriage rates by affecting the pool of potential marriage partners in the “marriage market,” which consists of all newlyweds and all unmarried adults combined.

5 For example, whites, who comprise the largest share of the U.S. population, may be more likely to marry someone of the same race simply because most potential partners are white. And members of smaller racial or ethnic groups may be more likely to intermarry because relatively few potential partners share their race or ethnicity.

But size alone cannot totally explain intermarriage patterns. Hispanics, for instance, made up 17% of the U.S. marriage market in 2015, yet their newlywed intermarriage rates were comparable to those of Asians, who comprised only 5% of the marriage market. And while the share of the marriage market comprised of Hispanics has grown markedly since 1980, when it was 6%, their intermarriage rate has remained stable. Perhaps more striking – the share of blacks in the marriage market has remained more or less constant (15% in 1980, 16% in 2015), yet their intermarriage rate has more than tripled.

For blacks and Asians, big gender gaps in intermarriage

While there is no overall gender difference in intermarriage among newlyweds

6, starkly different gender patterns emerge for some major racial and ethnic groups.

One of the most dramatic patterns occurs among black newlyweds: Black men are twice as likely as black women to have a spouse of a different race or ethnicity (24% vs. 12%). This gender gap has been a long-standing one – in 1980, 8% of recently married black men and 3% of their female counterparts were married to someone of a different race or ethnicity.

A significant gender gap in intermarriage is apparent among Asian newlyweds as well, though the gap runs in the opposite direction: Just over one-third (36%) of Asian newlywed women have a spouse of a different race or ethnicity, while 21% of Asian newlywed men do. A substantial gender gap in intermarriage was also present in 1980, when 39% of newly married Asian women and 26% of their male counterparts were married to someone of a different race or ethnicity.

Among Asian newlyweds, these gender differences exist for both immigrants (15% men, 31% women) and the U.S. born (38% men, 54% women). While the gender gap among Asian immigrants has remained relatively stable, the gap among the U.S. born has widened substantially since 1980, when intermarriage stood at 46% among newlywed Asian men and 49% among newlywed Asian women.

Among white newlyweds, there is no notable gender gap in intermarriage – 12% of men and 10% of women had married someone of a different race or ethnicity in 2015. The same was true in 1980, when 4% of recently married men and 4% of recently married women had intermarried.

As is the case among whites, intermarriage is about equally common for newlywed Hispanic men and women. In 2015, 26% of recently married Hispanic men were married to a non-Hispanic, as were 28% of their female counterparts. These intermarriage rates have changed little since 1980.

A growing educational gap in intermarriage

In 2015 the likelihood of marrying someone of a different race or ethnicity was somewhat higher among newlyweds with at least some college experience than among those with a high school diploma or less. While 14% of the less-educated group was married to someone of a different race or ethnicity, this share rose to 18% among those with some college experience and 19% among those with at least a bachelor’s degree. This marks a change from 1980, when there were virtually no educational differences in the likelihood of intermarriage among newlyweds.

7 The same patterns and trends emerge when looking separately at newlywed men and women; there are no overall gender differences in intermarriage by educational attainment. In 2015, 13% of recently married men with a high school diploma or less and 14% of women with the same level of educational attainment had a spouse of another race or ethnicity, as did 19% of recently married men with some college and 18% of comparable women. Among newlyweds with a bachelor’s degree, 20% of men and 18% of women were intermarried.

Strong link between education and intermarriage for Hispanics

The association between intermarriage and educational attainment among newlyweds varies across racial and ethnic groups. For instance, among Hispanic newlyweds, higher levels of education are strongly linked with higher rates of intermarriage. While 16% of those with a high school diploma or less are married to a non-Hispanic, this share more than doubles to 35% among those with some college. And it rises to 46% for those with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

This pattern may be partly driven by the fact that Hispanics with low levels of education are disproportionately immigrants who are in turn less likely to intermarry. However, rates of intermarriage increase as education levels rise for both the U.S. born and the foreign born: Among immigrant Hispanic newlyweds, intermarriage rates range from 9% among those with a high school diploma or less up to 33% for those with a bachelor’s degree or more; and among the U.S. born, rates range from 32% for those with a high school diploma or less up to 56% for those with a bachelor’s degree or more.

There is no significant gender gap in intermarriage among newly married Hispanics across education levels or over time.

For blacks, intermarriage has increased most among those with no college experience

For black newlyweds, intermarriage rates are slightly higher among those with a bachelor’s degree or more (21%). Among those with some college, 17% have married someone of a different race or ethnicity, as have 15% of those with a high school diploma or less.

Intermarriage has risen dramatically at all education levels for blacks, with the biggest proportional increases occurring among those with the least education. In 1980, just 5% of black newlyweds with a high school diploma or less had intermarried – a number that has since tripled. Rates of intermarriage have more than doubled at higher education levels, from 7% among those with some college experience and 8% among those with a bachelor’s degree.

Among black newlyweds, there are distinct gender differences in intermarriage across education levels. In 2015, the rate of intermarriage varied by education only slightly among recently married black women: 10% of those with some college or less had intermarried compared with 13% of those with a bachelor’s degree or more. Meanwhile, among newly married black men, higher education is clearly associated with higher intermarriage rates. While 17% of those with a high school diploma or less had a spouse of a different race or ethnicity in 2015, this share rose to 24% for those with some college and to 30% for those with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Asians with some college are the most likely to intermarry

While intermarriage is associated with higher education levels for Hispanics and blacks, this is not the case among Asian newlyweds. Those with some college are by far the most likely to have married someone of a different race or ethnicity – 39% in 2015 had done so, compared with about one-fourth (26%) of those with only a high school diploma or less and 29% of those with a bachelor’s degree.

This pattern reflects dramatic changes since 1980. At that time, Asians with a high school diploma or less were the most likely to intermarry; 36% did so, compared with 32% of those with some college and 25% of those with a bachelor’s degree.

Asian newlyweds with some college are somewhat less likely to be immigrants, and this may contribute to the higher rates of intermarriage for this group. However, even among recently married Asian immigrants with some college, 33% had intermarried, compared with 22% of those with a high school diploma or less and 23% of those with a bachelor’s degree or more.

8 There are sizable gender gaps in intermarriage across all education levels among recently married Asians, with the biggest proportional gap occurring among those with a high school diploma or less. Newlywed Asian women in this category are more than twice as likely as their male counterparts to have a spouse of a different race or ethnicity (36% vs. 14%). The gaps decline somewhat at higher education levels, but even among college graduates, 36% of women are intermarried compared with 21% of men.

Among whites, little difference in intermarriage rates by education level

Among white newlyweds, the likelihood of intermarrying is fairly similar regardless of education level. One-in-ten of those with a high school diploma or less have a spouse of another race or ethnicity, as do 11% of those with some college experience and 12% of those with at least a bachelor’s degree. Rates don’t vary substantially among white newlywed men or women with some college or less, though men with a bachelor’s degree are somewhat more likely to intermarry than comparable women (14% vs. 10%).

Intermarriage is slightly less common at older ages

Nearly one-in-five newlyweds in their 30s (18%) are married to someone of a different race or ethnicity, as are 16% of those in their teens or 20s and those in their 40s. Among newlyweds ages 50 and older, many of whom are likely

remarrying, the share intermarried is a bit lower (13%).

The lower rate of intermarriage among older newlyweds in 2015 is largely attributable to a lower rate among women. While intermarriage rates ranged from 16% to 18% among women younger than 50, rates dropped to 12% among those 50 and older. Among recently married men, however, intermarriage did not vary substantially by age.

Intermarriage varies little by age for white and Hispanic newlyweds, but more striking patterns emerge among black and Asian newlyweds. While 22% of blacks ages 15 to 29 are intermarried, this share drops incrementally, reaching a low of 13% among those ages 50 years or older. Among Asian newlyweds, a different pattern emerges. Intermarriage rises steadily from 25% among those ages 15 to 29 years to 42% among those in their 40s. For those 50 years and older, however, the rate drops to 32%.

A closer look at intermarriage among Asian newlyweds reveals that the overall age pattern of intermarriage – with the highest rates among those in their 40s – is driven largely by the dramatic age differences in intermarriage among newly married Asian women. More than half of newlywed Asian women in their 40s intermarry (56%), compared with 42% of those in their 30s and 46% of those 50 and older. Among Asian newlywed women younger than 30, 29% are intermarried. Among recently married Asian men, the rate of intermarriage doesn’t vary as much across age groups: 26% of those in their 40s are intermarried, compared with 20% of those in their 30s and those 50 and older. Among Asian newlywed men in their teens or 20s, 18% are intermarried.

Though the overall rate of intermarriage does not differ markedly by age among white newlyweds, a gender gap emerges at older ages. While recently married white men and women younger than 40 are about equally likely to be intermarried, a 4-point gap emerges among those in their 40s (12% men, 8% women), and recently married white men ages 50 and older are about twice as likely as their female counterparts to be married to someone of a different race or ethnicity (11% vs. 6%).

A similar gender gap in intermarriage emerges at older ages for Hispanic newlyweds. However, in this case it is newly married Hispanic women ages 50 and older who are more likely to intermarry than their male counterparts (32% vs. 26%). Among black newlyweds, men are consistently more likely than women to intermarry at all ages.

In metro areas, almost one-in-five newlyweds are intermarried

Intermarriage is more common among newlyweds in the nation’s metropolitan areas, which are located in and around large urban centers, than it is in non-metro areas

9, which are typically more rural. About 18% of those living in a metro area are married to someone of a different race or ethnicity, compared with 11% of those living outside of a metro area. In 1980, 8% of newlyweds in metro areas were intermarried, compared with 5% of those in non-metro areas.

There are likely many reasons that intermarriage is more common in metro areas than in more rural areas. Attitudinal differences may play a role. In urban areas, 45% of adults say that more people of different races marrying each other is a good thing for society, as do 38% of those living in suburban areas (which are typically included in what the Census Bureau defines as metro areas). Among people living in rural areas, which are typically non-metro areas, fewer (24%) share this view.

Another factor is the difference in the racial and ethnic composition of each type of area. Non-metro areas have a relatively large share of white newlyweds (83% vs. 62% in metro areas), and whites are far less likely to intermarry than those of other races or ethnicities. At the same time, metro areas have larger shares of Hispanics and Asians, who have very high rates of intermarriage. While 26% of newlyweds in metro areas are Hispanic or Asian, this share is 10% for newlyweds in non-metro areas.

The link between place of residence and intermarriage varies dramatically for different racial and ethnic groups. The increased racial and ethnic diversity of metro areas means that the supply of potential spouses, too, will likely be more diverse. This fact may contribute to the higher rates of intermarriage for white metro area newlyweds, since the marriage market includes a relatively larger share of people who are nonwhite. Indeed, recently married whites are the only major group for which intermarriage is higher in metro areas. White newlyweds in metro areas are twice as likely as those in non-metro areas to have a spouse of a different race or ethnicity (12% vs. 6%).

In contrast, for Asians, the likelihood of intermarrying is higher in non-metro areas (47%) than metro areas (28%), due in part to the fact that the share of Asians in the marriage market is lower in non-metro areas. The same holds true among Hispanics. About one-third (32%) of Hispanic newlyweds in non-metro areas are intermarried compared with 25% in metro areas.

Among black newlyweds, intermarriage rates are identical for those living in metro and non-metro areas (18% each), even though blacks are a larger share of the marriage market in metro areas than in non-metro areas.

The largest share of intermarried couples include one Hispanic and one white spouse

While the bulk of this report focuses on patterns of intermarriage among all newly married individuals, shifting the analysis to the racial and ethnic composition of intermarried newlywed couples shows that the most prevalent form of intermarriage involves one Hispanic and one white spouse (42%). While this share is relatively high, it marks a decline from 1980, when more than half (56%) of all intermarried couples included one Hispanic and one white person.

The next most prevalent couple type in 2015 among those who were intermarried included one Asian and one white spouse (15%). Couples including one black and one white spouse accounted for about one-in-ten (11%) intermarried couples in 2015, a share that has held more or less steady since 1980.

That intermarriage patterns vary by gender becomes apparent when looking at a more detailed profile of intermarried couples that identifies the race or ethnicity of the husband separately from the race or ethnicity of the wife. A similar share of intermarried couples involve a white man and a Hispanic woman (22%) as involve a white woman and a Hispanic man (20%).

However, more notable gender differences emerge for some of the other couple profiles. For instance, while 11% of all intermarried couples involve a white man and an Asian woman, just 4% of couples include a white woman and an Asian man. And while about 7% of intermarried couples include a black man and a white woman, only 3% include a black woman and a white man.

2. Public views on intermarriage

By

Gretchen Livingston and

Anna Brown

As intermarriage grows more prevalent in the United States, the public has become more accepting of it. A growing share of adults say that the trend toward more people of different races marrying each other is generally a good thing for American society.

10 At the same time, the share saying they would oppose a close relative marrying someone of a different race has fallen dramatically.

A new Pew Research Center survey finds that roughly four-in-ten adults (39%) now say that more people of different races marrying each other is good for society – up significantly from 24% in 2010. The share saying this trend is a bad thing for society is down slightly over the same period, from 13% to 9%. And the share saying it doesn’t make much of a difference for society is also down, from 61% to 52%. Most of this change occurred between 2010 and 2013; opinions have remained essentially the same since then.

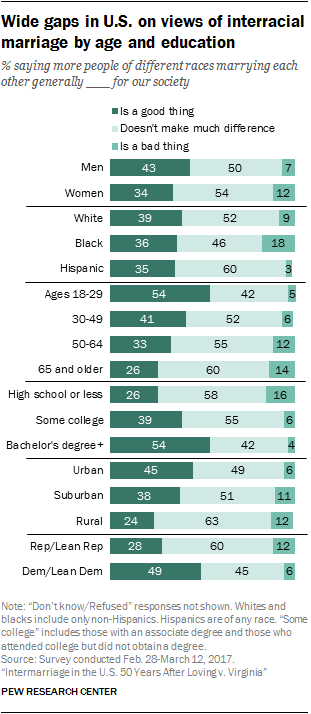

Attitudes about interracial marriage vary widely by age. For example, 54% of those ages 18 to 29 say that the rising prevalence of interracial marriage is good for society, compared with about a quarter of those ages 65 and older (26%). In turn, older Americans are more likely to say that this trend doesn’t make much difference (60% of those ages 65 and older, compared with 42% of those 18 to 29) or that it is bad for society (14% vs. 5%, respectively).

Views on interracial marriage also differ by educational attainment. Americans with at least a bachelor’s degree are much more likely than those with less education to say more people of different races marrying each other is a good thing for society (54% of those with a bachelor’s degree or more vs. 39% of those with some college education and 26% of those with a high school diploma or less). Among adults with a high school diploma or less, 16% say this trend is bad for society, compared with 6% of those with some college experience and 4% of those with at least a bachelor’s degree.

Men are more likely than women to say the rising number of interracial marriages is good for society (43% vs. 34%) while women are somewhat more likely to say it’s a bad thing (12% vs. 7%). This is a change from 2010, when men and women had almost identical views. Then, about a quarter of each group (23% of men and 24% of women) said this was a good thing and 14% and 12%, respectively, said it was a bad thing.

Blacks (18%) are more likely than whites (9%) and Hispanics (3%) to say more people of different races marrying each other is generally a bad thing for society, though there are no significance differences by race or ethnicity on whether it is a good thing for society.

11 Among Americans who live in urban areas, 45% say this trend is a good thing for society, as do 38% of those in the suburbs; lower shares among those living in rural areas share this view (24%). In turn, rural Americans are more likely than those in urban or suburban areas to say interracial marriage doesn’t make much difference for society (63% vs. 49% and 51%, respectively).

The view that the rise in the number of interracial marriages is good for society is particularly prevalent among Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents; 49% in this group say this, compared with 28% of Republicans and those who lean Republican. The majority of Republicans (60%) say it doesn’t make much of a difference, while 12% say this trend is bad for society. Among Democrats, 45% say it doesn’t make much difference while 6% say it’s bad thing. This difference persists when controlling for race. Among whites, Democrats are still much more likely than Republicans to say more interracial marriages are a good thing for society.

Americans are now much more open to the idea of a close relative marrying someone of a different race

Just as views about the impact of interracial marriage on society have evolved, Americans’ attitudes about what is acceptable within their own family have changed. A new Pew Research Center analysis of

General Social Survey (GSS) data finds that the share of U.S. adults saying they would be opposed to a close relative marrying someone of a different race or ethnicity has fallen since 2000.

In 2000, 31% of Americans said they would oppose an intermarriage in their family.

12 That share dropped to 9% in 2002 but climbed again to 16% in 2008. It has fallen steadily since, and now one-in-ten Americans say they would oppose a close relative marrying someone of a different race or ethnicity.

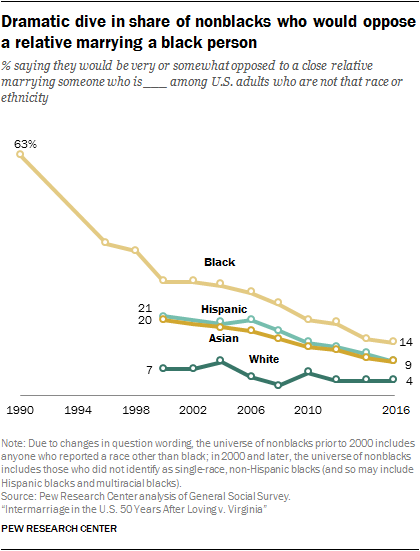

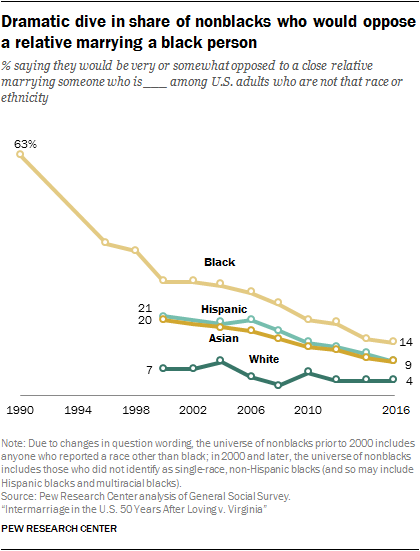

These modest changes over time belie much larger shifts when it comes to attitudes toward marrying people of specific races. As recently as 1990, roughly six-in-ten nonblack Americans (63%) said they would be opposed to a close relative marrying a black person. This share had been cut about in half by 2000 (at 30%), and halved again since then to stand at 14% today.

13 In 2000, one-in-five non-Asian adults said they would be opposed to a close relative marrying an Asian person, and a similar share of non-Hispanic adults (21%) said the same about a family member marrying a Hispanic person. These shares have dropped to around one-in-ten for each group in 2016.

Among nonwhite adults, the share saying they would be opposed to a relative marrying a white person stood at 4% in 2016, down marginally from 7% in 2000 when the GSS first included this item.

While these views have changed substantially over time, significant demographic gaps persist. Older adults are especially likely to oppose having a family member marry someone of a different race or ethnicity. Among those ages 65 and older, about one-in-five (21%) say they would be very or somewhat opposed to an intermarriage in their family, compared with one-in-ten of those ages 50 to 64, 7% of those 30 to 49 and only 5% of those 18 to 29.

Whites (12%) and blacks (9%) are more likely than Hispanics (3%) to say they would oppose a close relative marrying someone of a different race or ethnicity. Men are somewhat more likely than women to say this as well (13% vs. 8%).

Americans with less education are more likely to oppose an intermarriage in their family: 14% of adults with a high school diploma or less education say this, compared with 8% of those with some college education and those with a bachelor’s degree, each.

There are also large differences by political party, with Republicans and those who lean toward the Republican Party roughly twice as likely as Democrats and Democratic leaners to say they would oppose a close relative marrying someone of a different race (16% vs. 7%). Controlling for race, the gap is the same: Among whites, 17% of Republicans and 8% of Democrats say they would oppose an intermarriage in their family.