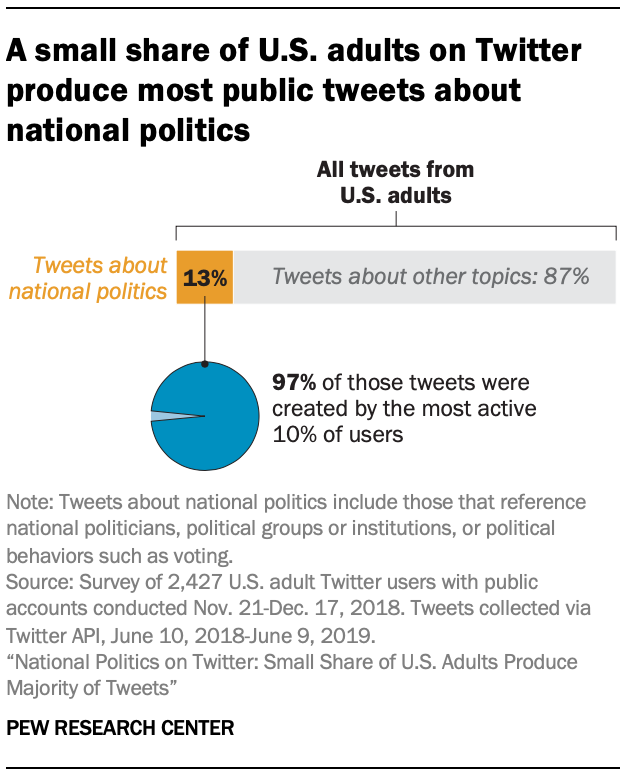

The social media platform Twitter plays a prominent role in how politicians, media outlets and advocacy organizations promote their agendas and engage with political issues. Although these entities represent a highly visible portion of the political Twitter ecosystem, less is known about the political tweeting habits of the 22% of the American public that uses Twitter. A new Pew Research Center analysis sheds light on this question by collecting and analyzing the tweets of a random sample of U.S. adults with public Twitter accounts1 over a period of one year surrounding the 2018 midterm elections (from June 10, 2018, through June 9, 2019).

The

findings of this analysis paint a nuanced picture of just how prevalent

political speech is among U.S. adults on Twitter. On one hand, 39% of

users with public accounts tweeted at least once about national politics

– which includes mentions of national politicians, institutions or

groups, as well as civic behaviors such as voting – over the study

period. On the other hand, national politics is a relatively small

element of the total Twitter conversation among U.S. adults. Content

explicitly related to these issues made up just 13% of all tweets

analyzed over the year studied.

The

findings of this analysis paint a nuanced picture of just how prevalent

political speech is among U.S. adults on Twitter. On one hand, 39% of

users with public accounts tweeted at least once about national politics

– which includes mentions of national politicians, institutions or

groups, as well as civic behaviors such as voting – over the study

period. On the other hand, national politics is a relatively small

element of the total Twitter conversation among U.S. adults. Content

explicitly related to these issues made up just 13% of all tweets

analyzed over the year studied. And as our previous research found to be true of Twitter content more broadly, this analysis finds that a small share of users produce the vast majority of content related to national politics: 97% of tweets from U.S. adults that mentioned national politics over the study period came from just 10% of users.

A total of 2,427 respondents with public Twitter accounts participated in the survey; collectively, they produced more than 1.1 million tweets over the course of the study period (June 10, 2018-June 9, 2019). The Center used a guided machine learning model to classify each of these 1.1 million tweets as related to national politics or not (see sidebar and methodology for more details on this process and the types of content that are included in our definition of political tweets).

The study design helps to illustrate which types of users are most drawn to tweet about national politics in the first place. Most notably, those with intense views of President Donald Trump are among the most prolific political tweeters.

Tweets from users who strongly disapprove of Trump are especially prominent: This group generates 80% of all tweets from U.S. adults and 72% of tweets mentioning national politics. Those who strongly approve of Trump (who produce 11% of all tweets from U.S. adults) create 25% of tweets mentioning national politics. Taken together, strong disapprovers and strong approvers of Trump generate 97% of all tweets mentioning national politics from U.S. adults on Twitter. In interpreting these results, it is important to note that it was beyond the scope of this study to classify the share of tweets that explicitly mentioned the president, or that expressed particular views about his administration’s policies. And as noted above, the definition of political tweets used in this analysis includes a wide range of phrases and hashtags not related to Trump.

The prevalence of tweets mentioning national politics from U.S. adults who strongly disapprove of Trump is tied to two factors. First, this group makes up a larger share of Twitter users than of the general public. The share of U.S. adults on Twitter who strongly disapprove of Trump (55%) is 7 percentage points higher than the share of the general public that holds this view (48%). Second, this group is more likely to tweet about national politics than others on Twitter. Strong disapprovers of Trump make up 55% of all U.S. adults on Twitter, but their frequency of tweeting about national politics results in them generating 72% of all the tweets about this topic from U.S. adults.

By contrast, U.S. adults who strongly approve of Trump are underrepresented on Twitter relative to their presence in the population as a whole: 15% of Twitter users strongly approve of Trump, compared with 29% of the general public. However, those who strongly approve of Trump are similar to those who strongly disapprove of him in that they also are more likely than other groups to tweet about national politics. Twitter users who strongly approve of Trump generate 25% of the political tweets that come from U.S. adults – larger than the share of all Twitter users they represent (15%).

Those who tweet about politics differ from those who avoid the topic or tweet infrequently

Pairing

a survey with an examination of the Twitter behaviors of U.S. adults

also allows for a comparison of the attitudes and characteristics of

political tweeters with those of other Twitter users. Political tweeters

– defined as those who tweeted at least five times in total, and at

least twice about national politics, over the year of the study period –

are almost twice as likely as other Twitter users to say the people

they follow on Twitter have political beliefs similar to their own (38%

of political tweeters say this, compared with around one-in-five among

nonpolitical tweeters). By contrast, nonpolitical tweeters are more

likely to say they aren’t sure about the political beliefs of the people

they follow or that they follow people with a mix of political views.

Pairing

a survey with an examination of the Twitter behaviors of U.S. adults

also allows for a comparison of the attitudes and characteristics of

political tweeters with those of other Twitter users. Political tweeters

– defined as those who tweeted at least five times in total, and at

least twice about national politics, over the year of the study period –

are almost twice as likely as other Twitter users to say the people

they follow on Twitter have political beliefs similar to their own (38%

of political tweeters say this, compared with around one-in-five among

nonpolitical tweeters). By contrast, nonpolitical tweeters are more

likely to say they aren’t sure about the political beliefs of the people

they follow or that they follow people with a mix of political views. And greater engagement with national politics on Twitter is tied to political behaviors that extend beyond the social media platform. Those who tweet about politics are more likely than other users to report engaging in a variety of political activities, such as attending rallies and contacting elected officials.

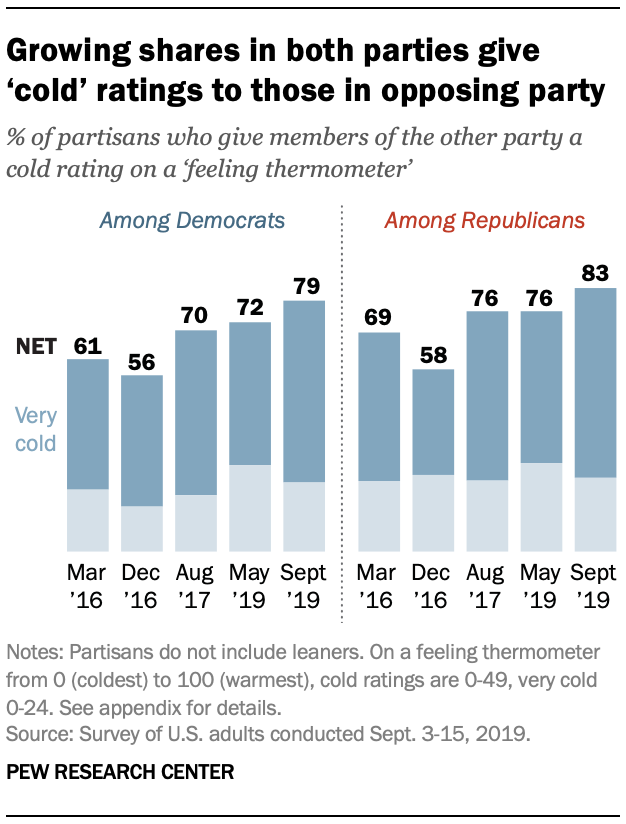

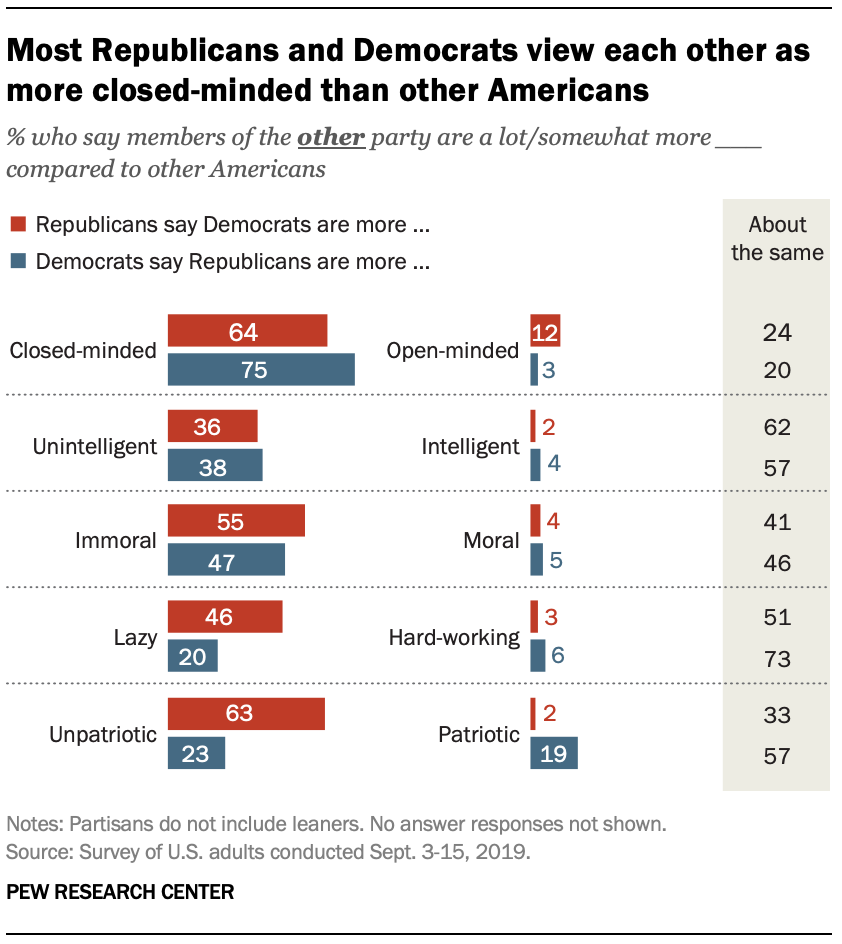

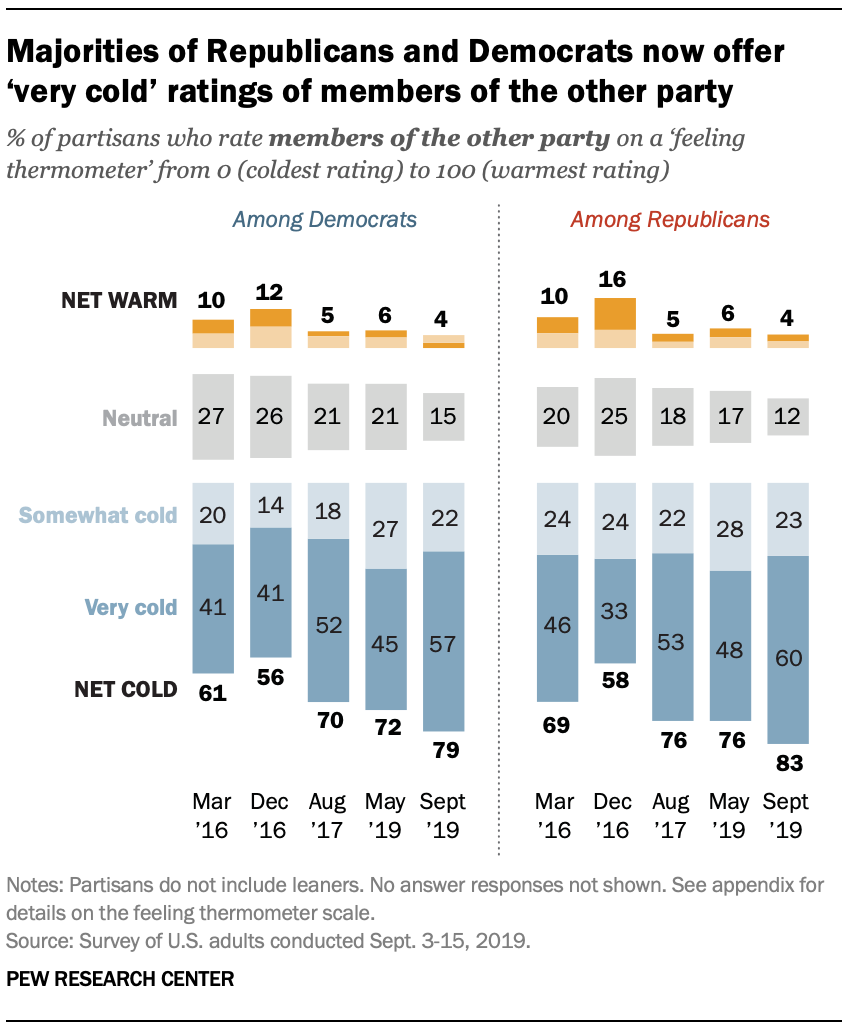

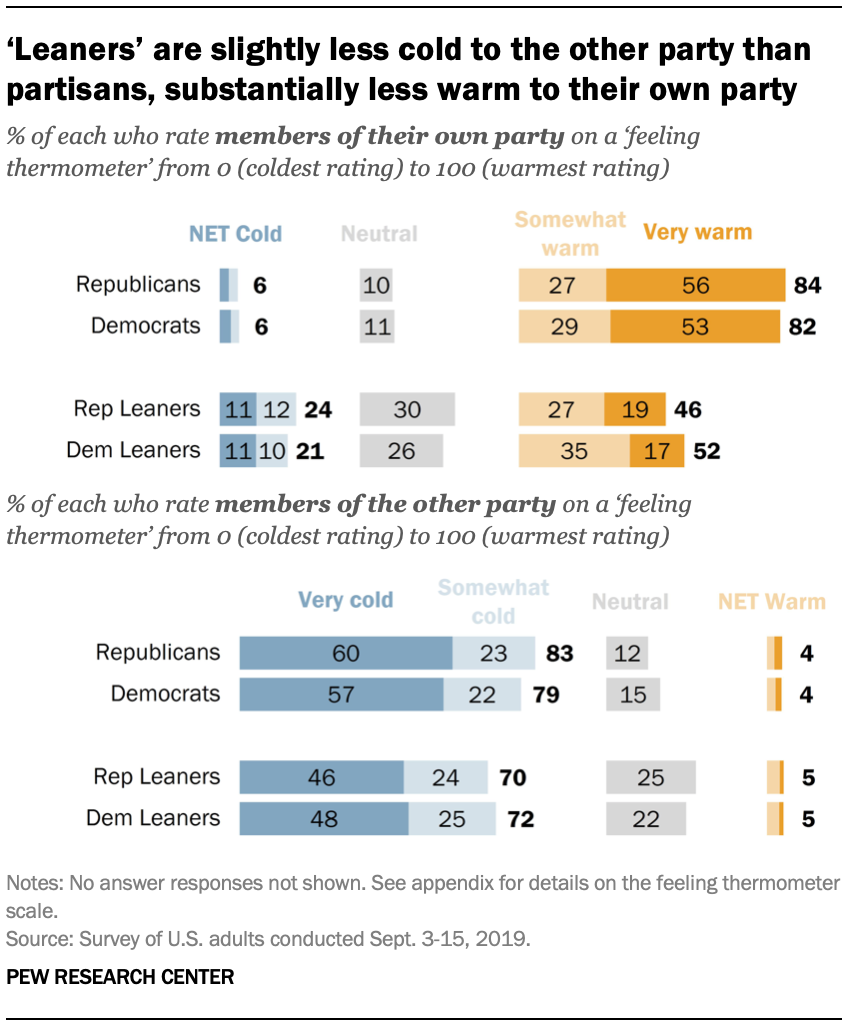

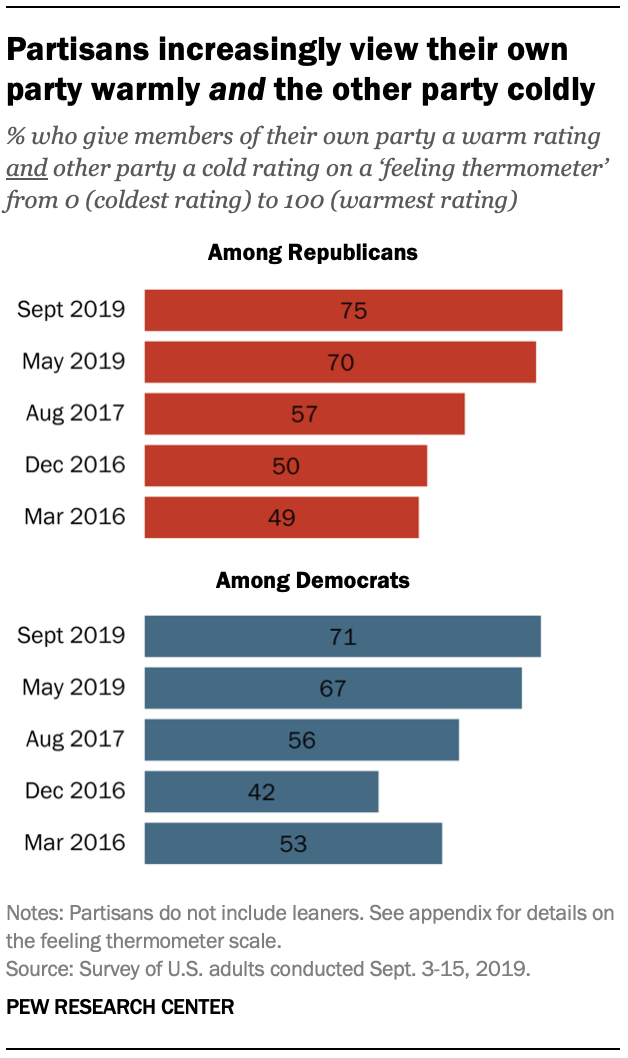

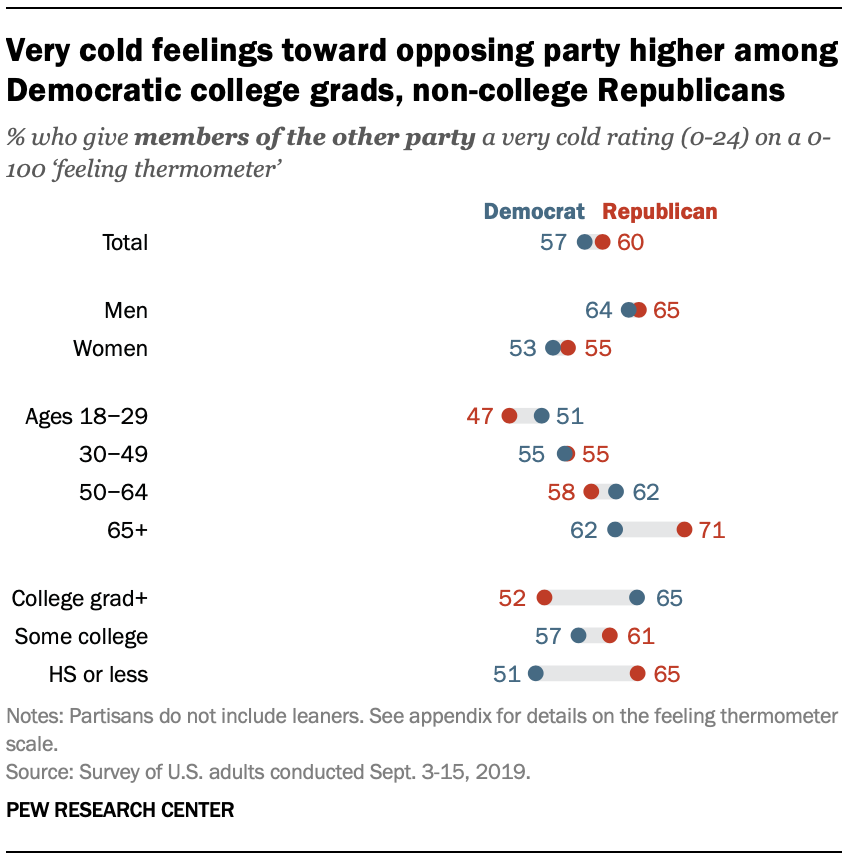

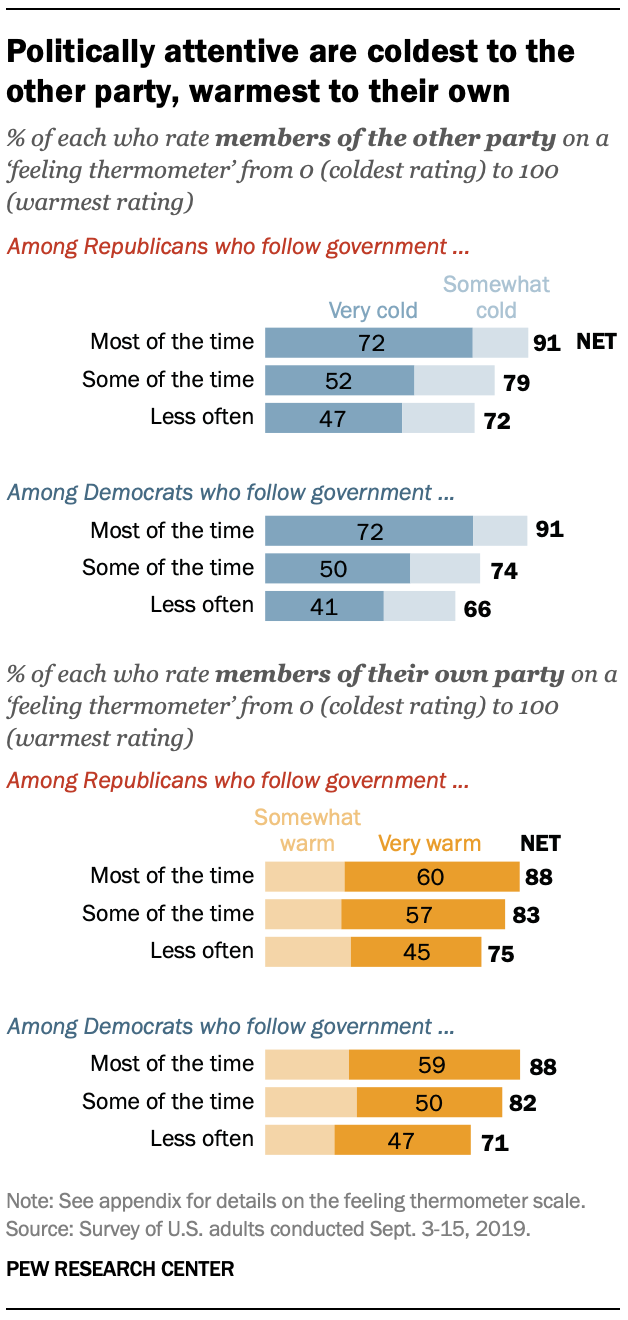

Prior research by the Center has found that politically engaged Republicans and Democrats in the general public are more likely than less-engaged partisans to hold a range of negative attitudes about the opposing party. And this new analysis indicates that partisans who tweet about national political issues tend to have colder views of the opposing political party relative to other users who are less politically active on the site. This difference is especially pronounced among Republicans: 51% of Republicans and those who lean toward the Republican Party who tweet about national politics give a very cold rating to Democrats, compared with about a third of Republicans on Twitter who don’t tweet about politics.

Measuring whether or not tweets talk about ‘national politics’

A central challenge of identifying and analyzing political content (on Twitter or elsewhere) is that many types of speech or online activity might be deemed “political” in some form or fashion. The general concept of politics might encompass numerous actors at the federal, state or local levels, as well as issue-specific concepts ranging from abortion to immigration to taxes. In an effort to create a broadly reasonable and functional definition of what tweets are considered “political” for the purposes of this analysis, we chose to focus on tweets that specifically mention or engage with national politics.

For the purposes of this analysis, a tweet is considered to discuss national politics if it mentions or expresses support or opposition toward national politicians or elected officials, political parties, ideological groups or political institutions, or specific political behaviors like voting. This definition of political content excludes tweets that are solely about state or local politics. It also does not include general discussions of issues (even if those issues may be of national interest) unless they also include a mention of a national politician, party, institution or organized political behavior.

Researchers identified tweets about national politics using a two-step process. First, they used a custom text classification model to classify political tweets based on the language used in the tweet. As an example, tweets encouraging Americans to vote in a national election or using common political hashtags would be classified as political during this step. Second, researchers searched for mentions of the Twitter usernames of members of Congress and other notable national politicians. All tweets mentioning these usernames were classified as political. As a result, tweets that engage with national politicians on Twitter are classified as political even if the content of the tweet is otherwise not obviously political. For instance, a brief reply to a member of Congress saying “happy birthday” would be classified as being related to national politics.

It is important to note that this method may fail to correctly classify tweets that use irony, sarcasm, memes or images to convey feelings or ideas about national politics. In other words, this analysis captures only the specific subset of the larger political conversation on Twitter that involves overt or explicit discussion of, or engagement with, U.S. national politics.

Despite the bounded nature of this definition, the estimates produced by this model largely align with the self-reported tweeting behavior of participants in the survey. For those who say they never tweet about politics or have, but not recently, the model estimates that just 2% of their tweets mention national politics. But among those who say they have tweeted about politics within the previous 30 days, an estimated 26% of their tweets mentioned national politics.

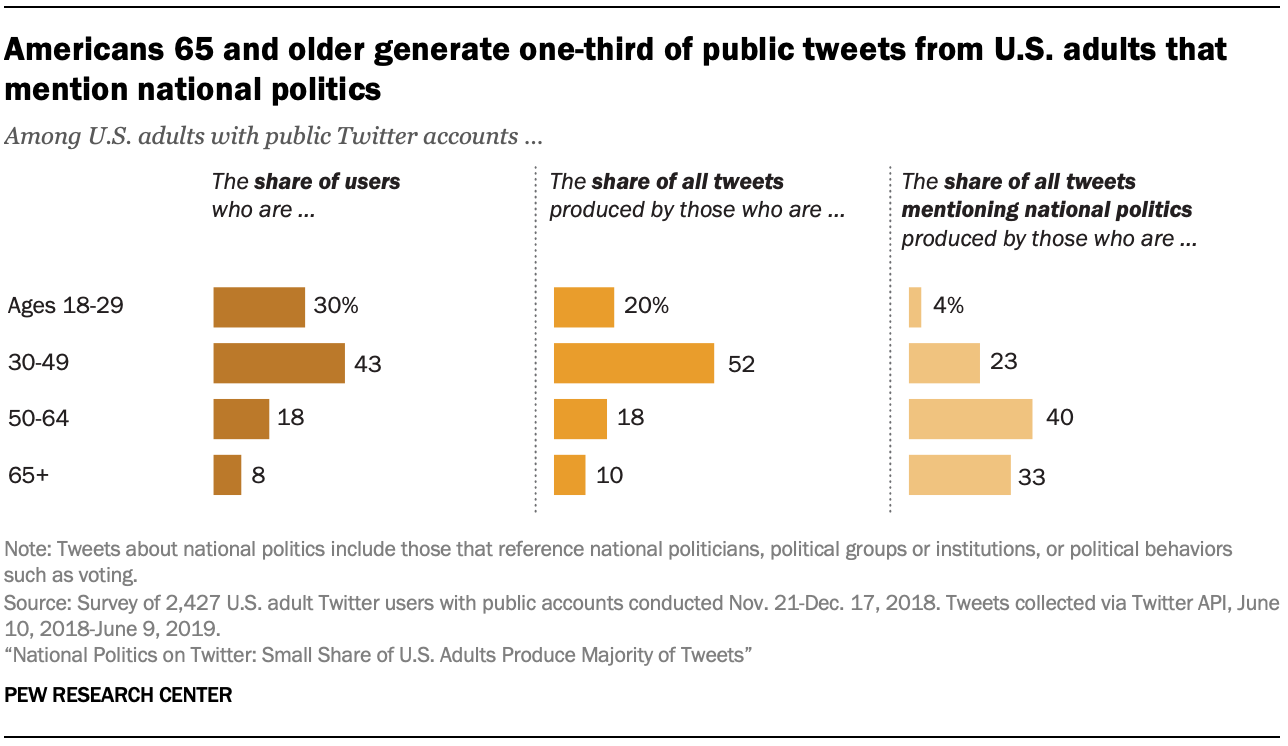

Older Americans produce sizable share of tweets by U.S. adults mentioning national politics

Reflecting the modest share of all Twitter users they represent, older adults on Twitter don’t produce a great deal of the total content. But this group is much more inclined to talk about national politics in their tweets than younger users. Those ages 65 and older produce just 10% of all tweets from U.S. adults, but these older Twitter users contribute 33% of tweets related to national politics. More broadly, those 50 and older produce 29% of all tweets but contribute 73% of tweets mentioning national politics. By contrast, 18- to 29-year-olds produce 20% of all public tweets from U.S. adults, but just 4% of political tweets.

In addition to these age-related differences, Republicans who describe themselves as conservative and Democrats who indicate that they are liberal are more likely to tweet about national politics than others in their parties. Researchers used an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (“very conservative”) to 10 (“very liberal”) to measure how individuals self-identified ideologically. Among Republicans and Republican leaners who identify as conservative (0-4) on the scale, 25% of tweets mention national politics. But just 9% of tweets from Republicans at the midpoint or liberal end of the scale (5-10) do the same.

Among Democrats and Democratic leaners, there is a similar pattern: 17% of tweets from Democrats who identify as liberal (6-10) on the scale mention national politics, compared with 5% among those who do not identify in this way (0-5).

The different types of Twitter users examined in this report

To compare the attitudes and behaviors of different types of Twitter users, researchers classified respondents to the survey into one of three categories based on how often they tweet in general, as well as whether they tweet about national politics.

Political tweeters are defined as those who tweeted at least five times over the study period, with a minimum of two of those tweets discussing national politics. About three-in-ten (31%) U.S. adults are in this group. Political tweeters are particularly likely to be Democrats: 67% of political tweeters identify as Democrats or lean toward the Democratic Party; 28% identify as Republicans or lean toward the GOP. The model used in this report estimates that 13% of all tweets produced by this group are political. Among those who say in the accompanying survey that they have tweeted about politics in the last 30 days, 78% meet our definition of a political tweeter based on their Twitter behavior. This group also contains some of the most active tweeters in the sample in terms of overall tweet volume.

Nonpolitical tweeters are defined as those who tweeted at least five times over the study period, but had no more than one tweet in that time that mentioned national politics. This group makes up 26% of U.S. adults on Twitter. Overall, 63% of nonpolitical tweeters identify as Democrats or lean toward the Democratic Party; 33% identify as Republicans or lean toward the GOP. Less than 1% of all tweets from this group are political in nature.

Infrequent tweeters are defined as those who tweeted fewer than five times in total over the year and includes those who did not tweet at all. Infrequent tweeters make up 43% of all U.S. adults on Twitter. Overall, 54% of infrequent tweeters identify as Democrats or lean toward the Democratic Party; 42% identify as Republicans or lean toward the GOP. This group accounts for fewer than 1% of all tweets produced by U.S. adults; 6% of their tweets are classified as political.

Political tweeters report visiting the site with great regularity: 73% of this group says they use the site at least once a day. The other two groups contain a smaller share of regular visitors to the site: 48% of nonpolitical tweeters and 33% of infrequent tweeters say that they use the site on a daily basis.

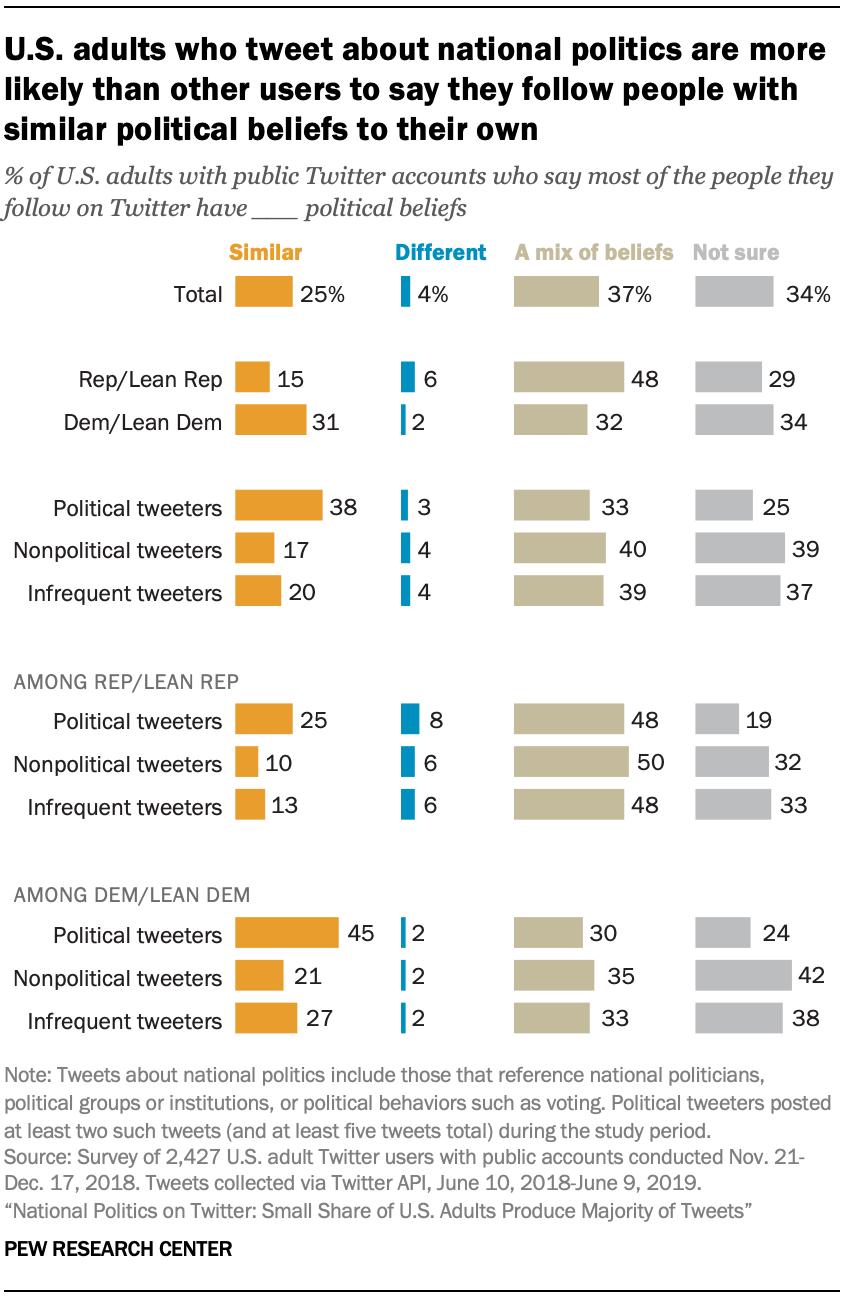

Political tweeters are more likely to follow other people who share their political views

Most

U.S. adults on Twitter report that they follow people with a mix of

political views (37%) or that they don’t know the political views of the

people they follow (34%). A quarter (25%) say most of the people they

follow on Twitter hold similar political views to their own, while just

4% say that most of the people they follow have political views that are

different from theirs.

Most

U.S. adults on Twitter report that they follow people with a mix of

political views (37%) or that they don’t know the political views of the

people they follow (34%). A quarter (25%) say most of the people they

follow on Twitter hold similar political views to their own, while just

4% say that most of the people they follow have political views that are

different from theirs. The above relationship – in which a majority of users follow either a mix of people with different beliefs or say they aren’t sure of the political views of the people they follow – holds for the three types of Twitter users identified in this analysis (political tweeters, nonpolitical tweeters and infrequent tweeters). Still, the share of Twitter users who say they follow people with political views similar to their own is much higher among those who tweet about national politics (38%) than it is among nonpolitical tweeters (17%) and those who tweet infrequently (20%). In part, this dynamic is driven by the fact that nonpolitical tweeters (39%) and those who tweet infrequently (37%) are more likely than political tweeters (25%) to say they don’t know the political views of the people they follow.

Democrats and Democratic leaners on Twitter are about twice as likely as Republican and Republican-leaning users to say that most of the people they follow hold similar political views to theirs (31% vs. 15%). A previous Pew Research Center report found that Democrats make up a larger share of all Twitter users than of the general public overall.

Both Republicans and Democrats who tweet about national politics are more likely to say they follow people with similar political views than those who don’t tweet about politics. However, reflecting differences between partisans among all Twitter users generally, a larger share of Democrats (45%) than Republicans (25%) who tweet about national politics say they mostly follow people with political views that are similar to their own.

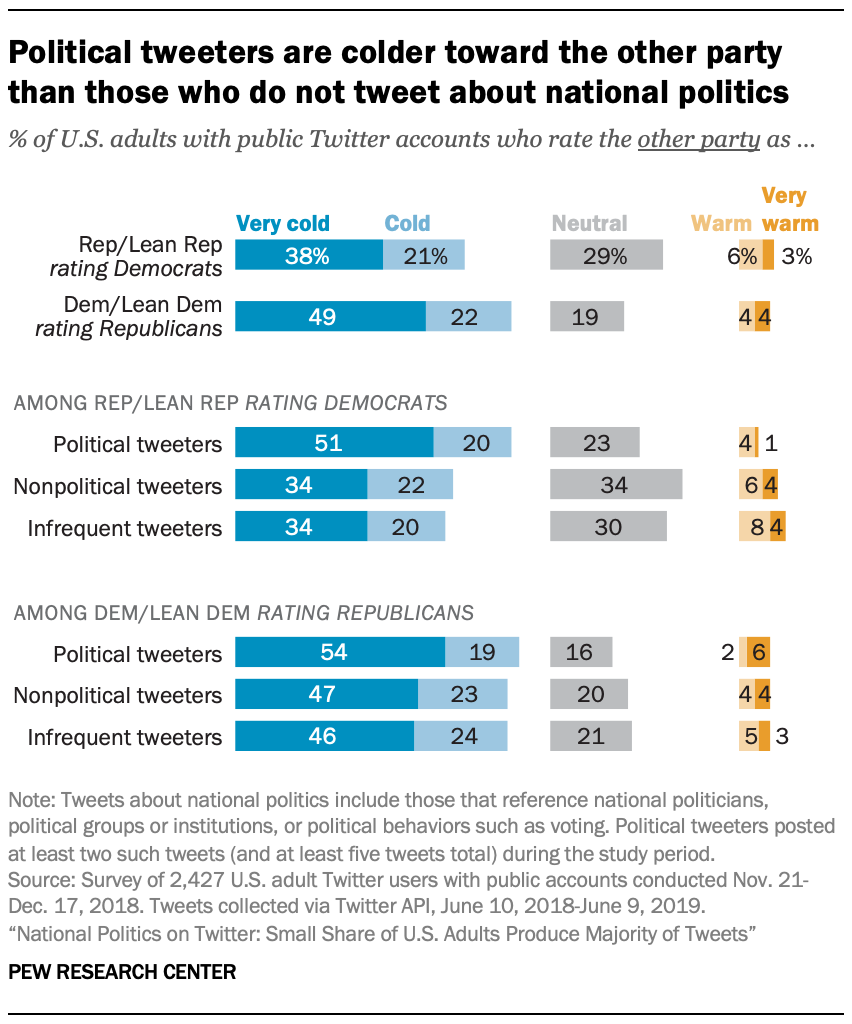

Political tweeters have ‘colder’ views of members of the other party

Partisans

who tweet about national politics are more likely than those who do not

to give members of the other party a “very cold” rating (a rating of

less than 25 degrees on a 0-100 “feeling thermometer” scale).

Partisans

who tweet about national politics are more likely than those who do not

to give members of the other party a “very cold” rating (a rating of

less than 25 degrees on a 0-100 “feeling thermometer” scale). This phenomenon is particularly prominent among Republicans: 51% of Republicans and Republican leaners who tweet about national politics give a very cold rating to Democrats – significantly higher than the shares of Republicans who don’t tweet about politics.

Among Democrats and Democratic leaners who tweet about national politics, 54% give a very cold rating to Republicans. Somewhat smaller shares of Democrats who don’t tweet about national politics give an equally cold rating for members of the other party.

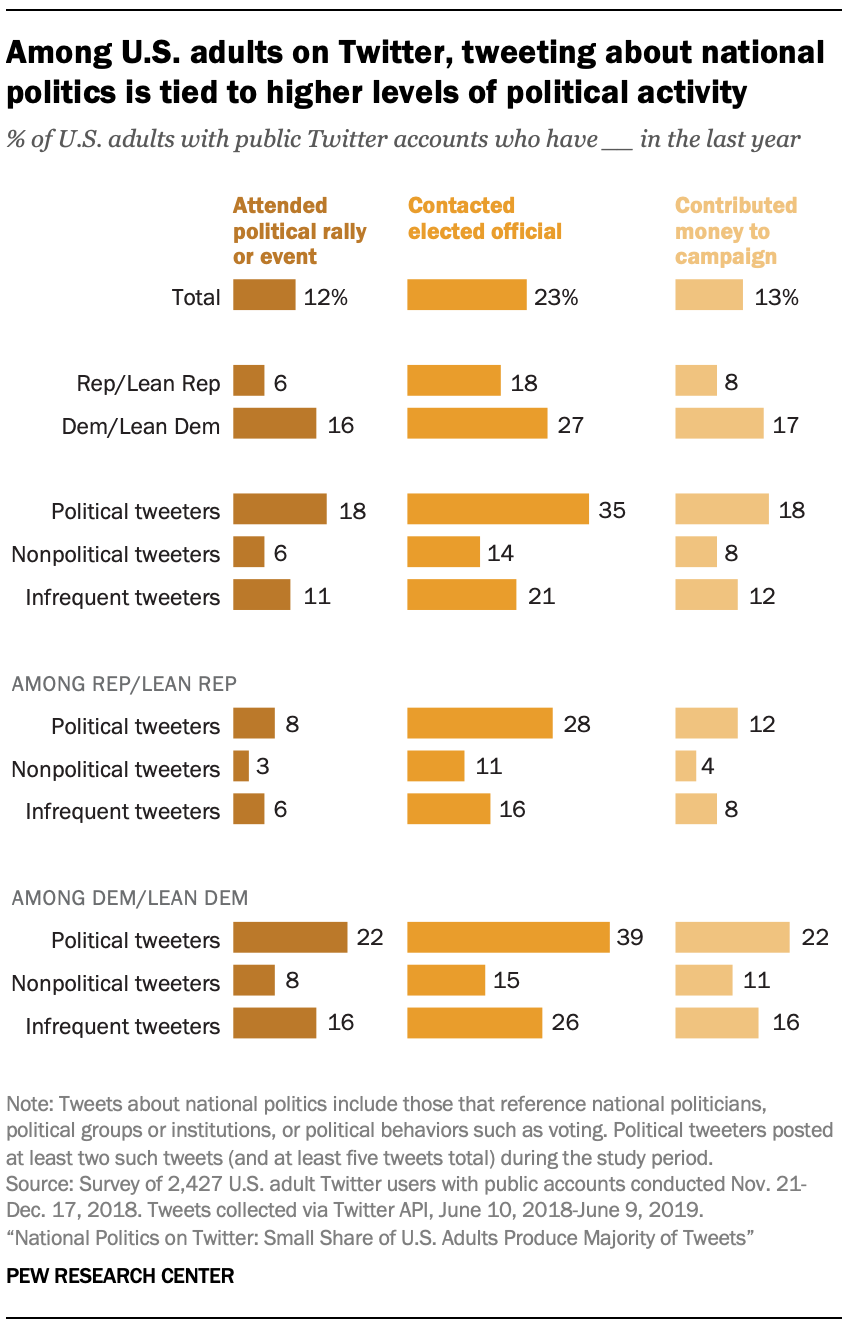

Greater levels of political activity and engagement among those who tweet about national politics

Those

who tweet about national politics are more likely than those who do not

to report engaging in a range of behaviors related to political

activity and engagement.

Those

who tweet about national politics are more likely than those who do not

to report engaging in a range of behaviors related to political

activity and engagement. For example, 35% of national political tweeters say they have contacted an elected official within the last year, compared with 14% of nonpolitical tweeters and 21% of infrequent tweeters. Political tweeters are also more likely than the other two groups to say they have attended a political rally or protest or contributed money to a candidate running for office in the last year.

Within both political parties, national political tweeters are more likely to report engaging in political activity than nonpolitical tweeters.

Larger shares of Democratic political tweeters than Republican political tweeters say they participated in each of the three types of political behavior measured in the survey. This pattern is consistent with surveys of the general public conducted during the 2018 midterm election campaign, which found higher levels of political engagement among Democrats than Republicans.

National political tweeters also are somewhat more likely than other Twitter users to say they regularly follow the news. About two-thirds of national political tweeters (65%) say they follow the news closely whether or not something important is happening, slightly larger than the shares of infrequent tweeters (59%) and nonpolitical tweeters (53%) who say the same.

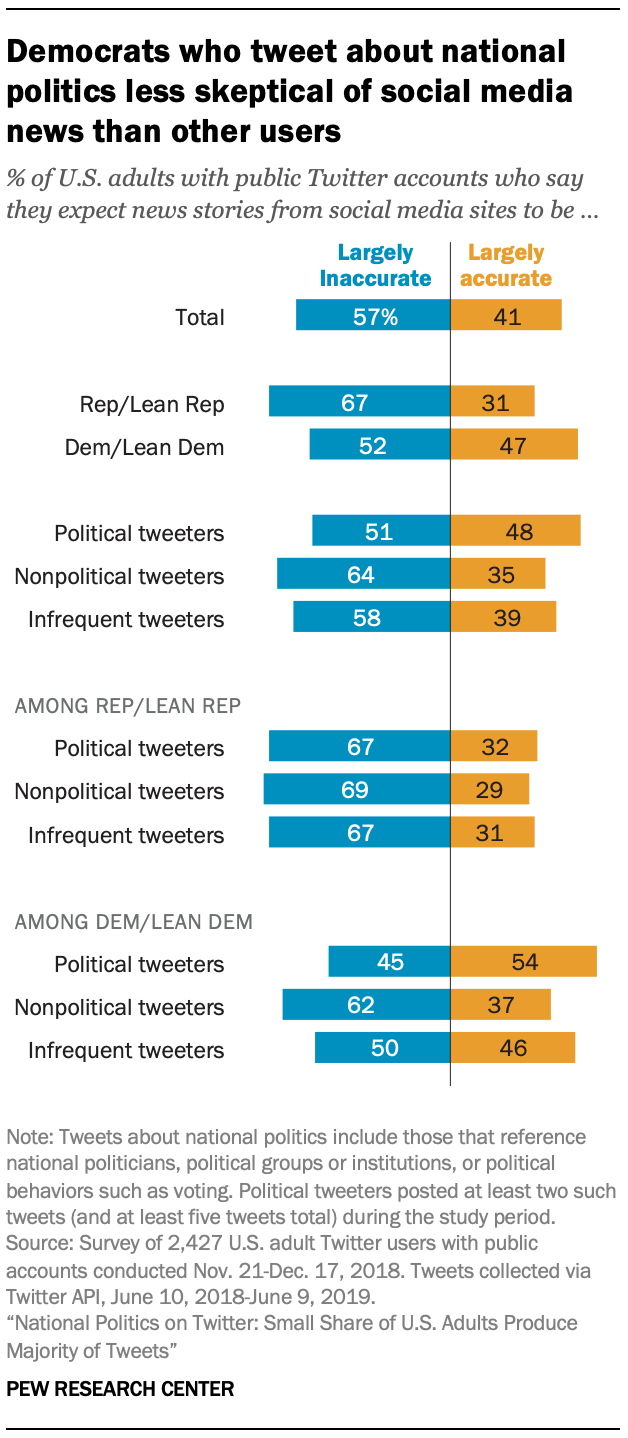

U.S. adults on Twitter skeptical about the accuracy of news from social media sites

Most

Twitter users (57%) say they expect the news they see on social media

sites to be largely inaccurate; 41% expect the news they see on social

media to be largely accurate.

Most

Twitter users (57%) say they expect the news they see on social media

sites to be largely inaccurate; 41% expect the news they see on social

media to be largely accurate. However, political tweeters are more evenly divided: 48% expect the news they see on social media to be largely accurate, while a comparable share (51%) expects it to be largely inaccurate. Other Twitter users with public accounts are more skeptical: 64% of nonpolitical tweeters and 58% of infrequent tweeters say they approach news stories from social media sites with the expectation that they will be largely inaccurate.

Differences on this question are driven largely by views among Democrats.

Democrats and Democratic leaners who tweet about politics are more likely than Democrats who don’t tweet about politics and Democrats who are infrequent tweeters to say they expect news stories from social media sites to be largely accurate (54% compared with 37% and 46%, respectively).

However, there is no comparable relationship among Republicans and Republican leaners. About two-thirds of Republicans across all three groups of Twitter users say they expect news stories from social media sites to be largely inaccurate.

Among the general public, Republicans are far more likely than Democrats to express distrust in news organizations and rate the impact of the national news media on the country negatively.

The most prolific political tweeters have behaviors and attitudes distinct from other U.S. adults on Twitter

As a group, political tweeters differ in numerous ways from those who tweet about nonpolitical topics and from those who rarely tweet at all. It’s also the case that there are meaningful differences within the group of users who tweet about national politics. The most prolific political tweeters (defined as those who tweeted at least 10 times and mentioned national politics in at least 25% of those tweets) stand out even from other political tweeters (whose political tweets make up a smaller share of their total output). Prolific political tweeters make up just 6% of all Twitter users but generate 20% of all tweets and 73% of tweets mentioning national politics.

Compared with other political tweeters, even larger shares of these highly prolific users say they largely follow others on Twitter who share their political views (51%) and that they follow the news closely whether or not something important is happening (92%). And this group is highly active in more traditional forms of political activity: 57% have contacted an elected official in the last year, while 38% have made a political donation and 34% have attended a rally.