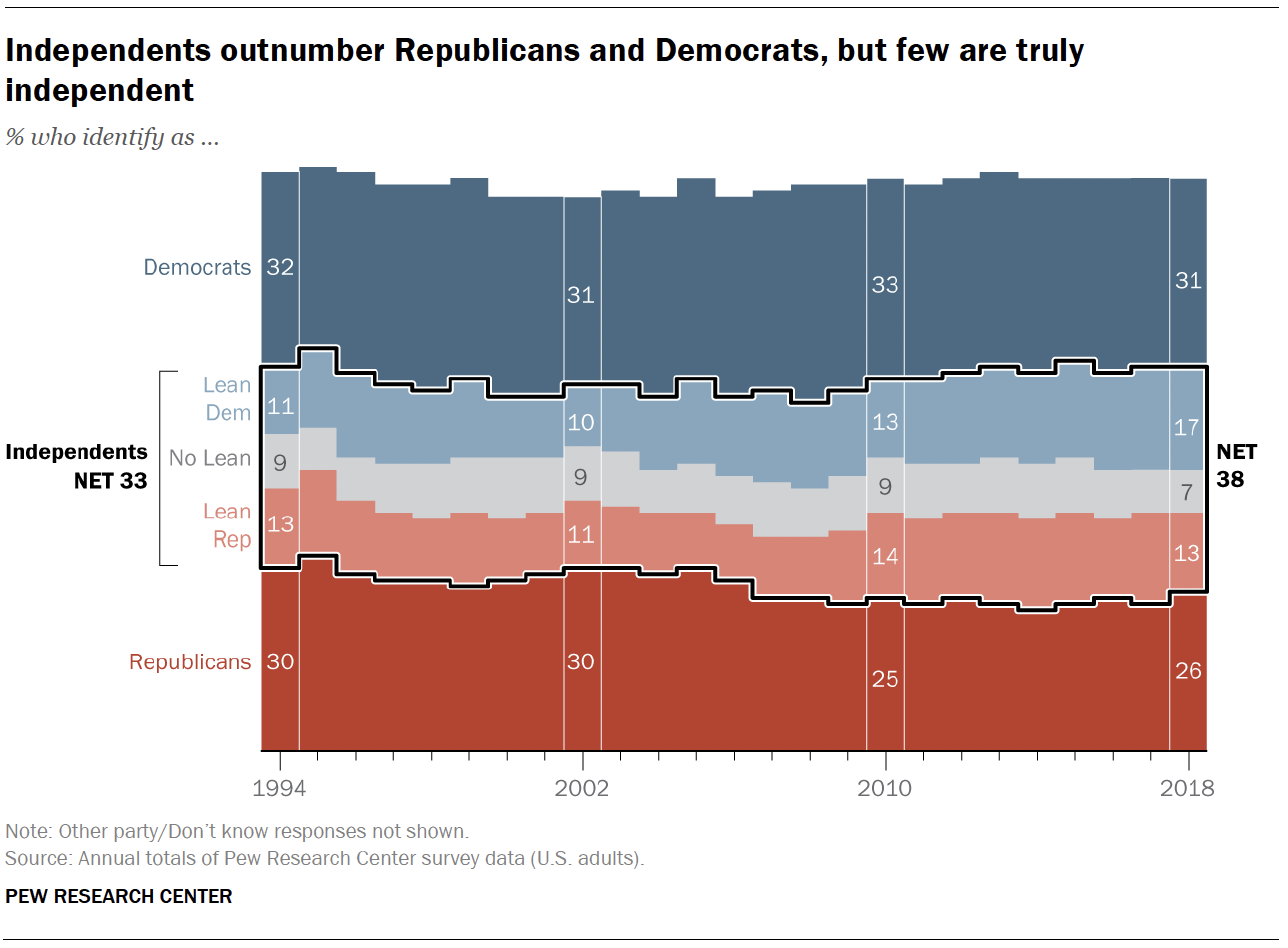

Most ‘lean’ toward a party; ‘true’ independents tend to avoid politics

Independents

often are portrayed as political free agents with the potential to

alleviate the nation’s rigid partisan divisions. Yet the reality is that

most independents are not all that “independent” politically. And the

small share of Americans who are truly independent – less than 10% of

the public has no partisan leaning – stand out for their low level of

interest in politics.

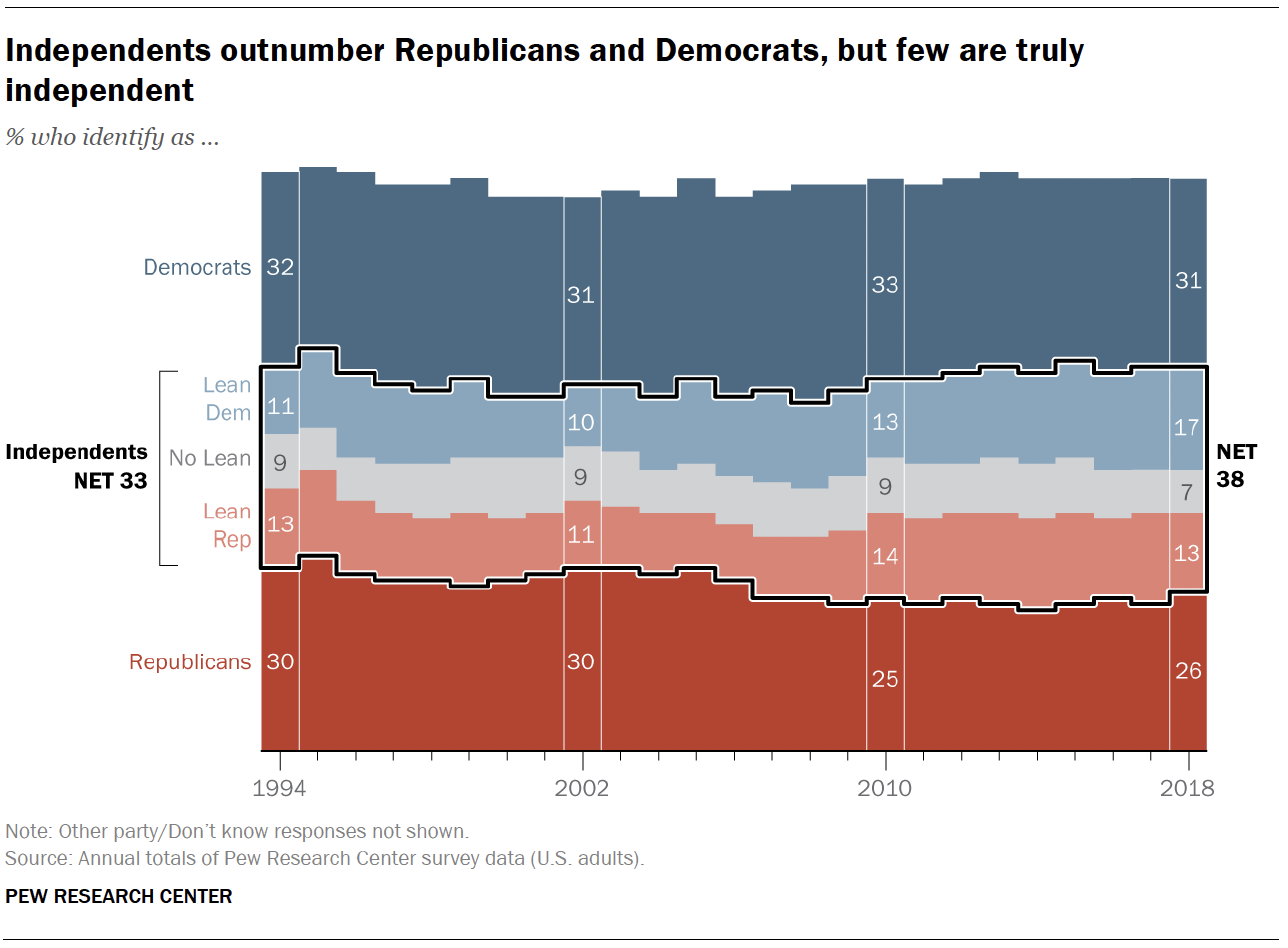

Among the public overall, 38% describe

themselves as independents, while 31% are Democrats and 26% call

themselves Republicans, according to Pew Research Center surveys

conducted in 2018. These shares have changed only modestly in recent

years, but the proportion of independents is higher than it was from

2000-2008, when no more than about a third of the public identified as

independents. (For more on partisan identification over time, see the

2018 report “

Wide Gender Gap, Growing Educational Divide in Voters’ Party Identification.”)

An

overwhelming majority of independents (81%) continue to “lean” toward

either the Republican Party or the Democratic Party. Among the public

overall, 17% are Democratic-leaning independents, while 13% lean toward

the Republican Party. Just 7% of Americans decline to lean toward a

party, a share that has changed little in recent years. This is a

long-standing dynamic that has been the subject of past analyses, both

by

Pew Research Center and

others.

In

their political attitudes and views of most issues, independents who

lean toward a party are in general agreement with those who affiliate

with the same party. For example, Republican-leaning independents are

less supportive of Donald Trump than are Republican identifiers. Still,

about 70% of GOP leaners approved of his job performance during his

first two years in office. Democratic leaners, like Democrats,

overwhelmingly disapprove of the president.

There

are some issues on which partisan leaners – especially those who lean

toward the GOP – differ substantially from partisans. While a narrow

majority of Republicans (54%) opposed same-sex-marriage in 2017, nearly

six-in-ten Republican-leaning independents (58%) favored allowing gays

and lesbians to marry legally.

Yet independents who lean toward

one of the two parties have a strong partisan imprint. Majorities of

Republican and Democratic leaners have a favorable opinion of their own

party, and they are almost as likely as Republican and Democratic

identifiers to have an unfavorable opinion of the opposing party.

Independents

stand out from partisans in several important ways. They less

politically engaged than Republicans or Democrats – and this is

especially the case among independents who do not lean to a party.

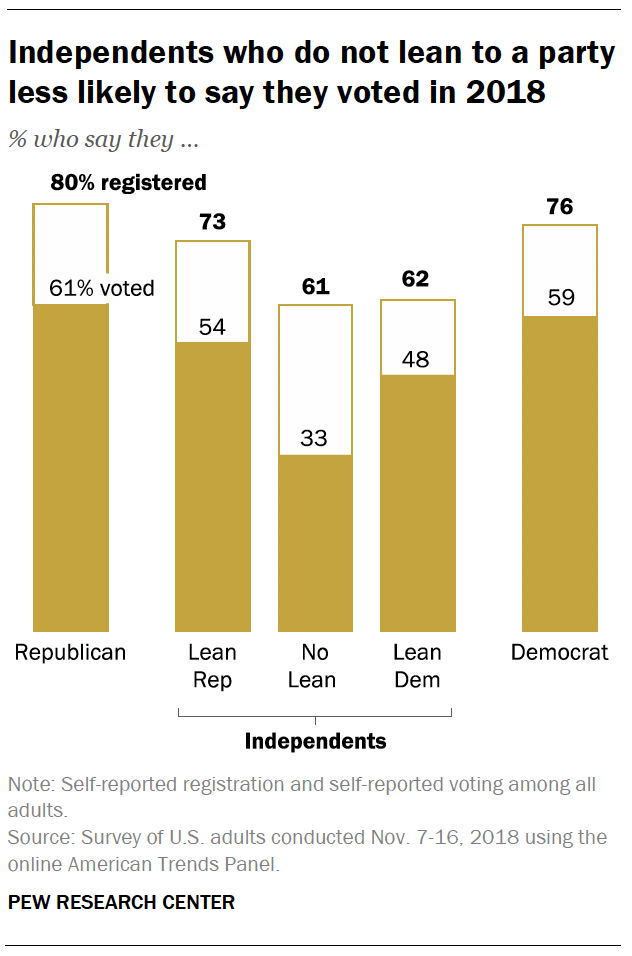

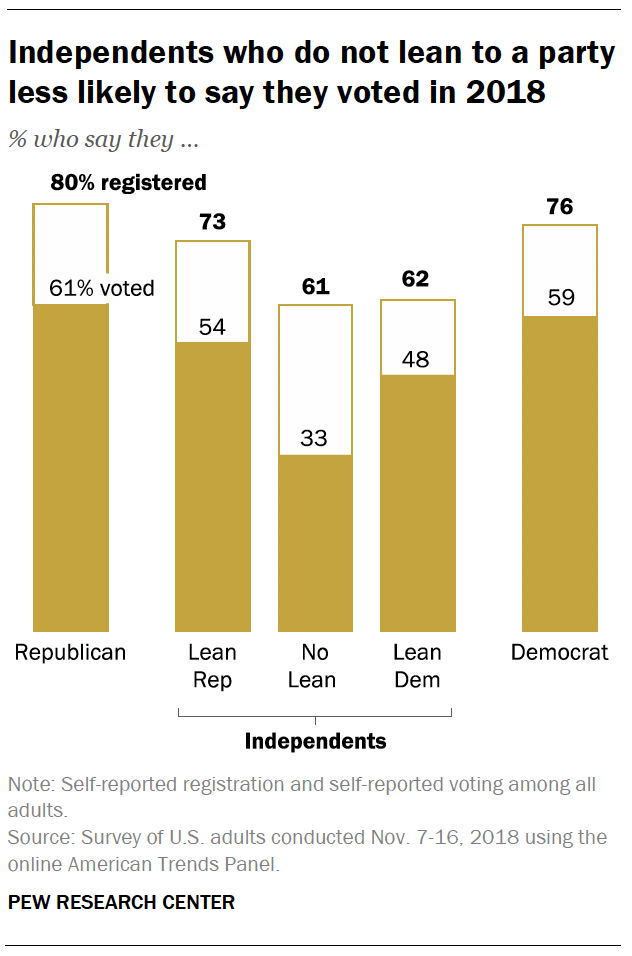

In

a survey conducted last fall, shortly after the midterm elections,

partisan leaners were less likely than partisans to say they registered

to vote and voted in the congressional elections. About half of

Democratic-leaning independents (48%) said they voted, compared with 59%

of Democrats. The differences were comparable between GOP leaners (54%

said they voted) and Republicans (61%).

Those who do not lean

toward a party – a group that consistently expresses less interest in

politics than partisan leaners – were less likely to say they had

registered to vote and much less likely to say they voted. In fact, just

a third said they voted in the midterms.

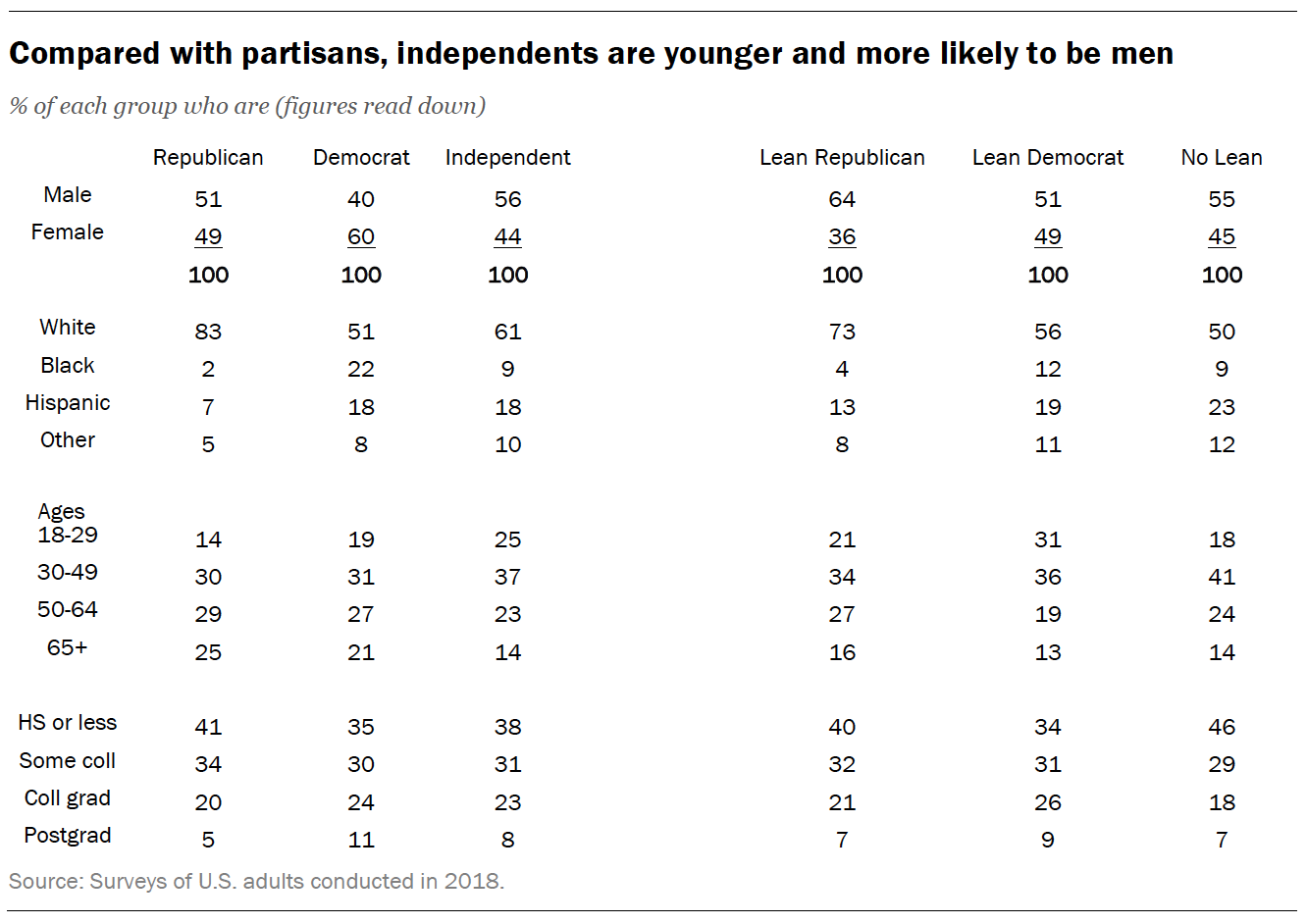

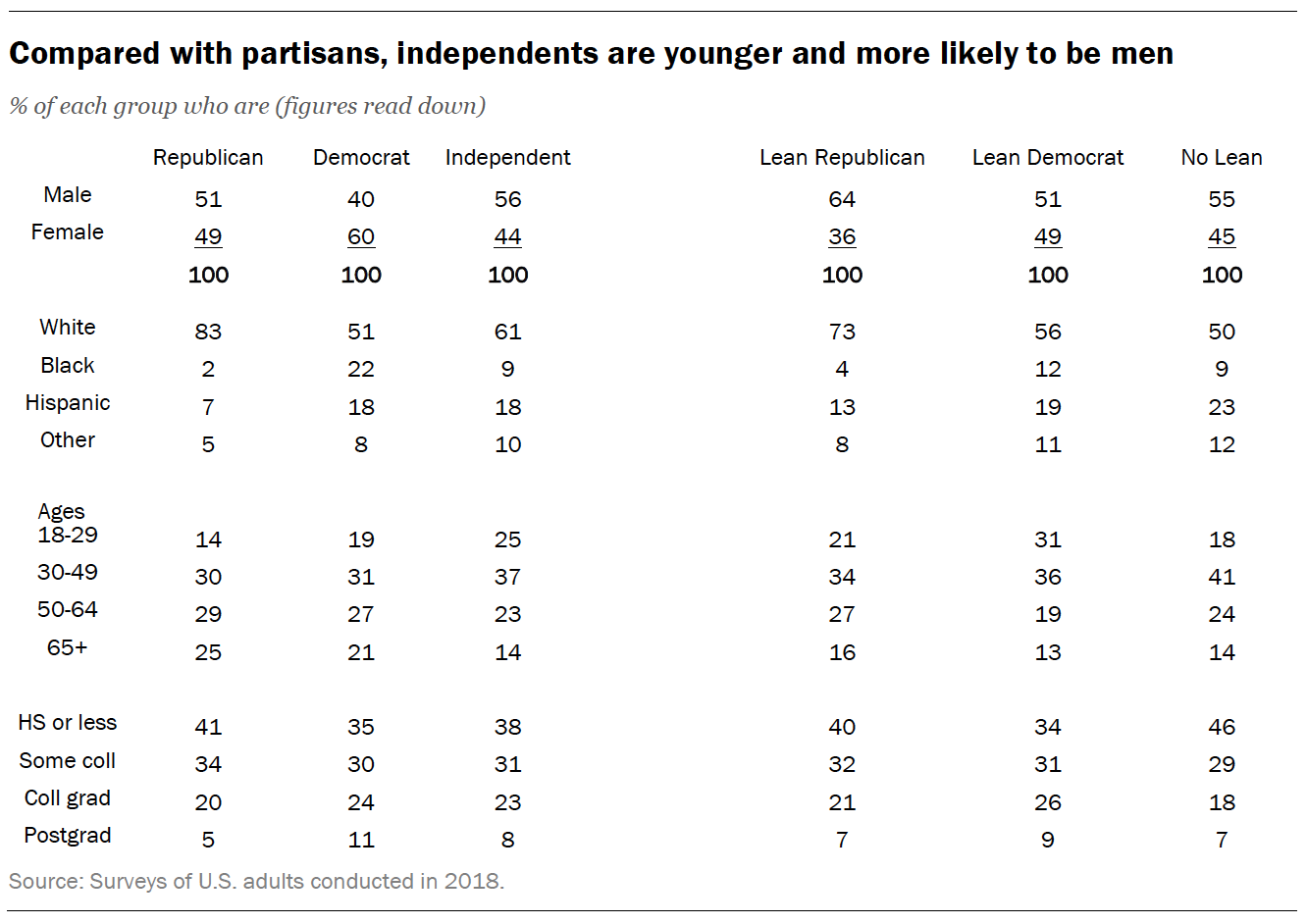

In addition,

independents differ demographically from partisans. Men constitute a

majority (56%) of independents. That is higher than the share of men

among Republican identifiers (51% are men) and much higher than the

share of men among Democrats (just 40%).

Among independents, men

make up a sizable share (64%) of Republican leaners and a smaller

majority (55%) of independents who do not lean. Democratic leaners

include roughly equal shares of men (51%) and women (49%).

Independents

also are younger on average than are partisans. Fewer than half of

independents (37%) are ages 50 and older; among those who identify as

Democrats, 48% are 50 and older, as are a majority (54%) of those who

identify as Republicans.

Democratic-leaning independents are

younger than other independents or partisans. Nearly a third (31%) are

younger than 30, compared with 21% of Republican-leaning independents

and just 19% and 14%, respectively, among those who identify as

Democrats and Republicans.

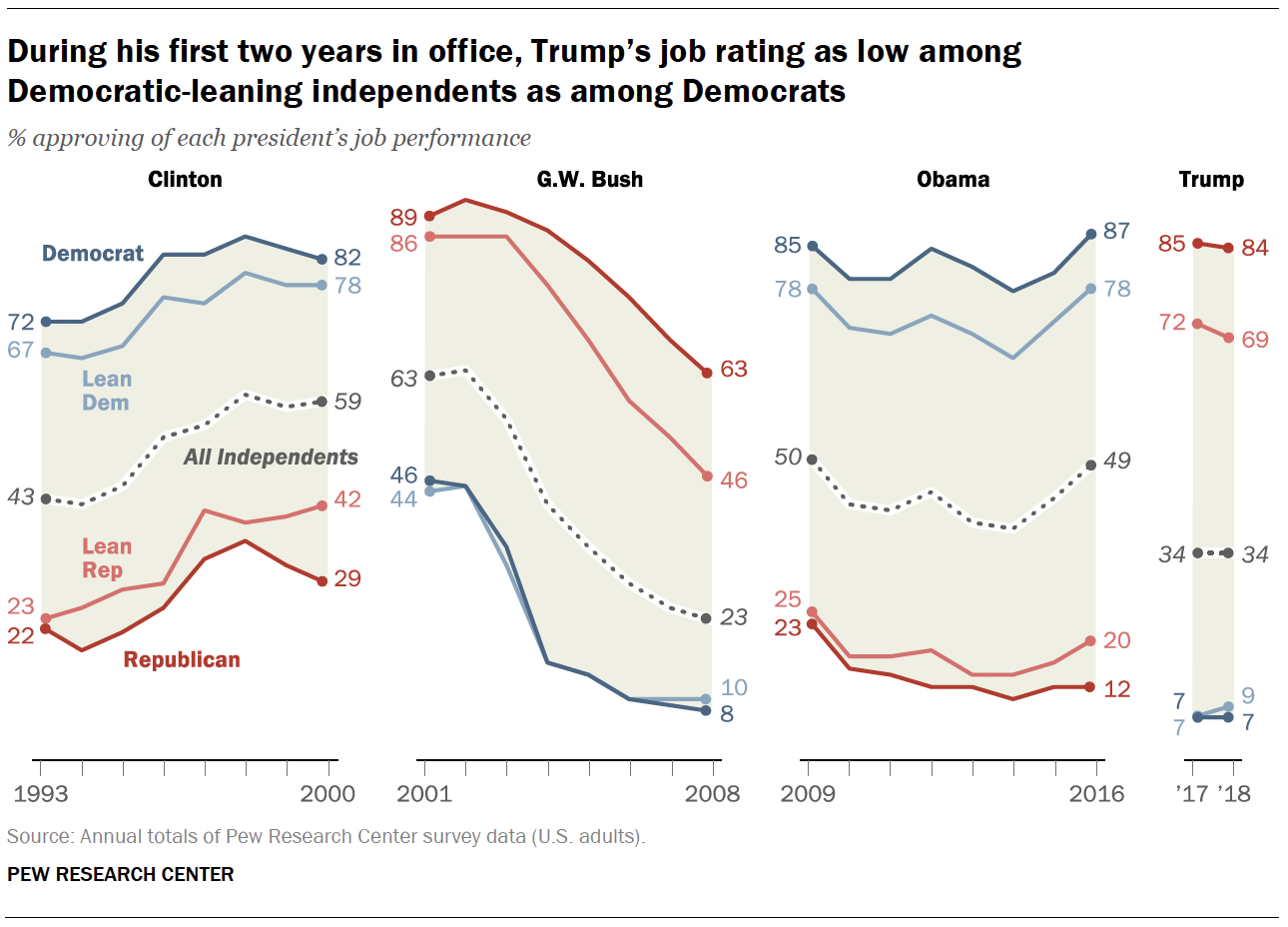

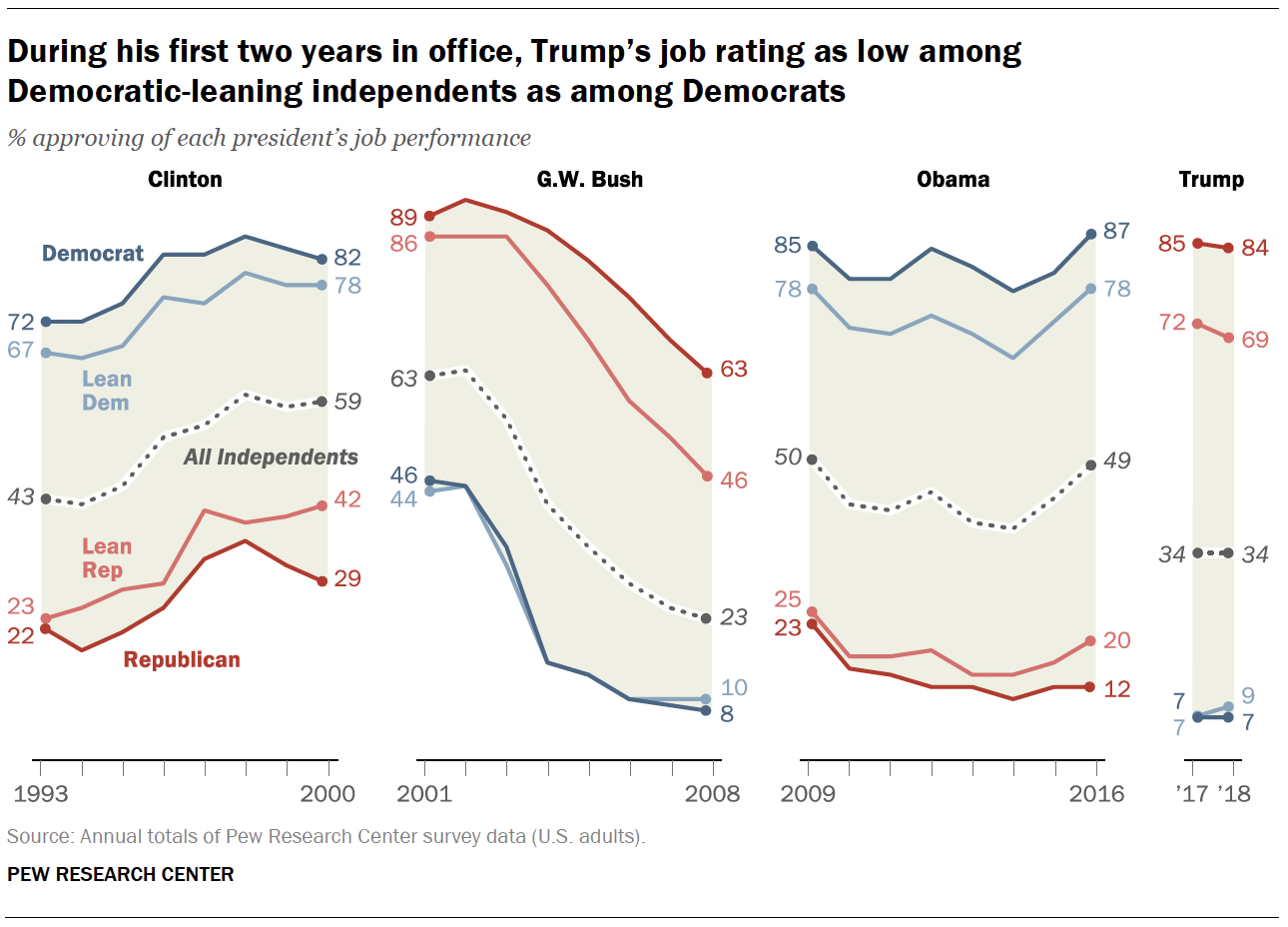

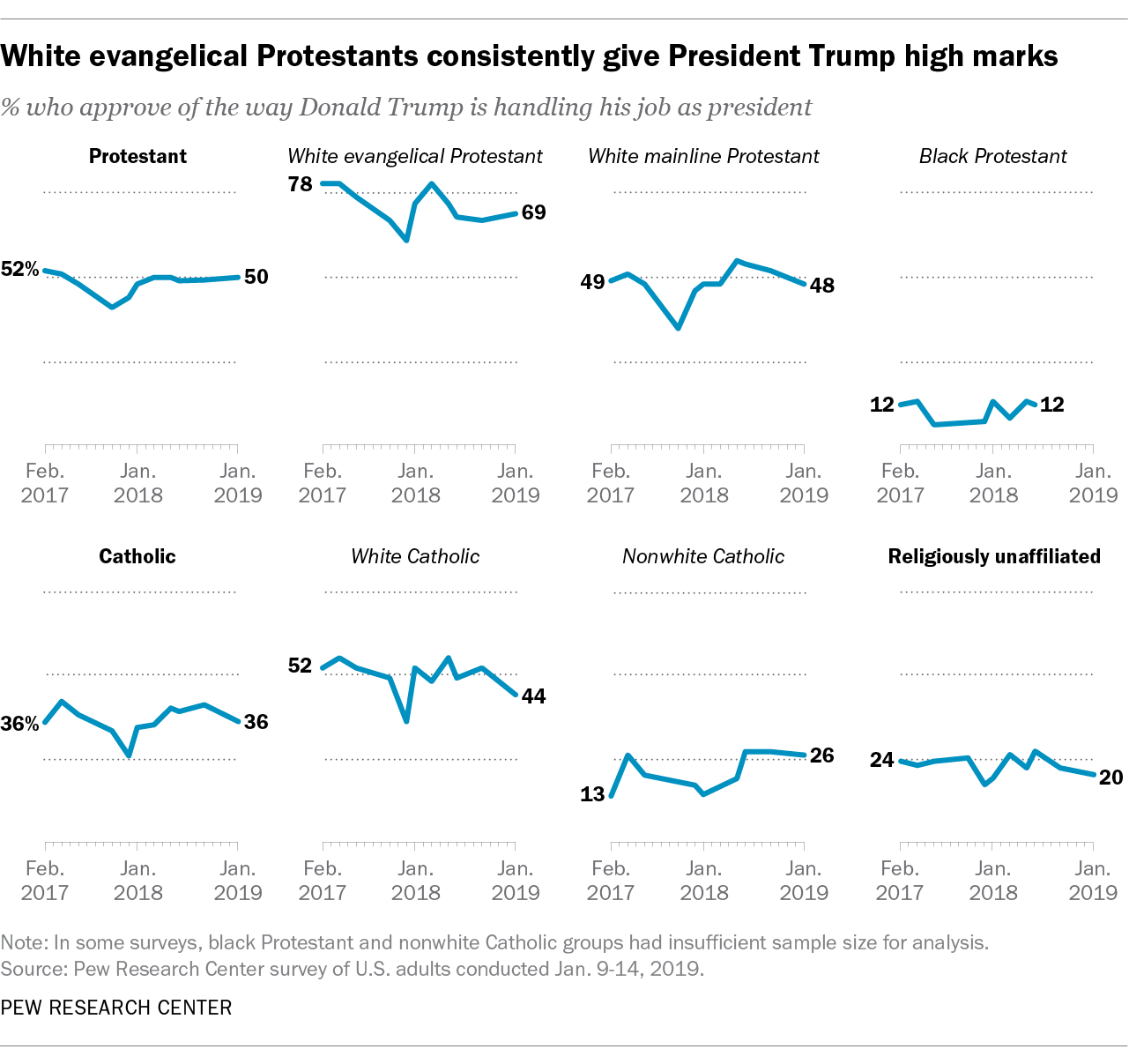

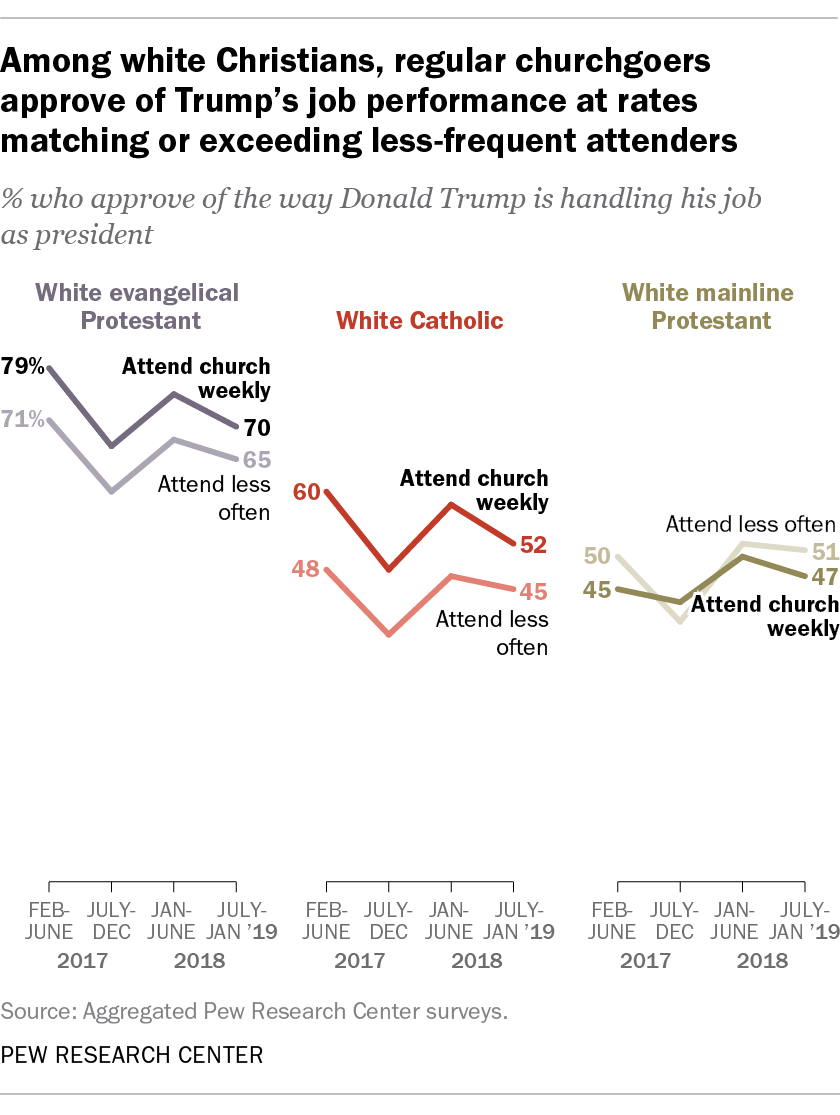

Trump divides partisans and partisan leaners alike

As Pew Research Center reported last year,

Donald Trump’s job approval rating during the early stage of his

presidency is more polarized along partisan lines than any president in

the past six decades. In addition, Trump’s rating has been more stable

than prior presidents.

During his first two years in office,

Trump’s job rating among members of his own party was relatively high

compared with recent presidents. In 2017, 85% of those who identify as

Republicans approved of Trump’s job performance, based on an average of

Pew Research Center surveys. His job rating among Republicans was about

as high (84%) in 2018. Trump’s early job rating among members of the

opposing party (7%) was much lower than those of three prior presidents

(Barack Obama, George W. Bush and Bill Clinton).

Trump’s job

rating among independents for his first two years in office also was

lower than his recent predecessors; his average job rating among

independents was 34% in both 2017 and 2018. Obama’s average rating was

50% during his first year (2009); it fell to 42% in his second year.

Trump’s

early rating among independents is closest to Clinton’s, whose job

approval averaged about 42% during his first two years in office. Bush,

whose overall job rating approached 90% in his first year following the

9/11 terrorist attacks, had approval ratings above 60% among

independents in his first two years.

Trump’s job rating among

independents, like his overall rating, breaks down along partisan lines.

His rating among GOP-leaning independents (72% in 2017, 69% in 2018)

was not markedly different from Obama’s and Clinton’s ratings among

Democratic-leaning independents during their first two years in office

(though much lower than Bush’s among Republican leaners).

Yet

Trump’s rating among independents who lean to the opposing party – like

his rating among members of the opposing party – was much lower than

recent presidents’. In fact, his rating among Democratic-leaning

independents during his first two years was about as low as his rating

among Democrats (7% in 2017, 9% in 2018).

Trump’s rating also

was low among independents who have no partisan leanings. Only about

quarter of non-leaners approved of Trump’s job performance during his

first two years, while about six-in-ten (58%) disapproved.

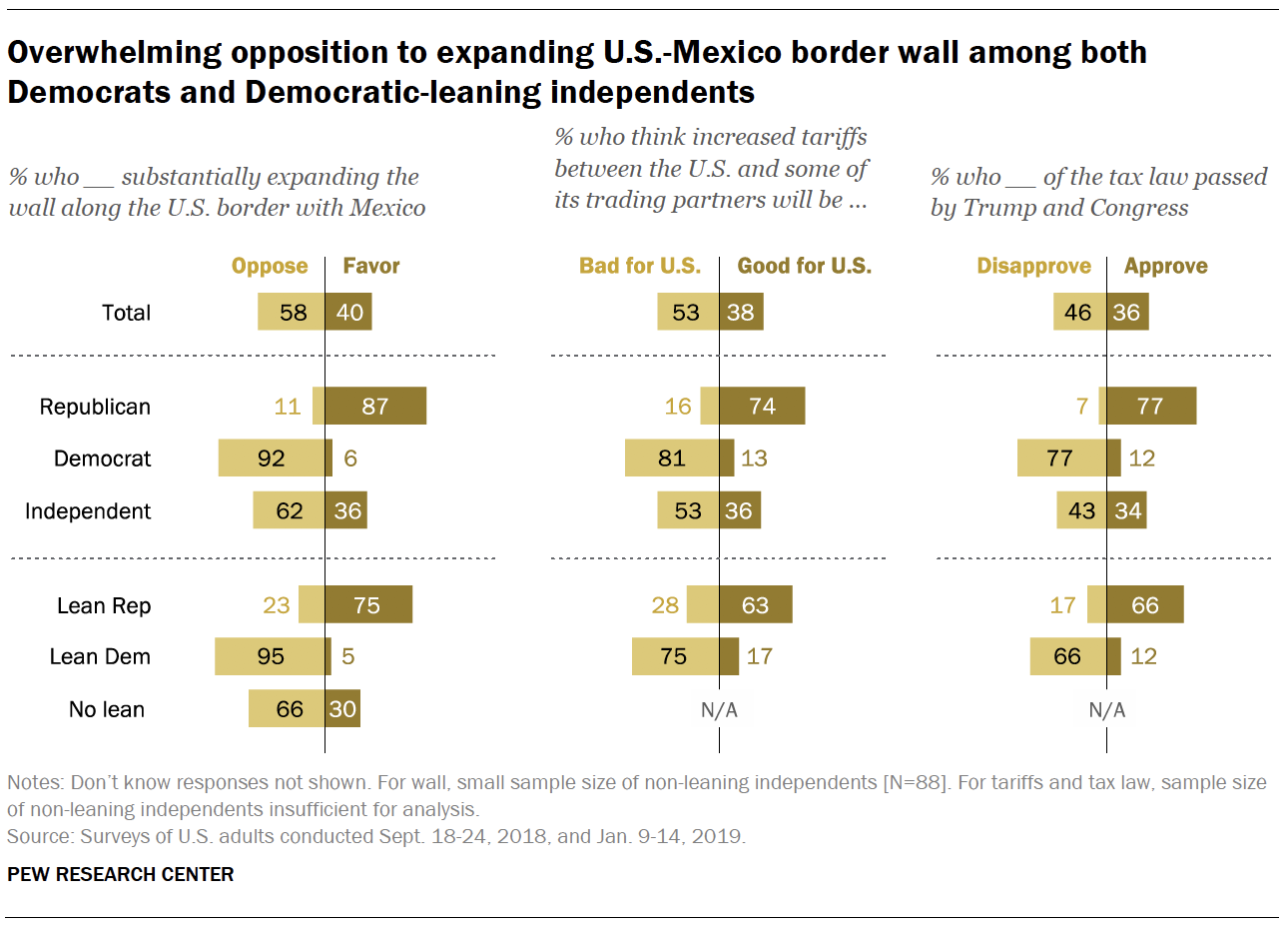

Independents’ views of U.S.-Mexico border wall, other key issues

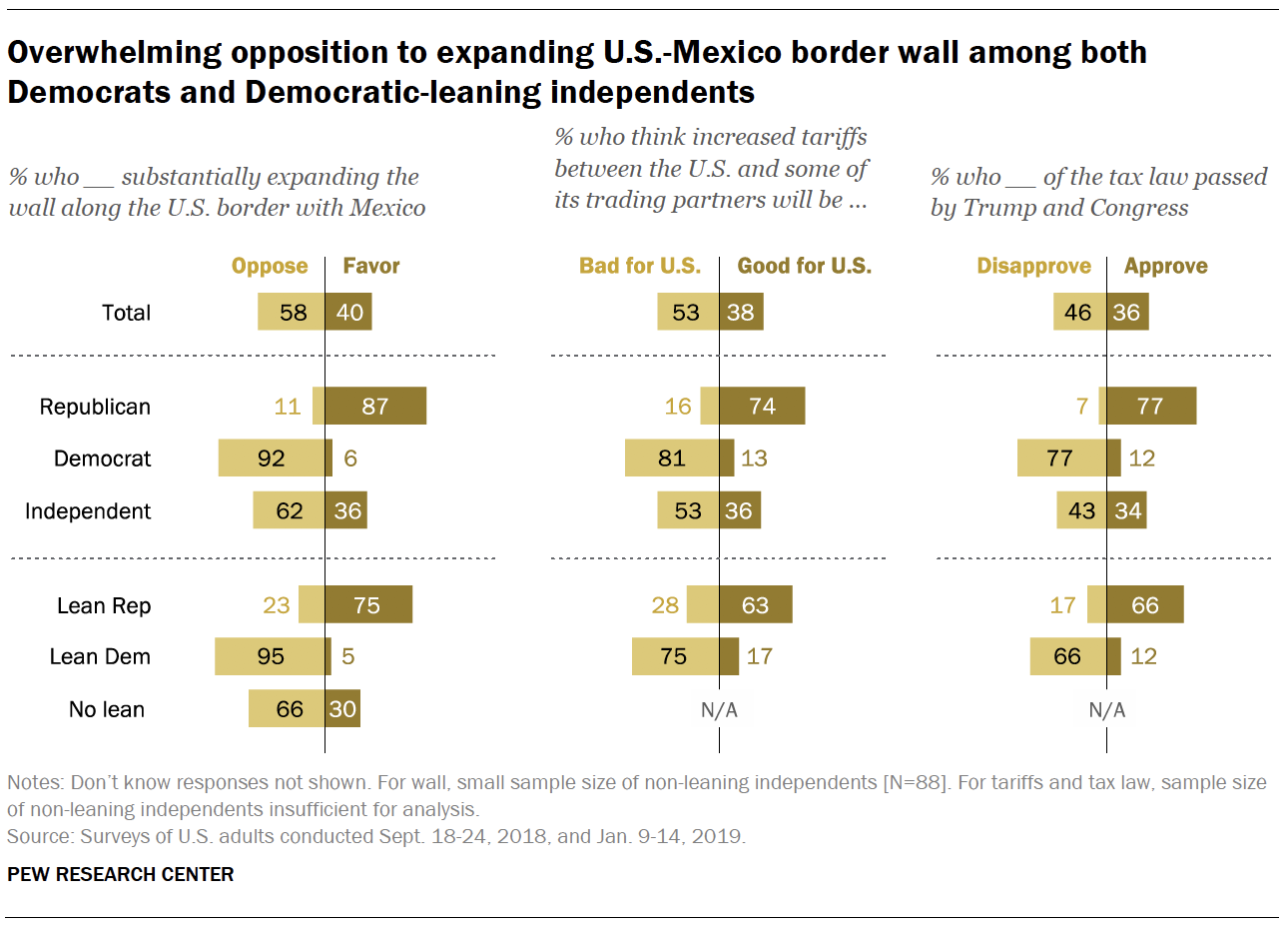

On

most issues, independents’ attitudes mirror the views of the overall

public. Independents who lean toward a party are usually on the same

side as those who identify with the same party, but the level of

agreement between leaners and partisans varies depending on the issue.

By

a wide margin (62% to 36%), independents oppose Trump’s signature

policy proposal, an expansion of the U.S.-Mexico border wall.

Democratic-leaning independents overwhelmingly oppose the border wall

(95% disapprove), as do Democratic identifiers (92%).

Republican-leaning

independents favor expanding the border wall, though by a smaller

margin than Republicans identifiers. GOP leaners favor substantially

expanding the wall along the U.S.-Mexico border by roughly three-to-one

(75% to 23%). Among those who affiliate with the Republican Party, the

margin is nearly eight-to-one (87% to 11%).

Independents

also have a negative view of increased tariffs between the U.S. and its

trading partners (53% say they will be bad for the U.S., 36% good for

the U.S.). Independents’ views on the 2017 tax bill are more divided:

34% approve of the tax law and 43% disapprove.

As with the

border wall, Democratic-leaning independents are more likely to view

increased tariffs negatively (75% say they will be bad for the U.S.)

than Republican-leaning independents are to view them positively (66%

say they will be good). On taxes, two-thirds of GOP leaners approve of

the tax law, while an identical share of Democratic leaners disapprove.

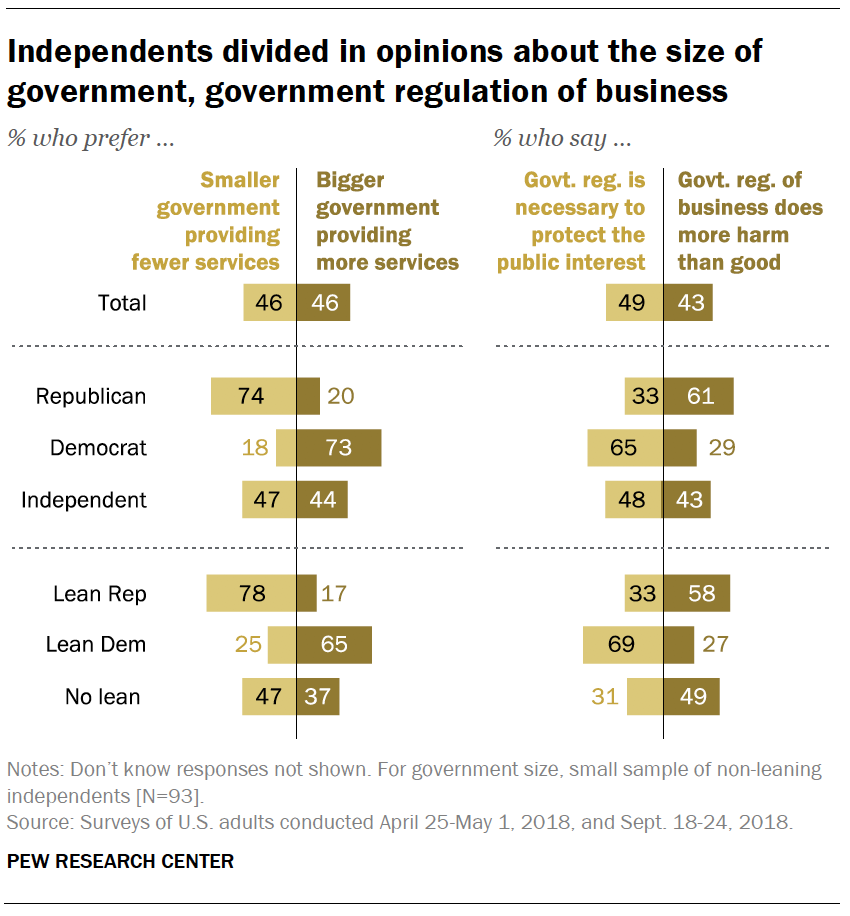

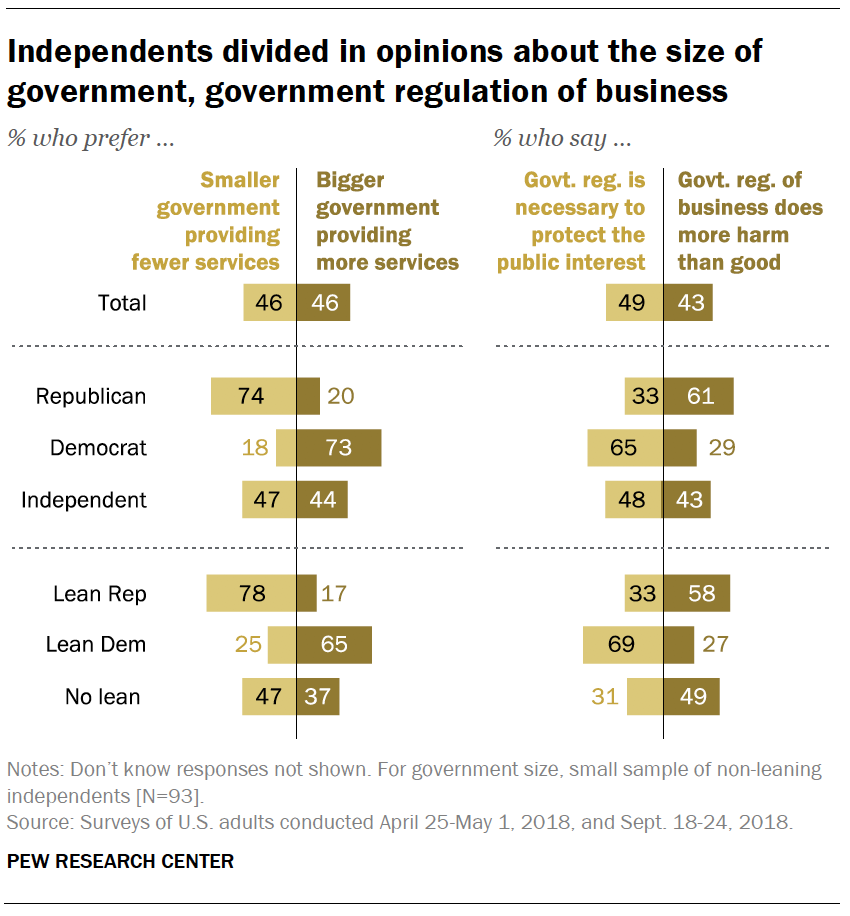

Overall,

independents are divided in preferences about the size of government

and views about government regulation of business.

Republican-leaning

independents largely prefer a smaller government providing fewer

services; 78% favor smaller government, compared with just 17% who favor

bigger government with more services.

The views of GOP leaners

are nearly identical to the opinions of those who affiliate with the GOP

(74% prefer smaller government). Like Democrats, most

Democratic-leaning independents prefer bigger government.

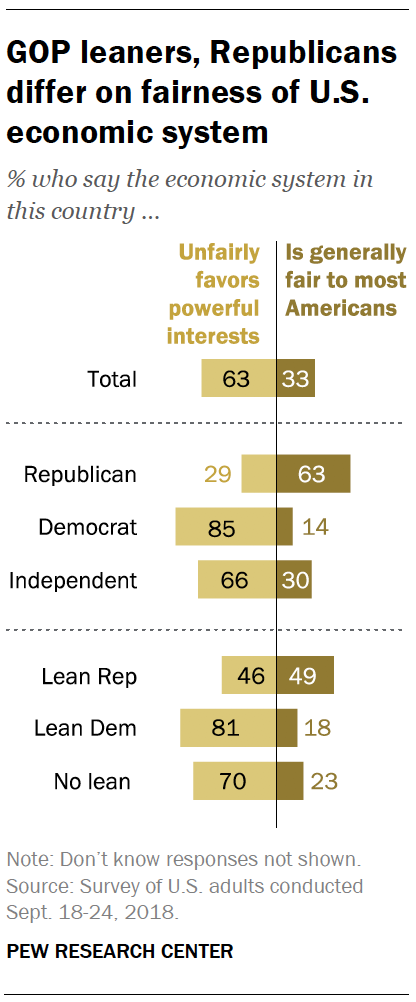

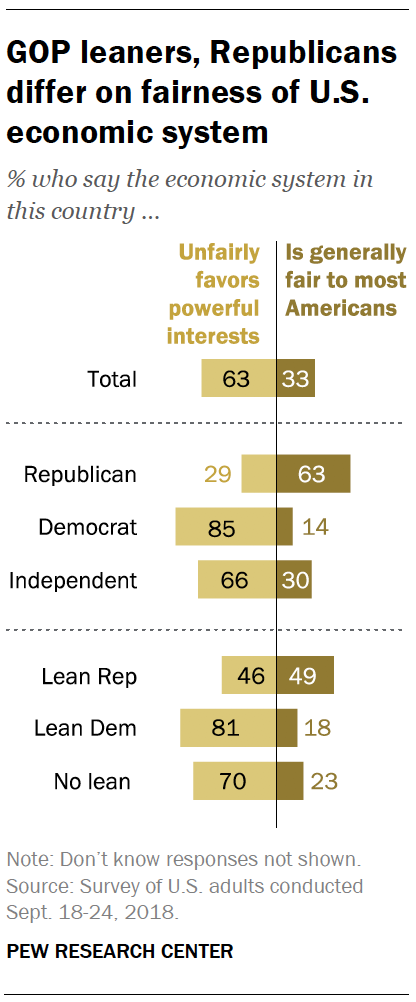

Democrats

and Democratic leaners are in sync in opinions about whether the

nation’s economic system is generally fair. But there are sharper

differences in the views of Republicans and GOP leaners.

A 63%

majority of those who identify as Republicans say the U.S. economic

system is fair to most Americans; fewer than half as many (29%) say the

system unfairly favors powerful interests. GOP leaners are divided: 49%

say the system is generally fair, while nearly as many (46%) say it

unfairly favors powerful interests.

Large majorities of both

Democrats (85%) and Democratic leaners (81%) say the U.S. economic

system unfairly favors powerful interests. Most independents who do not

lean toward a party share this view (70%).

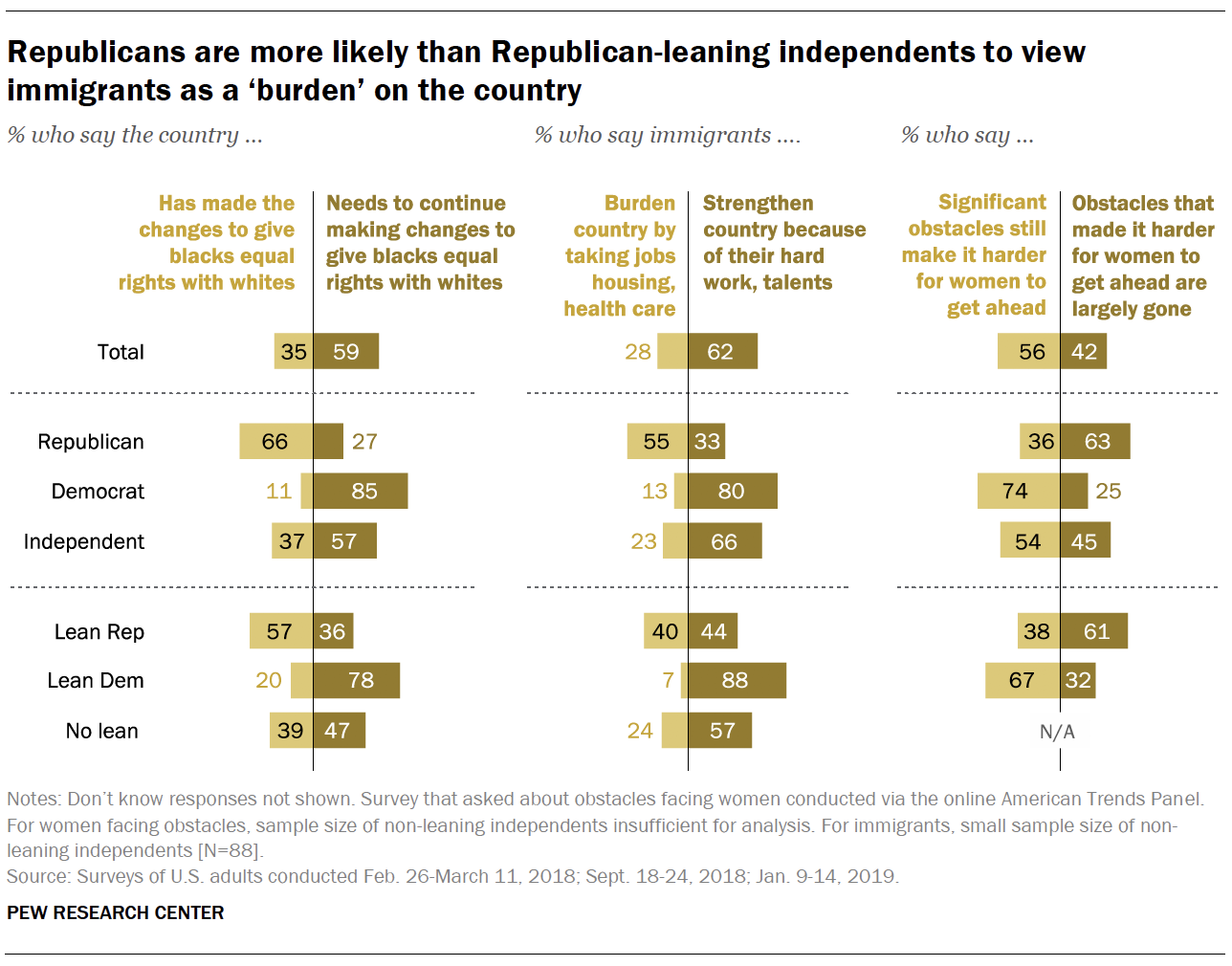

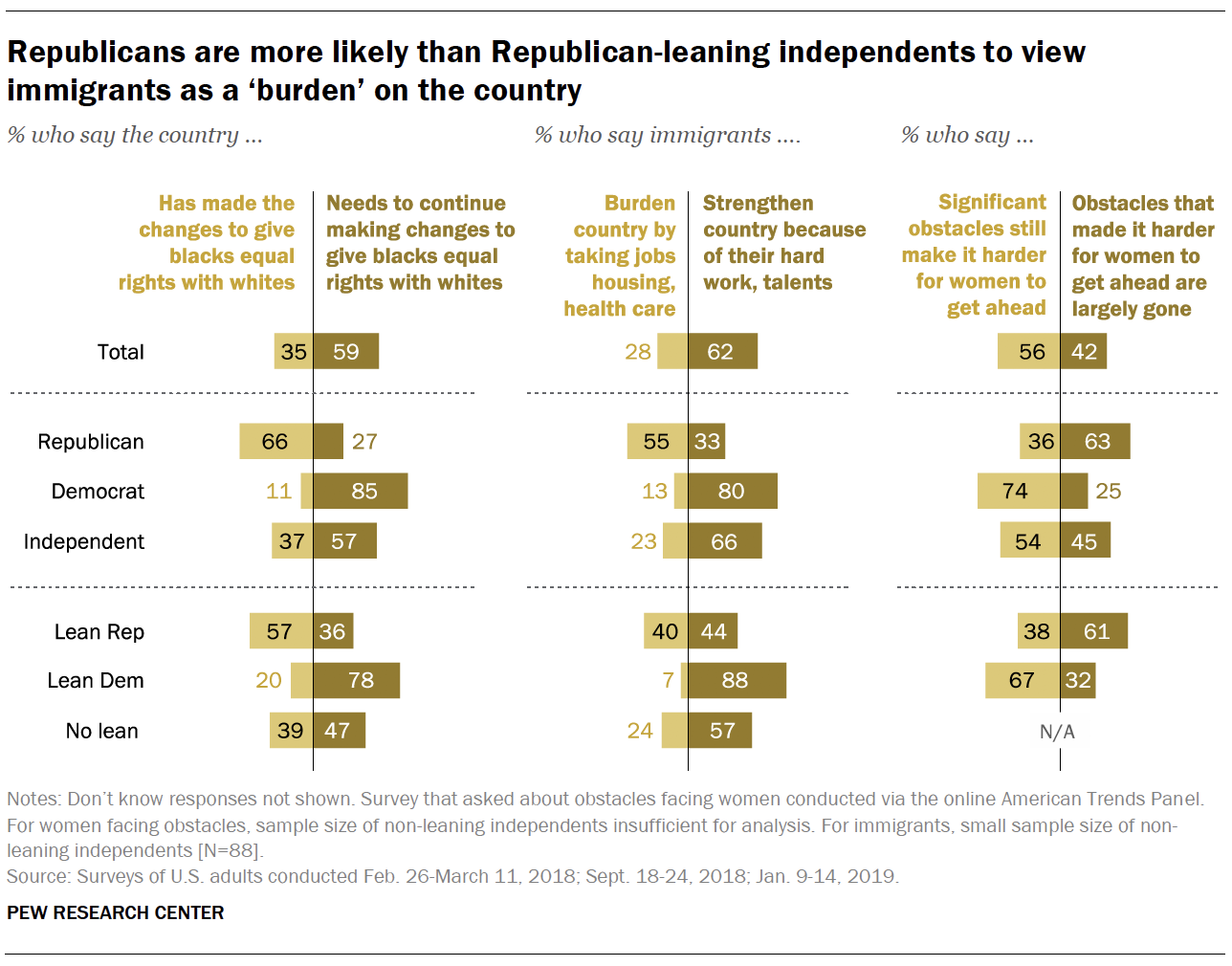

Independents’ views of race, immigrants, gender

Majorities

of independents say the U.S. needs to continue to make changes to give

blacks equal rights with whites (57%) and that significant obstacles

still make it harder for women to get ahead (54%). In addition, far more

independents say immigrants do more to strengthen (66%) than burden

(23%) the country.

In views of racial equality and women’s

progress, the views of partisan leaners are comparable to those of

partisans. Large majorities of Democrats and Democratic leaners say the

U.S. needs to make more changes to give blacks equal rights and that

significant obstacles stand in the way of women. Most Republicans and

Republican leaners say the country has made needed changes to give

blacks equal rights with whites, and that the obstacles blocking women’s

progress are largely gone.

However,

Republican-leaning independents differ from Republicans in their views

of immigrants’ impact on the country. Among GOP leaners, 44% say

immigrants strengthen the country because of their hard work and

talents; 40% say they are a burden on the country because they take

jobs, housing and health care. A majority of those who identify as

Republicans (55%) say immigrants burden the country.

Views of

immigrants’ impact on the country are largely positive among

Democratic-leaning independents (88% say they strengthen the U.S.) and

those who identify as Democrats (80%).

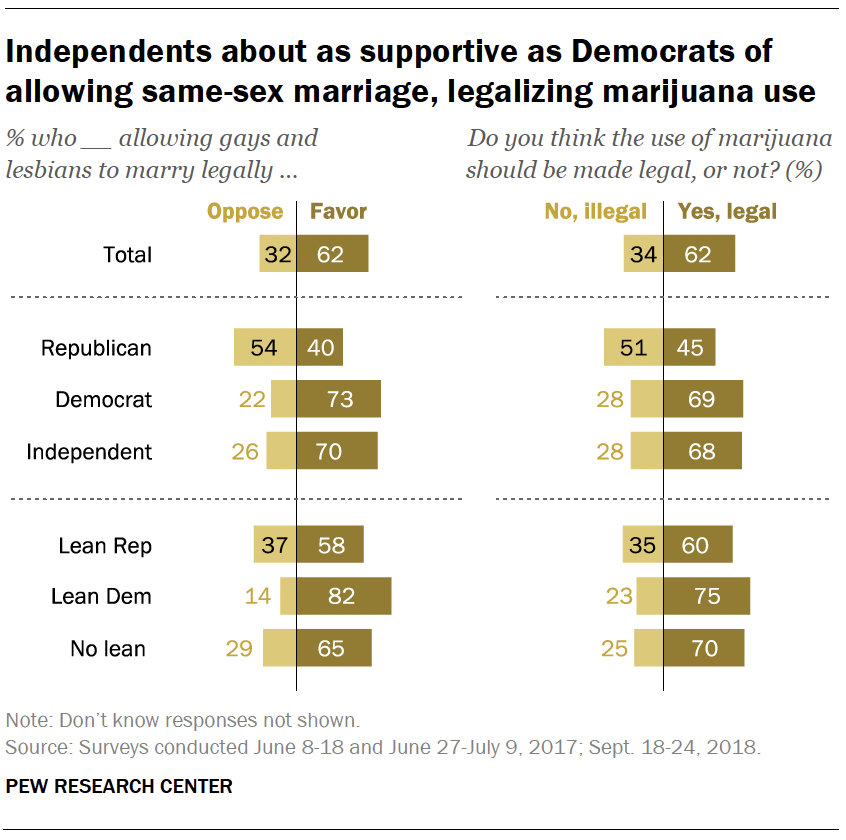

Broad support among independents for same-sex marriage, marijuana legalization

Public support for same-sex marriage has grown rapidly

over the past decade. In June 2017, a majority of adults (62%) favored allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally, while just 32% were opposed.

Independents’

views of same-sex-marriage were similar to Democrats’: 73% of Democrats

favored gay marriage, as did 70% of independents. Among those who

identified as Republicans, just 40% favored same-sex marriage, while 54%

were opposed.

In

contrast to Republicans, Republican-leaning independents favored

same-sex marriage (58% were in favor, 37% were opposed). Support for

same-sex marriage was higher among Democratic-leaning independents than

among Democrats (82% vs. 73%).

Public support

for legalizing marijuana use

has followed a similar upward trajectory in recent years. Currently,

62% of the public says the use of marijuana should be made legal, while

34% say it should be illegal.

Majorities of both Democrats (69%)

and independents (68%) favor legalizing marijuana; Republicans are

divided, with 45% supportive of legalization and 51% opposed. Among

GOP-leaning independents, a 60% majority favors legalizing marijuana.

And a large majority of Democratic-leaning independents (75%) also

favors marijuana legalization.

Independents who do not lean to a

party widely favored same-sex marriage (65% favor this), while 70% say

the use of marijuana should be legal.

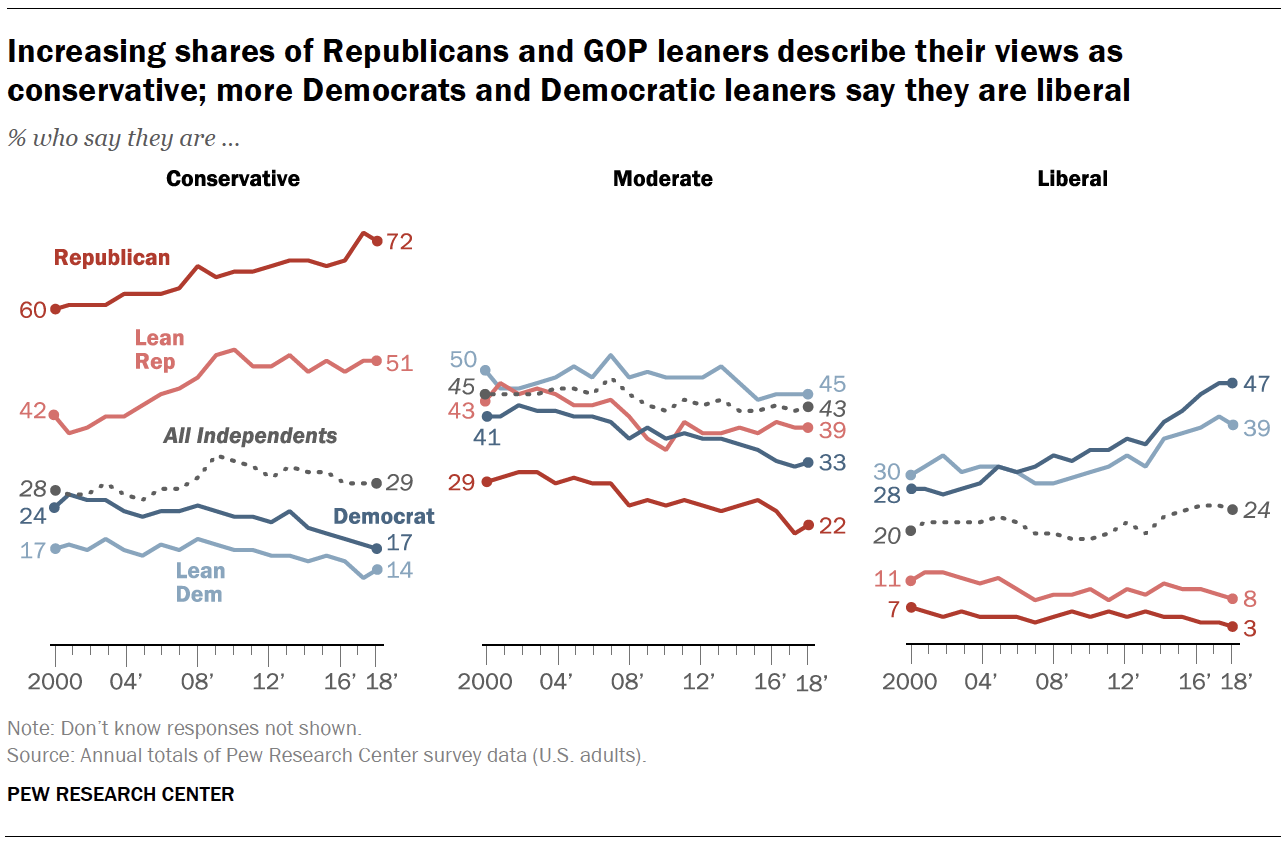

More partisans and partisan leaners embrace ideological labels

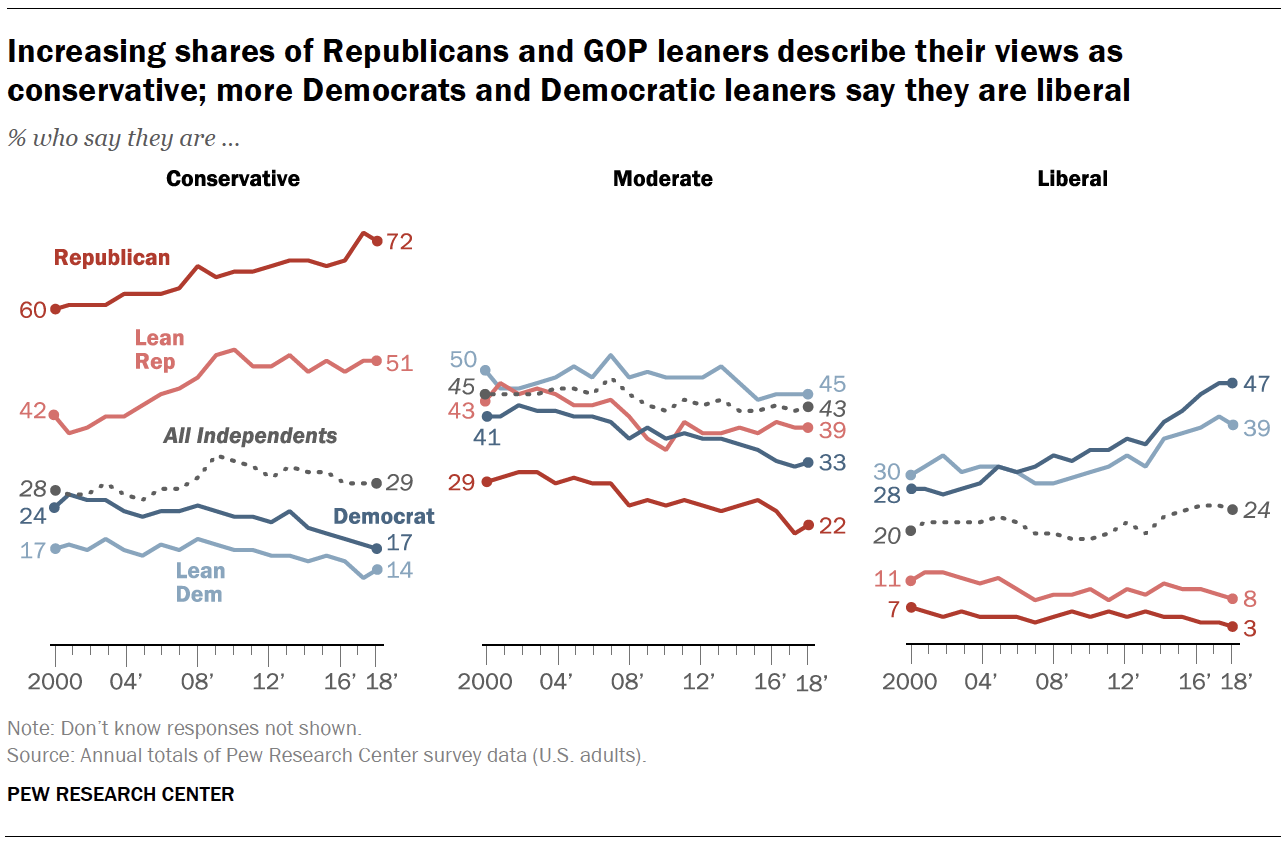

As

in the past, more independents describe their political views as

moderate (43%) than conservative (29%) or liberal (24%). These shares

have changed little in recent years.

Since

2000, there have been sizable increases in the shares of both

Republicans and Republican-leaning independents who identify as

conservative. Today, more Republican-leaning independents describe

themselves as conservatives (51%) than as moderates (39%) or liberals

(8%). In 2000, GOP leaners included almost identical shares of

conservatives (42%) and moderates (43%); 11% described their views as

liberal.

Over the same period, there has been growth in the

shares of Democrats and Democratic leaners identifying as liberal. Among

Democratic-leaning independents, slightly more identify as moderates

(45%) than as liberals (39%), while 14% are conservatives. But the gap

has narrowed since 2000, when moderates outnumbered liberals, 50% to

30%.

By contrast, moderates continue to make up the largest

share of independents who do not lean to a party. Nearly half of

independents who do not lean to a party describe their views as

moderate, while 24% are conservatives and 18% are liberals. These

numbers have changed little since 2000.

How independents view the political parties

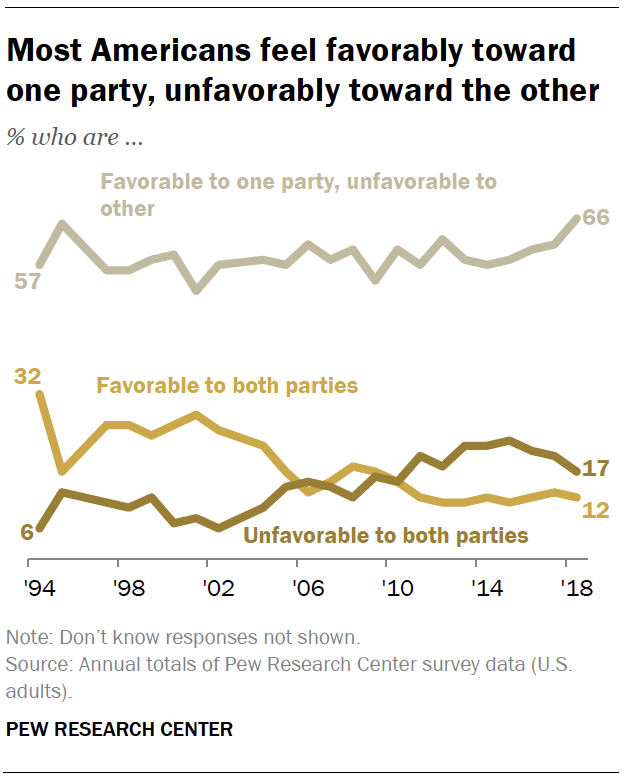

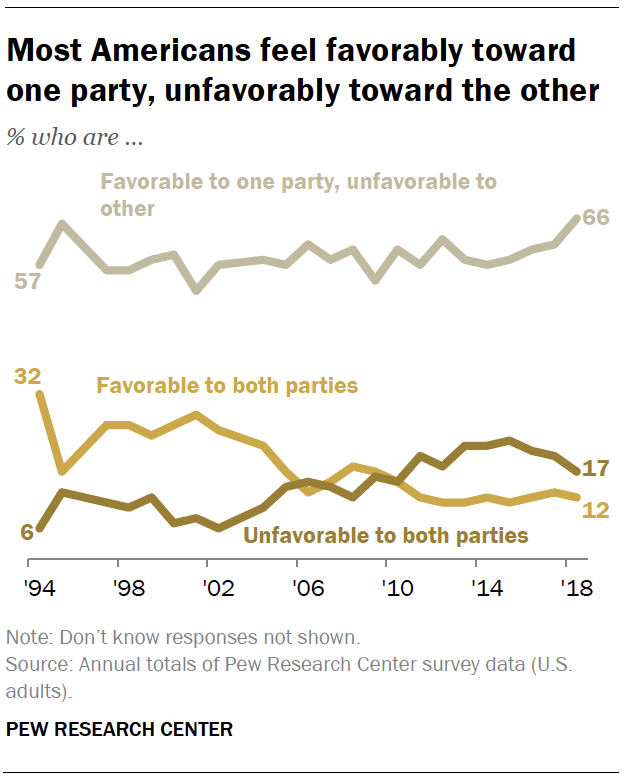

In

a two-party system, it is not surprising that most Americans view their

own party favorably while viewing the opposing party unfavorably.

Two-thirds of Americans (66%) view one party favorably while expressing

an unfavorable opinion of the other party. About one-in-five (17%) feel

unfavorably toward both parties, while 12% feel favorably toward both.

The

share of Americans who have a positive view of one party and a negative

view of the other has increased since 2015 (from 58%). Over the same

period, there has been a decline in the share expressing a negative view

of both parties, from 23% in 2015 to 17% currently.

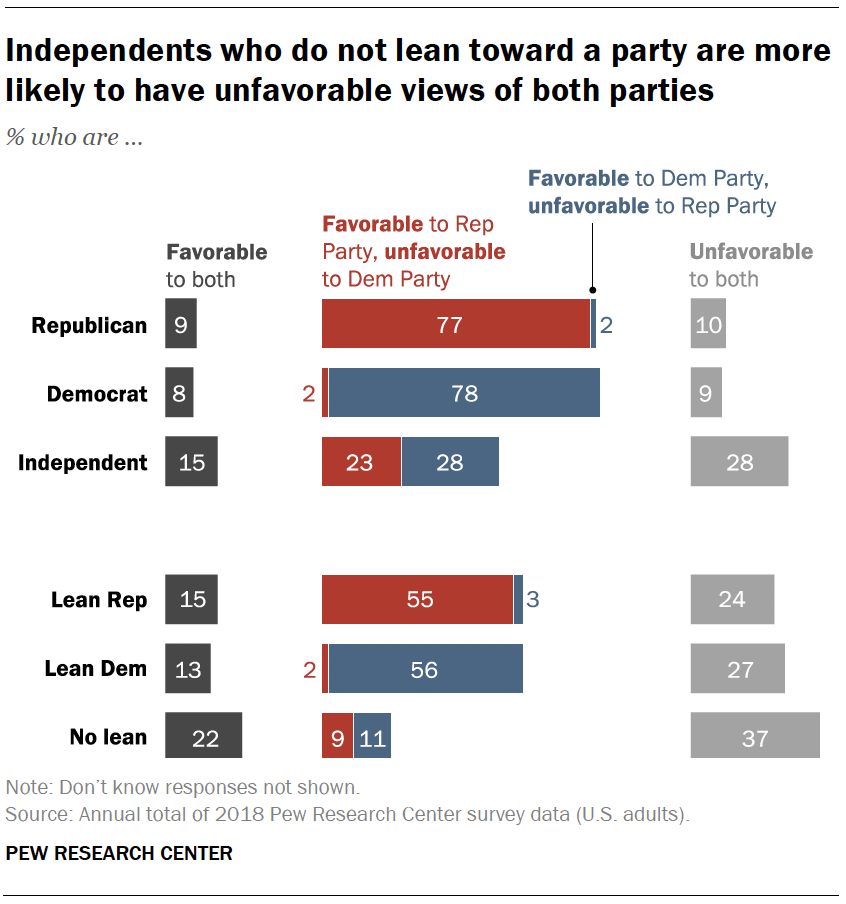

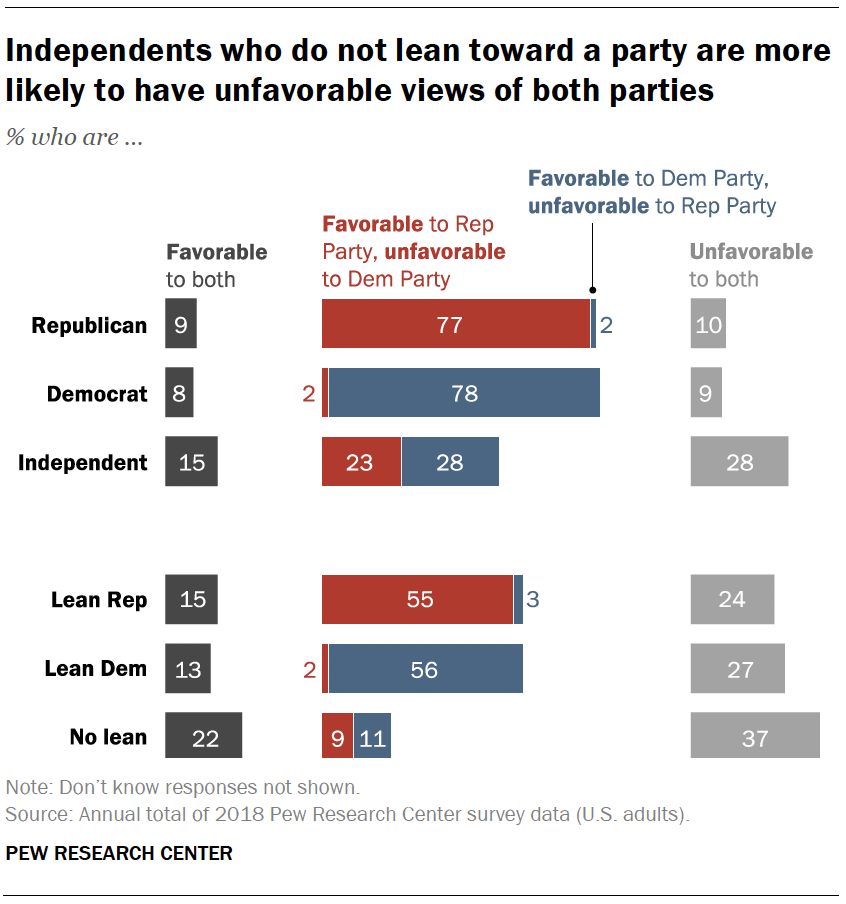

Independents

who lean toward a party are less likely than partisans to view their

party favorably. In addition, far more independents (28%) than

Republicans (10%) or Democrats (9%) have an unfavorable opinion of both

parties.

Still, the share of independents who view both parties

negatively has declined in recent years. At one point in 2015, more than

a third of independents (36%) viewed both parties unfavorably.

Most

of the change since then has come among Republican-leaning

independents, who feel much more positively about the GOP than they did

then.

In July 2015,

just 44% of GOP leaners had a favorable opinion of the Republican

Party; 47% had an unfavorable view of both parties. Today, a majority of

GOP leaners view the Republican Party favorably (55%), while just 24%

view both parties unfavorably.

Independents

who do not lean to a party are most likely to have an unfavorable

opinion of both parties (37%). Another 22% have favorable opinions of

both parties. Just 11% of independents who do not lean to a party view

the Democratic Party favorably, while about as many (9%) have a

favorable view of the GOP.

Growing partisan antipathy among partisans and leaners

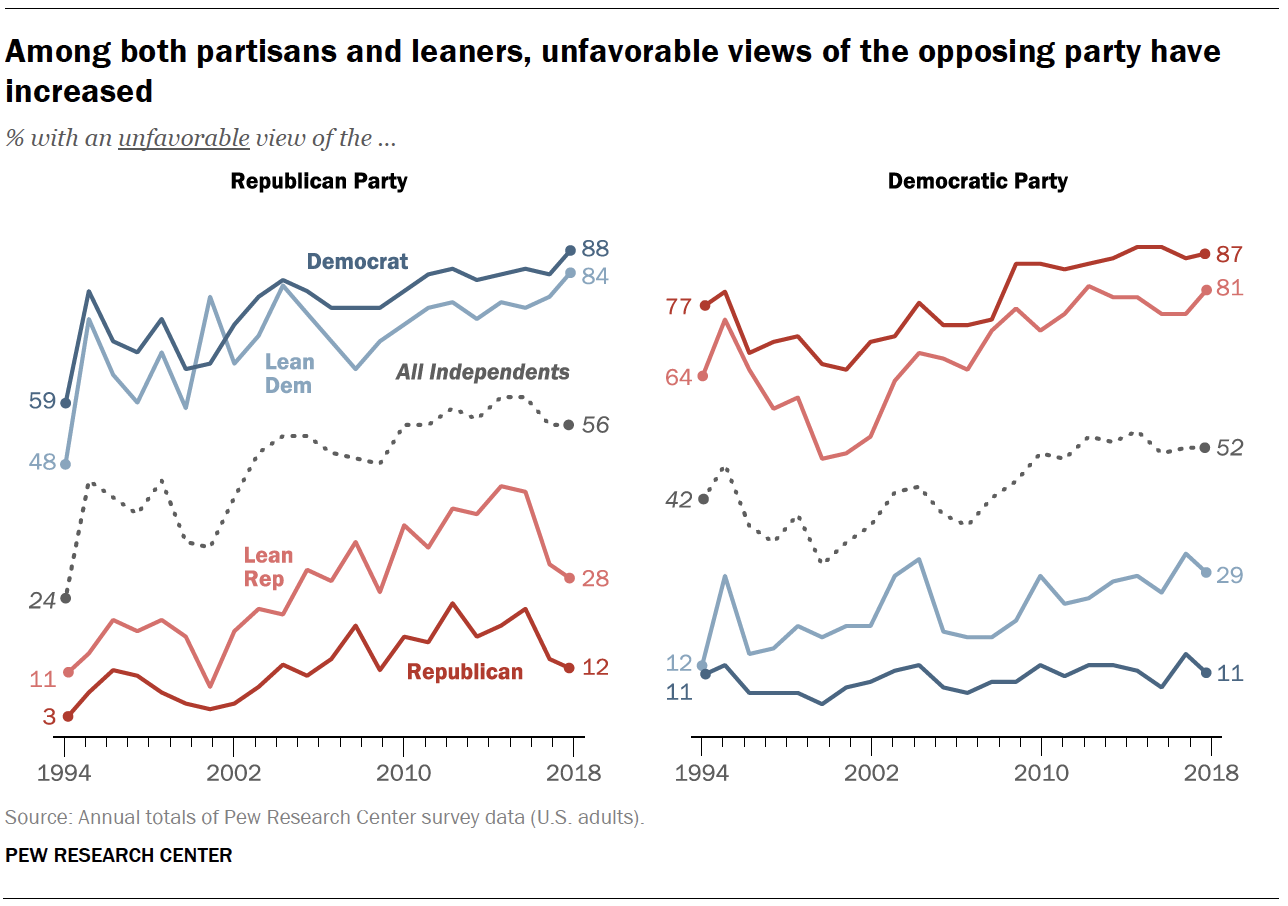

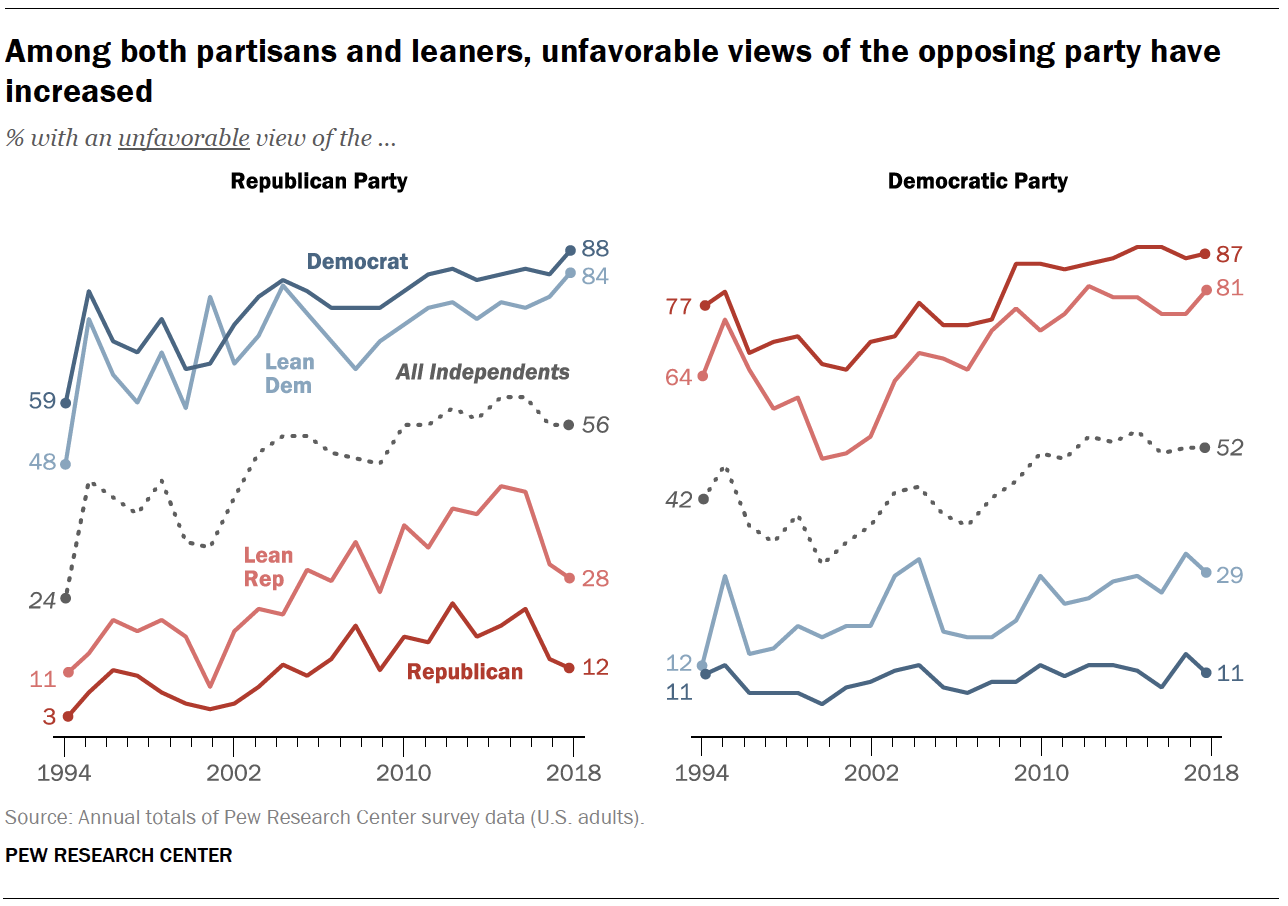

Over

the past two decades, Republicans and Democrats have come to view the

opposing party more negatively. The same trend is evident among

independents who lean toward a party.

Currently, 87% of those

who identify with the Republican Party view the Democratic Party

unfavorably; Republican-leaning independents are almost as likely to

view the Democratic Party negatively (81% unfavorable). Opinions among

Democrats and Democratic leaners are nearly the mirror image: 88% of

Democrats and 84% of Democratic leaners view the GOP unfavorably. In

both parties, the shares of partisan identifiers and leaners with

unfavorable impressions of the opposition party are at or near all-time

highs.

Perhaps more important, intense dislike of the opposing

party, which has surged over the past two decades among partisans, has

followed a similar trajectory among independents who lean toward the

Republican and Democratic parties.

The

share of Democratic-leaning independents with a very unfavorable

opinion of the Republican Party has more than quadrupled between 1994

and 2018 (from 8% to 37%). There has been a similar trend in how

Republican leaners view the Democratic Party; very unfavorable opinions

have increased from 15% in 1994 to 39% in 2018.

Indians

try out electronic voting machines in Mumbai in January, ahead of the

country’s upcoming general elections. (Indranil Mukherjee/AFP/Getty

Images)

Indians

try out electronic voting machines in Mumbai in January, ahead of the

country’s upcoming general elections. (Indranil Mukherjee/AFP/Getty

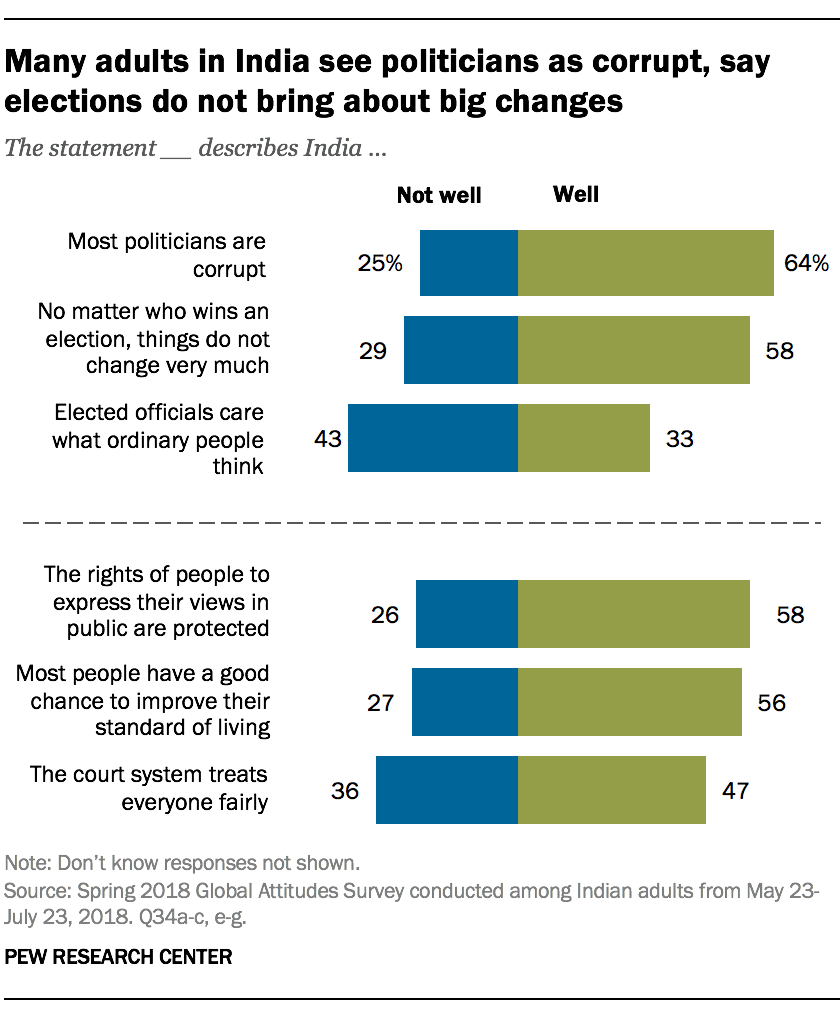

Images)  Most

Indian adults see politicians as corrupt and question whether elections

are effective. About two-thirds (64%) say most politicians are corrupt,

including 43% who very intensely hold this view, according to a spring

2018 survey by the Center. Notably, nearly seven-in-ten supporters of

the two major parties contesting the election – Prime Minister Narendra

Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the opposition Indian National

Congress party – share the view that most elected leaders are corrupt

(69% in each party say this). On a related question, only a third of

Indians think elected officials care about the opinions of ordinary

people in their country.

Most

Indian adults see politicians as corrupt and question whether elections

are effective. About two-thirds (64%) say most politicians are corrupt,

including 43% who very intensely hold this view, according to a spring

2018 survey by the Center. Notably, nearly seven-in-ten supporters of

the two major parties contesting the election – Prime Minister Narendra

Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the opposition Indian National

Congress party – share the view that most elected leaders are corrupt

(69% in each party say this). On a related question, only a third of

Indians think elected officials care about the opinions of ordinary

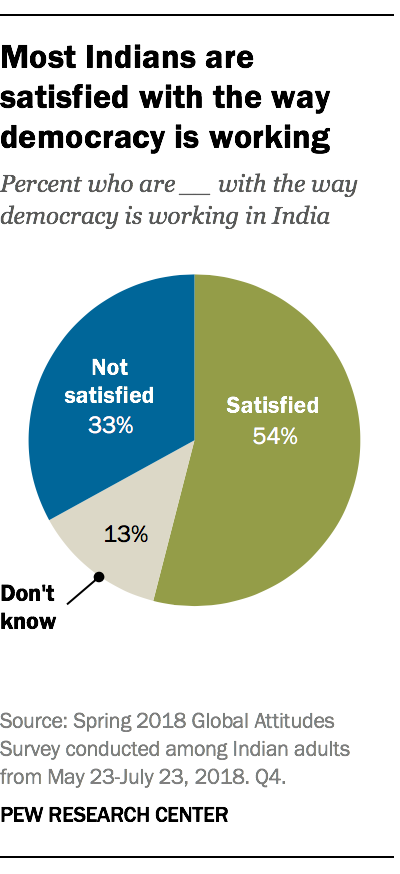

people in their country.  A

little over half of Indian adults (54%) are satisfied with the way

democracy is working in their country, but a third are dissatisfied. Men

are more likely than women to give Indian democracy a thumbs-up, though

one-in-five women decline to offer an opinion. Satisfaction with the

state of India’s democracy also differs by party affiliation:

Three-quarters of BJP supporters are satisfied, compared with only 42%

of Congress adherents.

A

little over half of Indian adults (54%) are satisfied with the way

democracy is working in their country, but a third are dissatisfied. Men

are more likely than women to give Indian democracy a thumbs-up, though

one-in-five women decline to offer an opinion. Satisfaction with the

state of India’s democracy also differs by party affiliation:

Three-quarters of BJP supporters are satisfied, compared with only 42%

of Congress adherents.

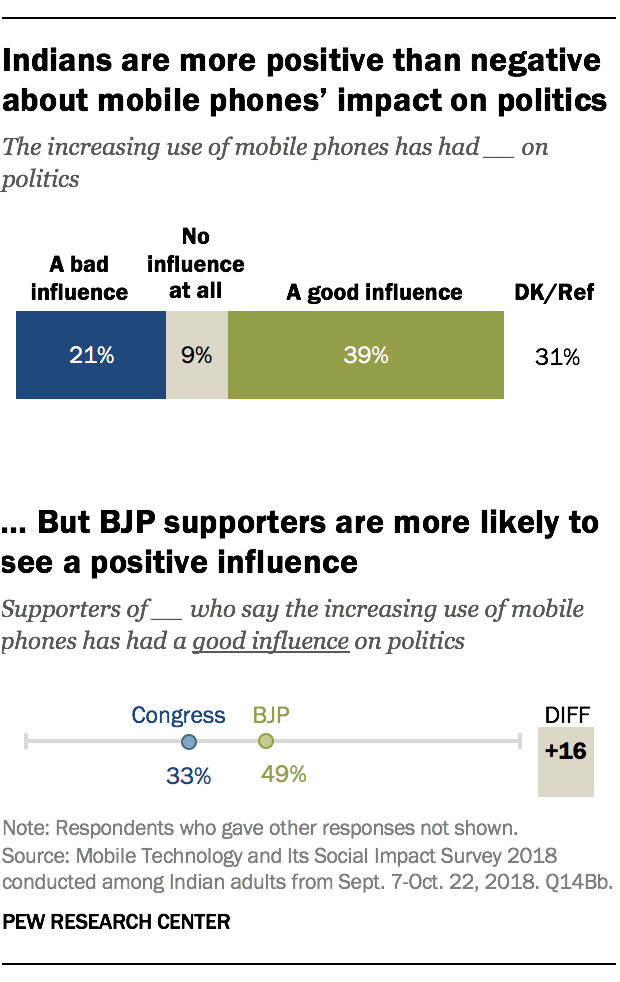

Many

Indians are using mobile phones to get news, but the public is divided

over how these devices have influenced politics. About eight-in-ten

Indian adults say they own or share a mobile phone, and most of these

users (81%) say their phone has helped them obtain information and news

about important issues, according to a separate 2018 survey. However,

Indians have mixed attitudes about mobile phones’ overall impact on

politics. About four-in-ten say the increasing use of mobile phones has

had a good influence on politics. Indians feel similarly about the

impact of the internet on politics: Again, about four-in-ten say it has

had a good influence. However, only a minority of Indians (38%) currently go online.

Many

Indians are using mobile phones to get news, but the public is divided

over how these devices have influenced politics. About eight-in-ten

Indian adults say they own or share a mobile phone, and most of these

users (81%) say their phone has helped them obtain information and news

about important issues, according to a separate 2018 survey. However,

Indians have mixed attitudes about mobile phones’ overall impact on

politics. About four-in-ten say the increasing use of mobile phones has

had a good influence on politics. Indians feel similarly about the

impact of the internet on politics: Again, about four-in-ten say it has

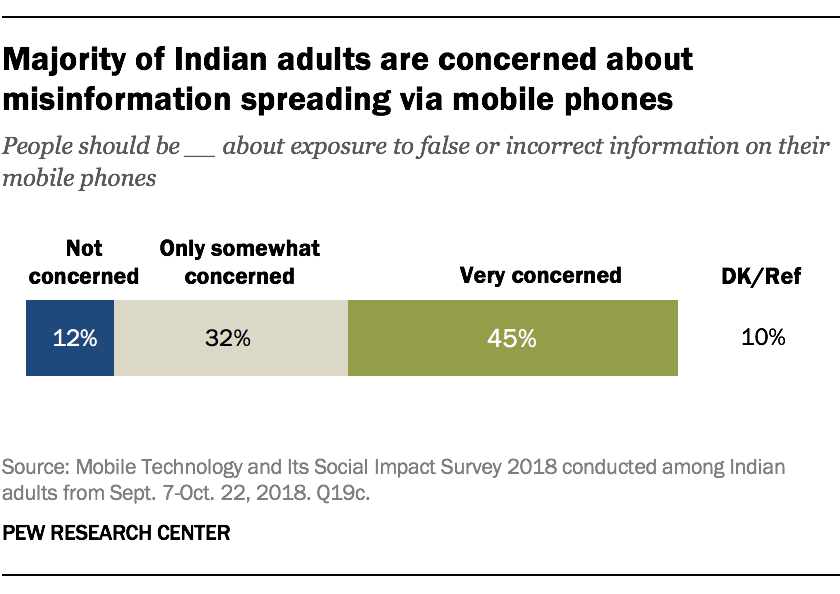

had a good influence. However, only a minority of Indians (38%) currently go online.  Roughly

three-in-four Indians (77%) say they are very or somewhat concerned

about people being exposed to false or incorrect information when they

use their mobile phones, including 45% who are very concerned. Similar

shares of both BJP and Congress supporters say they are very concerned.

This finding comes amid recent violent attacks attributed to viral WhatsApp hoaxes and concerns about the app being used to spread fake news.

Roughly

three-in-four Indians (77%) say they are very or somewhat concerned

about people being exposed to false or incorrect information when they

use their mobile phones, including 45% who are very concerned. Similar

shares of both BJP and Congress supporters say they are very concerned.

This finding comes amid recent violent attacks attributed to viral WhatsApp hoaxes and concerns about the app being used to spread fake news.

A reading comprehension passage from a US standardized test, written by a human.

A reading comprehension passage from a US standardized test, written by a human. A passage written by OpenAI's downgraded GPT-2.

A passage written by OpenAI's downgraded GPT-2.