By Rubén Weinsteiner

Pew

Research Center has conducted many surveys about abortion over the

years, providing a lens into Americans’ views on whether the procedure

should be legal, among a host of other questions. In our

most recent survey,

61% of U.S. adults say abortion should be legal all or most of the

time, while 37% say it should be illegal all or most of the time.

With the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in

Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization overturning

Roe v. Wade,

the 1973 case that effectively legalized abortion nationwide, here is a

look at the most recent available data about abortion from sources

other than public opinion surveys.

How we did this

How many abortions are there in the United States each year?

An

exact answer is hard to come by. Two organizations – the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Guttmacher Institute – try

to measure this, but they use different methods and publish different

figures.

The CDC compiles figures voluntarily reported by the

central health agencies of the vast majority of states (including

separate figures for New York City) and the District of Columbia. Its

latest totals do not include figures from California, Maryland or New

Hampshire, which did not report data to the CDC. (Read the

methodology from the latest CDC report.)

The

Guttmacher Institute compiles its figures after contacting every known

provider of abortions – clinics, hospitals and physicians’ offices – in

the country. It uses questionnaires and health department data, and it

provides estimates for abortion providers that don’t respond to its

inquiries. In part because Guttmacher includes figures (and in some

instances, estimates) from all 50 states, its totals are higher than the

CDC’s. The institute’s latest full report, and its methodology, can be

found here.

While the Guttmacher Institute supports abortion rights, its empirical

data on abortions in the United States has been widely cited by

groups and

publications across the political spectrum, including by a

number of those that

disagree with its positions.

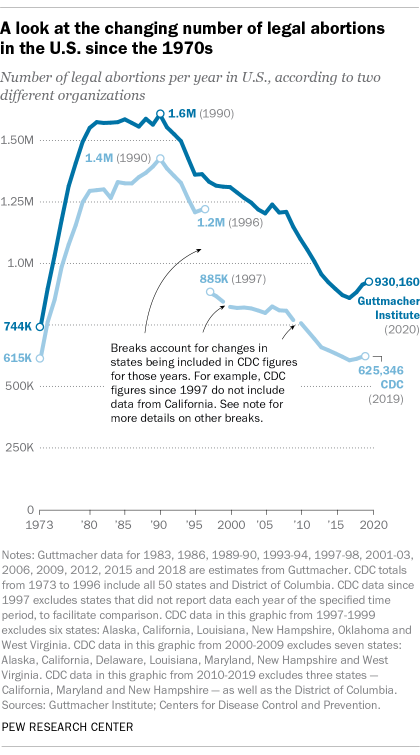

The

last year for which the CDC reported a yearly national total for

abortions is 2019. The agency says there were 629,898 abortions

nationally that year, slightly up from 619,591 in 2018. Guttmacher’s

latest available figures are from 2020, when it says there were 930,160

abortions nationwide, up from 916,460 in 2019.

It’s worth noting

that the figures reported by both organizations include only the legal

induced abortions conducted by clinics, hospitals or physicians’

offices, or that make use of abortion pills dispensed from certified

facilities such as clinics or physicians’ offices. They do not account

for the use of abortion pills that were obtained

outside of clinical settings.

How has the number of abortions in the U.S. changed over the years?

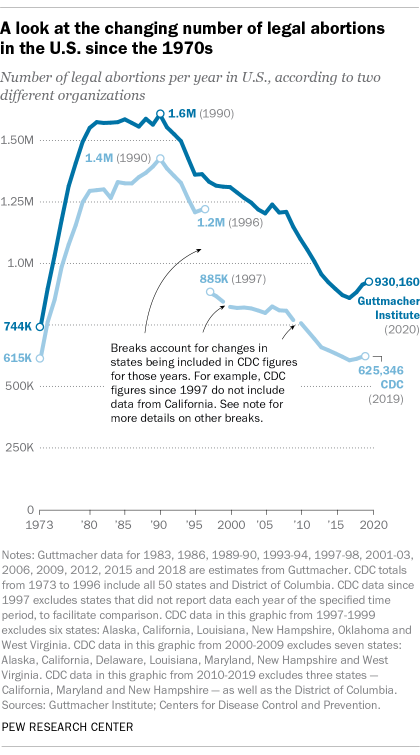

The

annual number of U.S. abortions rose for years after Roe v. Wade

legalized the procedure in 1973, reaching its highest levels around the

late 1980s and early 1990s, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher.

Since then it has generally decreased at what a CDC analysis called

“a slow yet steady pace.” Guttmacher

recorded more than 1.5 million abortions in the U.S. in 1991, about

two-thirds more than the 930,160 it reported for 2020. The CDC reported

just over 1 million abortions in 1991 and 629,898 in 2019, looking at

just the District of Columbia and the 47 states that reported figures in

both years. (This line graph shows the long-term trend in the number of

legal abortions reported by both organizations. To allow for consistent

comparisons over time, the CDC figures in the chart have been adjusted

to ensure that the same states are counted from one year to the next.

Using that approach, the CDC figure for 2019 is 625,346 legal

abortions.)

There have been occasional breaks in this long-term

pattern of decline – during the middle of the first decade of the 2000s,

and then again in the late 2010s. The CDC reported modest 1% and 2%

increases in abortions in 2018 and 2019, respectively, while Guttmacher

reported an 8% increase in abortions over the three-year period from

2017 to 2020.

As noted above, these figures do not include abortions that use pills that were obtained outside of clinical settings.

What is the abortion rate among women in the U.S.? How has it changed over time?

Guttmacher

says that in 2020 there were 14.4 abortions in the U.S. per 1,000 women

ages 15 to 44. Its data shows that the rate of abortions among women

has generally been declining in the U.S. since 1981, when it reported

there were 29.3 abortions per 1,000 women in that age range.

The

CDC says that in 2019, there were 11.4 abortions in the U.S. per 1,000

women ages 15 to 44. (That figure excludes California, Maryland, New

Hampshire and the District of Columbia.) Like Guttmacher’s data, the

CDC’s figures also suggest a general decline in the abortion rate over

time. In 1980, when the CDC reported on all 50 states and D.C., it said

there were 25 abortions per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44.

That

said, both Guttmacher and the CDC say there were slight increases in the

rate of abortions during the late 2010s. Guttmacher says the abortion

rate per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44 rose from 13.5 in 2017 to 14.4 in

2020. The CDC says it rose from 11.2 in 2017 to 11.4 in 2019. (The CDC’s

figures for both of those years exclude data from California, Maryland,

New Hampshire and the District of Columbia).

What are the most common types of abortion?

The

CDC broadly divides abortions into two categories: surgical abortions

and medication abortions. In 2019, 56% of legal abortions in clinical

settings occurred via some form of surgery, while 44% were medication

abortions involving pills, according to the CDC. Since the Food and Drug

Administration first approved abortion pills in 2000, their use has

increased over time as a share of abortions nationally. Guttmacher’s

preliminary data

from its forthcoming study says that 2020 was the first time that more

than half of all abortions in clinical settings in the U.S. were

medication abortions.

Two pills commonly used together for

medication abortions are mifepristone, which, taken first, blocks

hormones that support a pregnancy, and misoprostol, which then causes

the uterus to empty. Medication abortion is

approved for use until 10 weeks into pregnancy.

Surgical abortions conducted

during the first trimester of pregnancy typically use a suction process, while the relatively few surgical abortions that occur

during the second trimester of a pregnancy typically use a process called dilation and evacuation, according to the UCLA School of Medicine website.

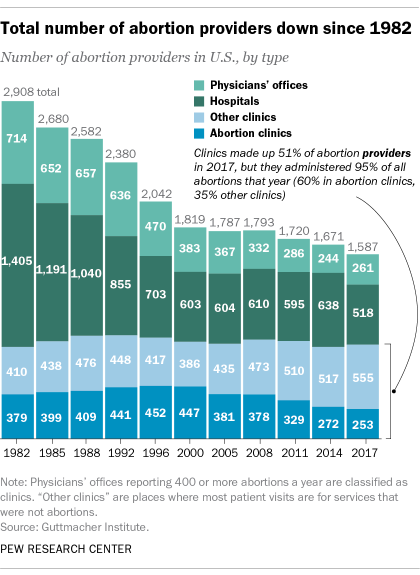

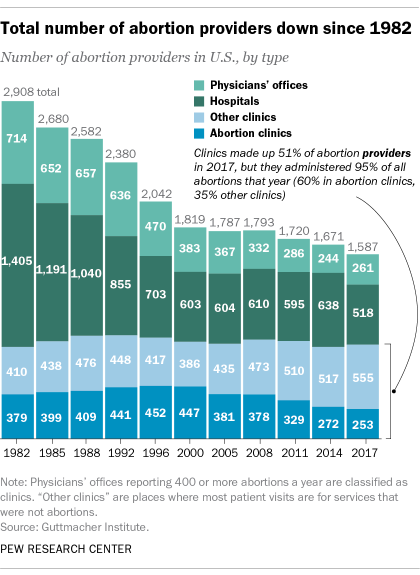

How many abortion providers are there in the U.S., and how has that number changed over time?

In 2017, there were 1,587 facilities in the U.S. that provided abortions,

according to Guttmacher. This included 808 clinics, 518 hospitals and 261 physicians’ offices.

While

clinics make up a slight majority (51%) of the facilities that provide

abortions, they are the sites where the vast majority (95%) of abortions

occur, including 60% at specialized abortion clinics and 35% at

nonspecialized clinics, according to the 2017 data from Guttmacher.

Hospitals made up 33% of the facilities that provided abortions but

accounted for only 3% of abortions that year, while just 1% of abortions

were conducted by physicians’ offices.

Looking just at clinics –

that is, the total number of specialized abortion clinics and

nonspecialized clinics in the U.S. – Guttmacher found a 2% increase

between 2014 and 2017. However, there were regional differences. In the

Northeast, the number of clinics that provide abortions increased by 16%

during those years, and in the West by 4%. The number of clinics

decreased during those years by 9% in the South and 6% in the Midwest.

The

total number of abortion providers has declined dramatically since the

1980s. In 1982, according to Guttmacher, there were 2,908 facilities

providing abortions in the U.S., including 789 clinics, 1,405 hospitals

and 714 physicians’ offices.

Later this year, Guttmacher is

expected to publish a similar breakdown of the types of abortion

providers for 2020. The CDC does not track the number of abortion

providers.

What percentage of abortions are for women who live in a different state from the abortion provider?

In

the District of Columbia, New York City and the 47 states that provided

information to the CDC in 2019, 9.3% of all abortions were performed on

women whose state of residency was known to be different than the state

where the abortion occurred – virtually the same percentage as in the

previous year.

The share of reported abortions performed on

women outside their state of residence was much higher before the 1973

Roe decision that stopped states from banning abortion. In 1972, 41% of

all abortions in D.C. or the 20 states that provided this information to

the CDC that year were performed on women outside their state of

residence. In 1973, the corresponding figure was 21% in D.C. and the 41

states that provided this information, and in 1974 it was 11% in D.C.

and the 43 states that provided data.

Anticipating that many

states will further restrict abortion access, politicians in some states

with permissive abortion laws such as

New York,

California and

Oregon are expecting more women from states with less abortion access to travel to their states for an abortion.

What are the demographics of women who had abortions in 2019?

In the District of Columbia and 47 states that reported data to

the CDC

in 2019, the majority of women who had abortions (57%) were in their

20s, while about three-in-ten (31%) were in their 30s. Teens ages 13 to

19 accounted for 9% of those who had abortions, while women in their 40s

accounted for 4%.

The vast majority of women who had abortions in 2019 were unmarried (85%), while married women accounted for 15%, according to

the CDC, which had data on this from 41 states and New York City (but not the rest of New York).

In the District of Columbia and 29 states that reported racial and ethnic data on abortion to

the CDC,

38% of all women who had abortions in 2019 were non-Hispanic Black,

while 33% were non-Hispanic White, 21% were Hispanic, and 7% were of

other races or ethnicities.

Among

those ages 15 to 44, there were 23.8 abortions per 1,000 non-Hispanic

Black women; 11.7 abortions per 1,000 Hispanic women; 6.6 abortions per

1,000 non-Hispanic White women; and 13 abortions per 1,000 women of

other races or ethnicities in that age range, the

CDC reported from those same 29 states and the District of Columbia.

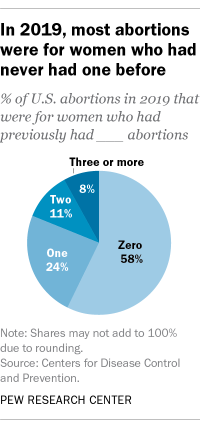

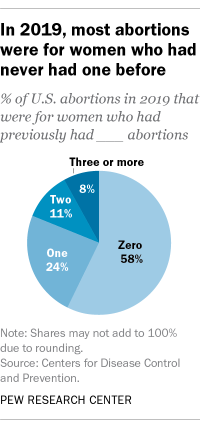

For 58% of U.S. women who had induced abortions in 2019, it was the first time they had ever had one,

according to the CDC.

For nearly a quarter (24%), it was their second abortion. For 11% of

women, it was their third, and for 8% it was their fourth or higher.

These CDC figures include data from 43 states and New York City (but not

the rest of New York).

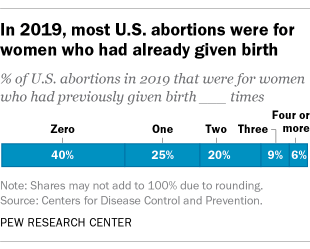

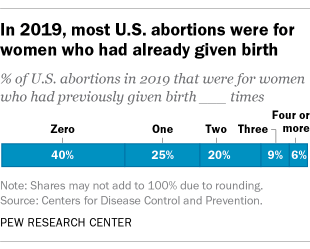

Four-in-ten women who had abortions in 2019 (40%) had no previous live births at the time they had an abortion,

according to the CDC.

A quarter of women (25%) who had abortions in 2019 had one previous

live birth, 20% had two previous live births, 9% had three, and 6% had

four or more previous live births. These CDC figures include data from

44 states and New York City (but not the rest of New York).

When during pregnancy do most abortions occur?

The

vast majority of abortions – around nine-in-ten – occur during the

first trimester of a pregnancy. In 2019, 93% of abortions occurred

during the first trimester – that is, at or before 13 weeks of

gestation,

according to the CDC.

An additional 6% occurred between 14 and 20 weeks of pregnancy, and 1%

were performed at 21 weeks or more of gestation. These CDC figures

include data from 42 states and New York City (but not the rest of New

York).

How often are there medical complications from abortion?

About 2% of all abortions in the U.S. involve some type of complication for the woman, according to the

National Center for Biotechnology Information,

which is part of the U.S. National Library of Medicine, a branch of the

National Institutes of Health. The center says that “most complications

are considered minor such as pain, bleeding, infection and

post-anesthesia complications.”

The CDC calculates

case-fatality rates

for women from legal induced abortions – that is, how many women die

from complications from abortion, for every 100,000 abortions that occur

in the U.S. The rate was lowest during the most recent period examined

by the agency (2013 to 2018), when there were 0.4 deaths to women per

100,000 legal induced abortions. The case-fatality rate reported by the

CDC was highest during the first period examined by the agency (1973 to

1977), when it was 2.1 deaths to women per 100,000 legal induced

abortions. During the five-year periods in between, the figure ranged

from 0.5 (from 1993 to 1997) to 0.8 (from 1978 to 1982). The CDC says it

calculates death rates by five-year and six-year periods because of

year-to-year fluctuation in the numbers and due to the relatively low

number of women who die from abortion.

Two women died from

induced abortion in the U.S. in 2018, in both cases from abortions that

were legal, according to the CDC. The same was true in 2017. In 2016,

the CDC reported seven deaths from either legal (six) or illegal (one)

induced abortions. Since 1990, the annual number of deaths among women

due to induced abortion has ranged from two to 12, according to the CDC.

The annual number of reported deaths from induced abortions

tended to be higher in the 1980s, when it ranged from nine to 16, and

from 1972 to 1979, when it ranged from 13 to 54 (1972 was the first year

the CDC began collecting this data). One driver of the decline was the

drop in deaths from illegal abortions. There were 35 deaths from illegal

abortions in 1972, the last full year before Roe v. Wade. The total

fell to 19 in 1973 and to single digits or zero every year after that.

(The number of deaths from legal abortions has also declined since then,

though with some slight variation over time.)

The number of

deaths from induced abortions was considerably higher in the 1960s than

afterward. For instance, there were 235 deaths from abortions in

1965 and 280 in

1963,

according to reports by the then-U.S. Department of Health, Education

and Welfare, a precursor to the Department of Health and Human Services.

The CDC is a division of Health and Human Services.