The public renders a harsh judgment on the state of political discourse in this country. And for many Americans, their own conversations about politics have become stressful experiences that they prefer to avoid.

Large

majorities say the tone and nature of political debate in the United

States has become more negative in recent years – as well as less

respectful, less fact-based and less substantive.

Large

majorities say the tone and nature of political debate in the United

States has become more negative in recent years – as well as less

respectful, less fact-based and less substantive. Meanwhile, people’s everyday conversations about politics and other sensitive topics are often tense and difficult. Half say talking about politics with people they disagree with politically is “stressful and frustrating.”

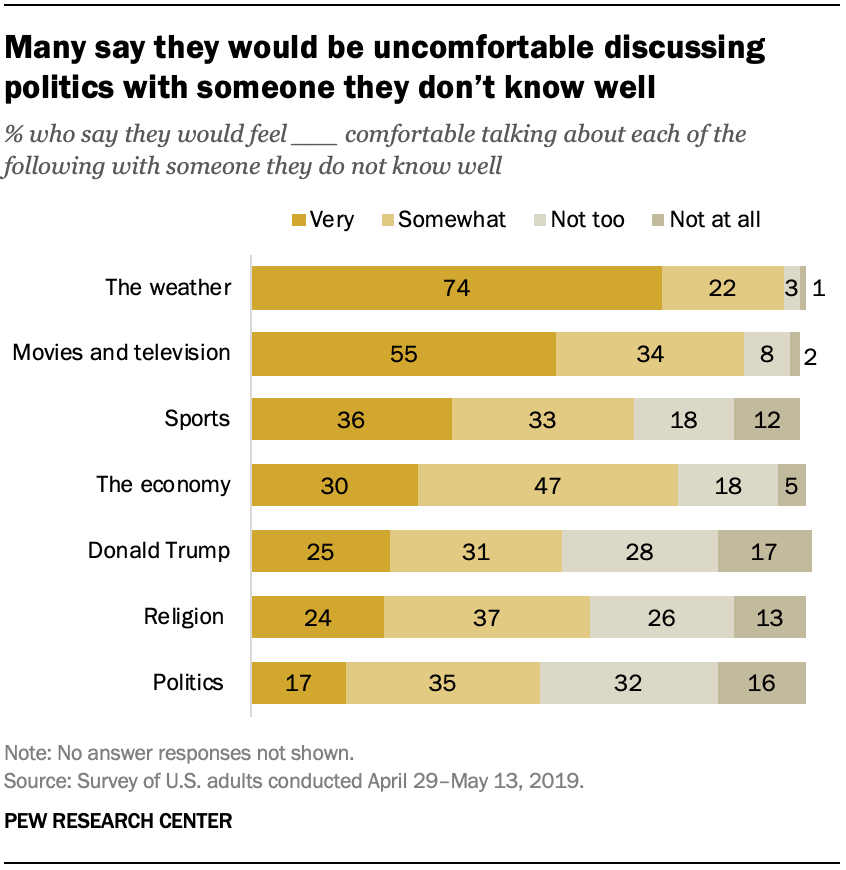

When speaking with people they do not know well, more say they would be very comfortable talking about the weather and sports – and even religion – than politics. And it is people who are most comfortable with interpersonal conflict, including arguing with other people, who also are most likely to talk about politics frequently and to be politically engaged.

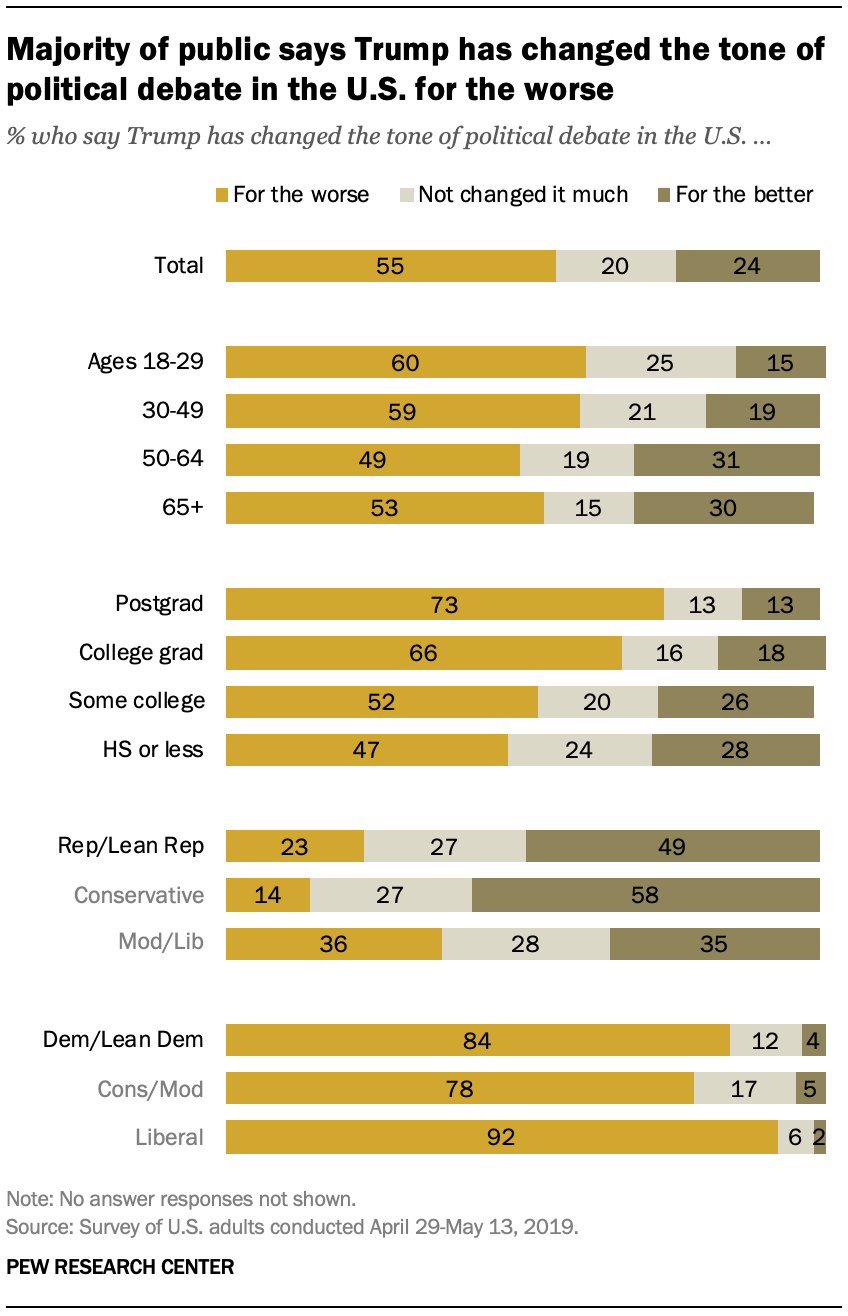

Donald Trump is a major factor in people’s views about the state of the nation’s political discourse. A 55% majority says Trump has changed the tone and nature of political debate in this country for the worse; fewer than half as many (24%) say he has changed it for the better, while 20% say he has had little impact.

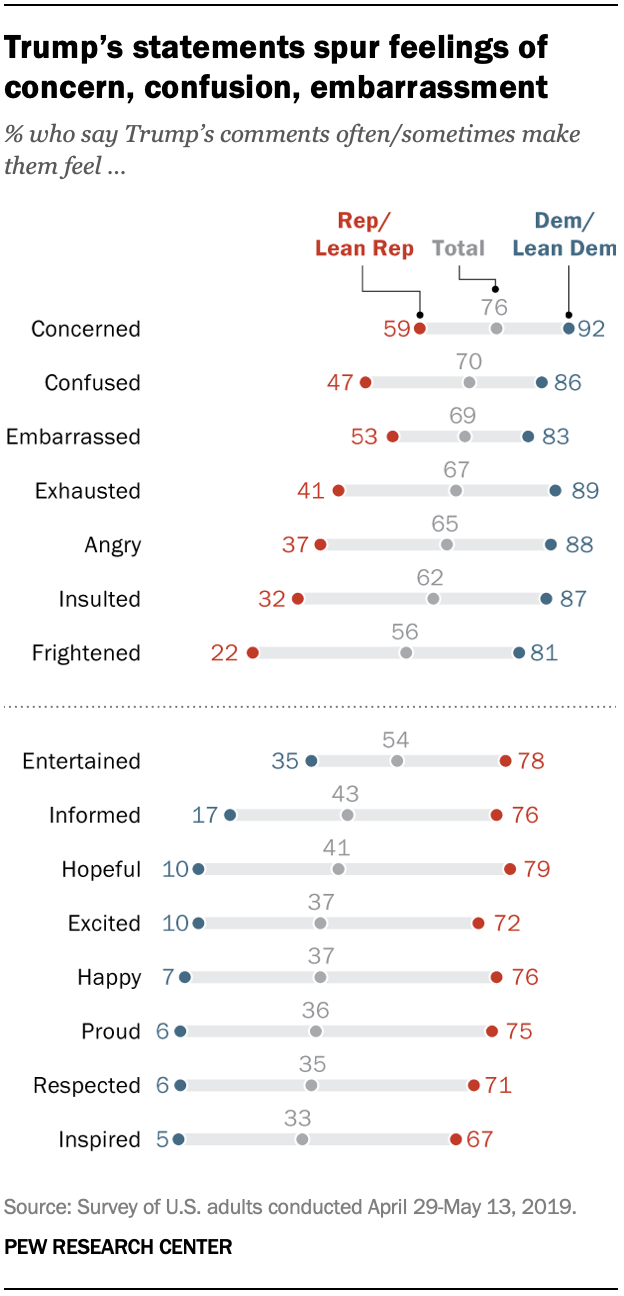

Perhaps more striking are the public’s feelings about the things Trump says: sizable majorities say Trump’s comments often or sometimes make them feel concerned (76%), confused (70%), embarrassed (69%) and exhausted (67%). By contrast, fewer have positive reactions to Trump’s rhetoric, though 54% say they at least sometimes feel entertained by what he says.

Pew Research Center’s wide-ranging survey of attitudes about political speech and discourse in the U.S. was conducted April 29-May 13 among 10,170 adults. Among the other major findings:

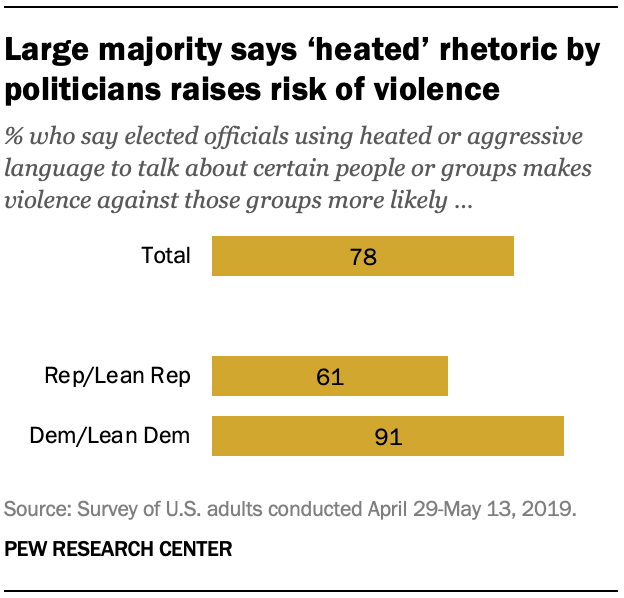

Broad

agreement on the dangers of “heated or aggressive” rhetoric by

political leaders. A substantial majority (78%) says “heated or

aggressive” language directed by elected officials against certain

people or groups makes violence against them more likely. This view is

more widely shared among Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents

than Republican and Republican leaners.

Broad

agreement on the dangers of “heated or aggressive” rhetoric by

political leaders. A substantial majority (78%) says “heated or

aggressive” language directed by elected officials against certain

people or groups makes violence against them more likely. This view is

more widely shared among Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents

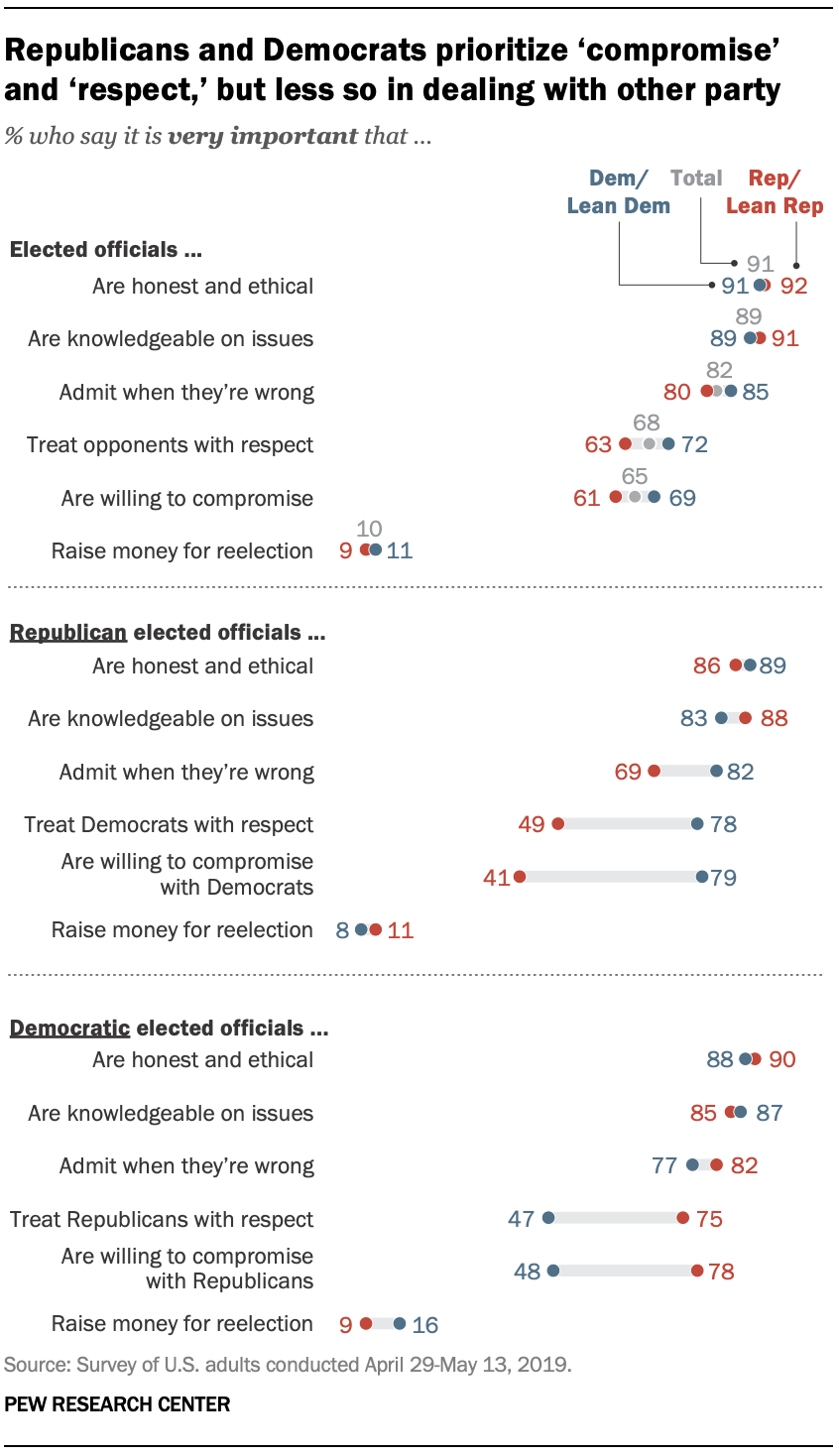

than Republican and Republican leaners. Partisans demand a higher standard of conduct from the other party than from their own. Majorities in both parties say it is very important that elected officials treat their opponents with respect. But while most Democrats (78%) say it is very important for Republican elected officials to treat Democratic officials with respect, only about half (47%) say it is very important for officials from their party to treat Republican politicians with respect. There is similar divide in the opinions of Republicans; 75% say Democrats should be respectful of GOP officials, while only 49% say the same about Republicans’ treatment of Democratic officials.

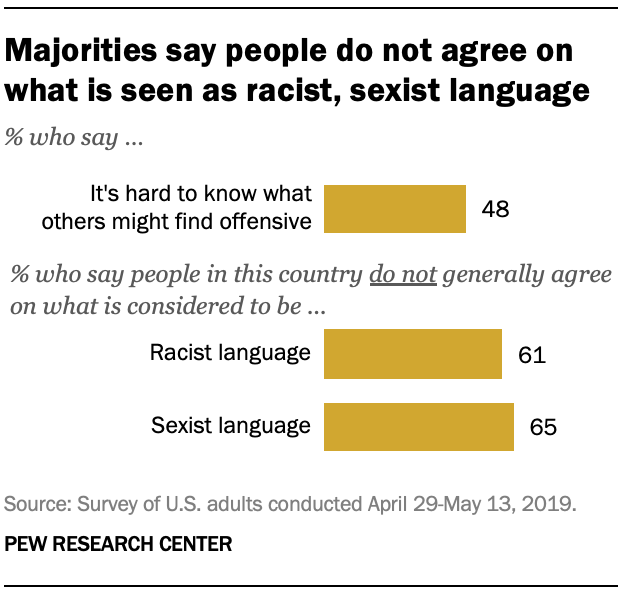

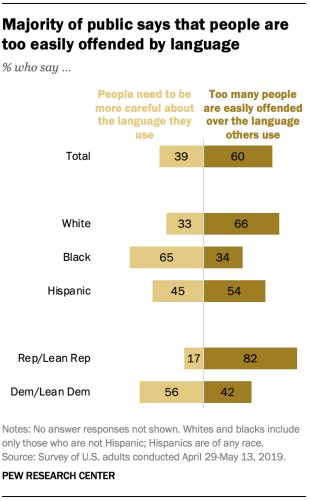

Uncertainty

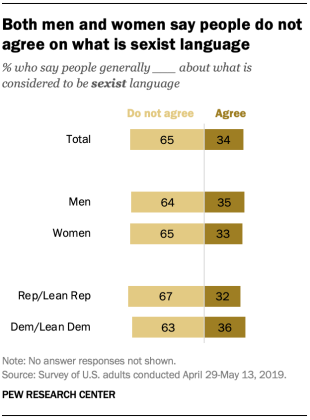

about what constitutes “offensive” speech. As in the past, a majority

of Americans (60%) say “too many people are easily offended over the

language that others use.” Yet there is uncertainty about what

constitutes offensive speech: About half (51%) say it is easy to know

what others might find offensive, while nearly as many (48%) say it is

hard to know. In addition, majorities say that people in this country do

not generally agree about the types of language considered to be sexist

(65%) and racist (61%).

Uncertainty

about what constitutes “offensive” speech. As in the past, a majority

of Americans (60%) say “too many people are easily offended over the

language that others use.” Yet there is uncertainty about what

constitutes offensive speech: About half (51%) say it is easy to know

what others might find offensive, while nearly as many (48%) say it is

hard to know. In addition, majorities say that people in this country do

not generally agree about the types of language considered to be sexist

(65%) and racist (61%). Majority says social media companies have responsibility to remove “offensive” content. By a wide margin (66% to 32%), more people say social media companies have a responsibility to remove offensive content from their platforms than say they do not have this responsibility. But just 31% have a great deal or fair amount of confidence in these companies to determine what offensive content should be removed. And as noted, many Americans acknowledge it is difficult to know what others may find offensive.

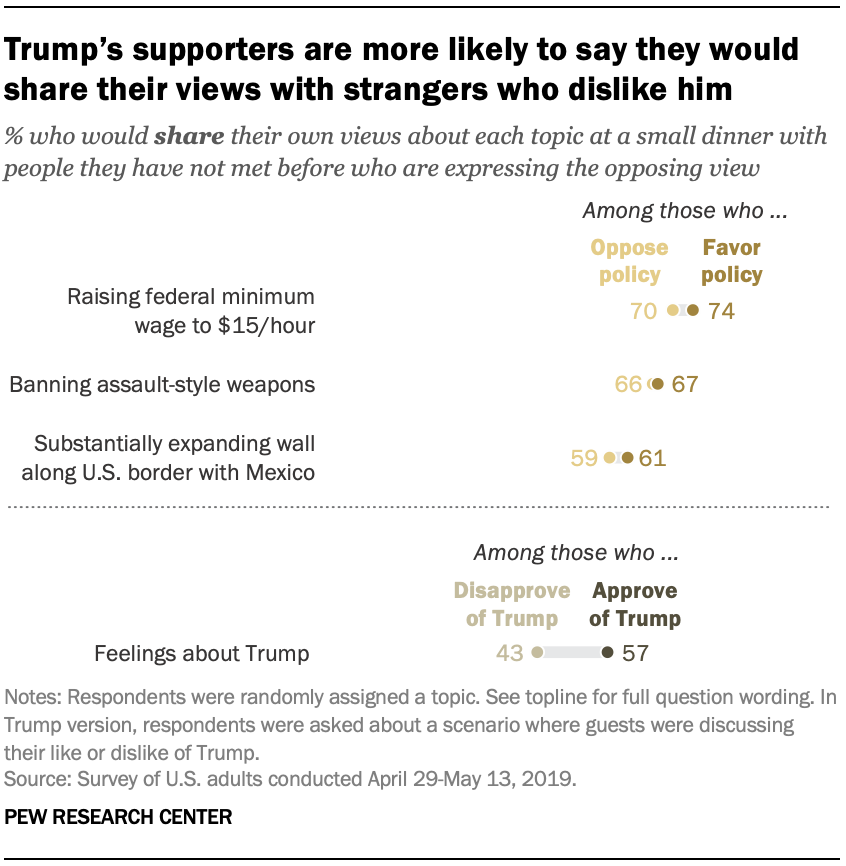

Talking about Trump with people who feel differently about him. The survey asks people to imagine attending a social gathering with people who have different viewpoints from theirs about the president. Nearly six-in-ten (57%) of those who approve of Trump’s job performance say they would share their views about Trump when talking with a group of people who do not like him. But fewer (43%) of those who disapprove of Trump say they would share their views when speaking with a group of Trump supporters.

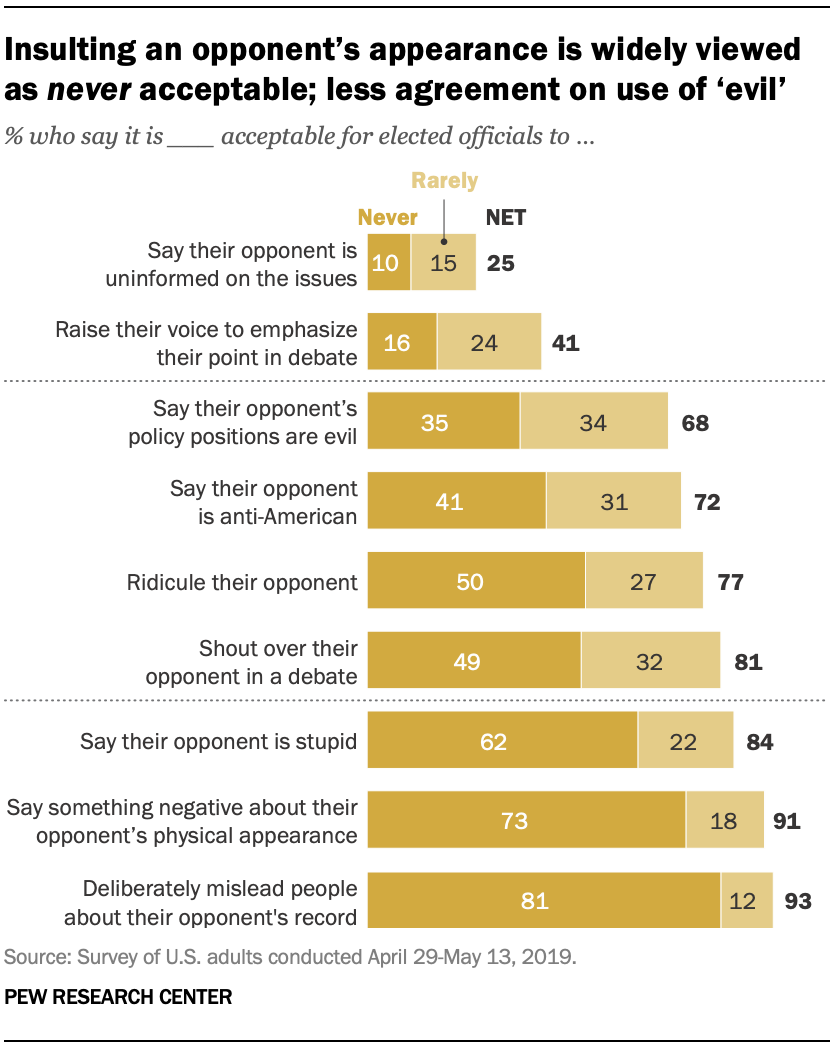

What’s OK – and off-limits – for political debates

While

Americans decry the tone of today’s political debates, they differ over

the kinds of speech that are acceptable – and off-limits – for elected

officials to use when criticizing their rivals.

While

Americans decry the tone of today’s political debates, they differ over

the kinds of speech that are acceptable – and off-limits – for elected

officials to use when criticizing their rivals. Some language and tactics are viewed as clearly over the line: A sizable majority (81%) says it is never acceptable for a politician to deliberately mislead people about their opponent’s record. There is much less agreement about the acceptability of elected officials using insults like “evil” or “anti-American.”

Partisanship has a major impact on these opinions. For the most part, Democrats are more likely than Republicans to say many of the insults and taunts are never acceptable. For example, 53% of Democrats say it is never acceptable for an elected official to say their opponent is anti-American; only about half as many Republicans (25%) say the same.

As with views of whether elected officials should “respect” their opponents, partisans hold the opposing side to a higher standard than their own side in views of acceptable discourse for political debates.

Most Republicans (72%) say it is never acceptable for a Democratic official to call a Republican opponent “stupid,” while far fewer (49%) say it is unacceptable for a Republican to use this slur against a Democrat. Among Democrats, 76% would rule out a Republican calling a Democratic opponent “stupid,” while 60% say the same about Democrat calling a Republican “stupid.” See Chapter 2 for an interactive illustration of how people’s views about the acceptability of political insults vary depending on whether or not they share the same party affiliation of the elected officials casting the insults.

Large shares have negative reactions to what Trump says

Majorities

of Americans say they often or sometimes feel a range of negative

sentiments – including concern, confusion, embarrassment and exhaustion –

about the things that Trump says.

Majorities

of Americans say they often or sometimes feel a range of negative

sentiments – including concern, confusion, embarrassment and exhaustion –

about the things that Trump says. Positive feelings about Trump’s comments are less widespread. Fewer than half say they often or sometimes feel informed, hopeful, excited and happy about what the president says. A 54% majority says they at least sometimes feel entertained by what Trump says, the highest percentage expressing a positive sentiment.

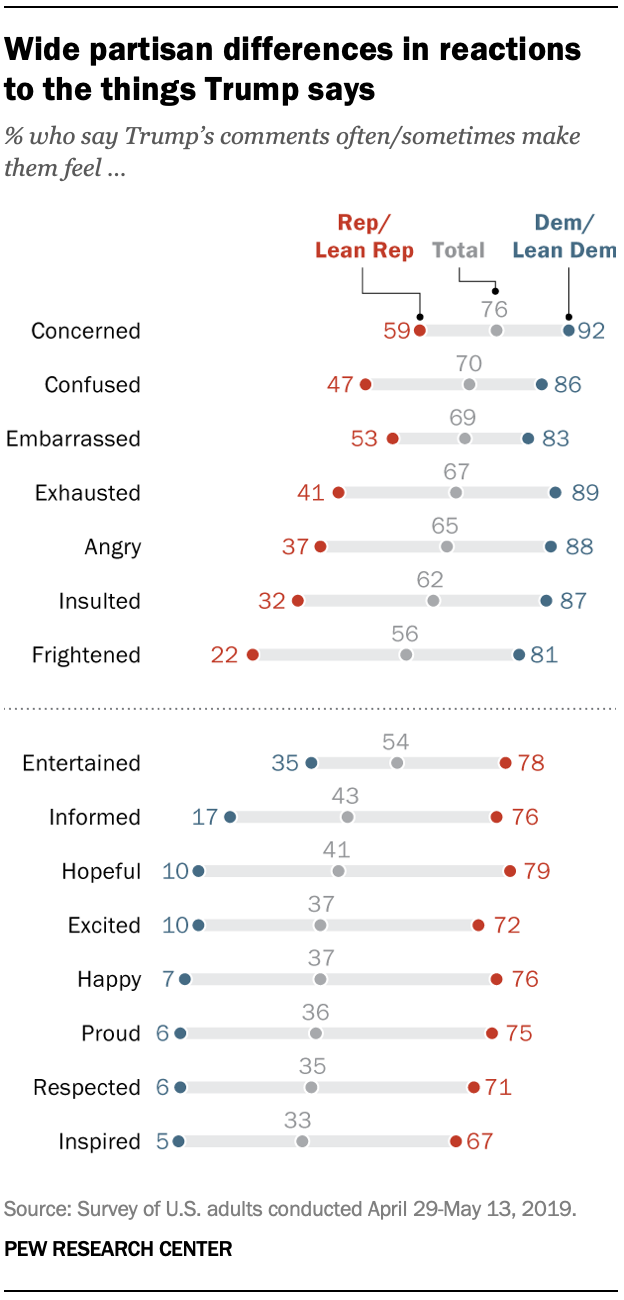

Democrats overwhelmingly have negative reactions to Trump’s statements, while the reactions of Republicans are more varied. Among Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, at least 80% say they often or sometimes experience each of the seven negative emotions included in the survey.

A 59% majority of Republicans and Republican leaners say they often or sometimes feel concerned by what Trump says. About half also say they are at least sometimes embarrassed (53%) and confused (47%) by Trump’s statements.

By contrast, large majorities of Republicans say they often or sometimes feel hopeful (79%), entertained (78%), informed and happy (76%) and other positive sentiments in response to the things Trump says.

No more than about 10% of Democrats express any positive feelings toward what Trump says, with two exceptions: 17% say they are often or sometimes informed, while 35% are at least sometimes entertained.

Republicans see a less ‘comfortable’ environment for GOP views

Republicans

say that members of their party across the country are less comfortable

than Democrats to “freely and openly” express their political views. In

addition, Republicans are far more critical than Democrats about the

climate for free expression in the nation’s educational institutions –

not just colleges, but also community colleges and K-12 public schools.

Republicans

say that members of their party across the country are less comfortable

than Democrats to “freely and openly” express their political views. In

addition, Republicans are far more critical than Democrats about the

climate for free expression in the nation’s educational institutions –

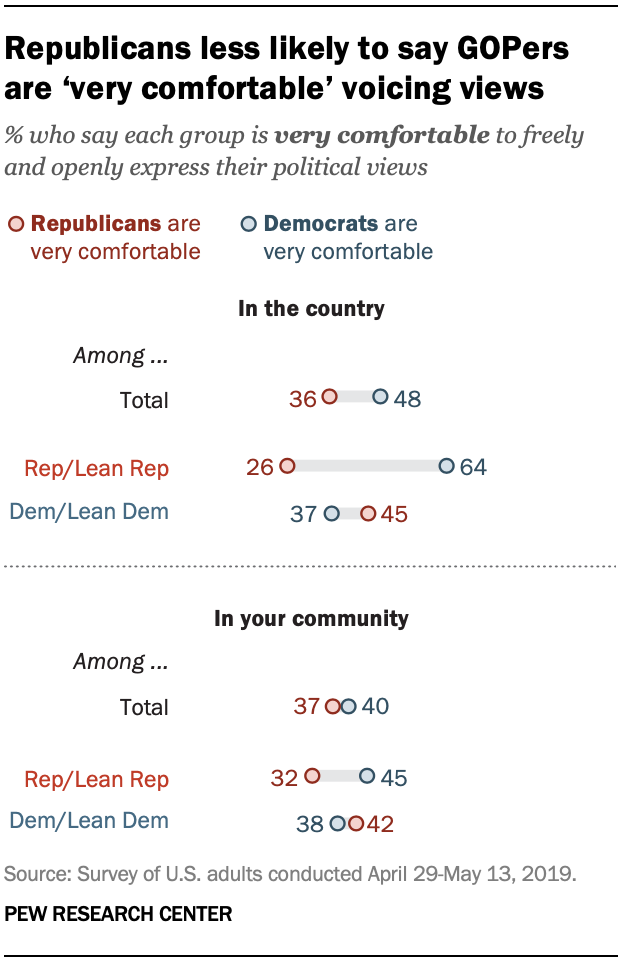

not just colleges, but also community colleges and K-12 public schools. Just 26% of Republicans say that Republicans across the country are very comfortable in freely and openly expressing their political opinions; nearly two-thirds of Republicans (64%) think Democrats are very comfortable voicing their opinions. Among Democrats, there are more modest differences in perceptions of the extent to which partisans are comfortable freely expressing their political views.

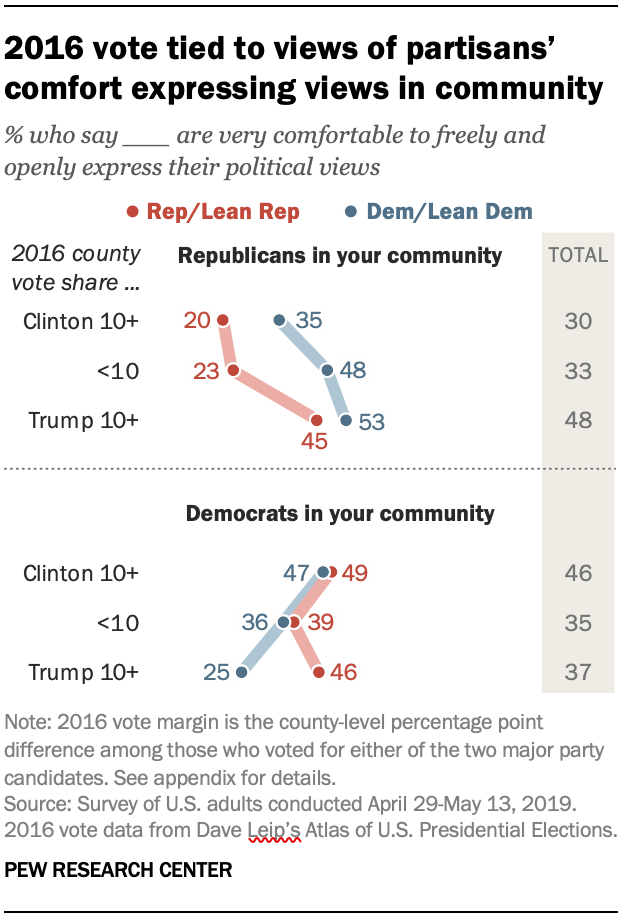

There are smaller partisan differences when it comes to opinions about how comfortable Republicans and Democrats are expressing their views in their local communities. Yet these opinions vary depending on the partisan composition of the local community. Republicans and Democrats living in counties that Trump won by wide margins in 2016 are more likely than those in evenly divided counties (or those that Hillary Clinton won decisively) to say Republicans are very comfortable expressing their views.

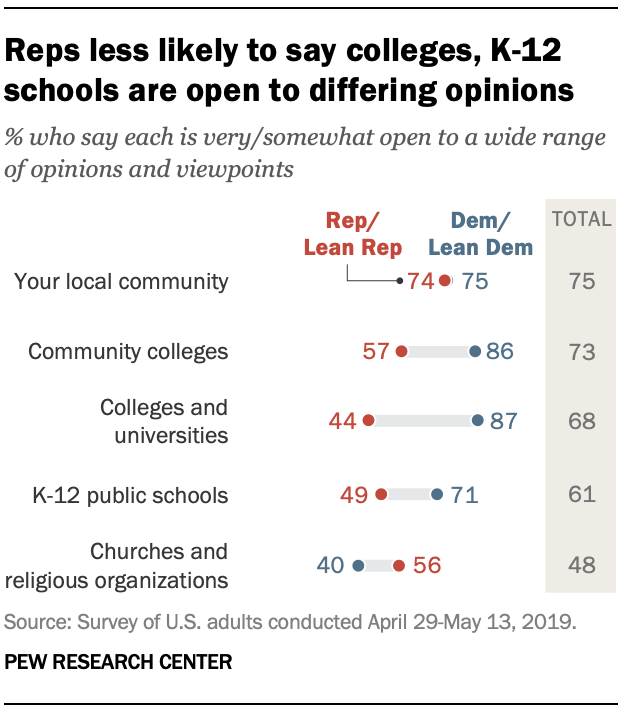

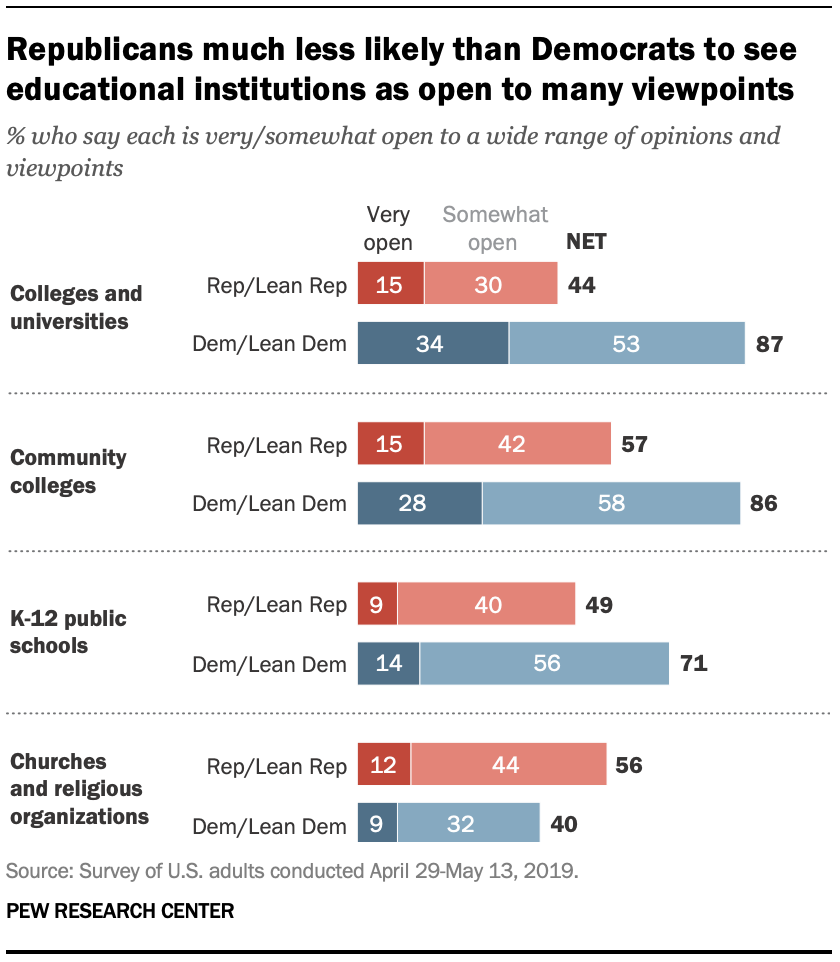

Republicans’ concerns about the climate for free speech on college campuses are not new.

The new survey finds that fewer than half of Republicans (44%) say

colleges and universities are open to a wide range of opinions and

viewpoints; Democrats are nearly twice as likely (87%) to say the same.

Republicans’ concerns about the climate for free speech on college campuses are not new.

The new survey finds that fewer than half of Republicans (44%) say

colleges and universities are open to a wide range of opinions and

viewpoints; Democrats are nearly twice as likely (87%) to say the same. Republicans also are less likely than Democrats to say community colleges and K-12 public schools are open to differing viewpoints. By contrast, a larger share of Republicans (56%) than Democrats (40%) say that churches and religious organizations are very or somewhat open to a wide range of opinions and viewpoints.

Members of both parties generally view their own local communities as places that are open to a wide range of viewpoints. Large and nearly identical shares in both parties say their local community is at least somewhat open to a wide range of opinions and viewpoints (75% of Democrats, 74% of Republicans).

The climate for discourse around the country, on campus and on social media

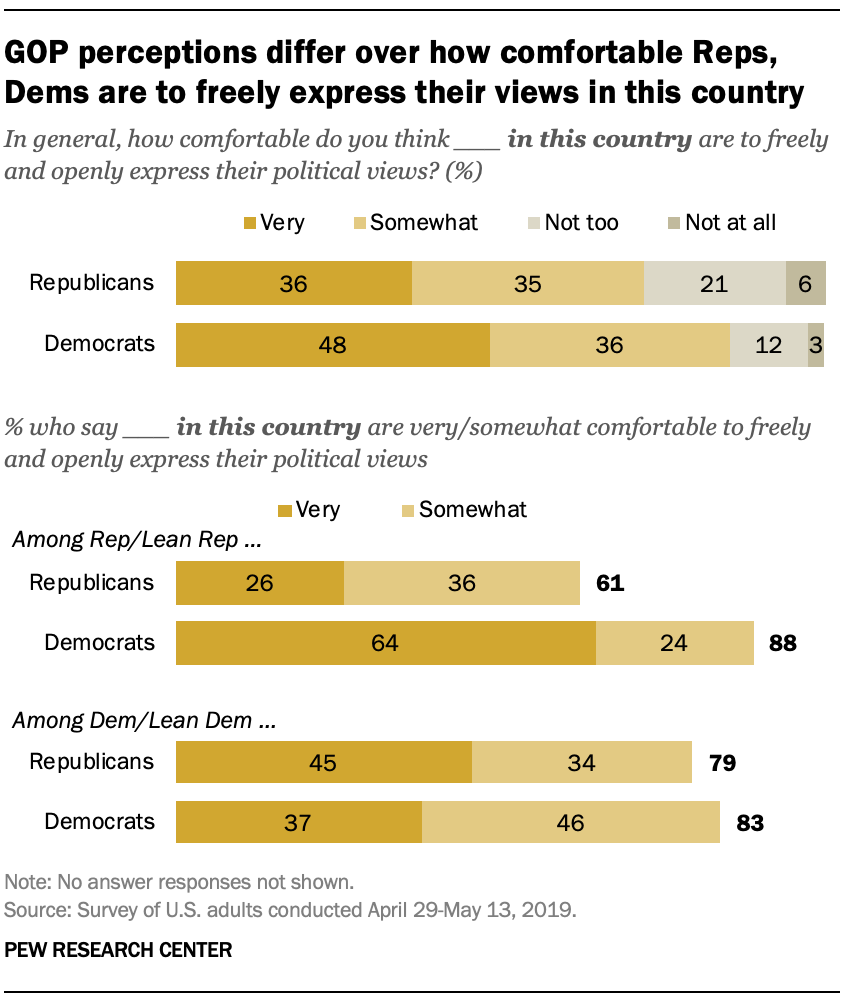

Seven-in-ten or more Americans say that Democrats, Republicans, liberals and conservatives are at least somewhat comfortable to “freely and openly express their political views” in both their local communities and in the country overall. But there are key partisan differences in these feelings – particularly in views of the national political climate, with Republicans especially likely to believe there is a more stifling environment around speech for Republicans than for Democrats.

Overall, Americans are more likely to see Democrats as comfortable expressing their views in this country than to say this about Republicans. While about half of the public (48%) says that Democrats in this country are “very comfortable” to freely and openly express their political views, a smaller share (36%) says the same about Republicans.

Republicans

and Republican-leaning independents are especially likely to feel that

Democrats and liberals are comfortable sharing their political views in

this country – and also to feel that Republicans are not. Nearly

nine-in-ten Republicans (88%) say Democrats are at least somewhat

comfortable openly sharing their views, with 64% saying that Democrats

in the country are “very comfortable” openly expressing their political

views. By comparison, only about a quarter (26%) say Republicans in the

country are very comfortable doing this (61% say Republicans are at

least somewhat comfortable doing this).

Republicans

and Republican-leaning independents are especially likely to feel that

Democrats and liberals are comfortable sharing their political views in

this country – and also to feel that Republicans are not. Nearly

nine-in-ten Republicans (88%) say Democrats are at least somewhat

comfortable openly sharing their views, with 64% saying that Democrats

in the country are “very comfortable” openly expressing their political

views. By comparison, only about a quarter (26%) say Republicans in the

country are very comfortable doing this (61% say Republicans are at

least somewhat comfortable doing this). By comparison, there are only modest differences in Democratic perceptions of partisans’ comfort with political expression in the country. Roughly eight-in-ten Democrats say Republicans are at least somewhat comfortable freely and openly expressing their opinions in this country – roughly the same share as say this about Democrats (79% and 83%, respectively).

While Democrats are slightly more likely to describe Republicans than Democrats as very comfortable to freely express their views (45% vs. 37%), the 8 percentage point gap in these perceptions is considerably narrower than the 38 point gap in GOP perceptions.

There are similar patterns in beliefs about liberals’ and conservatives’ comfort expressing their political views in the country. Overall, 83% of Americans say liberals in this country are at least somewhat comfortable freely and openly expressing their views, while 71% say this about conservatives. Democrats are modestly more likely to say conservatives are more comfortable than liberals with expressing their views (85% vs. 79%, respectively). By contrast, about nine-in-ten Republicans (91%) say liberals are at least somewhat comfortable freely expressing their views in this country, while 56% say conservatives are at least somewhat comfortable doing this.

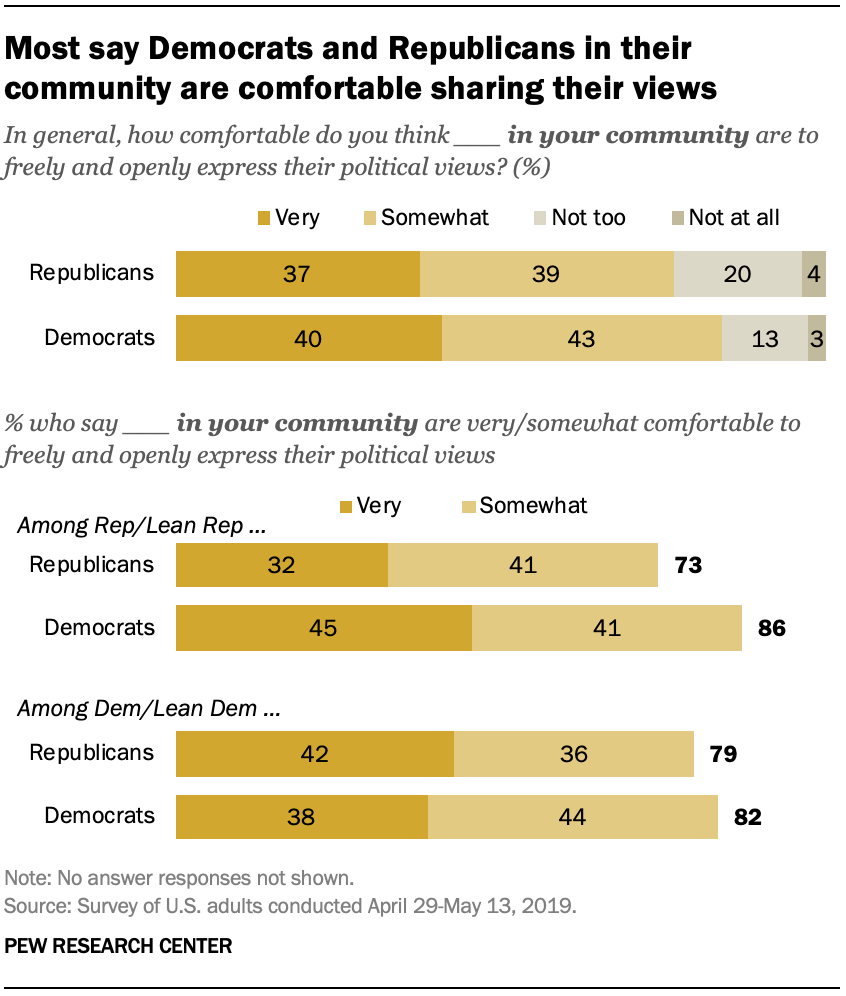

When asked about partisan groups in “your community,” roughly similar shares of Americans say Republicans (37%) and Democrats (40%) are very comfortable expressing their views.

Democrats

are about equally likely to say Republicans in their community and

Democrats in their community are comfortable to freely and openly

express their views: About eight-in-ten say both groups are somewhat

comfortable doing this, including about four-in-ten saying they are very

comfortable.

Democrats

are about equally likely to say Republicans in their community and

Democrats in their community are comfortable to freely and openly

express their views: About eight-in-ten say both groups are somewhat

comfortable doing this, including about four-in-ten saying they are very

comfortable. Republicans are more likely to say Democrats in their community are comfortable freely and openly expressing their political views than to say this about Republicans: 86% say Democrats are at least somewhat comfortable, while 73% say this about Republicans. However, this difference in perceptions about GOP comfort and Democratic comfort is considerably narrower at the community level than it is for the national environment.

How open people think their community is to Republicans and Democrats expressing their views depends on how red or blue it is

Perceptions of how comfortable partisans are expressing political views in their local communities vary by the political makeup of those communities. For example, 48% of adults who live in counties that Donald Trump carried by 10 points or more in the 2016 election say that Republicans in their local community are “very” comfortable expressing their political views; by contrast, just 30% of adults living in counties that Hillary Clinton won by similar margins say Republicans in their community are very comfortable freely and openly expressing their political views.

An

opposite – though somewhat less pronounced – pattern is seen in views

of Democrats’ comfort expressing their political views: 46% of adults

living in counties that Clinton won by 10 points or more say Democrats

in their communities are very comfortable expressing their political

views; 37% of adults living in counties that Trump won by 10 or more

points say this.

An

opposite – though somewhat less pronounced – pattern is seen in views

of Democrats’ comfort expressing their political views: 46% of adults

living in counties that Clinton won by 10 points or more say Democrats

in their communities are very comfortable expressing their political

views; 37% of adults living in counties that Trump won by 10 or more

points say this. When it comes to Republicans’ comfort of political expression in their communities, both Democrats and Republicans see greater Republican comfort in counties Trump carried by 10 points or more than in counties where the election was closely contested or where Clinton won by at least 10 points.

This same dynamic is present in Democrats’ views of how comfortable Democrats in their communities are to freely and openly express their views (as the Clinton share of the 2016 vote rises, Democrats’ perceptions of the comfort Democrats feel expressing their views increases).

But Republican views of how comfortable Democrats are sharing their political views do not follow this pattern. About equal shares of Republicans who live in solid Clinton counties (49%) and solid Trump counties (46%) say they think Democrats in their community feel very comfortable sharing their political views.

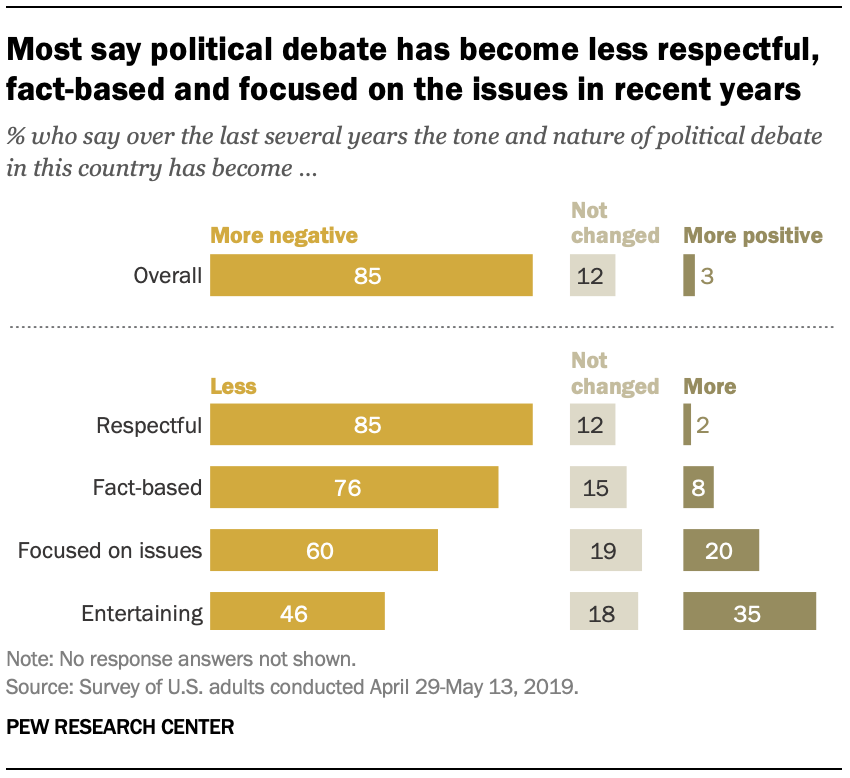

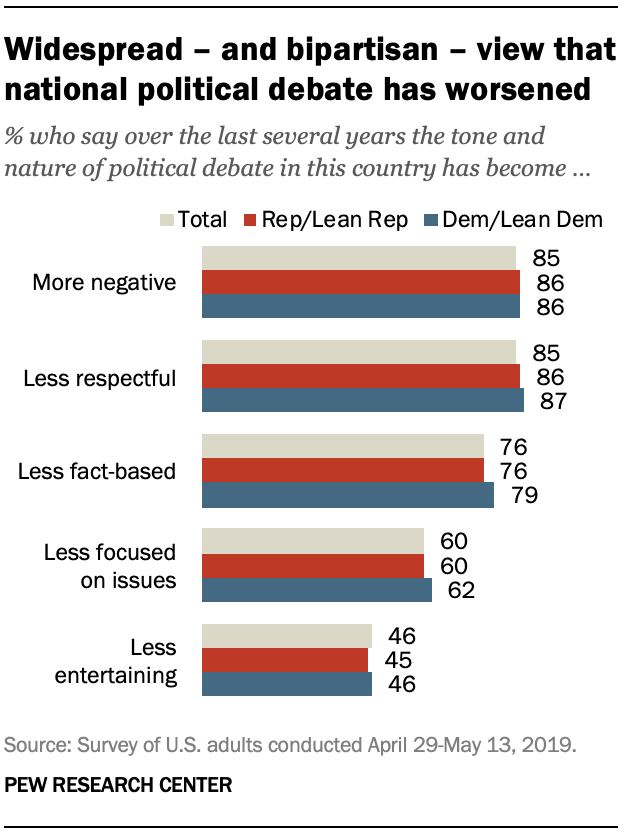

Public sees a deterioration in the tone of national political debate

Overwhelming majorities of the public say that the tone and nature of political debate in the country has become more negative (85%), less respectful (85%) and less fact-based (76%) over the last several years. And six-in-ten say the debate has been less focused on issues than in the past.

Few Americans say there has been positive movement on any of these dimensions over the last several years – just 3% say the tone of national political debate has become more positive, while 2% say it has become more respectful, 8% say more fact-based and 20% say it has become more focused on issues.

About a third of the public (35%) says that the tone of politics has become more entertaining in recent years. Still, nearly half (46%) say it has become less entertaining over this period.

Partisans offer similar evaluations of the current state of political debate in the country. For instance, 86% of both Republicans and Democrats say the tone of political debate has become more negative in recent years, while about six-in-ten in both groups say political debate has become less focused on issues (60% of Republicans, 62% of Democrats). Those who discuss politics more frequently – in both partisan groups – are somewhat more likely than others to view a decline in national political discourse.

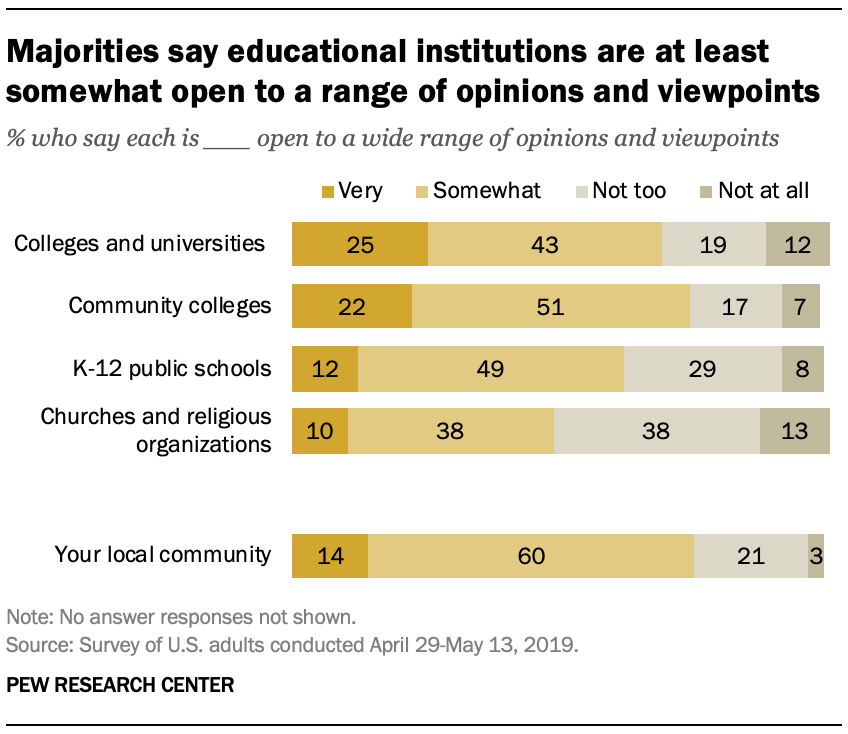

Wide partisan differences in views of how open educational institutions, religious organizations are to a ‘wide range of opinions and viewpoints’

Roughly

two-thirds of Americans (68%) say colleges and universities are very or

somewhat open to “a wide range of opinions and viewpoints,” while a

slightly larger majority (73%) say the same about community colleges.

About six-in-ten (61%) view K-12 public schools as at least somewhat

open to different views, while about half (48%) describe churches and

religious organizations this way.

Roughly

two-thirds of Americans (68%) say colleges and universities are very or

somewhat open to “a wide range of opinions and viewpoints,” while a

slightly larger majority (73%) say the same about community colleges.

About six-in-ten (61%) view K-12 public schools as at least somewhat

open to different views, while about half (48%) describe churches and

religious organizations this way. Three-quarters (75%) say their own local community is very or somewhat open to a wide range of opinions and viewpoints.

However, relatively small shares describe any of these places or institutions as “very” open – a quarter (25%) say this about colleges and universities, while roughly the same share (22%) says this about community colleges; 14% describe their own community this way. About one-in-ten say K-12 public schools (12%) and churches and religious organizations (10%) are very open to many different views.

There are wide partisan differences in these views – particularly in assessments of the openness of postsecondary educational institutions. Nearly nine-in-ten Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (87%) describe colleges and universities as at least somewhat open to a wide range of opinions and viewpoints – including 34% who say these institutions are very open. By comparison, just 44% of Republicans and Republican leaners say colleges and universities are either very (15%) or somewhat (30%) open in this way (roughly a quarter say colleges and universities are “not at all” open to viewpoint diversity).

The

partisan gap is smaller, though still substantial, in evaluations of

community colleges. About six-in-ten Republicans (57%) say community

colleges are very or somewhat open to many different opinions and

viewpoints, while almost nine-in-ten Democrats (86%) say this.

The

partisan gap is smaller, though still substantial, in evaluations of

community colleges. About six-in-ten Republicans (57%) say community

colleges are very or somewhat open to many different opinions and

viewpoints, while almost nine-in-ten Democrats (86%) say this. The partisan gap seen in assessments of educational institutions extends to views of primary and secondary public schools as well. While about seven-in-ten Democrats (71%) describe K-12 public schools as at least somewhat open to differences in opinions and viewpoints, roughly half of Republicans (49%) say the same.

In contrast, Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say churches and religious organizations are open to a range of opinions and viewpoints. A 56% majority of Republicans say this, compared with just 40% of Democrats.

When it comes to their local communities, partisans are in general agreement – about three-quarters of both Republicans (74%) and Democrats (75%) say their local communities are at least somewhat open to a wide range of opinions and viewpoints.

Overall, women (73%) are more likely than men (63%) to say colleges and universities are at least somewhat open. And while just 57% of Americans ages 65 and older say these institutions are at least somewhat open, fully seven-in-ten (71%) of Americans under 65 say this.

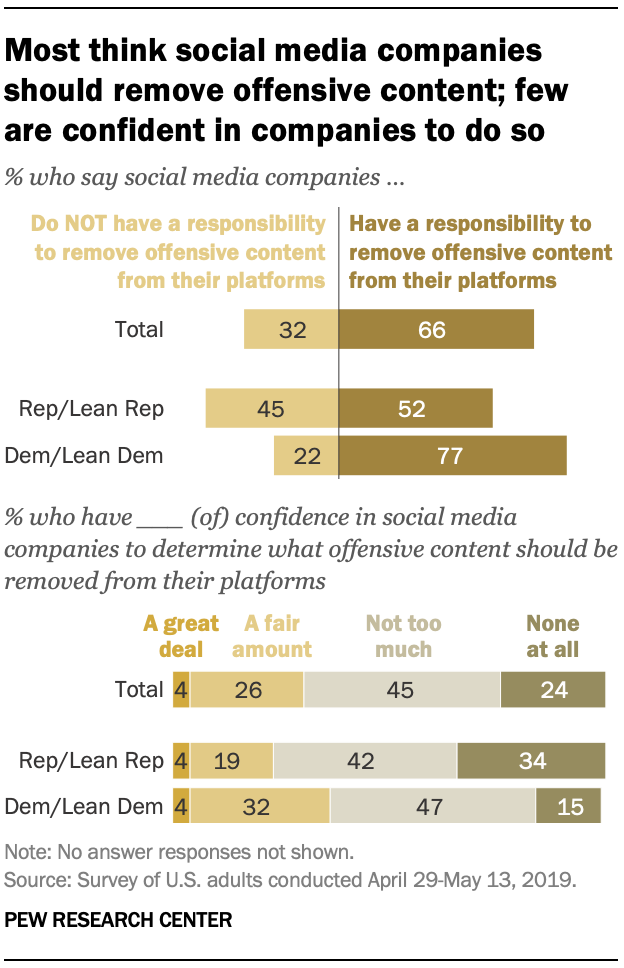

Most say social media companies should remove offensive content, but fewer are confident in them to determine what should be removed

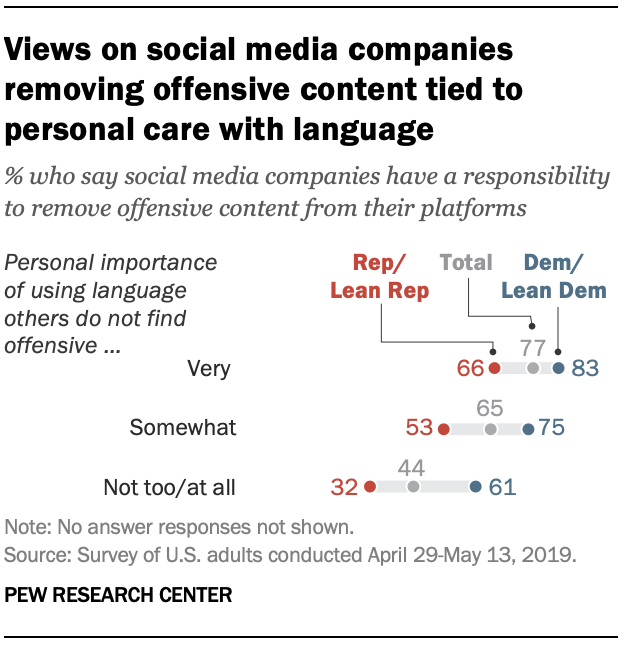

Amid public debate about how social media companies should handle controversial content, about two-thirds of Americans (66%) say these companies have a responsibility to remove offensive content from their platforms; 32% say they do not have this responsibility.

While

majorities in both parties say social media companies should remove

offensive content from their platforms, this view is more widely held by

Democrats than Republicans: About three-quarters of Democrats (77%) say

this, compared with 52% of Republicans and Republican leaners.

While

majorities in both parties say social media companies should remove

offensive content from their platforms, this view is more widely held by

Democrats than Republicans: About three-quarters of Democrats (77%) say

this, compared with 52% of Republicans and Republican leaners. Yet the public does not have very much confidence in social media companies to determine what offensive content should be removed from their platforms.

About three-in-ten Americans (31%) have at least a fair amount of confidence in social media companies to decide which content to remove – including just 4% who say they have a great deal of confidence in these companies to do this.

Among Republicans, 23% have confidence in social media companies to determine what content should be removed; far greater shares say they have not too much (42%) or no confidence at all (34%) in companies to make this determination.

Democrats also largely lack confidence in social media companies to determine what content should be removed, though they are somewhat more likely than Republicans to express at least a fair amount of confidence (37%).

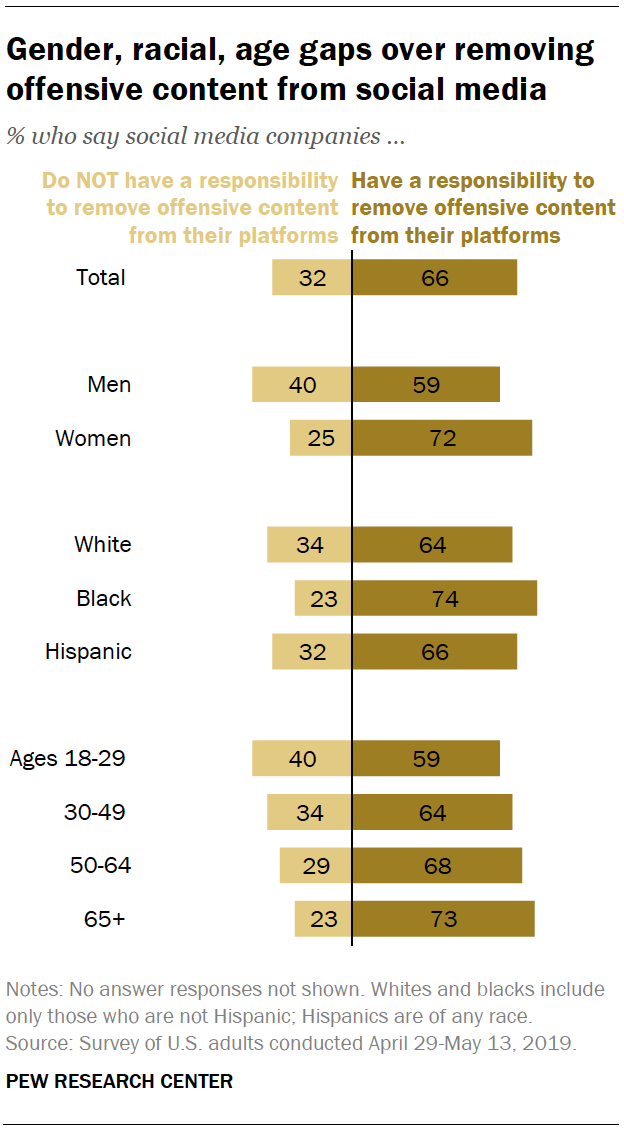

While majorities across demographic groups say social media companies have a responsibility to remove offensive content from their platforms, there remain gender, age and racial differences in the shares who express this view.

Overall,

women (72%) are more likely than men (59%) to say social media

companies have this responsibility, and gender differences are in

evident in both parties.

Overall,

women (72%) are more likely than men (59%) to say social media

companies have this responsibility, and gender differences are in

evident in both parties. About six-in-ten Republican women (62%) say this, compared with about four-in-ten Republican men (43%). And Democratic women (79%) are modestly more likely than Democratic men (73%) to say social media companies have this responsibility.

Blacks (74%) are more likely than whites (64%) and Hispanics (66%) to say social media companies should remove offensive content.

Older adults are also more likely than younger adults to say companies have this responsibility: About seven-in-ten of those older than 65 (73%) say social media companies should remove such content; by comparison, 59% of 18- to 29-year-olds say this.

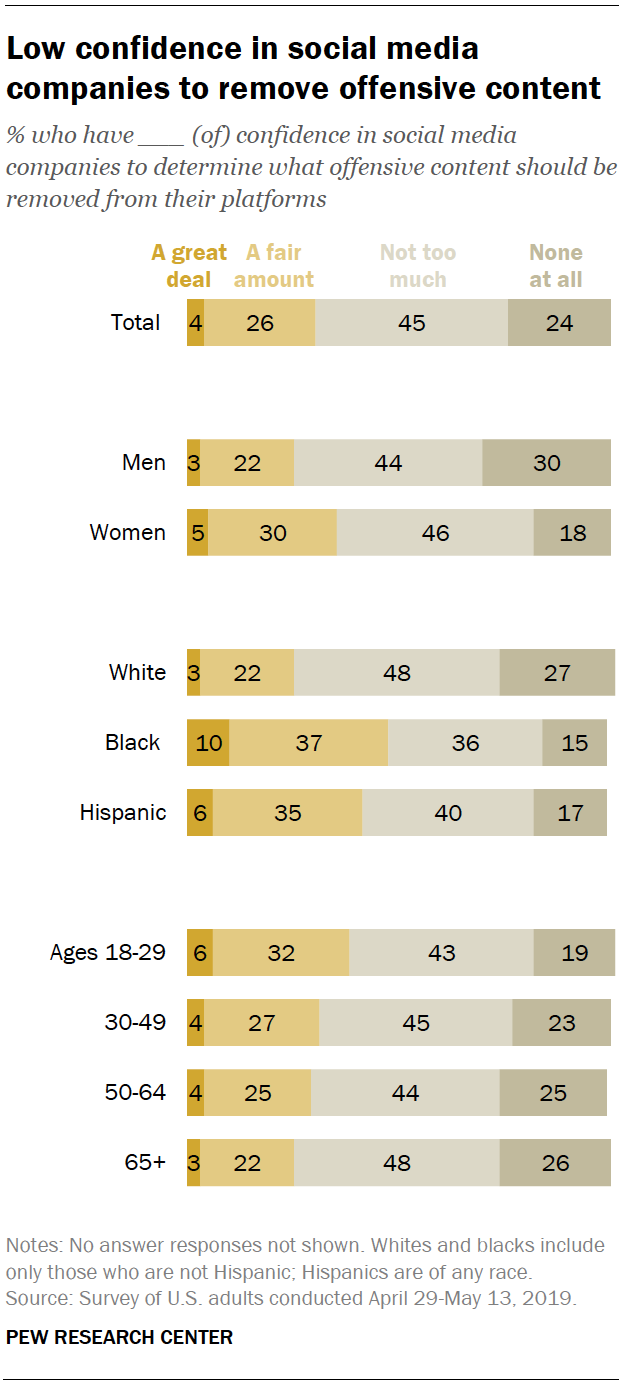

Women – who are more likely than men to say social media companies should remove offensive content – also have more confidence than men in these companies’ abilities to determine what content should be removed. Overall, 36% of women, compared with 25% of men, say they have at least a fair amount of confidence in companies to do this.

About

half (48%) of black people express at least a fair amount of confidence

in social media companies to determine what content should be removed,

compared with just a quarter of whites. Four-in-ten Hispanics say they

have at least a fair amount of confidence in companies to make this

determination.

About

half (48%) of black people express at least a fair amount of confidence

in social media companies to determine what content should be removed,

compared with just a quarter of whites. Four-in-ten Hispanics say they

have at least a fair amount of confidence in companies to make this

determination. Although the youngest Americans are less likely than the oldest Americans to say social media companies have a responsibility to remove offensive content, they have more confidence than older Americans in these companies’ abilities to determine what content should be removed. Nearly four-in-ten 18- to 29-year-olds (38%) have a fair amount or great deal of confidence in social media companies to determine what content should be removed from their platforms, compared with just 24% of those ages 65 and older.

Those who find it important for them personally to use language that other people do not find offensive are more likely to say that social media companies have a responsibility to remove offensive content from their platforms.

Among those who say it is very important for them personally to use language that doesn’t offend others, about three-quarters (77%) say social media companies are responsible for removing offensive content.

But

among Americans who say it is not too or not at all important for them

personally to use inoffensive language, fewer than half (44%) say social

media companies have this responsibility.

But

among Americans who say it is not too or not at all important for them

personally to use inoffensive language, fewer than half (44%) say social

media companies have this responsibility. The pattern holds within party, particularly among Republicans. Two-thirds of Republicans who say it is very important that they don’t offend others say social media companies should remove offensive content. By contrast, a much smaller share of Republicans (32%) who place lower importance on using inoffensive language say social media companies should remove such content.

Among Democrats, 83% of those who say it is very important that their language doesn’t offend others say social media companies have a responsibility to remove offensive content; a smaller majority (61%) of those who place little or no importance on using inoffensive language say the same.

The bounds of political debate and criticism

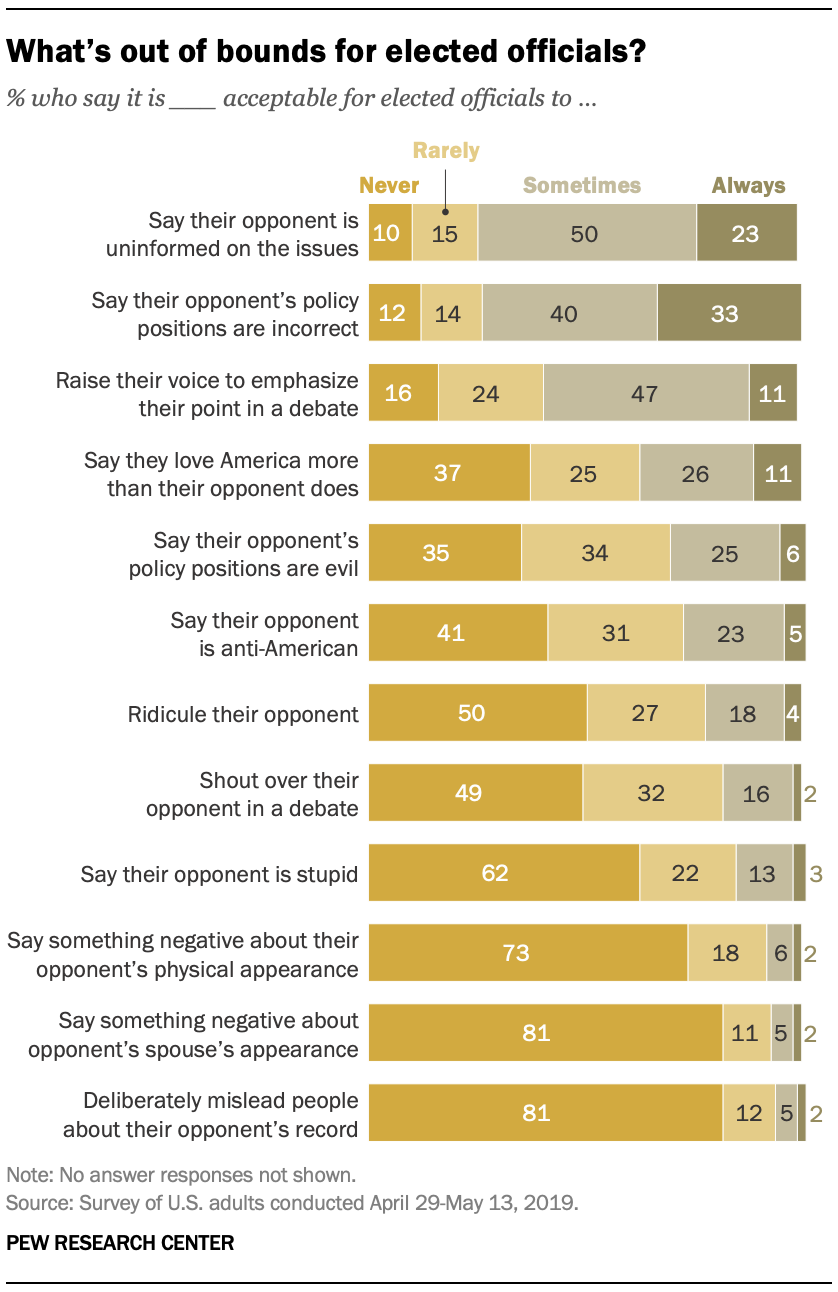

The public draws distinctions when it comes to the types of speech and behavior they deem acceptable from elected officials. Wide majorities of Americans say it is acceptable for elected officials to call their opponent uninformed on the issues and to raise their voice in a debate, but there is much lower tolerance for officials personally mocking their opponents or deliberately mischaracterizing their record.

Roughly

three-quarters of Americans say it is at least sometimes acceptable to

say their opponent’s policy positions are incorrect (73%) or that their

opponent is uninformed on the issues (74%). A narrow majority (58%) says

it is at least sometimes acceptable for elected officials to raise

their voice in a debate. Few see these behaviors as never acceptable.

Roughly

three-quarters of Americans say it is at least sometimes acceptable to

say their opponent’s policy positions are incorrect (73%) or that their

opponent is uninformed on the issues (74%). A narrow majority (58%) says

it is at least sometimes acceptable for elected officials to raise

their voice in a debate. Few see these behaviors as never acceptable. But there are behaviors that overwhelming majorities say have no place in political discourse. About eight-in-ten (81%) say it is never acceptable to deliberately mislead people about an opponent’s record or to say something negative about the physical appearance of an opponent’s spouse (81%), while 73% say it is never acceptable to criticize their opponent’s appearance – and nine-in-ten or more consider these behaviors at most rarely acceptable.

The public also generally views calling one’s political opponent “stupid” as out of bounds: 62% say this is never acceptable, while an additional 22% say it is rarely acceptable. And about half of the public says it is never acceptable for an official to shout over their opponent in a debate (49%) or to ridicule an opponent (50%), with three-quarters or more saying these behaviors are no more than rarely acceptable.

However, public opinion is more mixed over the acceptability of calling an opponent’s policy positions “evil” – while 35% say this is never acceptable and 34% say it is rarely acceptable, 31% say it is at least sometimes acceptable. Similarly, while 41% believe that it is never acceptable for an elected official to say their opponent is “anti-American,” 31% say this is rarely acceptable and 27% say this is at least sometimes acceptable.

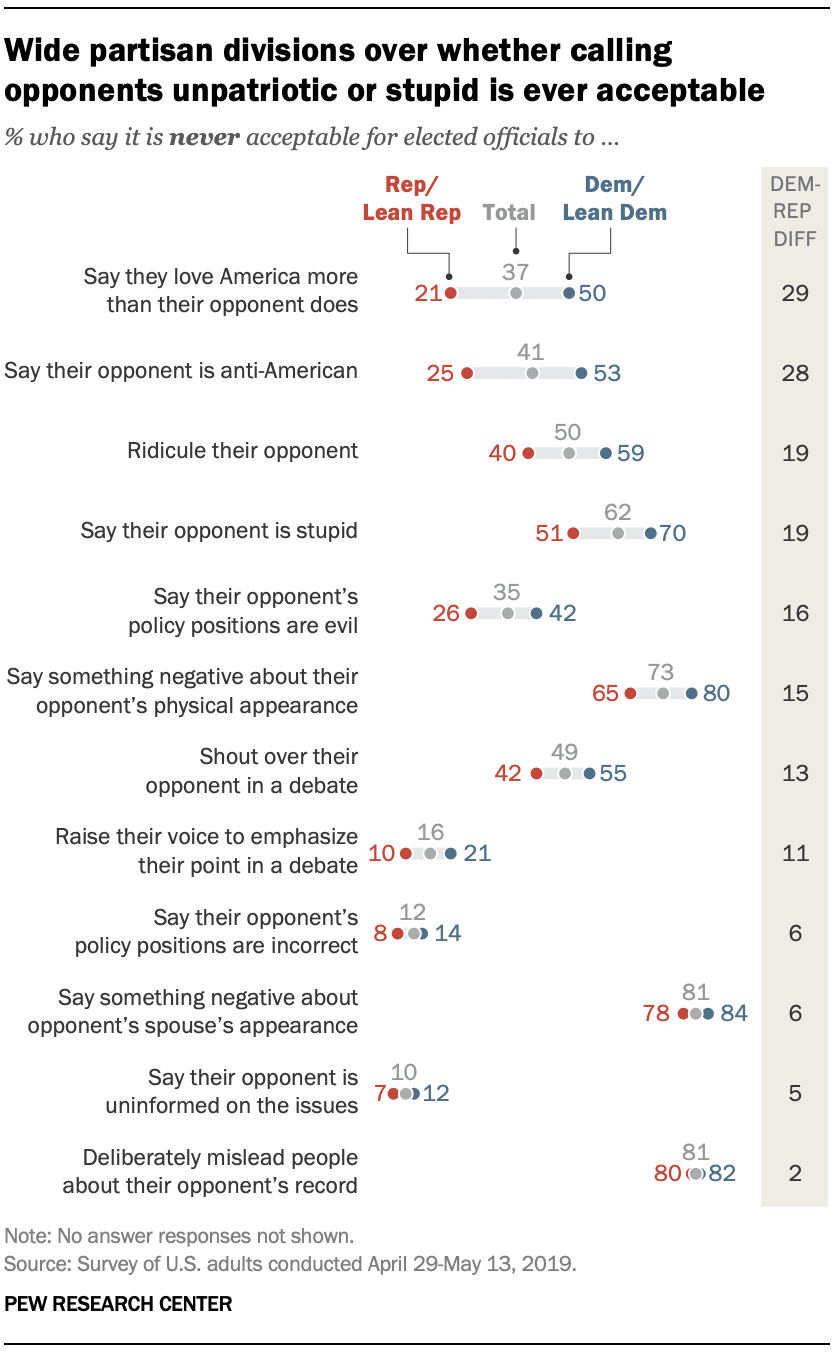

Partisans differ over acceptability of some types of political criticism

Democrats

are more likely than Republicans to view a range of behaviors as out of

bounds. And some of the largest partisan gaps are over whether it is

acceptable for elected officials to call into question the patriotism of

their political opponents.

Democrats

are more likely than Republicans to view a range of behaviors as out of

bounds. And some of the largest partisan gaps are over whether it is

acceptable for elected officials to call into question the patriotism of

their political opponents. About three-quarters of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (76%) say it is rarely or never acceptable for an elected official to say “they love America more than their opponent does,” including half who say this is never acceptable.

By comparison, 45% of Republicans and Republican leaners say it is rarely or never acceptable for an official to say they love America more than their opponent – including just 21% who consider this completely out of bounds in politics. The pattern of opinion about whether it is acceptable to call one’s opponent anti-American is nearly identical.

There also are substantial partisan gaps in other areas, including the acceptability of ridiculing one’s opponent (59% of Democrats say this is never acceptable vs. 40% of Republicans), calling them stupid (70% vs. 51%) or saying their policy positions are evil (42% vs. 26%). But Democrats and Republicans are in general agreement that deliberately misleading people about their opponent’s record is out of bounds (82% of Democrats and 80% of Republicans say this is never acceptable), as is criticism of a spouse’s appearance (84% of Democrats, 78% of Republicans say it’s never acceptable).

Insults are seen as more acceptable when your party is the instigator

Partisans also have different views of how acceptable these types of political insults are, depending on the partisanship of the political officials involved.

Trump’s impact on the tone of political debate, important characteristics for elected officials

A majority of Americans say that Donald Trump has had a negative impact on the tone of political debate in the United States.

A majority of Americans say that Donald Trump has had a negative impact on the tone of political debate in the United States. Overall, 55% say that Trump has changed the tone and nature of political debate in the U.S. for the worse since entering politics; fewer than half as many (24%) say he has changed it for the better, and 20% say he has not changed it much either way.

Democrats overwhelmingly say Trump has changed the tone of political debate for the worse. More than eight-in-ten Democrats and Democratic leaners (84%) say Trump has had a negative effect on political debate in this country, including 92% of liberal Democrats and 78% of conservative and moderate Democrats.

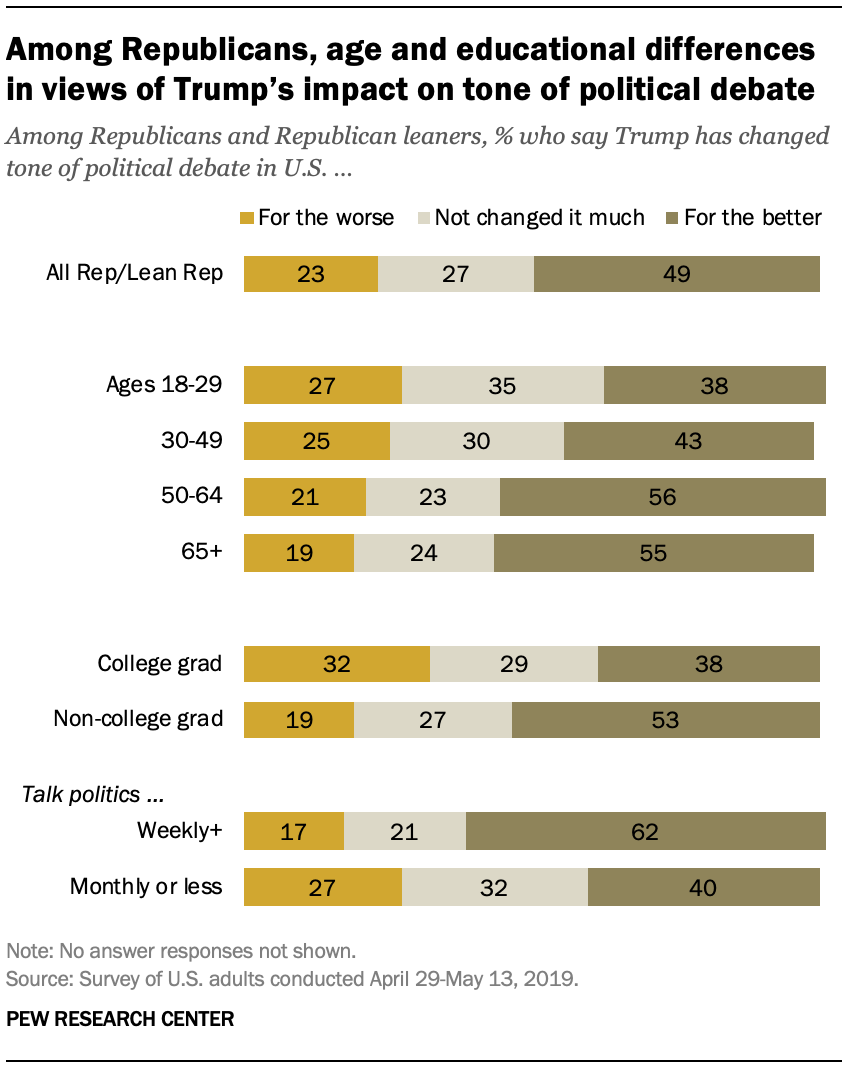

Republicans and Republican leaners are more divided in their views: 49% say Trump has changed the tone of the debate for the better, while 23% say he has changed it for the worse and 27% say he hasn’t changed it much either way. A majority of conservative Republicans (58%) think Trump has changed the tone of political debate for the better, compared with 35% of moderate and liberal Republicans.

Aside from the partisan differences on this question, there are significant divides by age and education. Those with higher levels of education are much more likely than those with lower levels to say that Trump has changed the tone of political debate for the worse. For instance, 73% of postgraduates say this compared with 47% of those with no college experience.

And adults younger than 50 (59%) are more likely than those 50 and older (51%) to say that Trump’s impact on the tone of political debate in the U.S. has been negative.

The differences among Republicans over Trump’s impact on the tone of political debate extend beyond ideology.

The differences among Republicans over Trump’s impact on the tone of political debate extend beyond ideology. Among Republicans and Republican leaners, older adults and those without a college degree are significantly more likely than younger adults and those with a college degree to say Trump has changed the tone of political debate in the country for the better.

In addition, Republicans who say they talk about politics with others at least weekly are much more likely than those who talk politics less often to say Trump’s impact on debate has been a positive one (62% vs. 40%).

Majorities say Trump’s comments elicit concern, exhaustion, confusion

When

asked about their reactions to the things Trump says, the public

reports experiencing negative reactions more frequently than positive

ones.

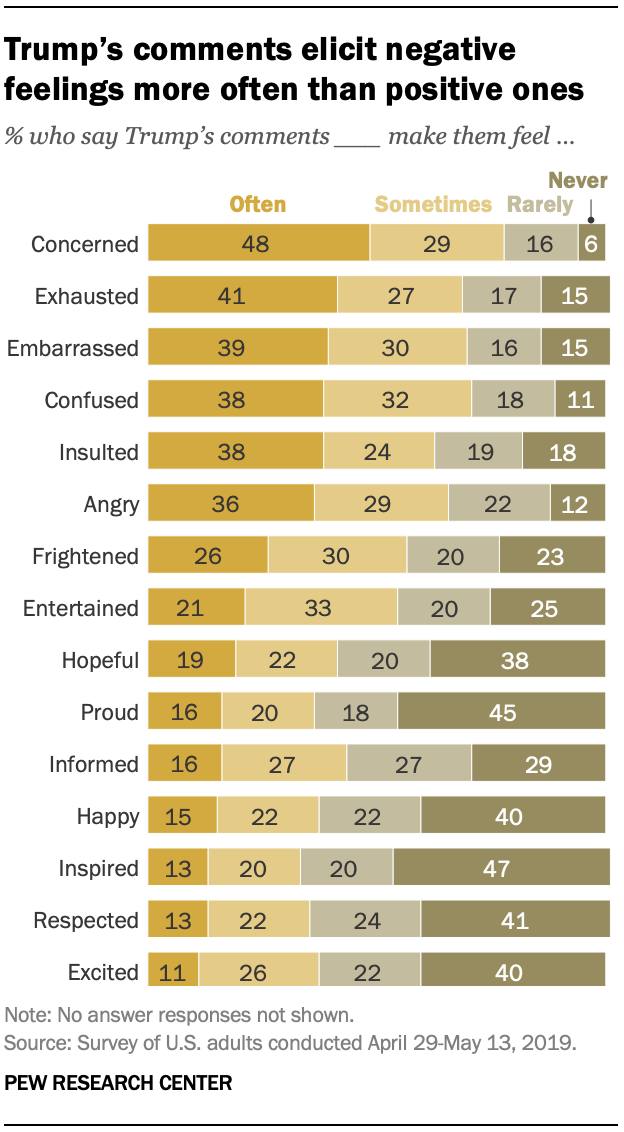

When

asked about their reactions to the things Trump says, the public

reports experiencing negative reactions more frequently than positive

ones. Out of a list of 15 possible reactions, “concerned” is the most frequently reported reaction to Trump’s comments. Overall, 76% say Trump’s comments often (48%) or sometimes (29%) make them feel concerned. Relatively few say Trump’s comments rarely (16%) or never (6%) make them feel concerned.

Other negative emotions also are widely experienced in response to Trump’s comments, including confusion (70% say this happens often or sometimes), embarrassment (69%), exhaustion (67%) and anger (65%).

Feeling entertained is the most frequent positive reaction to Trump’s comments: 54% say they often (21%) or sometimes (33%) feel entertained by what Trump says.

Fewer than half say Trump’s rhetoric at least sometimes makes them feel informed (43%), hopeful (41%), happy (37%), proud (36%) and other positive sentiments.

Large

majorities of Democrats and Democratic leaners report that Trump’s

comments at least sometimes make them feel each of the seven negative

emotions asked about in the survey. For example, 92% say they often or

sometimes feel concerned by what Trump says and 89% often or sometimes

feel exhausted by his rhetoric.

Large

majorities of Democrats and Democratic leaners report that Trump’s

comments at least sometimes make them feel each of the seven negative

emotions asked about in the survey. For example, 92% say they often or

sometimes feel concerned by what Trump says and 89% often or sometimes

feel exhausted by his rhetoric. Conversely, majorities of Republicans and Republican leaners say they at least sometimes experience each of the eight positive emotions included in the survey in response to the things Trump says.

However, emotional reactions to Trump’s rhetoric among Republicans and Democrats are not entirely parallel, with Democrats somewhat more likely to say they have negative reactions than Republicans are to say they have positive ones.

For instance, across the seven negative items, an average of 87% of Democrats say they often or sometimes feel this way because of Trump’s comments. Across the eight positive items, an average of 74% of Republicans say they often or sometimes feel this.

In addition, significant shares of Republicans say Trump’s comments make them feel negative emotions, at least sometimes. Overall, 59% of Republicans say the things Trump says often or sometimes make them feel concerned, 53% say his comments make them feel embarrassed and 47% say they feel confused. About a third of Republicans (32%) say they feel insulted by Trump’s rhetoric, at least sometimes.

By contrast, relatively small shares of Democrats report feeling positive emotions in reaction to what Trump says. While 35% of Democrats say Trump’s comments often or sometimes make them feel entertained, fewer than two-in-ten say they often or sometimes experience any of the other positive emotions.

Public says elected officials should avoid use of heated language

Americans

believe there is a link between elected officials’ use of heated or

aggressive rhetoric and the possibility of violence against people and

groups, and there is broad agreement that officials should avoid this

type of language.

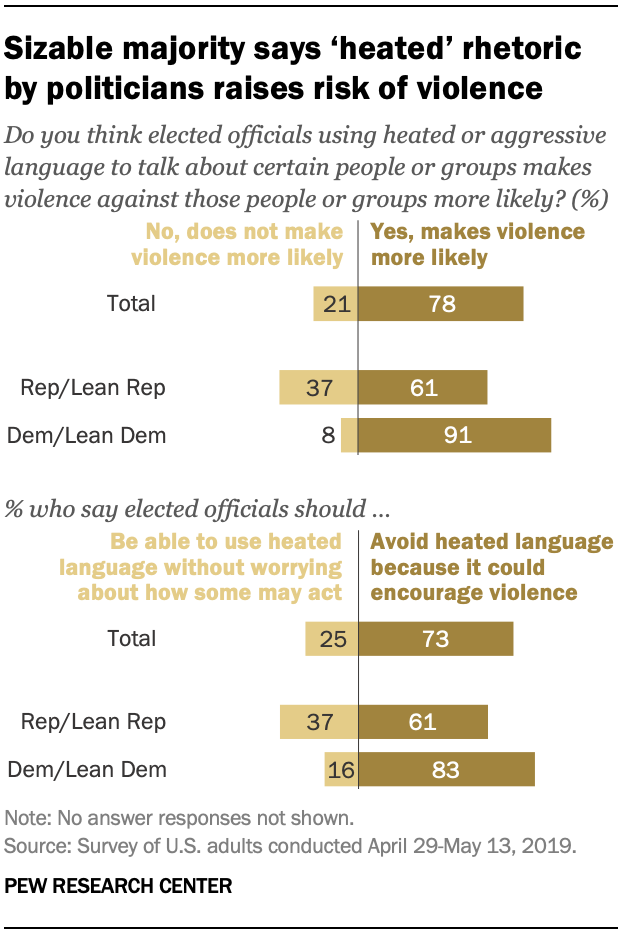

Americans

believe there is a link between elected officials’ use of heated or

aggressive rhetoric and the possibility of violence against people and

groups, and there is broad agreement that officials should avoid this

type of language. About eight-in-ten (78%) say that elected officials using heated or aggressive language to talk about certain people or groups makes violence against those people or groups more likely; far fewer (21%) say this type of language does not make violence more likely.

Majorities in both parties say there is a connection between the language officials use to talk about certain groups and the possibility of violence, but this view is more widely held among Democrats and Democratic leaners (91%) than among Republicans and Republican leaners (61%).

Consistent with this view, 73% of the public says elected officials should avoid heated or aggressive language because it could encourage some people to take violent action; 25% say that elected officials should be able to use heated or aggressive language to express themselves without worrying about whether some people may act on what they say. Among Democrats, 83% say elected officials should avoid the use of heated language because of the possibility that it could encourage violence; a narrower majority of Republicans (61%) also take this view.

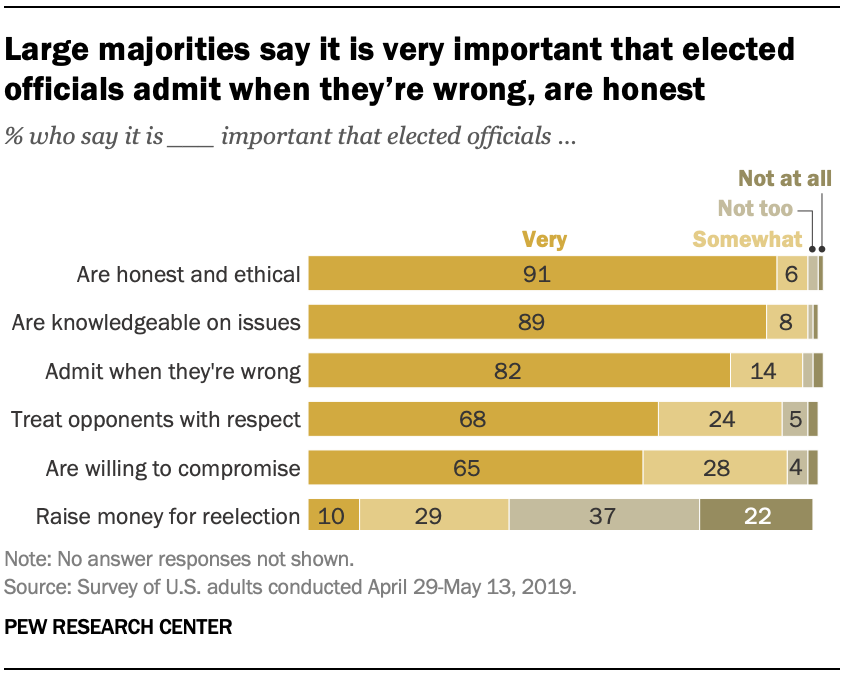

Honesty, knowledge highly valued in elected officials; narrower majorities say respect, willingness to compromise are very important

There

is widespread agreement among the public that it is very important for

elected officials to be honest and ethical (91%), to be knowledgeable on

the issues (89%) and to admit when they are wrong (82%).

There

is widespread agreement among the public that it is very important for

elected officials to be honest and ethical (91%), to be knowledgeable on

the issues (89%) and to admit when they are wrong (82%). Roughly two-thirds say it is very important for elected officials to treat opponents with respect (68%) and to be willing to compromise with them (65%).

Among six traits included in the survey, only one – spending time raising money for reelection – is not identified as a valued trait for elected officials. Just 10% say it is very important that elected officials spend time raising money for reelection; 29% say this is somewhat important while a majority (59%) say this is not too or not at all important.

Some traits, such as honesty, are seen as universally important for elected officials across different contexts. However, views of the importance of other traits – notably, willingness to compromise with opponents and treating them with respect – vary depending on one’s own partisan affiliation and the party of the elected official.

Among

Americans overall, 68% say it is very important for elected officials

to treat their political opponents with respect. Democrats (72%) are

somewhat more likely than Republicans (63%) to highly value politicians

treating opponents with respect. Similarly, there is a modest partisan

divide between the shares of Democrats (69%) and Republicans (61%) who

say it is very important for elected officials to be willing to

compromise with their political opponents.

Among

Americans overall, 68% say it is very important for elected officials

to treat their political opponents with respect. Democrats (72%) are

somewhat more likely than Republicans (63%) to highly value politicians

treating opponents with respect. Similarly, there is a modest partisan

divide between the shares of Democrats (69%) and Republicans (61%) who

say it is very important for elected officials to be willing to

compromise with their political opponents. There are much more pronounced partisan gaps when respondents are asked specifically about Republican and Democratic elected officials.

Both Republicans and Democrats are far more likely to say it’s very important for the other party’s elected officials to be willing to compromise and to treat opponents with respect than it is for their own party’s elected officials to behave this way.

Nearly eight-in-ten Democrats say it is very important for Republican elected officials to be willing to compromise with Democrats (79%) and to treat Democratic elected officials with respect (78%). However, far fewer value these behaviors when asked about their own party’s elected officials: Just 48% of Democrats say it is very important for Democratic elected officials to be willing to compromise with Republicans, and 47% say the same about Democratic officials treating Republican officials with respect.

A similar dynamic is seen among Republicans. While 78% of Republicans say it is very important for Democratic elected officials to be willing to compromise with Republicans, only 41% feel it is very important for members of their own party be open to compromise with Democrats. Similarly, Republicans are far more likely to say Democratic officials should treat their Republican opponents with respect (75%) than to say Republican elected officials should be respectful toward their Democratic opponents (49%).

The public’s level of comfort talking politics and Trump

Americans are much more cautious about talking politics with others than discussing a range of other subjects, including the weather and sports.

Comfort with talking about the weather is near universal: 95% of the public says that they would be either very (74%) or somewhat (22%) comfortable talking about the weather with someone they don’t know well. Sizable majorities also say they would be very or somewhat comfortable talking about movies and television (90%), the economy (77%) and sports (69%).

The

public is less comfortable talking about politics, religion and Donald

Trump. Overall, 55% say they would feel at least somewhat comfortable

talking about Trump with someone they do not know well; just 25% say

they would feel very comfortable doing this. Public comfort talking

about religion is similar: 60% would be at least somewhat comfortable

discussing this subject, but only about a quarter (24%) would feel very

comfortable.

The

public is less comfortable talking about politics, religion and Donald

Trump. Overall, 55% say they would feel at least somewhat comfortable

talking about Trump with someone they do not know well; just 25% say

they would feel very comfortable doing this. Public comfort talking

about religion is similar: 60% would be at least somewhat comfortable

discussing this subject, but only about a quarter (24%) would feel very

comfortable. Talking politics ranks even lower on the public’s comfort list. Just 17% say they would be very comfortable talking politics with someone they don’t know well; another 35% say they would feel somewhat comfortable.

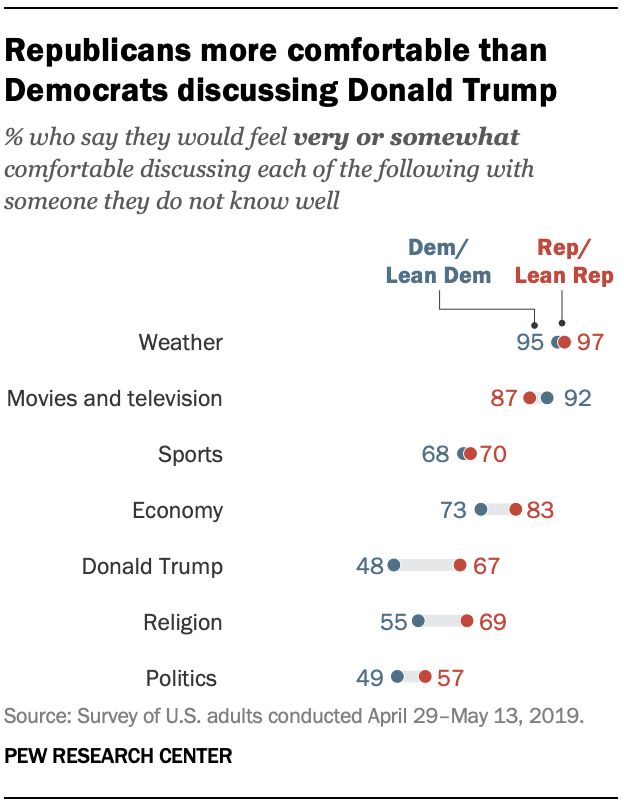

Partisans

express similar levels of comfort discussing topics like the weather,

sports and entertainment, but Republicans are more likely than Democrats

to say they are comfortable talking about Donald Trump, the economy and

religion.

Partisans

express similar levels of comfort discussing topics like the weather,

sports and entertainment, but Republicans are more likely than Democrats

to say they are comfortable talking about Donald Trump, the economy and

religion. Two-thirds of Republicans and Republican leaners (67%) say they would be very or somewhat comfortable talking about Trump with someone they don’t know well, while only about half of Democrats and Democratic leaners (48%) say this.

Republicans also are more likely than Democrats to say they would feel comfortable talking about the economy (83% vs. 73%), religion (69% vs. 55%) and politics (57% vs. 49%).

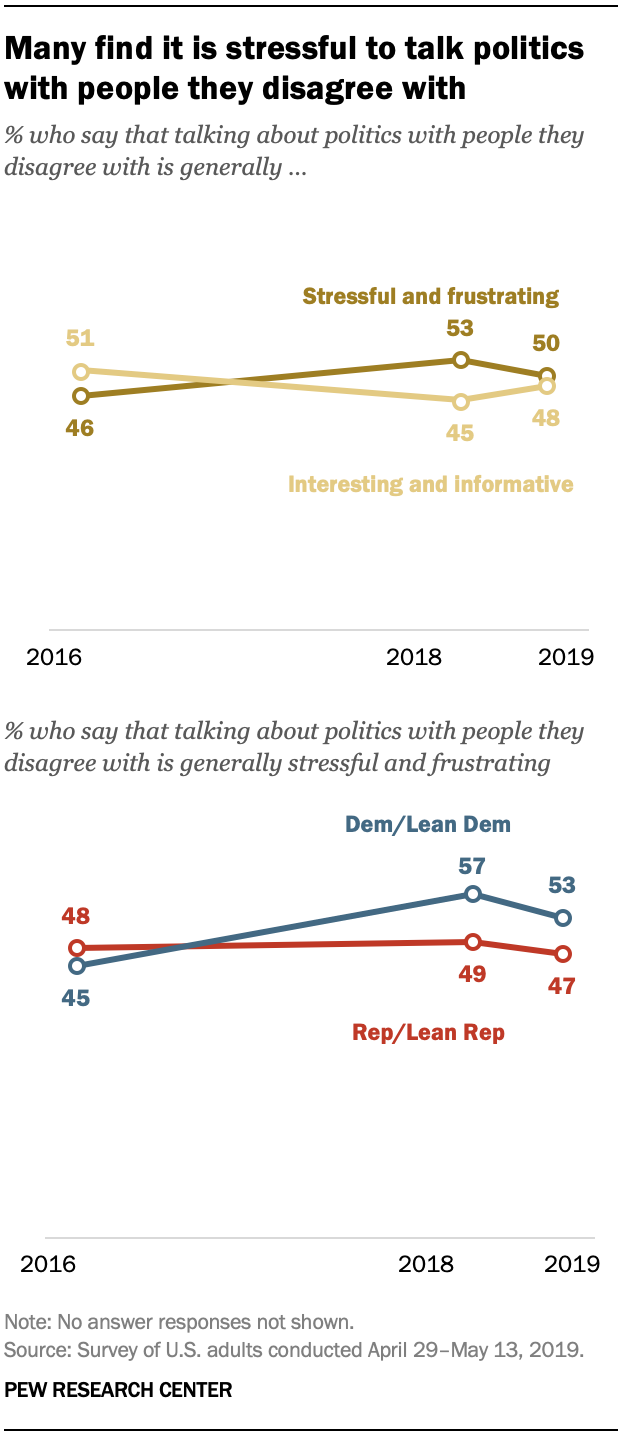

Half say it is stressful to talk politics with people they disagree with

When

it comes to political conversations with those they disagree with, the

public is split in their reactions: Half say talking politics with

people they disagree with is generally stressful and frustrating, while

about as many (48%) say it is interesting and informative.

When

it comes to political conversations with those they disagree with, the

public is split in their reactions: Half say talking politics with

people they disagree with is generally stressful and frustrating, while

about as many (48%) say it is interesting and informative. Democrats and Democratic leaners (53%) are slightly more likely than Republicans and Republican leaners (47%) to say political conversations with people they disagree with are stressful and frustrating. The share of Democrats who find these conversations stressful is higher than it was in the spring of 2016 – prior to Donald Trump’s election – when 45% said this. Views among Republicans have changed little over the past several years.

Liberal Democrats are especially likely to say they find political conversations with people they disagree with frustrating: 63% say this, compared with 44% of conservative and moderate Democrats.

There also is an ideological divide in these views among Republicans: Conservatives (52%) are more likely than moderates and liberals (39%) to find talking politics with people they disagree with to be stressful and frustrating.

Offering your views on politics – and Trump – over dinner

When asked to think about being at a small dinner with strangers who disagree with them about Donald Trump, Americans who approve of his job performance are more likely to say they would share their own views about him than are those who disapprove.

Nearly

six-in-ten adults who approve of Donald Trump’s job performance (57%)

say they would share their views about the president at a small dinner

where the other guests are talking about how they really dislike Trump.

Only about four-in-ten of those who disapprove of Trump (43%) say they

would be likely to share their views in a scenario where people at the

table were talking about how they really like Trump.

Nearly

six-in-ten adults who approve of Donald Trump’s job performance (57%)

say they would share their views about the president at a small dinner

where the other guests are talking about how they really dislike Trump.

Only about four-in-ten of those who disapprove of Trump (43%) say they

would be likely to share their views in a scenario where people at the

table were talking about how they really like Trump. Similar dinner party scenarios were asked about for three other political topics (note: each respondent was only asked about one scenario). However, for these other topics – minimum wage, gun policy and a border wall with Mexico – there is no gap by issue position in the shares who would volunteer their views. For instance, 74% of those who favor raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour and 70% who oppose this say they would voice their opinions to a group of dining companions who are expressing views opposite to their own.

In addition, for all three issue areas, clear majorities – regardless of their stance on the topic – say they would express their views at the dinner.

A survey experiment: Sharing political views with strangers who disagree

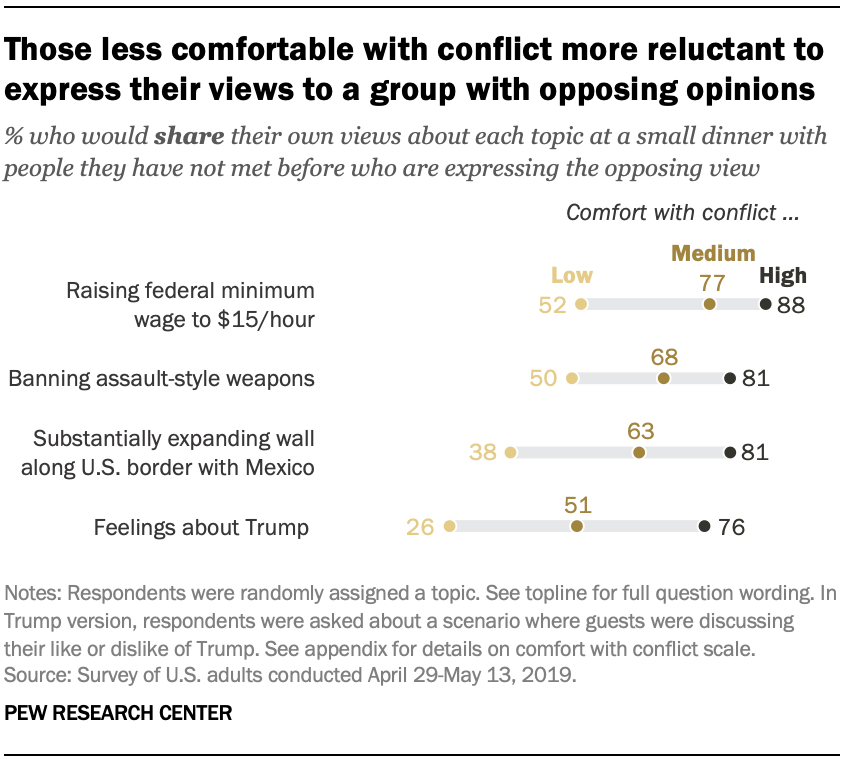

Comfort

with conflict is strongly associated with people’s willingness to

express their opposing views about Trump and other political topics in a

dinner party setting (see appendix for more details on the comfort with

conflict scale).

Comfort

with conflict is strongly associated with people’s willingness to

express their opposing views about Trump and other political topics in a

dinner party setting (see appendix for more details on the comfort with

conflict scale). Only about a quarter (26%) of those who score low on a three-question scale measuring comfort with conflict would share their views about Trump over dinner with people who disagree with them. By contrast, 51% of those who fall in the middle of the scale and 76% of those who have high comfort with conflict say they would share their own views about Trump with a group of dinner companions who are expressing the opposing view.

The association between comfort with conflict and willingness to share your own views in a small dinner setting holds across the three other issue areas, though it is especially pronounced in the scenario about views of Trump.

Trump is a particularly difficult dinner conversation topic for those who are least comfortable with conflict: Among those with low comfort with conflict, just 26% would share their views about Trump to a table taking the opposing position. By comparison, 38% of those with low conflict comfort would share their views on the border wall, while about half would share their views about assault-style weapons (50%) or the federal minimum wage (52%). Among those who are most comfortable with conflict, there are more modest differences in willingness to share views in each of these scenarios.

People’s willingness to share their views about Trump varies depending on the partisan makeup of the places where they live.

Trump

approvers who live in counties that Trump won by wide margins over

Hillary Clinton in 2016 are more likely than Trump approvers who live in

more politically mixed places or in counties that Clinton won by wide

margins to say they would share their views over dinner with a group of

people who don’t like the president. There is a similar – but inverse –

pattern in the willingness of those who disapprove of Trump to speak up

among a group of people who like Trump.

Trump

approvers who live in counties that Trump won by wide margins over

Hillary Clinton in 2016 are more likely than Trump approvers who live in

more politically mixed places or in counties that Clinton won by wide

margins to say they would share their views over dinner with a group of

people who don’t like the president. There is a similar – but inverse –

pattern in the willingness of those who disapprove of Trump to speak up

among a group of people who like Trump. About six-in-ten Trump approvers living in counties that Trump won by 10 percentage points or more in 2016 (62%) say they would share their views about the president at a small dinner where people at the table are having a conversation about how they really dislike Trump. By comparison, about half of Trump approvers who live in places where the election was decided by less than 10 points (53%) or in places that Clinton won by more than 10 points (49%) say they would share their views in this situation.

This general pattern also is seen among those who disapprove of Trump: 49% of Trump disapprovers who live in counties Clinton won by at least 10 points would share their views of the president at a small dinner where people at the table are having a conversation about how much they like Trump, while 38% of disapprovers who live in counties that were decided by less than 10 points and 39% of disapprovers who live in counties that Trump won by at least 10 points say they would share their own views.

As a result, in counties that Trump won by 10 percentage points or more, there is a 23 percentage point gap between the share of Trump approvers (62%) and disapprovers (39%) who would express their views of the president at a dinner with those who disagree with them. By comparison, in counties that Clinton won by at least 10 points, Trump approvers (49%) and Trump disapprovers (47%) are about equally likely to say they would share their views if they were in this situation.

Why would you participate in – or avoid – contentious discussions about Trump?

When those who say they would share their views at a small dinner with people whose views of the president differ from their own are asked why they would share, about four-in-ten Trump disapprovers (39%) and a similar share of Trump approvers (35%) say they would do so because it’s important to for others to know where they stand.

Strongly

held views about the president are also mentioned by sizable shares in

both groups as a reason they would speak up, though Trump approvers are

more likely than disapprovers to say this: 34% of Trump approvers who

would share their views in these circumstances cite positive views or

praise of Trump as the reason why they would participate in the

conversation, while about a quarter of Trump disapprovers who would do

so (24%) mention deeply negative or strong criticism of Trump as a

reason.

Strongly

held views about the president are also mentioned by sizable shares in

both groups as a reason they would speak up, though Trump approvers are

more likely than disapprovers to say this: 34% of Trump approvers who

would share their views in these circumstances cite positive views or

praise of Trump as the reason why they would participate in the

conversation, while about a quarter of Trump disapprovers who would do

so (24%) mention deeply negative or strong criticism of Trump as a

reason. Among those who would share their views, 25% of Trump disapprovers and 15% of Trump approvers explain that they would do so because the conversation might be productive.

Relatively few people who would engage in a conversation about Trump with people who have a different view of him than they do would do so in the expectation that they could change others’ minds about him (10% of disapprovers and 14% of approvers who say they would share their views cite this as a reason).

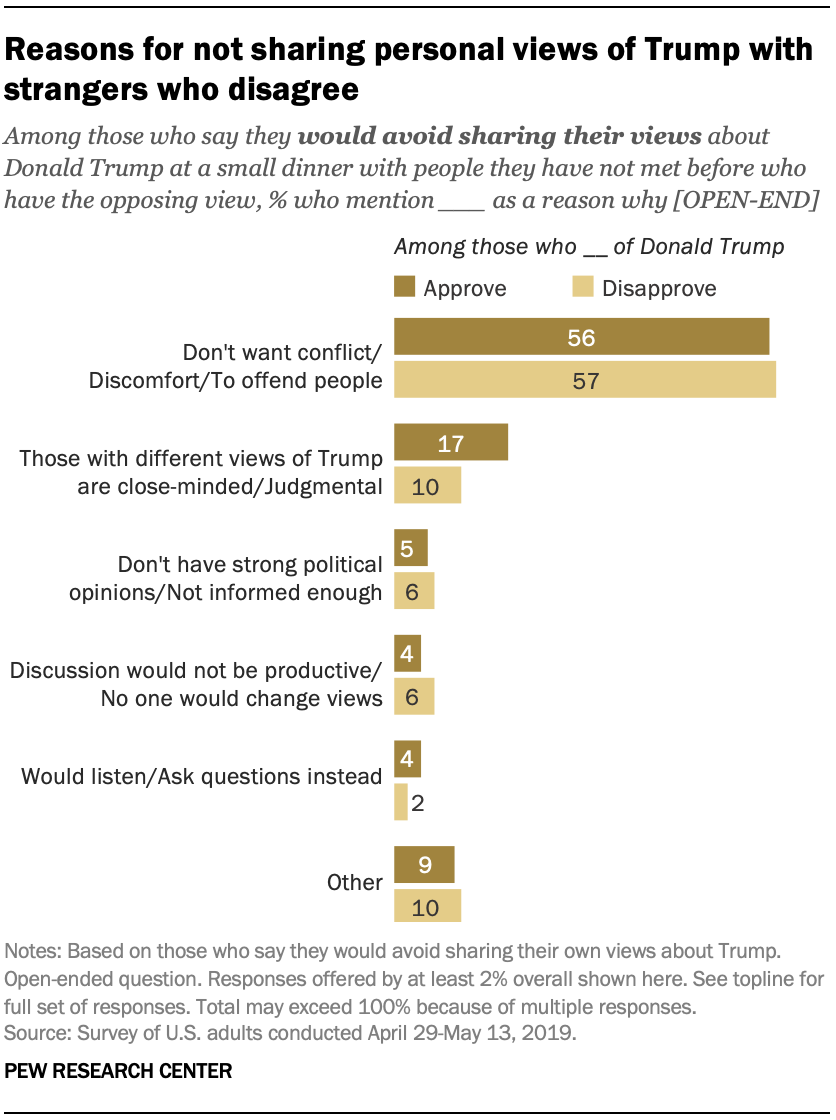

The

most common reasons given for not sharing personal views of Trump at a

dinner with strangers who feel differently is a desire to avoid

confrontation or discomfort: More than half of those who say they would

avoid sharing their views about Trump mention something along these

lines as a reason why, with similar shares of Trump approvers (56%) and

disapprovers (57%) saying this.

The

most common reasons given for not sharing personal views of Trump at a

dinner with strangers who feel differently is a desire to avoid

confrontation or discomfort: More than half of those who say they would

avoid sharing their views about Trump mention something along these

lines as a reason why, with similar shares of Trump approvers (56%) and

disapprovers (57%) saying this. Though less common a response, 10% of Trump disapprovers who would not share their views and 17% of approvers who would not share their views cite a criticism of those who have different opinions of the president than their own – particularly a sense that these groups are closed-minded or judgmental – as their reason for keeping their opinions to themselves.

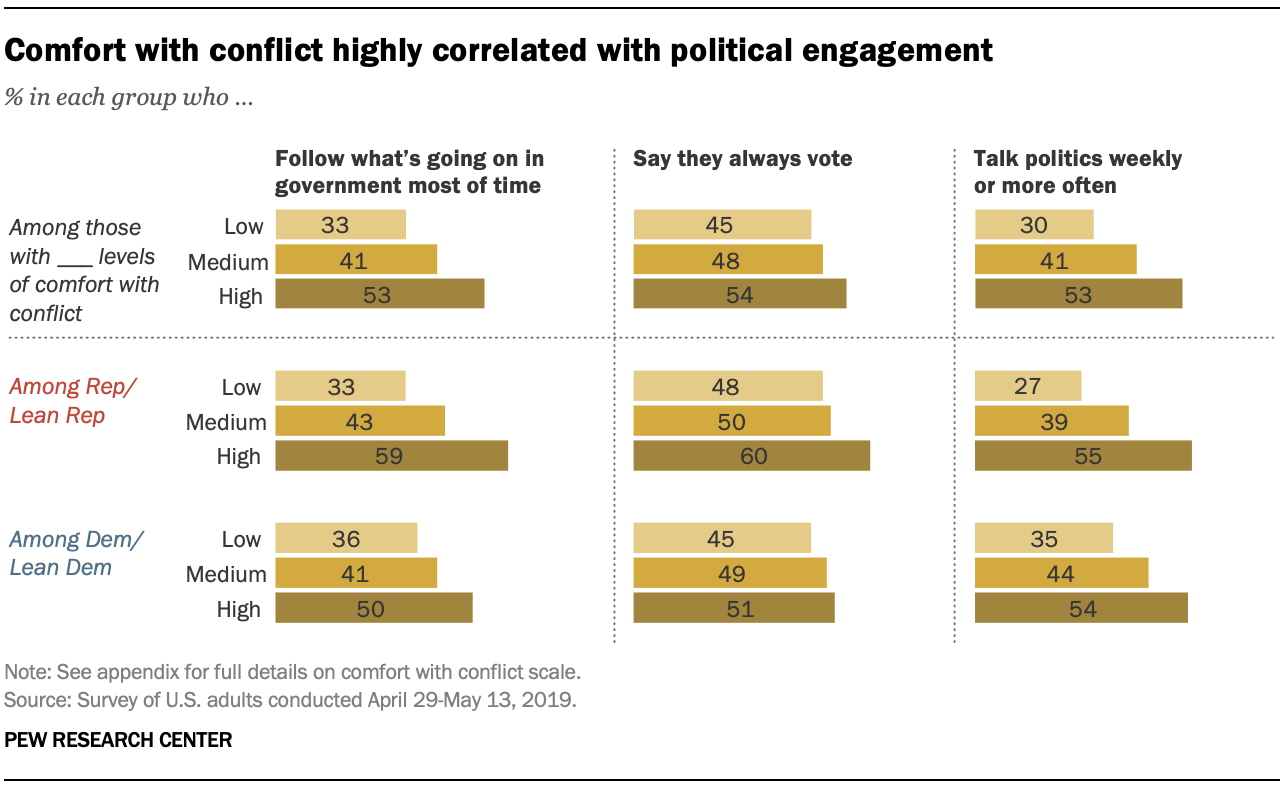

Those most comfortable with conflict more likely to be politically engaged

Comfort with conflict is associated with many attitudes about discourse and politics, including the willingness to share views of Trump in social settings. (See appendix for more details on the comfort with conflict scale.)

Those with higher levels of comfort with conflict are among the most active in politics. They are more likely than groups who are less comfortable with conflict to say they follow what’s going on in government most of the time, to say they always vote and to talk about politics frequently.

For instance, over half of Democrats and Republicans with high levels of comfort with conflict say they talk politics weekly or more often (55% and 54%, respectively). Smaller shares of those with low levels of comfort with conflict say they talk politics weekly or more.

Comfort with conflict is also predictive of some other views about political discourse. For example, Republicans and Democrats with high levels of comfort with conflict are also more comfortable talking about politics with someone they do not know well. And they are more likely to say that political conversations with those who hold opposing views are interesting and informative rather than stressful and frustrating.

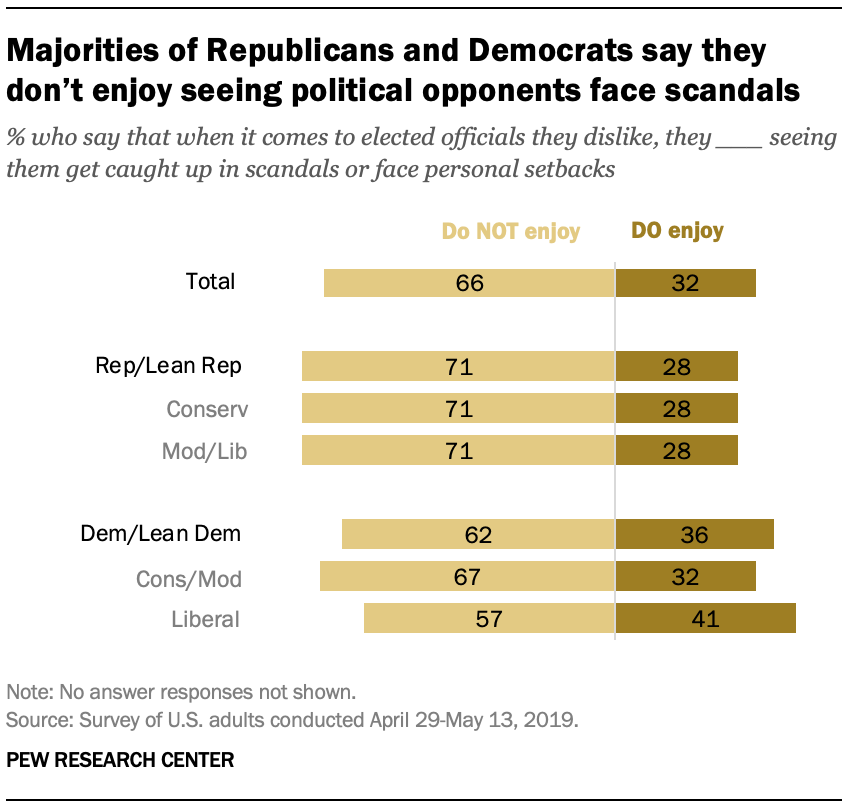

Most say they don’t enjoy seeing political opponents get caught up in scandals

About two-thirds of Americans (66%) say that they do not enjoy seeing elected officials they dislike getting caught up in scandals or facing personal setbacks, while 32% say they enjoy this.

Though

enjoyment at watching politicians they dislike face scandals is a

minority position in both parties, Democrats (36%) are somewhat more

likely than Republicans (28%) to say they enjoy this.

Though

enjoyment at watching politicians they dislike face scandals is a

minority position in both parties, Democrats (36%) are somewhat more

likely than Republicans (28%) to say they enjoy this. And among Democrats, liberals (41%) are more likely than conservative and moderate (32%) Democrats say they enjoy seeing political opponents face personal setbacks. There are no ideological differences among Republicans in these views.

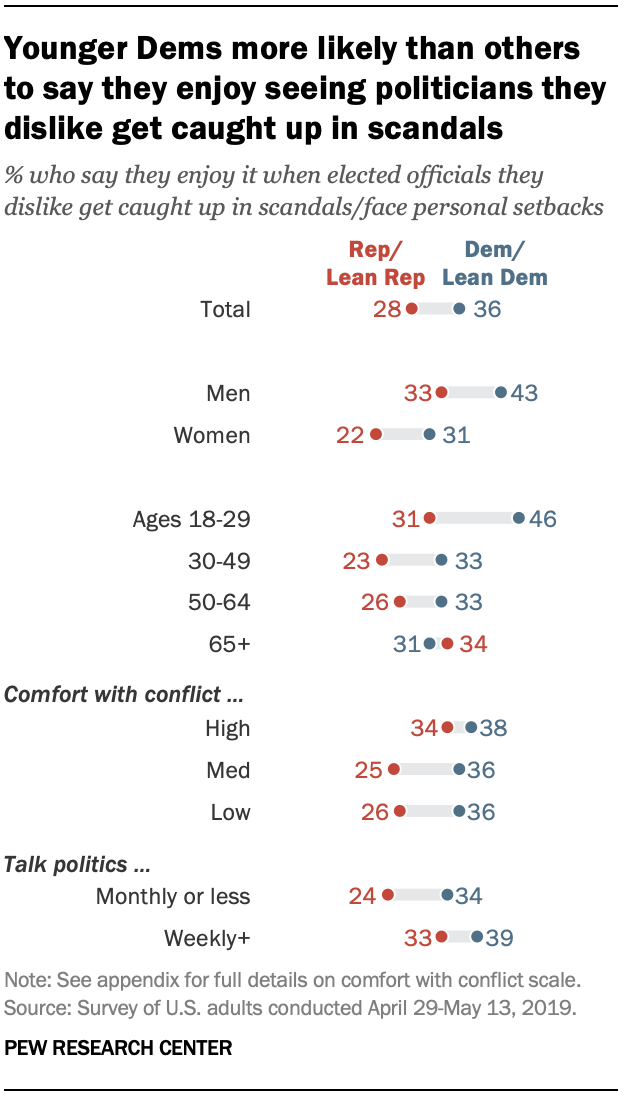

In

both parties, men are more likely than women to say they enjoy it when

elected officials they dislike face setbacks. Among Democrats, 43% of

men and 31% of women say they like it when politicians they dislike get

caught up in scandals or face setbacks; among Republicans, 33% of men

and 22% of women say the same.

In

both parties, men are more likely than women to say they enjoy it when

elected officials they dislike face setbacks. Among Democrats, 43% of

men and 31% of women say they like it when politicians they dislike get

caught up in scandals or face setbacks; among Republicans, 33% of men

and 22% of women say the same. Democrats ages 18 to 29 are especially likely to say they enjoy seeing elected officials they dislike get caught up in scandals and face personal setbacks: 46% Democrats say this, compared with about a third of Democrats in older age groups.

Republicans who express higher levels of comfort with conflict are more likely than those with lower levels of comfort to say they enjoy when opposition faces personal setbacks. Among Democrats, there are no significant differences in these views by comfort with conflict.

Within both parties, those who talk politics frequently are somewhat more likely than those who talk politics less often to enjoy seeing officials they dislike face setbacks.

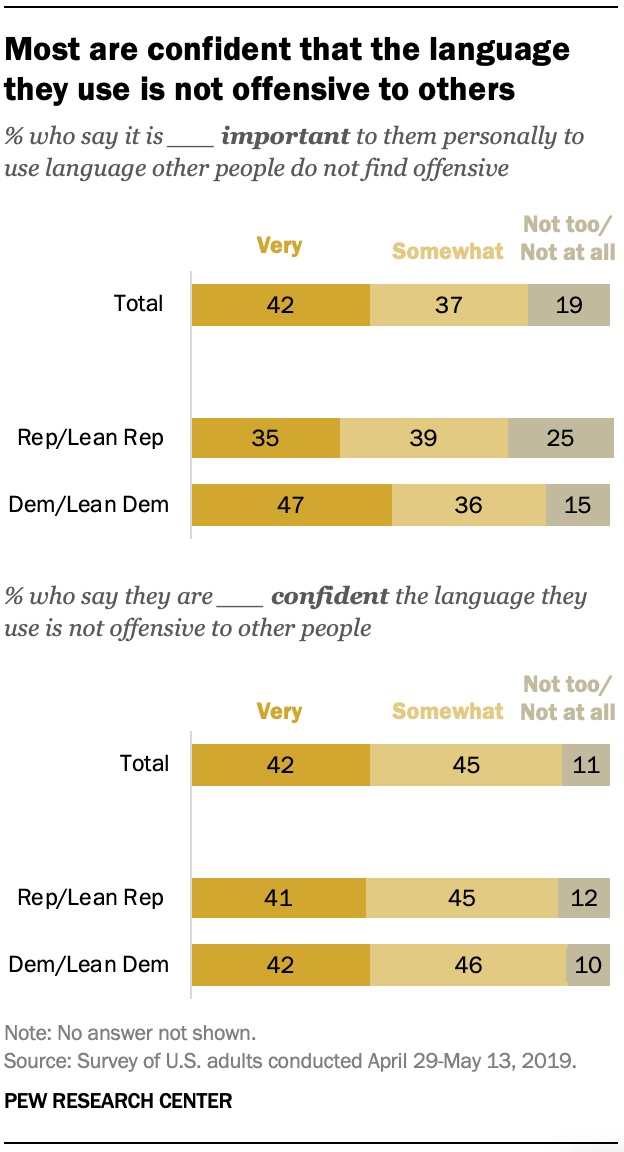

The personal side of speech and expression

A

large share of Americans say it is important to them personally to use

language that does not cause offense, and an even larger majority say

they are confident that the language they use is not offensive to other

people.

A

large share of Americans say it is important to them personally to use

language that does not cause offense, and an even larger majority say

they are confident that the language they use is not offensive to other

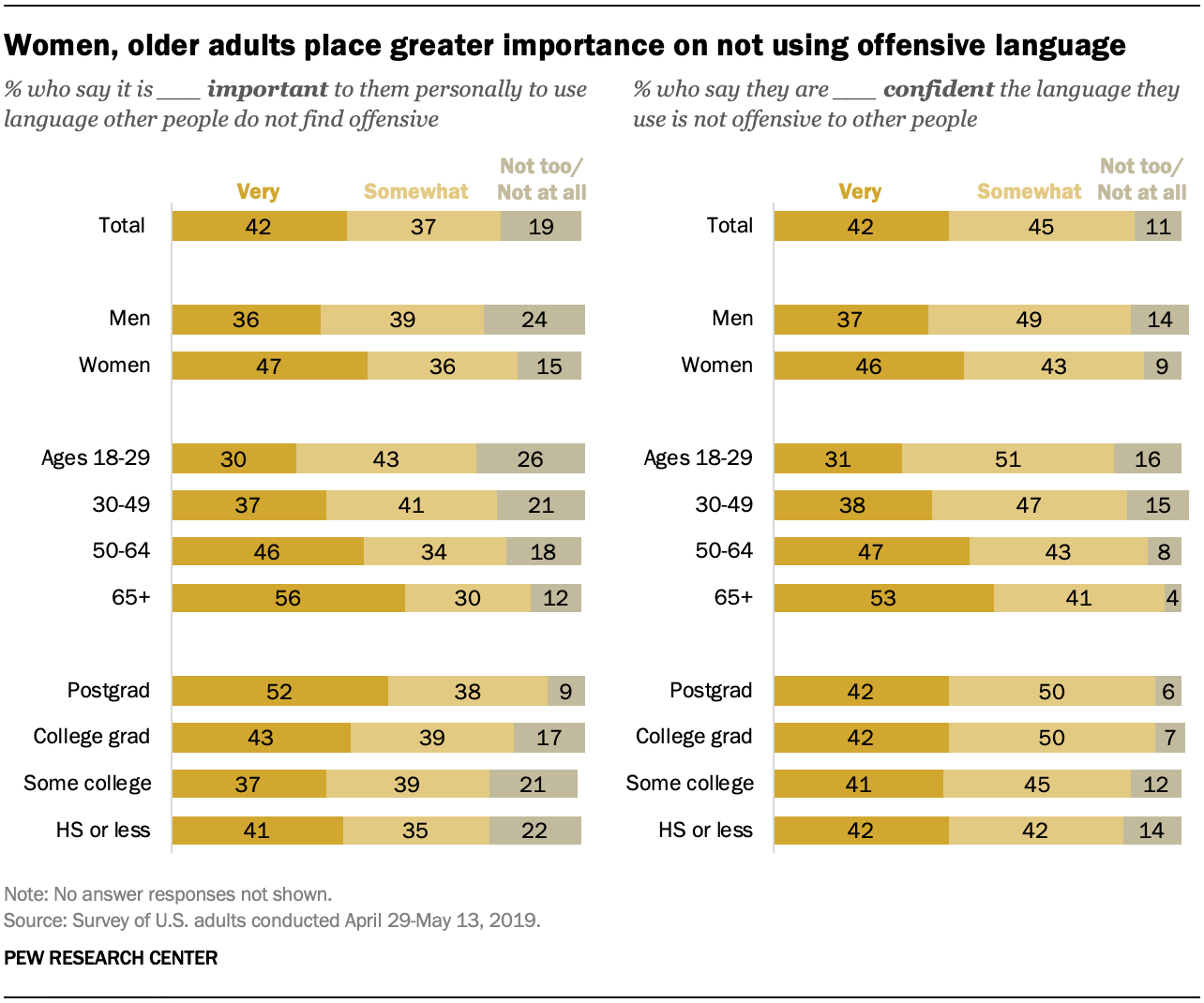

people. About eight-in-ten (79%) say it is very (42%) or somewhat (37%) important to them personally to use language that other people do not find offensive. Relatively few (19%) say this is not too or not at all important to them.

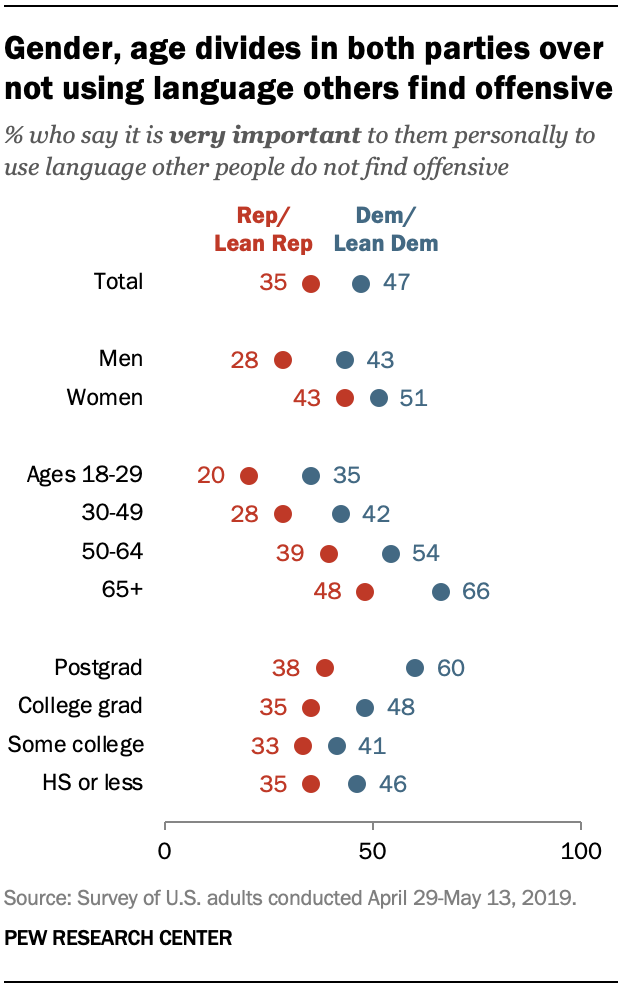

Large majorities of both Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (83%) and Republicans and Republican leaners (74%) say it is very or somewhat important that they do not use language that others find offensive. But Democrats are more likely to say this is very important (47% vs. 35%).

Americans are broadly confident that they do not use offensive language: Nearly nine-in-ten adults say they are very (42%) or somewhat (45%) confident that the language they use is not offensive to other people. Comparable majorities of Republicans and Democrats say they are at least somewhat confident that the language they use is not offensive to other people (87% and 88%, respectively).

There are notable demographic differences when it comes to views on the personal use of offensive language.

Women, older adults and those with a postgraduate degree are especially likely to place high importance on using language that is not offensive to others. Women and older adults also tend to express higher confidence that the language they use is not offensive.

Almost half of women (47%) say it is very important to them personally to not use offensive language. Slightly more than a third of men (36%) say the same. There is a similar gap between the shares of women (46%) and men (37%) who say they are very confident that their own language is not offensive.

Among

those ages 65 and older, 56% say it is very important for them

personally to not use offensive language. By contrast, just 30% of those

ages 18 to 29 say this is very important to them personally. Older

adults also are more confident than younger adults that the language

they use is not offensive to others: 53% of those 65 and older and 47%

of those 50 to 64 say they are very confident that the language they use

is not offensive; this compares with 38% of those ages 30 to 49 and

just 31% of those 18 to 29.

Among

those ages 65 and older, 56% say it is very important for them

personally to not use offensive language. By contrast, just 30% of those

ages 18 to 29 say this is very important to them personally. Older

adults also are more confident than younger adults that the language

they use is not offensive to others: 53% of those 65 and older and 47%

of those 50 to 64 say they are very confident that the language they use

is not offensive; this compares with 38% of those ages 30 to 49 and

just 31% of those 18 to 29. Higher levels of education also are associated with greater concern over not using offensive language. About half of those with a postgraduate degree (52%) say it is very important to them not to use language others find offensive, compared with 43% of those who have a college degree, 37% of those with some college experience and 41% of those who have a high school diploma or less education. There are only slight educational differences in the shares saying they are very confident that they use language that is not offensive to others.

Within

both political parties, there is a gender gap over the importance of

using inoffensive language. Republican men (28%) are significantly less

likely than Republican women (43%) to say it is very important to them

personally to use language that is not offensive. And Democratic men

(43%) prioritize this less than Democratic women (51%).

Within

both political parties, there is a gender gap over the importance of

using inoffensive language. Republican men (28%) are significantly less

likely than Republican women (43%) to say it is very important to them

personally to use language that is not offensive. And Democratic men

(43%) prioritize this less than Democratic women (51%). Younger Republicans and Democrats are both less likely than older adults in their respective parties to say it is very important to use language that other people do not find offensive. The size of the partisan gap is largely consistent across age groups, with Democrats expressing greater concern about this than Republicans.

Among Democrats, those with a postgraduate degree are significantly more likely than those with lower levels of education to say it is very important to them personally to use language other people do not find offensive. By contrast, there are no meaningful differences among Republicans by levels of educational attainment.

Have people changed how they discuss sensitive conversation topics?

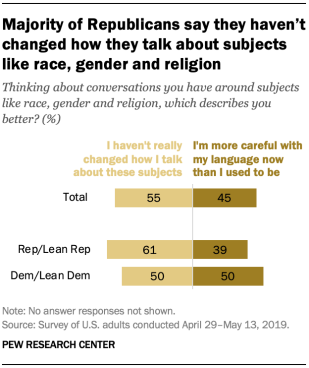

When it comes to conversations around subjects like race, gender and religion, a narrow majority (55%) say they have not really changed how they talk about these subjects, while 45% say they are more careful with the language they use now than they used to be.

On

balance, Republicans are more likely to say they have not really

changed how they talk about these subjects (61%) than to say they are

now more careful with the language they use (39%).

On

balance, Republicans are more likely to say they have not really

changed how they talk about these subjects (61%) than to say they are

now more careful with the language they use (39%). By contrast, Democrats are evenly split in their views. Half say they are more careful now than they used to be, while an identical share say they have not really changed how they talk about these subjects.

Younger adults are more likely than older adults to say they are more careful with the language they use to talk about subjects like race, gender and religion than they used to be.

Among adults ages 18 to 29, 52% say they are more careful with the language they use now, compared with 43% of adults ages 30 and older.

While there is no significant gender gap overall, Democratic men are more likely than Democratic women to say they are now more careful with the language they use when they talk about these subjects (54% vs. 46%, respectively). There are no differences between the views of Republican men and women.

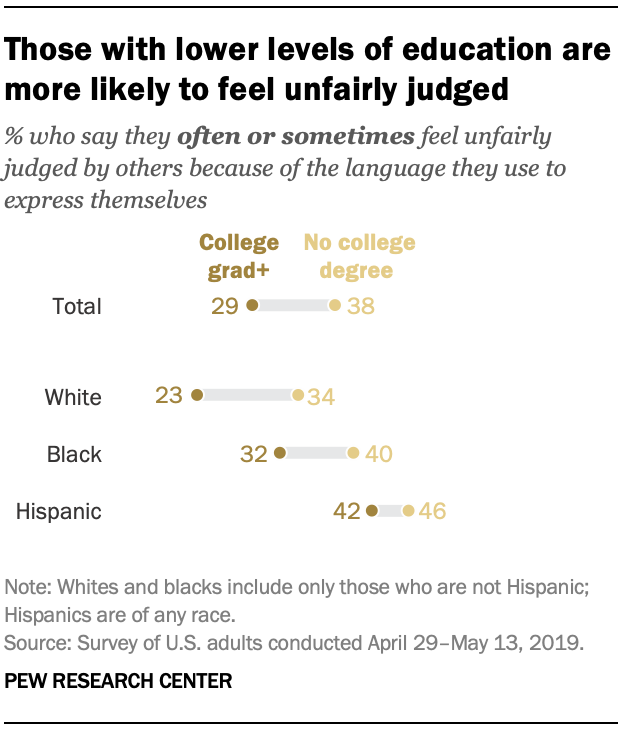

Race, education differences in feeling ‘unfairly judged’ for language use

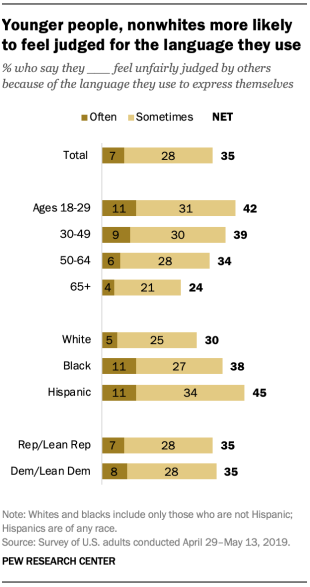

Overall,

35% of adults say they often (7%) or sometimes (28%) feel unfairly

judged by others because of the language they use to express themselves.

A larger share (64%) say they rarely (38%) or never (25%) feel unfairly

judged by others because of how they express themselves.

Overall,

35% of adults say they often (7%) or sometimes (28%) feel unfairly

judged by others because of the language they use to express themselves.

A larger share (64%) say they rarely (38%) or never (25%) feel unfairly

judged by others because of how they express themselves. While there are differences in these perceptions by age and race, there are no differences based on partisanship.

Roughly four-in-ten of those ages 18 to 29 (42%) and ages 30 to 49 (39%) say they often or sometimes feel unfairly judged by others because of the language they use to express themselves. Among those ages 50 to 64, 34% report feeling this way and just 24% of those 65 and older say they often or sometimes feel unfairly judged by others because of the language they use.

Hispanics (45%) and black people (38%) are significantly more likely than whites (30%) to say they feel unfairly judged by others because of the language they use to express themselves.

Among adults overall, those without a college degree (38%) are more likely than those who have graduated from college (29%) to say they often or sometimes feel unfairly judged by others because of the language they use to express themselves.

This

education pattern is present among both whites and blacks. Among

whites, 34% of those without a college degree say they often or

sometimes feel unfairly judged because of the language they use to

express themselves, compared with 23% of those who have graduated from

college.

This

education pattern is present among both whites and blacks. Among

whites, 34% of those without a college degree say they often or

sometimes feel unfairly judged because of the language they use to

express themselves, compared with 23% of those who have graduated from

college. Similarly, black adults without a college degree are more likely than those who have graduated from college to say they at least sometimes feel unfairly judged by others because of how they express themselves (40% vs. 32%).

There are no significant differences among Hispanics on this question by level of educational attainment.

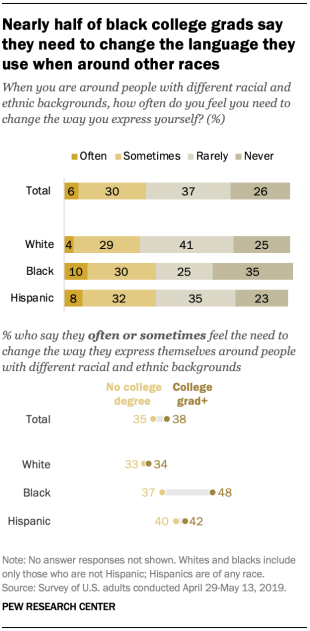

Overall,

36% of adults say that when they are around people with different

racial and ethnic backgrounds than their own, they often (6%) or

sometimes (30%) feel the need to change the way they express themselves.

A majority of the public says they rarely (37%) or never (26%) feel the

need to change how they interact with others of different racial

backgrounds.

Overall,

36% of adults say that when they are around people with different

racial and ethnic backgrounds than their own, they often (6%) or

sometimes (30%) feel the need to change the way they express themselves.

A majority of the public says they rarely (37%) or never (26%) feel the

need to change how they interact with others of different racial

backgrounds. There are significant differences in these views by race and ethnicity. Four-in-ten blacks and Hispanics say they often or sometimes feel the need to change the way they express themselves around people with different racial and ethnic backgrounds than their own; a somewhat smaller share of whites (33%) says the same.

There is little overall difference in these views by level of educational attainment. However, black adults with a college degree are significantly more likely than blacks without a college degree to say they feel the need to change the way they express themselves when they are around those with different racial backgrounds than their own (48% vs. 37%).

This education pattern among black people can also be seen in the share who say they never feel the need to change the way they express themselves around people of different racial and ethnic backgrounds. Overall, 44% of blacks with a high school diploma or less education say they never feel the need to change the way they express themselves around people of different racial and ethnic backgrounds; blacks who have some college experience but no four-year degree (32%), or who have a four-year college or postgraduate degree (20%), are much less likely to say they never have to change the way they express themselves.

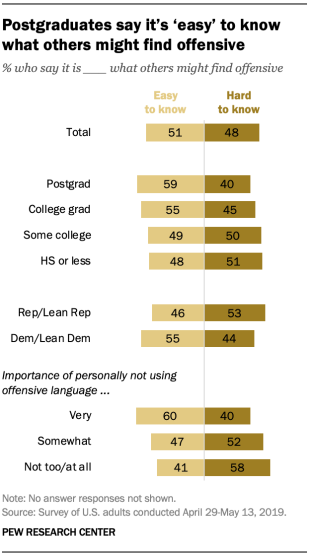

The challenge of knowing what’s offensive

Majorities of the public say there is not agreement in the country over what is considered sexist (65%) or racist (61%) language; and about half (48%) say it is hard to know what other people might find offensive.

There’s a modest partisan divide over whether it’s easy or hard to know what others might find offensive. Republicans and Republican-leaning independents are somewhat more likely to say it’s hard (53%) than easy (46%) to know what other people might find offensive. By contrast, a narrow majority of Democrats and Democratic leaners (55%) say it’s easy to know what others might find offensive; 44% say it’s hard to know.

Postgraduates

(59% to 40%) and college graduates (55% to 45%) are more likely to say

it’s easy than hard to know what other people would find offensive.

Those with some college experience or no more than a high school diploma

are about evenly divided over how easy it is to know what others find

offensive. Democrats with higher levels of education are more likely

than less-educated Democrats to say it’s easy to know what others might

find offensive. Among Republicans, there are no significant differences

in views by level of education.

Postgraduates

(59% to 40%) and college graduates (55% to 45%) are more likely to say

it’s easy than hard to know what other people would find offensive.

Those with some college experience or no more than a high school diploma

are about evenly divided over how easy it is to know what others find

offensive. Democrats with higher levels of education are more likely

than less-educated Democrats to say it’s easy to know what others might

find offensive. Among Republicans, there are no significant differences

in views by level of education. Six-in-ten of those who say it’s very important to them personally to use language that other people do not find offensive say it’s easy to know what people would be offended by. Smaller shares of those who say it’s somewhat (47%) or not too or not at all important (41%) to them personally to use inoffensive language say it’s easy to know what others find offensive.

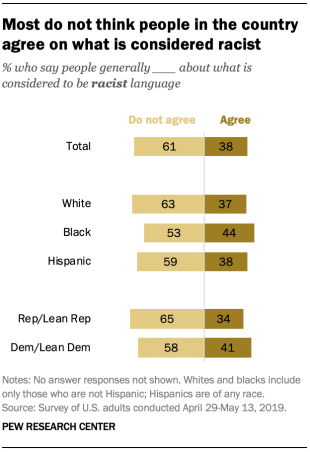

By 61% to 38%, more Americans say people generally do not agree over what is considered racist language.

By 61% to 38%, more Americans say people generally do not agree over what is considered racist language. Black people are somewhat more likely than whites and Hispanics to say people agree about what is considered racist language. Still, just 44% of blacks say that people generally agree on what is considered to be racist language, while 53% say people do not agree on this. Majorities of whites (63%) and Hispanics (59%) say people do not agree on this.

Among Republicans and Republican leaners, 65% say people generally do not agree over the definition of racist language; 58% of Democrats and Democratic leaners say the same

Similar

to views on what constitutes racist language, just 34% say people agree

on what is considered to be sexist language; a far larger share (65%)

says people do not agree about this.

Similar