The creator of the social giant’s experiment in anonymous interest groups looks back on an experiment that fell flat.

On October 13 of this year, Paul McCartney played a Pioneertown, CA roadhouse called Pappy & Harriet’s. Three hundred spectators, who paid $50 each, enjoyed a raucous bar-band version of the Macca oeuvre. For the former moptop it was undoubtedly a refreshing break from the massive nearby Desert Trip shows that seated 75,000 people, some of whom paid thousands of dollars to attend. When your audience is huge, you seek the kind of intimacy that allows you to let loose. And maybe you get in touch with the creative spark that got you to those big arenas in the first place.

Facebook, with over a billion users, is kind of an internet Beatle-mania. The stakes are massive every time it tweaks or adds to its application. No longer does the company embrace a motto of “Move fast and break things.” Speed is still good, but when you break things for a billion people, the moans echo globally. So when you are Facebook and want to try crazy stuff, you have go off-app. At least that was the thinking in 2014, when Mark Zuckerberg and company wanted to toss some digital pasta towards the ceiling to see what might stick. One glob of that spaghetti was Rooms.

Follow-Up Friday is our attempt to put the news into context. Once a week, we’ll call out a recent headline, provide an update, and explain why it matters.

Follow-Up Friday is our attempt to put the news into context. Once a week, we’ll call out a recent headline, provide an update, and explain why it matters.The brainstorm of an idealistic acqui-hire named Josh Miller, Rooms was one of a number of edgy apps coming out of Facebook Creative Labs, a launchpad for standalone products that stretched the company’s usual activities. Facebook’s VP of products Chris Cox was in charge of the Labs, acting as a kind of Professor X to the bright engineers and designers who concocted mutant products which bore the Facebook imprimatur, but lived independently from the mothership. Users would download these apps and interact with them separately from the main application (though these products would leverage one’s Facebook identity). The most heralded was probably Paper, which was a cleverly designed alternative way of viewing News Feed. The least loved was Slingshot, which was inspired (some might use a stronger word) by Snapchat’s ephemeral messaging concept.

And then there was Rooms. It was borne from a meeting Miller had with Zuckerberg soon after the former’s arrival in January 2014, via an acquisition of Branch, which was like a conversational Twitter. Like a Beatles lover who came of age after the band broke up, Miller had been intoxicated with the early internet and web—when cyberspace felt like a place, with numerous eddies like The WELL or Usenet where strangers could share their interests and issues with those of similar mien. He had heard that Zuckerberg shared some of the same feelings, and might want to build a product that captured the spirit and utility of those forums. “He talked about how Facebook is really great for connecting you to friends and the people you love,” says Miller. “But there’s a whole lot of other interests that people may have, where they want to connect with people they might not know.” Zuckerberg encouraged Miller to see if he and a team could answer the question, “Is there room for a place where you can connect to people you don’t know, who can expose you to new topics and things you care about?” And they would do it in the mobile world.

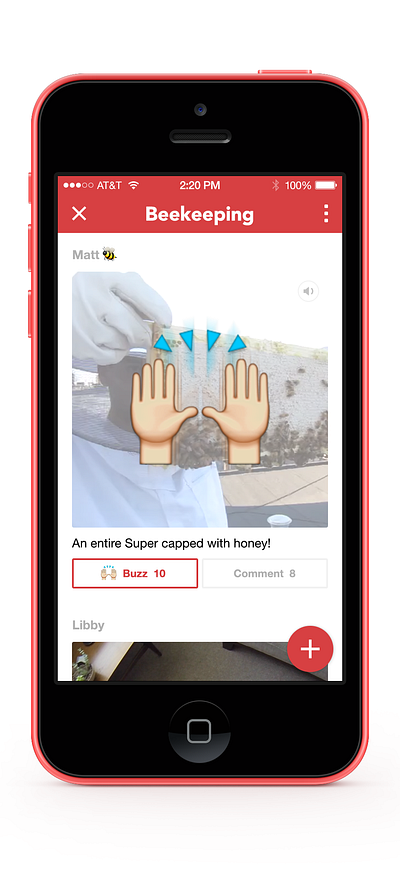

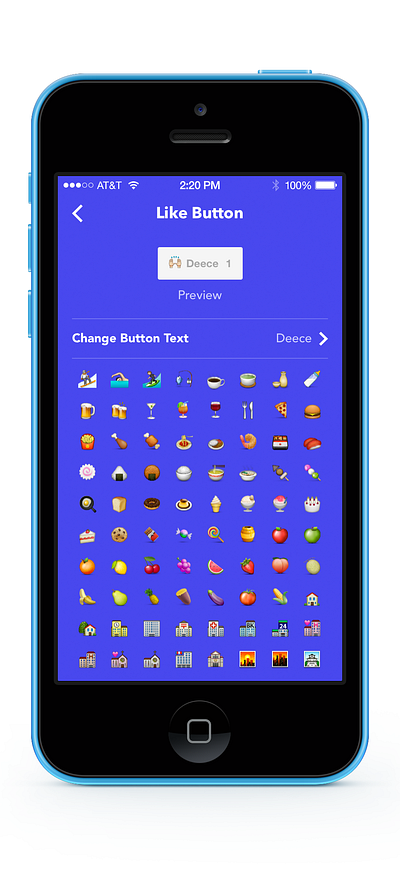

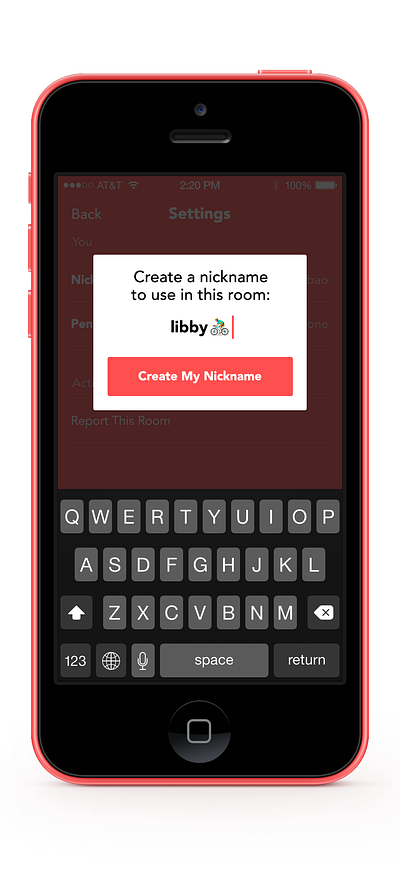

Rooms, released on the iOS platform about seven months after that conversation, indeed distinguished itself from its owner’s main business. It allowed users to easily set up a “room” to share information or feelings about a topic; most often, because of the app’s mobile focus, that sharing would happen via photo or video. Cool enough. But because it was launched with the freedom of a Pappy & Harriet’s booking, Rooms could engage in a number of heresies. Creators of a room set their own ground rules for behavior. Visitors left their identity at the door of the room, and could not even transport their in-room personas to another room — thus one’s expressions were freed from the burden of varnishing one’s self-presentation. “We’re not building a social network,” Miller told me upon launch. Because it discarded so many principles of its billion-user parent, I called it a “Bizarro Facebook” in a piece I wrote at launch.

Rooms was also distinctive for an intriguing innovation: the way one discovered and joined a room. This was done via visual invitation: an image with a secret code embedded that you could download or scan with your camera. (You could even print it in a book and have people take a picture of it to gain entry to the room.) Miller now says that Zuckerberg, though charmed with the idea, warned that its novelty might present potential users with friction, which could discourage participation. “Josh, you’re very creative,” he recalls Zuckerberg saying. “But some of the most innovative and impactful products really aren’t that new — you don’t have to reinvent the wheel.” Zuckerberg did not offer his advice as proscriptive, however, and allowed Miller to make the call.

The Rooms interface. (via Facebook)

The Rooms interface. (via Facebook)Rooms garnered attention, and won over some adherents. One of the most successful rooms was devoted to depression and mental health: over 5,000 people actively participated in frank and lively exchanges. It led Miller to feel he was onto something. “If you suffer from depression, you don’t post about it on Facebook or post on Instagram,” he says. “You want answers from people who have dealt with it, but the people who can answer questions aren’t the ones you know.”

But over a period of months, the product did not build to the scale that could possibly make it significant to Facebook. “A few thousand people in a room is nothing,” Miller admits. “The number you need is a lot.” Miller won’t talk about how many people downloaded the app, or how many rooms they created. “We were less concerned about the total number, and more about how many healthy communities there were.”

Growth was flagging when the burgeoning tech team in the White House lured Miller to join as its first director of product management in September 2015. By that time, Miller understood that Rooms was in its final days, and heard in October that the Rooms would no longer be serviced. “I totally understand why it didn’t make sense for Facebook,” says Miller. “I think a lot of things that hindered our growth were mistakes that I personally made.”

The formal end came on December 7, 2015, when Facebook not only killed off Rooms, but also ended Creative Labs. (Facebook itself declined to participate in this article. Post mortems aren’t its thing.)

So why didn’t Rooms work? “There wasn’t one thing,” says Miller, who is still at the White House, loving his stint among Obama’s techies. He admits to mistakes in focus and execution. “If we knew that support communities were going to be big, we would have designed Rooms completely differently. We designed an app that was good for photos and videos, and didn’t have search.” The inability to actually find which rooms were available was a particularly misguided choice, made because Miller and his team believed that active forums on the early internet owed at least part of their success to the difficulty in finding them. Once you figured out how to get there, this suspect logic went, the place would be special to you. “That was over-intellectualizing,” Miller now says.

He also now sees that the nifty scan-and-enter-new-room feature was, as Zuckerberg predicted, something that inhibited growth.

Funny about that: The feature was just ahead of its time. “A lot of people gave us flak for that — they said, ‘Why would you ever take a picture of a code?’” recalls Miller. “But six months after we appeared, the way you added friends on Snapchat was exactly that. And a year later, when you add a friend on Facebook’s Messenger, it’s with a code as well. It’s kind of the default to add people.”

Miller is anything but remorseful — Rooms was a great experience for him, and he particularly cherished the interaction with and encouragement of his bosses. “I think it’s cool in the first place that Mark and Chris would say, ‘You know what? This has nothing to do with Facebook, but we think it would be good for the world, and good for society if we had a place we could meet strangers and talk about the things that interest you. Even if you don’t know the people, let’s invest in it. Even though we’re not even sure how this could fit or where it would go.’”

In fact, Miller still thinks there is an opportunity for someone to fulfill his original impulse: creating a special, safe space where people of shared interests could virtually gather, regardless of how many degrees separated them otherwise. “It takes more patience,” he says. “I think it’s crazy that we have this technology that lets us connect to anybody around the world instantly, and we only talk to people that we know.”

אין תגובות:

הוסף רשומת תגובה