American political parties have long been vehicles to represent ever-shifting coalitions

of particular interests — economic, regional, social and ideological.

For example, Great Plains farmers who often voted Democratic a century

ago now solidly favor Republicans; African Americans who were loyal GOP

voters for decades after the Civil War began shifting during the New

Deal and now are overwhelmingly Democratic. Political observers can

still spend hours of pre-election time ruminating over whether the

“big-city ethnic vote” or the “farm vote” will prevail.

American political parties have long been vehicles to represent ever-shifting coalitions

of particular interests — economic, regional, social and ideological.

For example, Great Plains farmers who often voted Democratic a century

ago now solidly favor Republicans; African Americans who were loyal GOP

voters for decades after the Civil War began shifting during the New

Deal and now are overwhelmingly Democratic. Political observers can

still spend hours of pre-election time ruminating over whether the

“big-city ethnic vote” or the “farm vote” will prevail. But the parties also are coalitions of distinct groups of voters, whose shared attitudes and values unite them — and shape the parties they incline toward — at least as much as more impersonal economic and societal forces. The Pew Research Center’s mammoth new political typology report offers a different way to think of the two major parties’ component pieces. (For the purposes of this post, we limited our analysis to registered voters and combined self-identified Republicans or Democrats with independents who lean toward one or the other party.)

Who are the political typology groups?

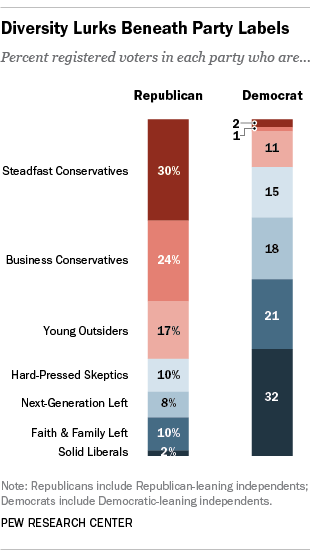

For both parties, two similar but distinct groups form their electoral cores, with a younger, more ideologically mixed group providing crucial — but not always consistent — support. First, let’s look at the left.

Nearly a third (32%) of Democrats are what we call Solid Liberals, while about a fifth (21%) are part of what we call the Faith and Family Left — a somewhat more socially conservative group than Solid Liberals. Add in the younger, more economically moderate Next Generation Left (18%) and you have seven out of 10 Americans who identify with or incline toward the Democrats.

On the right, three-in-ten Republicans are what we term Steadfast Conservatives and nearly a quarter (24%) are Business Conservatives — just as opposed to government taxes and regulation, but more moderate on social issues and friendlier toward business interests. Another 17% are Young Outsiders — fiscally conservative but socially quite liberal. Interestingly, those three groups comprise 71% of Republican registered voters — the same share accounted for by the three biggest Democratic components.

Democrats and their leaners make up almost half (48%) of registered voters, while Republicans and their leaners account for about 43%. The remaining 9-10% are people who expressed no preference for and did not lean toward either major party. As you might expect, they’re the most varied segment of the electorate, with none of our typological groups predominating.

Looked at this way, it’s clear that neither party can depend solely on its largest, most ardent (and often loudest) supporters to win elections. For example, Steadfast and Business Conservatives together make up 54% of all Republicans and Republican leaners, but only 27% of registered voters; similarly, 53% of Democrats and Democratic leaners, but only a third of registered voters, are Solid Liberals or Faith and Family Left.

Not only that, but there are key differences even between the core groups in each party. Business Conservatives, for instance, are significantly more supportive of a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants and more supportive of homosexuality than their Steadfast allies; they also are more favorable toward free trade agreements, an active U.S. role in world affairs and, as their name implies, business interests generally. (The current battle over reauthorizing the Export-Import Bank reflects, in part, that divide.)

Meanwhile, the Faith and Family Left is much less supportive of same-sex marriage than are Solid Liberals, and are more favorably inclined toward U.S. efforts to solve global problems.

|

| Rubén Weinsteiner |

Rubén Weinsteiner

אין תגובות:

הוסף רשומת תגובה